Читать книгу I Saw Water - Ithell Colquhoun - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

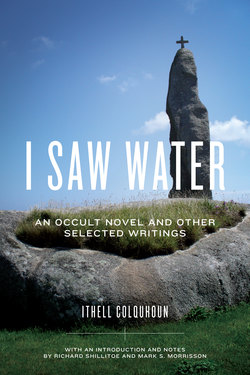

The centerpiece of this book is the previously unpublished novel I Saw Water. Written by the author and artist Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988), it is set on the island of Ménec, where Sister Brigid inhabits the Ianua Vitae Convent. She is an unconventional nun, but it is soon revealed that the convent itself has an unconventional mission. It belongs to the Parthenogenesist Order, ostensibly Roman Catholic, but whose purpose is more reminiscent of certain schools of alchemy than of Catholicism. Its aim is the unification of the separated genders, the achievement of which will signal the transmutation of fallen, sinful humanity to a state of spiritual perfection, restore nature’s equilibrium, and confirm the unity of the hermetic cosmos. In tandem with this alchemical undercurrent, many aspects of conventual and ritual life on Ménec have more in common with pagan nature worship than with Christianity. Ménec itself is an unusual island. It is the Island of the Dead, and all the inhabitants, nuns and laity alike, have died and are now in transit, working their way toward their second death. The concept of the second death presented in this novel differs from that of Judeo-Christian eschatology. It has no place in Catholic theology, being more associated with Eastern spiritualities that would have likely reached Colquhoun through the teachings of the Theosophical Society.

Sister Brigid’s cousin, Charlotte, is also on the island, having just taken her own life. Before her suicide, she was the mistreated wife of a homosexual husband. Despite the personal vulnerabilities that she carries with her, she is as much a spiritual guide to Brigid as are the convent mistresses. Another influence on Brigid is a local landowner and heir named Nikolaz, who bears strong similarities to Adonis, the mythological vegetation god. He entices Brigid from the convent but dies by drowning (inevitably, as it will come to be understood) before they can leave the island together. Nonetheless, eventually Sister Brigid is able to cast off her personality and human emotions and achieve a state of disembodied peace. I Saw Water is narrated in a matter-of-fact style that recounts as commonplace a remarkable series of events, including an encounter with a subhuman baboon girl, rituals dedicated to sacred wells, a pagan snake dance, the circulation of a powerful heirloom, the touch of an ectoplasmic hand, and even a demonstration of the power of bilocation by the convent’s novice mistress. Naturalistic passages are juxtaposed with lengthy sequences derived from dreams, resulting in dislocations of time, place, and logic.

As this brief summary shows, the novel is not mainstream fiction. It is forgivable that in the mid 1960s, when it was written, no publisher felt confident enough to add it to their list, especially as Colquhoun required that each chapter be printed on color-coded paper to evoke its occult structure. Today, with more widespread knowledge of the spiritual traditions of East and West, deeper appreciation of dreams and their imagery, and greater awareness of the importance of the occult in modernism, some of the surface strangeness has mellowed. Even so, there is still much to challenge the nonspecialist reader. One purpose of our introduction and notes is to explain concepts and terms that occur within the novel and might be unfamiliar. Another is to suggest important lines of analysis.

Although Colquhoun is well known to two groups of people—those interested in the history of surrealism in England in the years leading up to World War II and those interested in ceremonial magic in the mid-twentieth century—outside of these groups (neither of which is extensive) she remains almost entirely unknown. Much of her written work is unpublished or appeared in “little” magazines that can be difficult to access. Similarly, her artwork is largely in private ownership or stored in archives and is rarely seen in public. So, in order to place the novel in the context of her work and to show how it fits within wider historical influences, we have included a small but representative sample of her images and other writings. Through this book we hope to bring her extraordinary work into wider knowledge and appreciation.

BIOGRAPHY

Margaret Ithell Colquhoun was born to British parents in Assam, India, where her father held a senior position in the Indian Civil Service. She was brought to England as a young child, the family eventually settling in Cheltenham. There she attended a well-known private school, Cheltenham Ladies College, and the local college of art, and then moved to London in October 1927 to study at the Slade School of Art, at that time the foremost art school in England. The Slade had been instrumental in the nascence of modern art in pre-WWI London. It had taught such painters as Augustus John—known for his espousal of postimpressionism—and a younger generation that included Mark Gertler, Christopher Nevinson, and Paul Nash. The important Bloomsbury painters Duncan Grant and Dora Carrington enrolled at the Slade, as did the vorticist artists Wyndham Lewis, Edward Wadsworth, and David Bomberg, who published their anti-Bloomsbury and anti-Victorian little magazine Blast just a month before the outbreak of war. Colquhoun entered the Slade during the interwar period, only a few years after Eileen Agar had left it for Paris. As a measure of her skill and potential, Colquhoun shared the school’s prestigious Summer Composition Prize in 1929. She graduated at a time when, as it had been shortly before World War I, British art was being revitalized by its engagement with continental art movements, to which it had initially been slow to respond.

In the 1930s, the intellectual and artistic movement that left the greatest mark on the British scene was surrealism. Its watershed event in London was the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries. From June 11 to July 4, 1936, it attracted some one thousand spectators per day. The exhibition featured works by the major continental surrealists, supplemented by a program of talks and readings. Colquhoun attended a lecture by Salvador Dalí, during which, while bolted into a deep-sea diving suit, he very nearly suffocated. The poet and essayist André Breton, the movement’s leading figure, spoke to a crowded house. A young Dylan Thomas wandered about the gallery serving cups of boiled string.

Colquhoun was drawn to surrealism by the work of visual artists such as Dalí, but more importantly by the writings of Breton. Breton elaborated a theoretical framework for surrealism in which automatism, poetry, psychoanalytic theory, trances, and the study of dreams were used to challenge accepted notions of reality. Believing that the contradictions between apparent opposites such as the conscious and the unconscious, or dream and wakeful thought, could be resolved by such methods, surrealism aimed at a higher reality. As Breton had put it in 1924, “I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.”1

The appeal of such ideas for Colquhoun is not hard to fathom. During her youth, she had developed a lasting interest in magic, acquiring a wide range and depth of occult knowledge. This was ably demonstrated by her first publication, an article entitled “The Prose of Alchemy,” which was written while she was still a student and published in 1930 in G. R. S. Mead’s influential journal of Gnosticism and esotericism, The Quest.2 Mead had been part of Theosophical Society founder H. P. Blavatsky’s inner circle in the 1880s, even editing the key theosophical publication Lucifer with Annie Besant after Blavatsky’s death. But internal scandals that tore rifts in the Theosophical Society led Mead to resign from it in 1909. He then founded the Quest Society, whose lectures at Kensington Town Hall were attended by, among others, W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, T. E. Hulme, Martin Buber, Jessie Weston (author of From Ritual to Romance, a major influence on T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land), and the young Ithell Colquhoun. Mead published works by several of these authors in The Quest. So, while many of Colquhoun’s subsequent publications would appear in journals tied to surrealism, she was equally engaged in the circles and journals of occult London.

To the continental surrealists, the link between the surreal and the hermetic was clear and uncontentious. In the Second Surrealist Manifesto (1929), Breton made the bond between alchemy and surrealism explicit.3 His “union of opposites” would have been a familiar idea to a woman steeped in alchemy; indeed, an important alchemical motto is conjunctio oppositorum (the conjunction of opposites).4 The impact of occult ideas and alchemical imagery on the work of visual artists associated with surrealism has long been recognized, and recent scholarship, such as the work of Urszula Szulakowska (2011) and Camelia Darie (2012), continually redraws and extends these boundaries.5

In England, however, the situation was very different. When, in 1940, Colquhoun refused to curtail her magical activities, she was expelled from the London surrealist group. The group’s leader, E. L. T. Mesens, undoubtedly had a strong and unwavering personal mistrust of the occult. His motives, however, may have been mixed: it is said that his antipathy to Colquhoun was heightened by a powerful sexual jealousy.6 The consequences for Colquhoun were profound. On the cover of the June 15, 1939, issue of the London Bulletin, one of the most progressive British art publications of its day, she had shared the bill with such figures as René Magritte, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, and the Marquis de Sade.7 Her photograph had been taken by Man Ray (fig. 1).8 She had recently visited Breton in Paris, exchanging horoscopes with him (both had Neptune in the House of Death), before spending time in Chemillieu with a number of other artists engaged in reevaluating the role of automatism in surrealist painting. To all appearances, her star was rising. In fact, it had reached its zenith. World War II was about to change the intellectual climate of Europe and the United Kingdom. Surrealism, whose promise of intellectual and personal freedom had clearly failed, became the voice of the discredited past. Colquhoun’s exclusion from the London group, the bitterness surrounding her disastrous and short-lived marriage to surrealist artist and writer Toni del Renzio, her failure to find a publisher for her alchemical novel Goose of Hermogenes, and two commercially unsuccessful shows at the prestigious Mayor Gallery in Mayfair all made the 1940s a testing decade for her.

Colquhoun spent increasing periods of time away from London, in Cornwall, moving there permanently in 1956. For the last three decades of her life, she lived in a village near Penzance on the Land’s End peninsula. Eventually, in physical isolation from the London-based art world and the capital’s magical societies, she achieved a measure of recognition, more from her writing than from her painting. Goose of Hermogenes finally appeared in print in 1961, following the publication of Colquhoun’s idiosyncratic and highly imaginative travel books on Ireland and Cornwall.9 It was here in Cornwall, with its rich traditions of myth and folklore, as well as its profusion of prehistoric monuments, that she spent much of her time developing and diversifying her occult knowledge and skills. Her final prose book, Sword of Wisdom,10 remains the authoritative account of MacGregor Mathers, a key figure in late nineteenth-century magic and a founder of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a society whose teachings and rituals are still influential today. It was also in Cornwall that Colquhoun wrote I Saw Water.

THE SPIRITUAL FRAMEWORK OF I SAW WATER

In this book, we use the words “occult,” “magical,” “hermetic,” and “esoteric” to indicate aspects of a worldview that has its roots in antiquity and which, in today’s world, offers a description of the universe that differs markedly from those proposed by materialist sciences and monotheistic religions. It numbers among its diverse sources Egyptian and Greek mystery texts, as well as writings by pre-Socratic philosophers, Gnostics, and medieval Jewish mystics. It is sufficiently flexible to incorporate aspects of Eastern religion within a generally Christian framework. It includes the practical arts of alchemy, divination, and the casting of spells. It frequently claims that all things are related through a series of correspondences and regards the cosmos not only as living but as perpetually regenerating and reconstituting itself.11 As a serious explanation of how the universe works, occultism suffered major reversals at the hands of the Enlightenment but never received a knockout blow. In fact, Colquhoun came of age when Britain, Western Europe, and the United States were experiencing a decades-long resurgence of interest in magic that has loosely been styled the “occult revival.” As a result of spiritualist séances, magical orders (such as the Golden Dawn), explorations of Eastern and Western esoteric traditions by the Theosophical Society, alchemical experiments, and a broad popular interest in subjects ranging from poltergeists to the Gothic, Britain witnessed a proliferation of print culture (books, periodicals, posters, and artwork) and what might now be termed “new religious movements.” These offered alternative spiritualities, together with social and cultural opportunities for participation.

Colquhoun herself was as completely at home with the Qabalah, the system of magical study derived from medieval Jewish mysticism,12 as she was with Eastern traditions such as Tantra. She would, in her maturity, be drawn to contemporary developments such as Wicca, neo-Druidism, and Goddess religions. At various times in her adult life, she was a member of two Golden Dawn–inspired organizations (the Ordo Templi Orientis and the Order of the Pyramid and the Sphinx), the somewhat similar Order of the Keltic Cross, several Co-Masonic lodges, English and French Druidical orders, the Theosophical Society of England, and the Fellowship of Isis, this last being an association dedicated to honoring the divine mother Goddess.

As a magician, then, Colquhoun adopted a highly syncretic approach. That is, she valued diversity and attempted to make a harmonious whole out of fragments taken from different spiritual traditions, each of which, she believed, contained hidden aspects of the greater truth.13 Among these influences, Colquhoun’s roots in her own Christian background remain readily apparent. Hers, however, was a heterodox Christianity. Her lasting interest, for example, in the loss of androgyny that allegedly occurred at the Fall, and the consequent need for gender reintegration, places her much closer to the ideas of mystical thinkers such as Jacob Böhme, Emanuel Swedenborg, and William Blake than to conventional Christian doctrines.

In keeping with Colquhoun’s personal spiritual landscape, I Saw Water is a syncretic novel: within its pages ceremonial magic, alchemy, pagan nature worship, and theosophical teachings all happily rub shoulders with Roman Catholicism. In fact, as was the case with Colquhoun’s earlier novel Goose of Hermogenes, the hermetic is embedded in the novel’s structure. In Goose of Hermogenes, progress through the chapters reflected the heroine’s progress through the stages of alchemical transformation. In I Saw Water, Colquhoun originally intended to represent the heroine’s spiritual advancement by ascending, chapter by chapter, through the sephiroth of the Qabalistic Tree of Life, from Malkuth in chapter 1 to Kether in the final chapter. Her notes show that she also considered associating the chapters with a Christian journey: progression along the Stations of the Cross or the Mysteries of the Rosary. In the final scheme, however, she rejected both the Qabalistic and the Christian paths, choosing instead to name each chapter after one or another of the geomantic figures.

Geomancy is a traditional technique of divination believed to have originated in the Middle East at some uncertain time in the past. It achieved some popularity in the twentieth century thanks largely to its advocacy by Golden Dawn–influenced magicians, but never to the extent achieved by another divinatory technique: Tarot readings. In geomancy, the inquirer generally makes a series of marks upon a sheet of paper, renouncing all conscious control. The resulting pattern is then classified according to a formula to produce one of a number of standard figures. Each of the geomantic figures is known by a Latin name and has a range of meanings, derived in part from its planetary and zodiacal associations.14 So, for example, the figure Laetitia, which Colquhoun translates as “Joy,” governs chapter 13 and signifies progression and happiness. For the chapter in which the heroine finally achieves complete separation from all her earthbound concerns, its relevance is clear.

Colquhoun’s adoption of the geomantic figures was a late decision, made after the basic structure of the novel had been determined. According to Israel Regardie, geomancy and other methods of divination are not used primarily to predict what is to come. Instead, they are used to facilitate the expression and growth of inner psychospiritual abilities by placing practitioners in contact with internal or external forces of which they are unaware.15 Colquhoun uses the figures, therefore, not to prefigure what might lie ahead, but as a commentary on the psychological state of her characters, their development, and their circumstances.

Despite these structural changes, the idea of a journey remains central to the novel, as all the characters are progressing, in their individual ways, toward their second death. The second death is a construct popularized in the West by the teachings of the Theosophical Society. Members of the society draw distinctions between a person’s physical body, their astral body, their mental body, and the immortal soul. There is no such thing as the finality of death as it is ordinarily understood; death is merely the laying aside of the physical body. The emotions and passions generated during life on earth continue to live on in the astral body until, with time, they become exhausted and fade away. When this process has finished, the second death takes place, but the soul survives and will later occupy another physical body. Over the course of many such cycles of reincarnation, the soul evolves until, ultimately, it dispenses with material phases altogether, existing only in a world of thought-forms.16

Sister Brigid, Charlotte, Dr. Wiseacre, Roli, and the novel’s other characters are in a dynamic state of disequilibrium and do not necessarily understand what is happening (some readers may share the feeling). This is because, although they are physically dead, their personalities are still active in the astral body and they continue to see, hear, think, and feel. But gradually the fact that physical death has occurred becomes inescapable. It is then that the second death can occur. This is the journey that the heroine makes during the course of I Saw Water. Arriving at Ménec as Ella de Maine, she becomes Sister Brigid for the duration of her stay at the convent. Once she has moved beyond the convent, she finally loses all sense of personal identity. Name and personality are attributes that, along with her possessions, she casts aside: “Everything is free and I am free of everything,” she says in her culminating insight (page 134).

THE PHYSICAL SETTING OF I SAW WATER

The place where people live their lives influences the nature of the lives they lead. In turn, those lives leave their mark upon the place. This is as true of inner, spiritual lives as it is of outer, practical ones. Religious beliefs and activities have a reciprocal interaction with the locality. Beliefs may be inspired or strengthened by natural features, and, conversely, beliefs and observances leave their imprint on the landscape—for instance, in the placement of devotional buildings and funerary monuments. As beliefs change over time, their history may be read in the archaeological record and in place names. There can be few places in Europe that demonstrate this more convincingly than Brittany, where the events in I Saw Water take place.17

Brittany is a region of northwestern France. It is a peninsula, jutting out from the mainland into the Atlantic Ocean. Its remoteness has led to cultural as well as physical isolation. Brittany has, for example, retained its own language, folklore, and musical traditions. Archaeologically, it is a highly ritualized landscape, containing prehistoric stone circles, megalithic tombs, and stone avenues in abundance. It was Christianized by missionaries from Wales in the sixth century and still possesses a rich diversity of saints and religious communities. Christian worship has left its physical mark in the erection of churches and the adaptation of pagan tombs. The Pardon—the celebration of a saint’s feast day, involving a procession, Mass, and feasting—is a uniquely Breton carnival.

For I Saw Water, Colquhoun drew heavily upon her personal knowledge of Brittany—its places, customs, and festivals. At the time when she was writing her novel, she was an active member of the British Druid Order. As a fellow Druid visiting from Cornwall, she was able to take part in the rites of a Breton Gorsedd (a large gathering devoted to spiritual, poetic, and musical celebrations) and attend at least one religious pardon in 1961.

Many of the place names in the novel are authentic locations in Brittany, although Colquhoun often adapts them for her own purposes. The novel is set on the island of Ménec, which Colquhoun identifies with the Island of the Dead. In reality, Ménec is not an island but the mainland site of vast prehistoric avenues of standing stones (fig. 2). Although the purpose of these enigmatic stone rows is largely obscure, their connection with Neolithic funeral rituals and beliefs is not in doubt. They, and many dolmens, are orientated according to astronomical events concerning the movements of the sun and moon. One of the most extensive of these alignments, containing more than one thousand stones and extending over four thousand feet in length, is known locally as the House of the Dead. In light of this, Colquhoun’s poetic identification of Ménec with the Island of the Dead is easily understood. Similarly, Cruz-Moquen, the name Colquhoun gives to a neighboring island, in reality is not an island either, but the site of a prehistoric dolmen that has been Christianized by the erection of a Calvary cross on top of its capstone (fig. 3). By adopting and adapting these locations, Colquhoun is indicating that they are sacred spaces of lasting spiritual significance. She locates the novel’s action in places that have been associated with worship, death, and rebirth since prehistory. Religious beliefs and ceremonies may change with the passage of time—pagan, Catholic, or neo-Druidic—but the sequence of changing observances over millennia provides a sense of continuity and natural order. More than that, because of their astronomical alignments, these places are tied to solar and lunar rhythms that predate and will outlast human presence.

From the outset, Colquhoun is at pains to emphasize the rhythms of nature. Sister Brigid, whose very name recalls the Celtic triple goddess, devotes her time to seasonal pastoral activities and to animal husbandry. References to holy wells, tree lore, herbal remedies, and the celebration of the equinoxes establish connections between nature, an ancient past, and present-day Druidic revivals. Worship at the Ianua Vitae Convent, although Roman Catholic, contains many pre-Christian, pagan elements. Vestiges of the ancient religion of the Celts are everywhere, in the land, the place names, and the monuments.

Colquhoun’s choice of personal names reflects Breton history. Several of the characters, such as Sister Gildas, are named after historical figures, frequently saints, who have connections with Brittany. Colquhoun chose names with one eye to the saint’s feast day in the Breton religious calendar and the other to the internal chronology of the novel, thereby linking the two. Some characters, such as Mother Ste. Barbe, have names taken from local place names, thus locking the individuals into the fabric of the locality.

NATURE-BASED SPIRITUALITY IN I SAW WATER

Shortly after Charlotte arrives unexpectedly on Ménec, Sister Brigid offers some surprising advice to her troubled cousin: “Springs, trees and rocks have a self-acting power: they’re not interested in your faith. Just follow the rites, and the virtue will come through” (page 54). These words, coming from the mouth of a Catholic nun, are heretical. By claiming that natural objects—including those normally regarded as inanimate—contain a life force that can be engaged through the observance of ritual, she is placing her personal experience above doctrine and gnosis above faith.

However, had Brigid not been a nun but, say, a New Age neo-pagan or Druid, her words would have been entirely uncontentious. To followers of such spiritualities as these, a belief in the healing powers of natural objects and places is fundamental. Repeatedly in I Saw Water, Brigid and her mentor, Sister Paracelsus, are portrayed as practically and spiritually in tune with Nature in a manner that places them at odds with conventional Catholic doctrine. In fact, there are times when the rituals and beliefs of nature worship—carried out at such places as the Shrine of the Triple Well and the Well-Meadow—seem just as important as Catholic liturgy and dogma.

Today’s pagan spiritualities exhibit a postmodern attitude toward truth, authority, and objectivity. They are characterized by an openness to personal interpretation and development in ways that dogmatic (in the literal sense of based on officially sanctioned belief) theologies are not. It is instructive in this regard to compare the Celtic figure of Brigid, in her emerging twentieth-century form, with the Roman Catholic figure of the Virgin Mary to see how the main models of female spirituality in I Saw Water differ. Mary, of course, is not a goddess, but she is the nearest thing that Christianity has to a female deity. As an intercessor for women and for the weak and powerless, she takes a subservient role to the all-powerful male deity (not to mention an authoritative all-male clergy). The Celtic Brigid, however, does not carry this burden of oppression by a male deity. Her “pre-Christian status allows her to function within the guiding mythology of neo-pagan ritual as representative of an ancient earth-centred and woman-centred spirituality.”18 Just as the increasing importance of women in occult societies had mirrored the increasing independence of women in Victorian society, so too did the development of pagan and goddess spiritualities in the mid-twentieth century reflect the increased secularization of Western society, coupled with a suspicion of institutional religions and a steady decline in their authority. The Druid Order, for example, encouraged its members (including Colquhoun) to discover their own individual relationship with the divine, however it was revealed—through God, Goddess, Great Spirit, or some other source. The Fellowship of Isis (of which Colquhoun was also a member) has always simply required members to love the Goddess, irrespective of any other beliefs or affiliations they might hold.19

We have already noted the importance of personal and place names in establishing the spiritual context of the novel. Sister Paracelsus, the novice mistress, is particularly important in this regard, because one of the ways in which Colquhoun distinguishes the spirituality of the Ianua Vitae Convent from that of Catholic orthodoxy is through her name. Sister Paracelsus is known in the vicinity of the convent as “La Druidesse.” Through her name, ancient knowledge, and practical skills, she maintains a link between pagan beliefs and Christianity. The religion of the Gauls (and ancient Britons) is said to have been Druidism. Meeting in sacred groves, the Druids forged a close partnership with the powers of the earth and developed a deep understanding of the healing properties of herbs, trees, and plants. The extent to which this picture is historically accurate is open to doubt. Where apologists see an unbroken tradition, scholars see a fantasy construction originating with eighteenth-century antiquarians that has little connection to historical reality.20 In its mid-twentieth-century form, Druidism owed a good deal of its popularity to Robert Graves, whose book The White Goddess (1948) proposed the existence of a tripartite deity, the White Goddess, who presided over Birth, Love, and Death.21 Colquhoun’s own indebtedness to Graves is clear throughout I Saw Water, not least in the person of Brigid.

Several years after the completion of I Saw Water, the influence of Graves remained strong. Colquhoun explicitly expressed her debt to him when, in 1972, she dedicated her illustrated poetry volume Grimoire of the Entangled Thicket to “The White Goddess.” In the title, Colquhoun couples “grimoire,” an archaic word for a textbook of magical practice, with “the entangled thicket,” a phrase from the Hanes Taliesin, a traditional Welsh poem about a shape-shifting hero named Taliesin. Deciphering the meaning of this poem (at least to his own satisfaction) was central to Graves’s understanding of Celtic mythology. In The White Goddess, Graves also wrote about the Celtic tree calendar and the tree alphabet, in which the name of each letter in the Ogham alphabet (an early script used in parts of Ireland and Britain and, allegedly, for secret communications by the Druids) is also the name of a tree or plant, linked through the flow of its sap to a month of the lunar year. One drawing from the Grimoire, entitled Beth-Luis-Nion on Trilithon (fig. 4), shows how the Ogham letters can be nicked on the stones that form the classic Stonehenge trilithon. This allowed Graves to relate each letter to its appropriate tree and to construct the complete Beth-Luis-Nion (Birch, Rowan, Ash) calendar. Each poem in Colquhoun’s collection was inspired by one of the months or festivals of the pagan calendar. So, for example, the poem “Muin” relates to September, the month of the vine tree.

Colquhoun, whose interest in covert forms of communication is evident in a number of passages in I Saw Water, returned to the tree alphabets in an unpublished essay written in 1966, “The Tree Alphabets and the Tree of Life.” The Barddas referred to in the essay is a collection of Welsh writings, ostensibly medieval but largely written by Edward Williams (1747–1826) and published posthumously under his bardic name, Iolo Morganwg. It contains a mixture of mystical Christianity, Arthurian legend, and an entirely invented system of writing, the “Coelbren y Beirdd,” or “bardic alphabet,” supposedly the alphabet of the ancient Druids. It also proposes a cosmic system of emanations, or rings of existence, that has similarities with the Qabalistic Tree of Life and which was of particular interest to Colquhoun. She undoubtedly knew of the false provenance of the writings but must have felt that they contained authentic insights into ancient lore and scripts, important enough for her to tease out their meanings and associations.22

As a member of both English and French Druidical orders, Colquhoun’s engagement with Druidry was practical as well as theoretical. In 1961 she traveled to France with Ross Nichols, one of the leading lights of British Druidry. They were joined there by Robert MacGregor-Reid, the chief of the Druid Order.23 Modern Druidry has close associations with heterodox Christianity, and during the visit Colquhoun was ordained a deaconess in the Saint Église Celtique en Bretagne—the Ancient Celtic Church.24 After the celebrations, she and Nichols toured Brittany visiting churches, holy wells, and prehistoric sites. Some of the material she collected at this time was incorporated into I Saw Water.25 Nichols split from the British Druid Order in 1964 to form the separate Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids, named for the supposed three elements of ancient Druidry: bards (poets and singers), ovates (masters of occult lore), and druids (philosophers and thinkers). Colquhoun, while attempting to reconcile the two factions, continued her formal allegiance with the old British Druid Order, taking part in a number of its regular equinox ceremonies.

Colquhoun’s own belief in an earth power that can be detected at a local level, such as the one that can be experienced at the Ianua Vitae Convent’s Well-Meadow or the nearby Hill of Tan, finds expression throughout her writings and in several paintings. Although the force is felt locally, she understood such manifestations not as separate, isolated, or self-contained, but as part of a global power that girdles the earth. Places where the earth force is particularly strong become places of worship: Neolithic stone circle; Druidic grove; holy well or Christian church. At these places, Colquhoun envisaged streams of energy, generated within the earth, emerging or erupting as geysers. She shows this clearly in the oil painting Dance of the Nine Opals (1942; fig. 5), which features the Nine Maidens, a stone circle in Cornwall. The energy stream wells up from a subterranean source, and glowing stones are joined by encircling lines of force. Colquhoun summarized the complexity of the painting’s symbolism in an explanatory note (pages 165–66).

In a much later text entitled “Pilgrimage,” published in 1979, she declares that this spiritual power spouts from the body of Hecate, the Great Earth Goddess. The identification of the earth force as specifically female is an ancient belief that can be traced back at least as far as the Chaldean Oracles. It was discouraged by patriarchal monotheistic religions for their own obvious reasons, but interest in Her was rekindled in the late eighteenth century by Romantic writers who initiated a nostalgia harking back to supposed goddess-worshipping and women-centered societies of the ancient Middle East. It became a popular trope in the nineteenth century among utopian social reformers and Victorian occult societies. It influenced twentieth-century occultists, in particular Colquhoun’s mentor in occult matters, Kenneth Grant, with whom she studied in the early 1950s. It is found in Gardnerian Wicca, Druidism, and feminist neo-paganism. In other contemporary manifestations, it has been incorporated into certain strands of radical environmentalism. At its most extreme, it is a theory of nature that not only casts divisions within the human world as false, but also seeks to blur or even deny distinctions between the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms.

Such a belief in an animating force that is present throughout all nature is, of course, roundly rejected by mainstream scientists. But it has never been confined simply to minority spiritual groups. In the twentieth century, it attracted panpsychically inclined philosophers, psychoanalysts, and others who rejected post-Enlightenment materialism.26 Colquhoun tried to keep a foot in both camps and did not believe that the scientific and the spiritual were necessarily incompatible. In her essay “The Night Side of Nature” (1953), she attempted a reconciliation between contemporary sciences and the apparently discredited old worldview. Drawing on ideas derived from modern psychiatry and biology, she claimed that not only are all things in nature linked but, consequently, the forces that shape human nature are to be found throughout the natural world.27 The skeptic will point out that her psychiatry is outmoded, her biology is confused, and her argument that friable rocks exhibit the same process that accounts for the splitting of the human personality is merely fanciful. Yet her claim that human characteristics reflect universal processes is no more than a contemporary expression of the traditional occult dictum “as above, so below.” Similarly, her remarks about the importance of overcoming duality in nature, as evidenced by splits in the psyche, splintered rocks, and the divided genders, can be regarded as examples of the alchemical search for conjunctio.

OCCULT GENDER IN I SAW WATER

Through its name alone, the Parthenogenesist Order takes the reader not into the world of reproductive biology but into the very different world of hermetic gender. In biology, parthenogenesis refers to asexual reproduction, but Colquhoun is dealing with the route to spiritual perfection. This is not an inappropriate mission for a religious order, but in the hands of the nuns at the Ianua Vitae Convent, it cannot be said to represent mainstream theology.

In Western esoteric traditions, certain writings of many different groups, including Qabalists, Gnostics, Neoplatonists, Swedenborgians, and Theosophists, assert that male and female properties were originally contained within one and the same body.28 It is claimed that Adam was an androgynous being whose fall from grace in the Garden of Eden was signified by his splitting into the two separate genders that exist today. Redemption will occur when the duality of gender is transcended and male and female are reunited in wholeness and completion. Colquhoun further believed that, since Adam was originally hermaphrodite, then God, in whose image Adam was created, was also hermaphrodite. She nurtured a deeply held suspicion that the translators of the Bible deliberately suppressed God’s feminine aspects. For Colquhoun, as for other advocates of this viewpoint, spiritual advancement lies in overcoming the polarities of the separated genders and the achievement once again of the hermaphrodite or androgynous whole. (It is never entirely clear whether the united genders will have the secondary sexual characteristics of both or neither; ultimately, Colquhoun thinks, it does not matter, since we will evolve beyond materiality and exist only as thought-forms.)29

The use of gender-conflating names in I Saw Water reflects this pursuit of spiritual perfection through unification. Examples include Mary Fursey, Mary Paracelsus, and the place name Kervin-Brigitte. Widening the focus beyond I Saw Water, we might also consider Colquhoun’s painting Linked Islands II (1947; fig. 6). It is one of a series of works painted to elucidate the poetic sequence “The Myth of Santa Warna,” in which she also explored the theme of gender unification, together with the nature of a sexualized landscape.30 The watercolor was painted using an automatic technique known as decalcomania, which allows the artist to capitalize on apparently chance effects. Linked Islands II presents an aerial view of St. Agnes, one of the Scilly Isles that lie off the coast of Cornwall. It interprets St. Agnes, with two of its ancient monuments, as a sexualized landscape. Depending on the state of the tide, St. Agnes is two in one. At low tide it is one island, and at high tide it becomes separated into two smaller land masses, linked only by a slender sand bar. Each islet has its own gender identity. St. Agnes is the site of a holy well, shown on the left of the painting. Water, as always in Colquhoun’s work, symbolizes the female force. The islet of Gugh on the right, with its prehistoric phallic menhir known locally as the Old Man, is the male counterpart. When, at low tide, the two are united in conjunctio, they become the “hermaphrodite whole” of the alchemists.

Colquhoun’s interest in the byways of Christian mysticism led her to the writings of the seventeenth-century Flemish mystic Antoinette Bourignon. If the separation of the genders at the Fall is an idea shared by many writers, Bourignon’s account of the creation of Jesus appears to be unique to her. Her vision was illustrated by Colquhoun in the watercolor Second Adam (ca. 1942; fig. 7). According to Bourignon, before Eve was created, Adam wished for a companion to join with him in prayer and the glorification of God. He set out to make one. Inside his abdomen, in place of intestines, Colquhoun’s Adam has what looks suspiciously like an alchemist’s furnace and retort, in which he brews the second Adam.31 After he is born, God looks after the young Adam and, in due course, implants him in Mary. In this way, the firstborn of the androgynous Adam became Christ.

DREAMS AND I SAW WATER

Throughout her entire adult life, when she woke from dreaming sleep, it was Colquhoun’s practice to make an immediate written record of the dream and jot down other features that struck her as relevant, such as her mood on awakening. She would sometimes supplement these records with small sketches of objects or people she had encountered during the dream. As she worked on I Saw Water during the 1960s, she combed through her diaries, selected recent dreams as well as others extending back over some twenty years, “cut and pasted” them together, and linked them with consciously composed narrative passages (see fig. 8). She also provided the Breton setting for the events and added appropriate place and character names, as we have earlier discussed. Any changes that she made to the dream material itself were minimal.

Colquhoun assigned such great importance to her dreams that they provided the source material for virtually all of her imaginative prose, much of her poetry, and a number of her paintings. Although the extent to which she relied on dreams for her raw material was unusual, the very fact of doing so was not: dreams have inspired artists and writers for centuries. However, during her lifetime, a revolution in the understanding of dreams took place. It is a legitimate question, therefore, to ask what she understood herself to be doing when recording and making use of her dreams in this way. When she dreamed, did she suppose that she was delving into her personal past and that her dreams could help her understand her fears and insecurities? Did she perhaps imagine that she was tapping into shared ancestral memories? Did she think that she was receiving spiritual illumination, maybe opening up channels of communication between physical and incorporeal worlds? Did she believe that she was traveling into ethereal territories, using faculties that were unavailable to her in the waking state? It is unlikely that she would have made use of her dreams in the ways she did had she thought that they held no intrinsic meaning—if they were, say, merely a by-product of her brain cells performing routine maintenance tasks while she slept, or if they were caused by indigestion. In this section, we discuss the reasons why her dreams assumed such significance in her life.

The primary reason was that she considered dreams to be an important method of acquiring occult knowledge. Such a view is not new. For the first four thousand years of recorded history, most people believed that dreams contained messages from the gods. Philosophers and skeptics might have quibbled or debated the details, but for the majority, dreams contained divine guidance and should, if possible, be acted upon. It is true that some dreams are so bizarre that one might wonder whether they came from demons rather than gods, and it is also true that some dreams, when acted upon, have led to personal, political, or military disasters, but this merely points to difficulties of interpretation. To mitigate this, priestly guidance was always available.32

During the Enlightenment, the growth of rationalism led to the decline of supernatural explanations for dreams. These were now condemned as superstition. It fell to occultists and astrologers to keep belief in the external origin of dreams and their prophetic nature alive. In fact, in the face of growing scientific opposition, occultists hardened their position, coming to define dreaming sleep as a privileged state. Rationality, it was claimed, was at its weakest during sleep. Sleep, therefore, is the time when we are closest to the gods and most receptive to godly messages.33

By the end of the nineteenth century, diverse theories about dreams were in circulation. The cultural environment of the Victorian period was sufficiently rich to support the rise of science and secularization while, at the same time, hosting a resurgence of magic and spiritualism. The intellectual context was the complex interface between established sciences such as physics; emerging sciences such as psychology; marginal sciences such as mesmerism; and supernatural and occult traditions. Some empirical scientists studied the role of memory, emotion, and sensory stimuli on dream content and rejected occult explanations. Others, such as those associated with the London-based Society for Psychical Research (founded in 1882 and numbering eminent physicists, philosophers, and psychologists among its members), while often rigorously skeptical by the standards of the day and even agnostic, were more prepared to accept the existence of telepathic and precognitive dreams, and even to undertake practical experiments with mediums in the hope of making contact with spirits.34 As far as the mechanisms underlying telepathic phenomena were concerned, new explanations represented little advance on the proposal first made in classical Greece that happenings in one place may be transmitted to another location by vibrations. Rather than “vibration,” however, Victorian theories were couched in contemporary vocabularies of electricity and magnetism and the ether physics that had dominated since Thomas Young demonstrated the wave properties of light in the early nineteenth century. Many noteworthy scientists of the Victorian period, such as Peter G. Tait and Balfour Stewart in their popular book The Unseen Universe; or, Physical Speculations on a Future State (1875), ascribed spiritual and mysterious properties to the ether. The former president of the Society for Psychical Research and eminent scientist Sir Oliver Lodge, author of the classic The Ether of Space (1909), continued to argue for the ether hypothesis well into the 1930s, after it had been abandoned by most physicists.

At the more magical end of the spectrum, members of the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn either remained largely untouched by mainstream developments in the physical sciences or turned to them to justify their occult convictions.35 These were the two most important occult societies established during the second half of the nineteenth century. The Theosophical Society was formed in New York in 1876 under the leadership of the Russian émigré H. P. Blavatsky and the American lawyer Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, who had distinguished himself as a member of the three-man commission charged with investigating the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The Golden Dawn, founded twelve years later, was based in London but also had temples elsewhere in the United Kingdom and in the United States and France. Members of these occult groups attempted to capitalize on the cognitive authority of science by quantifying and systematizing their learning in ways that resembled those of science. But most of them were opposed to scientific materialism, focusing instead on strictly nonrational methods of surrendering the self to occult forces. Freed from the physical body during sleep, they argued, the spirit is free to travel in nonmaterial, astral planes, meeting and conversing with other spirits. When the sleeper awakes, these journeys are remembered as dreams. This claim opened up the possibility that astral travel can be developed and taught. Perhaps astral meetings between two sleeping occultists could be prearranged, resulting in a shared dream. The Golden Dawn provided magicians with detailed instructions on “scrying in the spirit vision,” as they termed such practices. The astral meetings between two Golden Dawn initiates, W. B. Yeats and Maud Gonne, had the result that “their famous love affair, frustrated at mundane level, achieved a hidden consummation.”36

As a member of the Theosophical Society and one-time applicant to the Golden Dawn, Colquhoun absorbed these teachings. In the early 1950s, while studying for advancement in a Golden Dawn successor organization, the Ordo Templi Orientis, she summarized the multiple ways in which she believed the practicing magician might acquire magical knowledge during dreaming:

The night dream, when suitable, can be used for definite magical aims, either through the information it gives in symbolic terms[,] thereby helping to clarify the magical will, or through the initiation it confers [and] which gives the desire to know more. Guidance ([the] solving of problems [is] not perhaps definitely magical enough). [Other examples are] the pre-cognitive dream, the shared dream, the telepathic dream [and] the directed dream (induced by objects under the pillow). Suggestions taken from a dream can be used in magical ritual.37

Today, these ideas appear eccentric, but had Colquhoun been living in Babylon at the time of Gilgamesh, and had she inscribed her words in cuneiform on tablets of clay, they would not have raised an eyebrow. Her recommendation of placing an object under the pillow in order to influence the content of a dream derived directly from the technique of “dream incubation,” which was widely practiced in ancient Mesopotamia.38 Similarly, when she mentioned the “gates of horn” in her poem “Muin,” she was referring to the ancient Greek belief that predictive dreams can be distinguished from false or deceptive dreams by their mode of delivery to the dreamer, through one or the other of the two Gates of Hypnos.

A dream, as a channel for occult revelation or communication, while providing the dreamer with a route into the spirit world, also opens a channel in the reverse direction. The result may be more than the dreamer bargained for: spirits or demons may visit him or her, whether invited or not, and leave a mark of their presence on the dreamer’s astral body. This subsequently becomes imprinted on the physical body. The poem “Wedding of Shades” relates one of Colquhoun’s own experiences of this sort.

Contact, however, was more often verbal than physical. The name of the Parthenogenesist Order and the nature of its mission were revealed to Colquhoun in a dream of May 8/9, 1956. In a dream several years earlier, in 1942, she had heard a disembodied voice saying, “This is the grotto of the sun and moon, Nicaragua.” So strong was the impact of this message that she reflected upon its meaning for the remainder of her life. It inspired her to research the topography and archaeology of Nicaragua, where the dream grotto was evidently located, and it became the subject of the oil painting Grotto of the Sun and Moon (1952). She finally concluded that “the Grotto was an occult centre used by an eponymous order which existed in the past or still exists, either in that state of being commonly recognised as reality today, or else in regions variously called the Higher Worlds or the Inner Planes.” For some reason, she had been granted a glimpse of this mysterious center: “And now if I receive an idea or perception which does not seem to be a direct result of anything I have read, heard or thought, I take it to be a message from the Order.”39

The publication of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams in 1899 marked the beginning of a revolution in the study of dreams.40 Although Freud continued to recognize the traditional standpoint that dreams could provide helpful guidance for the dreamer, his reason for doing so was anything but traditional. In his view, it was not because of any divine source, the possibility of which he categorically rejected, but because dreams revealed the dreamer’s hidden fears, hopes, and desires. The information contained within the dream, however, was coded, disguised by subconscious censorship. This was why dreams were largely unintelligible to the dreamer. The expertise of a skilled interpreter was still required to understand them. This function was no longer to be fulfilled by a priest, as of old, but rather a psychoanalyst.

Freud’s materialistic view of the world explains his rejection of the existence of prophetic dreams and the spirit world, although he was still prepared to accept—even at the height of his professional eminence and albeit hesitantly—the possibility of telepathic dreams.41 His core belief that dreams were firmly rooted in an individual’s unconscious also caused him to reject the dramatic assertion by his colleague Carl Jung that some aspects of the unconscious are shared and common to all humanity. According to Jung, some dreams come from a region of the mind termed the “collective unconscious,” a depository of memories, images, and mythologies from the ancient past. Although they are largely forgotten at a conscious level by modern civilized Europeans, they may be accessible during sleep, when rationality is suspended. They reflect a natural wisdom deep within the human unconscious. They connect the dreamer with the past and provide insights that can give guidance along the path of self-development.

It is hardly surprising that some of Jung’s ideas, including suspended rationality and the shared unconscious, which he frequently expressed using the language and concepts of alchemy, found a receptive audience among many occultists. For several years during the 1950s, Colquhoun herself was associated with the London-based Buck Research Unit in Psychodynamics, run by Alice Buck, a Jungian psychotherapist. Although its duration is unclear, Colquhoun also underwent a period of psychotherapy with Dr. Buck, who was prepared to analyze her dreams by letter in addition to meeting with her in group therapy sessions. The Jungian context of the research unit is clear from Colquhoun’s brief account of its activities, “Divination Up-to-Date.” The research interests of the group included the extent to which shared dreams could be analyzed and used to predict natural or man-made disasters. Buck disagreed with occultists on some points and regarded shared dreams (which might include clairvoyant content) as instances not of astral travel but of two individuals “inter dreaming”—that is, simultaneously accessing an aspect of the shared unconscious. In 1950, Colquhoun and Buck experienced one such shared dream, consisting of geometrical forms, which were later used as the design for the dust wrapper of the book in which Buck gave her own account of the research unit’s activities.42

For his part, André Breton had no doubt as to the central role of dreams in the surrealist quest for truth. Basing many of surrealism’s investigatory methods on Freud and contemporary psychiatry (including the study of dreams and hallucinations, and the use of automatic writing and free association), Breton regarded it as a fundamental truth that the world of dreams and the waking world are but one; both are of equal importance, and each is as incomplete as the other. In place of the traditional viewpoint that treats dreaming and the waking state as opposites, Breton wanted to substitute reciprocity—hence the metaphor of communicating vessels that he developed in Les vases communicants (1932), the book that contains his most detailed discussion of dreams.43 Breton imagined existence as two interconnected containers, one being the dream state and the other the waking state. Because they are constantly connected to each other, they are in a state of equilibrium and material can flow freely in either direction.

Despite the enthusiasm that the surrealists showed for his work, Freud regarded some of Breton’s ideas as an almost unintelligible distortion of his own. For example, in an assertion that put him completely at odds with Freud’s position, Breton tried to show that space, time, and causality are identical in both dreams and reality. In other words, they are both objective states, rather than one (the dream) being no more than a subjective mental process. If Breton’s view is accepted, one consequence is that traditional views of time must be rejected. In material reality, anticipation of historic time is an impossibility. In psychic time, however, knowledge of the future in the present—or, indeed, multiple futures in multiple presents—is perfectly possible. Some Jungians also disagreed with Freud on this point. Alice Buck, for example, when attempting to explain predictive dreams, was content to accept that paranormal events occur outside of time as it is ordinarily understood. She believed that conventional linear time is a creation of consciousness that can be escaped during dreaming. In its place, she adopted the concept of “serial time,” in which the “future” in our three-dimensional world is simply the “now” viewed from elsewhere in a multidimensional world with infinite planes of existence.44

Time, as Breton put it, contains “the perfect continuity of the possible with the impossible.”45 Further, if there is no difference between dreamed representations and real perceptions, then the imaginary and the real are one and the same thing. The realization that the one-way flow of time is an illusion is a consequence of this. Ultimately, we can no longer tell which came first, as the difference is artificial. Additionally, it cannot matter at what rate, or in what order, images that are later seen to be connected are released into consciousness—nor, indeed, whether they are first perceived in the dreaming state, the waking state, or some combination of the two. It is this that makes it possible for certain dreams to prefigure episodes in waking life. It is this that allowed Breton to claim that his poem “Sunflower” was an accurate description of a person he had yet to meet (and whom he subsequently married),46 and Colquhoun, in I Saw Water, to compose a sequential narrative in which the constituent dreams had occurred over a period of many years and in no logical or temporal sequence. The novel was dreamed episodically, like a serial in a magazine, but a serial in which the episodes were published in no discernible order, with no ex-ante structure and at apparently random intervals.

AUTHOR OR MIDWIFE: WHO WROTE I SAW WATER?

Colquhoun’s method raises questions about authorship and originality: Who, exactly, wrote I Saw Water? Colquhoun undoubtedly had the dreams, wrote them down, and ordered them, but if she saw herself as a channel through which a hidden intelligence, or intelligences, communicated, then her task was more that of editor than author. The principles that governed her selection of which dreams to include in the final text are nowhere explicitly stated, but the evidence suggests that she regarded each of the dreams she included as a fragment of a greater whole, and that her task was to piece together a hidden, but gradually revealed, original. Examination of her dream diaries shows that during the period of active composition, she was adding dreams to the narrative as they occurred. In a footnote to one transcription, written when the novel was nearly finished, Colquhoun ruefully added that if the dream had to be included, this would entail a great deal of revision (see fig. 8). She clearly felt that she had limited personal choice in selection, but, in the end, the dream was not required.

One way of approaching the question of authorship is to ask whether I Saw Water is an automatic text. Automatism lay at the heart of surrealism. Indeed, Breton had originally defined surrealism as “psychic automatism in the pure state.”47 In other words, by writing rapidly and without pause or reflection, by drawing or applying paint in a spontaneous, unplanned, and unregulated manner, it was hoped to bypass the mind’s critical faculties and so provide access to deeper, more fundamental levels of the psyche. Some surrealists were happy to accept dreams as automatic phenomena. The argument in favor is clear: to put it at its simplest, conscious and critical control, by definition, cannot be exerted during dreaming sleep. Others were skeptical. The act of translating dream images into words, the unavoidable period of transition from dream state to waking state, and the inevitable passage of time between dream and transcript all increased the likelihood of conscious selection, memory failure, and the imposition of a structure that the original dream may not have possessed.

Approaching the problem from a slightly different angle, I Saw Water, composed almost entirely of material assembled from dreams, is a collage novel. As M. E. Warlick noted in relation to Max Ernst’s collage novels, because of the way in which this kind of text transforms its materials to give birth to a new creation, it is a form of alchemy.48 Ernst’s novels used engravings and woodcuts as their source material, but Warlick’s argument applies equally well to I Saw Water. Colquhoun’s dreams form the prima materia with which the work commences. They are taken apart, recombined, and fused, not by fire in the alchemist’s furnace, nor by adhesive in Ernst’s gluepot, but by Colquhoun’s imposition of a narrative structure. Colquhoun had no doubt that collage, using either words or images, was an automatic technique. To her, it was on equal footing with the “found object,” another surrealist method for stripping an article from its manifest meaning. “Surely,” she wrote, “such objects are found through the use of the automatic faculty.”49 Further, she might have added, the juxtaposition of apparently unrelated objects, which brings out hidden affinities between them, is not far removed from the pursuit of correspondences in occult research. Indeed, the discovery of hidden links is the very stuff of magic.

If we allow that dream transcription is a species of automatism, the problem still remains: where does automatically generated material actually come from? At first, the answer seemed clear: it came from the unconscious. Automatic writing was just like taking dictation from the lower reaches of the mind. As Max Ernst expressed it, the use of automatic methods led to the author being revealed as “a mere spectator at the birth of the work.”50 It was noted, however, that during the surrealists’ early experimental sessions with automatic writing, the participants sometimes entered a trance state, recalling the practice of spiritualists and mediums who claimed to be in communication with the dead. Over time, the explanations for automatically produced material ranged from the occult at one extreme to contemporary physical science, including particle physics, at the other.51

All of this amounted to what Nicolas Calas termed a “crisis of automatism,” leading some to turn away from automatism entirely.52 For Colquhoun, the nature of automatism was clear and unproblematic. She drew out the similarities between surrealist automatism and the attempts of spiritualists to contact noncorporeal entities: “It would seem that the only significant difference in method between the two types of automatism is the fact that the surrealist is his own ‘medium.’ ”53 In other words, the source of the material is external, but another person is not required as an intermediary in order to make contact with the source. If this explanation is accepted, it shifts us away from a narrow consideration of a person’s relationship with their unconscious to a much broader, mystical consideration of humankind’s relationship to nature.54

In fact, some surrealists, including Breton, had always displayed mystical leanings. For a time, this seemed to be the direction that surrealist painting might take, were it not for the disruption of World War II. In the summer of 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, Colquhoun took part in theoretical discussions with some of the younger surrealist painters in the Rhône Valley, where they had rented the Chateau de Chemillieu. The participants included Roberto Matta, Wolfgang Paalen, and Gordon Onslow Ford, who were developing a style of automatic painting that has become known as “psychological morphology.” The existence of these debates is well known, but Colquhoun’s participation in them, however fleeting, has almost been forgotten. When Matta and Onslow Ford fled to New York at the outbreak of World War II, their ideas and methods helped influence a generation of American artists at the birth of the movement now known as abstract expressionism.55

The paintings produced under the influence of psychological morphology, in particular those of Matta, with their multiple perspectives and deep pools of color, often appear to conquer the limits of space and time. Beings or personages appear that seem to belong not to the known world but to worlds that lie beyond our experience and understanding.56 Perhaps, said Breton, we share the planet with other creatures that, through camouflage or some other means, are able to escape discovery. We cannot begin to imagine the nature of these beings, whose behavior may be as strange to us as ours is “to the mayfly or the whale.”57

Colquhoun responded to Breton’s remarks about the invisible ones with the automatic watercolor Un grand invisible (ca. 1943; fig. 9) and the poem “Les Grandes Transparentes.” In the final line of the poem, “And if they should call, can we answer?,” we hear the voice of the practicing occultist. Establishing contact with spirits, elementals, and other entities is a major aim of the magician. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that all such beings are benign: as Colquhoun recounted in “Wedding of Shades,” they might bite. Through the use of appropriate containing and banishing rituals at the onset and conclusion of their ceremonies, magicians seek to ensure their personal safety. Colquhoun was always alert to the dangers of unwary or unskilled magicians unleashing malign forces that were beyond their competence to contain. She was critical of those surrealists who investigated automatic or occult phenomena from a position of comparative ignorance. They were dipping their toes in dangerous waters. By not paying due regard to protective ceremonies, many paid a great price: “The movement’s approach to esoteric study and experiment was too diffuse and sporadic to impress a naturally sceptical world. From the human angle, it may be added that the high proportion of suicides and other tragedies among its adherents is characteristic of psychic exploration without adequate safeguard.”58

COLQUHOUN THE MAGICIAN

Colquhoun’s position as a female occultist in the mid-twentieth century was, in some ways, privileged, but in others problematic. Historically, she was one of the first generation of women who took part in ceremonial magic as of right and as equals to men. Prior to the pioneering work of women such as H. P. Blavatsky (1831–1891), Anna Kingsford (1846–1888), and Moïna Mathers (1865–1928), the occult had been an all-male preserve. These women exerted a lasting influence on the occult scene, paving the way for influential female near-contemporaries of Colquhoun, such as Dion Fortune (born Violet Mary Firth; 1890–1946), whose Society of the Inner Light rejected Colquhoun as a member in 1956, and Tamara Bourkhoun (1911–1990), whose Order of the Pyramid and the Sphinx accepted Colquhoun as a member in the 1970s. The new status of women, not just as participants in occult activity but as founders and leaders of hermetic societies, was, in part, a consequence of changing social conditions, but it also owed much to the concurrent development of a specifically female spirituality.

One of the key figures in the latter process was the Frenchman Alphonse Constant, better known today as Eliphas Lévi (1810–1875). Lévi, whose influence on occultism in France and England is still felt, closely identified Woman with the powers of nature: she was an elemental energy, a prophetess, a transforming life force. In the words of Moïna Mathers, “Woman is the magician born of nature by reason of her great natural sensibility, and of her instinctive sympathy with such subtle energies as these intelligent inhabitants of the air, the earth, fire and water.”59

Emotional and sexual attachment to a woman, then, is to achieve proximity to elemental powers. Lévi’s views helped form those of André Breton, for whom love and desire occupied a central place in surrealist transformation. The glorification of the power of desire and its capacity to challenge conventional moral and social constraints formed part of the surrealist program, in the belief that it would lead to social as well as sexual revolution. However, while surrealist language and imagery eroticized the female body, it did so, paradoxically, by treating it destructively through distortion and dismemberment or by treating it as a passive object of male desire. It was a contradiction that was never resolved: most male surrealists were quite unable to live up to their revolutionary precepts. Their treatment of women remained a projection of traditional male fantasies; women were revered but simultaneously feared, objectified, and debased.

For the women who were drawn to surrealism, this represented a challenge that was both personal and philosophical. Some resigned themselves, more or less unwillingly, to the role imposed upon them as muse. Some, such as the artists Toyen and Claude Cahun, rejected gender stereotypes, in life as well as in art, each living a life of gender ambiguity. Others made use of Lévi’s recently established links between the hermetic tradition and women’s creative powers. If recognition of their unique spiritual powers offered nineteenth-century women a way forward from their social, biological, and reproductive bondage, the same might be hoped for by women attracted to surrealism.60 Leonora Carrington, for instance, often used alchemical symbols in her art and writings, while Remedios Varo frequently depicted the paraphernalia of magic: crystal balls, alchemical laboratories, retorts, alembics, and ritualistic activities. What sets these artists apart from Colquhoun, however, is that for all their theoretical knowledge and occasional practical ventures—Varo, for example, is known to have consulted the I Ching before making important decisions61—they were primarily consumers of magic rather than contributors to the development of magical knowledge. They drew upon established traditions, but more as a source of pictorial imagery than inspiration for their own research. Unlike Colquhoun, they did not develop or modify ritual practices or make magical discoveries of their own. Further, the playful whimsicality and theatricality that frequently suffused their work is entirely absent from that of Colquhoun, whose attitude toward magic was always studious and respectful.

In the popular imagination, magic and divination are associated with the use of a crystal ball. However, this is not mandatory and, in practice, any reflective surface will do. As many magicians had done before her, Colquhoun used a mirror for divination. Hers was nineteen inches in diameter, with an ornate hand-beaten copper frame that she had made by a local craftsperson. When not in use, to keep it from prying eyes and preserve its accumulated magical powers, she kept it wrapped in a lace shawl, knotted with three double knots, to harmonize with three knot-work bosses on the copper frame (fig. 10). The knots were then wrapped round with a yellow rope, which she called “Um,” short for “umbilicus.” When using the mirror, Colquhoun would wrap one end of the rope around her waist, connecting the other to the mirror. With the shawl over her head and enclosing the mirror, she linked herself to her image in the mirror via “Um.” Identifying her mirror image with her astral body, she projected her consciousness into it and traveled in astral realms.62

In a rare excursion into esoteric Islam, Torso (1981; fig. 11), Colquhoun applies a Western sensibility to an Eastern theme. It concerns the lataif-e-sitta, the six subtleties, or suprasensory organs said by Sufis to be part of the spiritual self, in the way that biological organs are part of the physical body. Sufic development involves the awakening of these dormant spiritual centers in a set order. The lataif are, in sequence, Nafs (blue: ego), Qalb (yellow: mind), Ruh (red: spirit), Sirr (white: consciousness), Khafi (black: intuition), and Ikhfa (green: deep perception). The angular connecting arrow in Colquhoun’s painting indicates the order of awakening, commencing with Nafs, the pale blue background. Many readers will notice the similarity between the subtleties and, in other traditions, the chakras and the sephiroth. Additionally, those familiar with the Golden Dawn will realize that Colquhoun’s method of indicating the sequence derives from the Golden Dawn technique of spelling out an angelic name on a magic square.

Notwithstanding the diversity of Colquhoun’s hermetic interests, a constant focus in her magical life was the Qabalah. Central to this school of Jewish mysticism is the quest to understand the interconnections between all things in the created cosmos. The search is undertaken largely through the study of correspondences. Because Hebrew letters are also numbers, every word can be converted to a number and connected to all other words that share the same number. In this way, slowly and incrementally, God’s plan may be understood.63 The magical practitioner who wishes to construct a ritual with a specific purpose in mind will take great pains to make use of this accumulated knowledge and surround himself or herself with objects that are related to one another and associated with the magical end. For example, as part of her study program with the Ordo Templi Orientis in 1952, Colquhoun developed a ritual to be used by a woman to capture the affections of a man she loved. In other words, it was a good old-fashioned spell. We have quoted at length from the ritual below and published an associated poem to make the point that—aside from all the details concerning the setting, the magical implements, and the appropriate symbols, all chosen for their links with Venus, the goddess of love—a magical ritual is a sensory experience. The magician tries to involve as many senses as possible in pursuit of the desired outcome:

The oratory is hung with silk curtains of bright rose colour rayed with pale green; a circle fourteen feet in diameter is painted on the floor in emerald green, and immediately within it a seven-pointed star in pale green. At each point of the star a light is burning in a copper lamp. In the centre of the star is a heptagonal altar hung with emerald green silk upon which stands a copper chalice containing in liquid form the drug damiana surrounded by a cerise-coloured girdle. To the left of this is a vase made of turquoise holding roses; to the right is a copper censer burning sandalwood, in front a silken pantacle engraved with a beautiful naked woman, the names Kedemel and Hagiel, the sigil of Venus and the Hexagram with the planetary symbol of ♀ in the right lower point. In front of this again is a large emerald engraved with the name Hagith, and a wand made of a myrtle branch.

The operator wears a robe of sky-blue silk, a pendant in the shape of a Pentagram of copper set with emeralds, and cerise slippers. Standing to face the altar, she takes up the myrtle branch and makes with it the invoking pentagram of fire.64

Then, concentrating on the man she desires, she begins to intone the words of the spell. The poem “Love-Charm II” is based on the words of invocation that Colquhoun composed to be spoken at the climax of the rite. Whether she created the ritual for purely educational purposes or with one eye to its practical application is unknown, but why not? Why waste a perfectly good spell?

Magic is, at heart, a practical, experiential, and therefore sensory activity. Although some theoretical knowledge is required, occult advancement is largely acquired through initiation, ritual, and meditation. Colquhoun’s own personal experiences of ritual clearly inform several episodes in I Saw Water. She was undoubtedly expressing her personal view when, during the healing service at the chapel in the Well-Meadow, Sister Brigid remarks that the effect of the music in a religious service is that “the discursive mind is lulled or entranced while ‘the high dream’ takes over.” Although the bishop conducting the service would be unlikely to express it in the following terms, to the ceremonial magician sound is important because the vibrations of the voice are felt on the astral plane and facilitate contact with hidden powers. Similarly, at the height of the ceremony of the Snake Dance (page 57), when Brigid and Charlotte “obtained the Light,” the transforming effect is dependent upon a combination of sound and rhythm.

The importance of sound is further illustrated by the poem “Red Stone.” It is one of a series of eleven poems composed circa 1971 that together make up Colquhoun’s “Anthology of Incantations.” The sequence as a whole is a celebration of the richness of alchemical language and imagery. Each poem consists entirely of synonyms—which may be descriptive, poetical, or allegorical—that have been assigned to a substance or process used in the creation of the philosopher’s stone, the objective of the alchemist’s quest.65 “Red Stone” is a verbatim transcription of a section of the eighteenth-century alchemical text Treatise on the Great Art, with the line lengths adjusted.66 As such, it is a found poem, which Colquhoun regarded as another form of automatism. As the name of the series indicates, the poems are surely intended to be declaimed aloud in order to achieve maximum potency.

The importance that Colquhoun gives to another sensory modality—vision, and especially color—is evident throughout her writings and artwork. Where possible, she chose colors for their magical associations as much as for their descriptive qualities. In I Saw Water, for example, during her stay on Ménec, Charlotte has an affair with her physician. At one point his wife, Gertrud, hands her some letters. Charlotte “saw that there was an enclosure in one of them which was written in red ink on yellowish paper, the rest being in blue on white” (page 80). These colors are not chosen fortuitously. In alchemical usage they signify the two genders. Red (elemental fire) combined with yellow (its spiritual equivalent, philosophical sulfur) indicates the male principle. Blue (elemental water) combined with white (philosophical mercury) indicates the female principle. Using these color combinations, Gertrud signals that she knows exactly what Charlotte and her husband are up to.