Читать книгу A Stranger at My Table - Ivo de Figueiredo - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOslo, July 2011

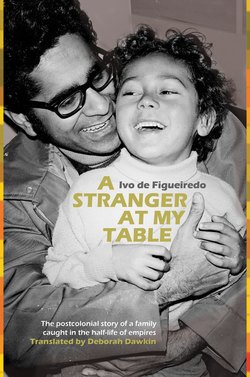

I’VE NOT SEEN OR TALKED TO DAD for over five years. I believe I sent him an email on his seventieth birthday out of a sense duty. Beyond that, we no longer have any contact. As the years have passed I’ve come to think of him as a stranger, some guy who lived with us for a few years, and then disappeared. In the picture below he stands outside Grandpa’s workshop in Bamble. An Indian in the Norwegian snow.

Dressed for the city in a snowdrift in the middle of the forest. For years I’ve looked at this picture and felt it safest that he stay there, at a distance, frozen, tranquil, before the snow melts and stirs everything into motion.

The snow has begun to pile up in my own life now. I can’t leave him standing there any longer. I need to know how he came to be there, how it all began, and why everything went so dreadfully wrong between us. I need to know this now, before everything freezes again.

For the last eight or ten years Dad has lived in Alfaz del Pi on the Spanish Costa Blanca, surrounded by people I’ve never met and don’t know. I could visit him there, but I don’t. Not yet. I’m not ready. Instead, I take a plane to the United States, to Boston, where his sisters live. We sit around the dining table in an old apartment building on Mass Avenue. The apartment is arranged around a long, dark corridor with doors that lead to a series of rooms that all face out toward the traffic. The floors are warped with age. The thin windowpanes keep neither the noise nor summer at bay. The air is heavy with heat, except in the dining room where an air-conditioner roars.

My aunts look at me with the same gentle, empathic gaze I remember so well from their visits to Langesund when I was a child; it’s as though everything I tell them, any feelings I express, become etched in their faces. Though, in fact, they speak with their whole bodies, the way Indian women do. The many years they have spent in the United States have undoubtedly wrought changes in them, but not in their body language; heads that sway as they talk, forefingers that wag. When they get animated, up pops a forefinger, always the right, and always rocking in a perfect sideways arc, back and forth, affirming or negating, as though they need a metronome to maintain the stream of conversation.

Now and then the metronome halts, and the forefinger points straight up in front of two gentle, but penetrating eyes. Then I know that what will follow is important:

“Your Dad got very hurt. He was only nineteen when he left East Africa. And he’d been like a king.”

Dad hadn’t been any kind of king when I knew him. Not in our house. So where was it he’d been king? In Zanzibar, in Dar Es Salaam or Nairobi? In Goa perhaps, or in England? Now that I think about it, I’m not really sure where he came from; whether it was from just one of these places, or all of them. But somewhere in the world, at some point in his life, he seems to have been strong; a king. Then, somewhere along the road, a king he ceased to be.

As I’m about to leave, Dad’s youngest sister emerges from the bedroom carrying a black folder stuffed with old letters. I recognize the flimsy, blue air-mail paper from my childhood. It arouses memories of Dad sitting at the kitchen table reading.

“Your father wanted you to have these.”

The folder holds all the letters he received from his parents and siblings during those difficult years when the family was scattered to the four winds, uncertain whether they’d ever see each other again. Dad wants to give the letters to my brothers and me, but since we’re no longer on speaking terms, his sister has agreed to hand them over to me.

On my flight home to Norway I glance through one of the letters to Dad from his mother, Herminia:

Nairobi, March 19, 1965: “What passport have you got, Xavier?”

I open another, from the following year:

“We are in a desperate situation…”

Then another, also from my grandmother:

“Please, please, start talking to Baby in English, right away, do not talk to him in Norge [sic]…”

Suspended over the Atlantic Ocean I am grasping fragments of a world in my hands, a world and a history that I’ve started to realize is far greater than I’d ever imagined. Confusing glimpses into the thoughts and anxieties of a stranger – Herminia, the grandmother I never met. Baby. Is that me? A voice from a world about which I have a vague notion, but have never known because it is long-gone; a world that went under and disappeared years before he came to us. Dad’s world. And perhaps mine?

THE EARLIEST PHOTOGRAPH I HAVE FOUND of Dad shows him sitting on a lawn. The year is 1939. I assume it was taken in Victoria Gardens, just outside the city of Zanzibar, where the family’s African ayah often took my father and his siblings. It’s unlikely the servant would have taken this picture. My guess is that Grandfather is the photographer. In which case the picture was probably taken on a Sunday, when he was free. The rest of the week he sat in the office of the British District Commissioner shifting papers, while my grandmother, Herminia Sequeira took care of the housework at their home in Vuga Street. On second thought, the picture may have been taken on a weekday afternoon, since he finished work by one o’clock. The pace of life was slow in Zanzibar, even in the British Protectorate Administration. Dad sits there on the grass in the park. What is he looking at? He doesn’t know. His gaze is open, as are his thoughts. He simply is who he is – Xavier Hugo Ian Peter de Figueiredo. Born in East Africa in an Arab sultanate under British rule, he has both English and Portuguese names, has been baptized into the Catholic faith, and has a complexion that bears witness to his Indian Subcontinent roots. When he learned to talk, it was in English, with some Swahili – just enough to communicate with the servants. He only understood scraps of my grandparents’ mother tongue, Konkani – the language of the Goan people – and never learned Portuguese, which my grandmother spoke fluently.

This is Dad. A boy with a wide, open gaze and the whole world running through his young body. In this he resembles his birthplace Stone Town, the city of stone that occupies the natural peninsula in West Zanzibar. With the ocean on both sides, it looks across the island in one direction and the African mainland in the other. It is a city crammed with churches, with Hindu temples and mosques, yet its silhouette is not dominated by showy spires or minarets, but by the simple, whitewashed houses that lie cheek by jowl, forming a labyrinth of alleys and squares. The effect from a distance is of absolute unity and harmony, despite the fact that the architecture here is so diverse, influenced by the Swahilis, the Portuguese, the Arabs, the Indians and British in that order. Only upon entering the city can you see the contribution each ethnic group has made; from the elegantly carved doors, originally Swahili but elaborated upon later by Arab and Indian craftsmen, to the once unadorned outside walls, now graced with decorative balconies, a sure sign that a house belonged to an Indian merchant.

A unique place in the world, Zanzibar also is the whole world in one place, and this was even truer in Dad’s time. The slaves were long gone, and European explorers no longer came here to prepare for their daring expeditions into the heart of Africa. But in and between these houses people of every shade of brown and black, and a few whites, lived out their lives. In the narrow alleyways, in the fruit market and the bazaars, there were coffee merchants who walked along clanking their bowls, women in black with their faces covered, majestic Ceylonese merchants in white robes and hair tied up in a knot, distinguished Arabs, and African porters who came running up from the harbor carrying cases and bags suspended from long bamboo canes. A few years earlier you might have encountered the sultan himself, reclining on soft cushions in an ornate sedan chair, surrounded by servants in livery, sedan carriers and runners, yelling, “Make way! Make way!” Nowadays the sultan sat in the back seat of a large, black car. When it appeared on one of the few roads wide enough to take such a vehicle, there was no choice but to stand respectfully aside.

And everywhere, the fragrance of cloves from the warehouses down by the harbor, newly arrived from Pemba, and from the hamali-carts carrying clove-balls through the streets; with the old women who walked behind them and swept up any cloves that fell onto the ground, sifting them and gathering them in canvas bags as they went.

One of the small boys who stood aside for the sultan was Dad. Yet despite his having described this to us, I’ve never really given it much thought, never fleshed out the image. Dad and the Sultan of Zanzibar. Sitting in school he could see the ocean through his classroom window. St. Joseph Convent School occupied a large building that was so close to the shore that in storms the waves crashed against its walls. Far beyond the horizon to the northwest, beyond the vast continent of Africa, lay Portugal, Great Britain, Europe. From his desk it was 7,712 km to our Swiss-style chalet in Langesund, Norway. In the opposite direction, a slightly shorter distance away of 4,513 km, lay Saligão in Goa, India, the little village that my great-grandfather Aleixo Mariano de Figueiredo had left in order to seek his fortune in East Africa at the close of the 19th century.

Dad’s classroom did not face East, but West. Although this almost certainly meant nothing to him. He simply was where he was. After school he played in Victoria Gardens, or ran carefree in shorts and bare feet in the sand. Whenever Dad reminisced about his childhood in Zanzibar, it was this he’d choose to describe. Running in the sand, happy. Always happy.

I’d sometimes think: If he was so much happier there than he was with us, here at home, why didn’t he just go back?

Occasionally, passenger boats would arrive in Zanzibar harbor packed with tourists. For Europeans, the island seemed plucked out of A Thousand and One Nights. To wander through Stone Town was for them like stepping into an exotic paradise of their own imagining. In reality, the town was neither as exotic nor as old as visitors might believe. The buildings might give the impression of being centuries old, but most were erected in the last half of the 19th century. It was its decay that gave the city its timeless aura. Several of the grander buildings were designed by the British architect, John Sinclair, based on his notions of oriental architecture. The Peace Memorial Museum in Victoria Gardens, Beit el Amani, for example, designed by Sinclair after World War I, has an undeniably oriental air, with its dome and arabesque windows, but it has little to do with the island’s traditions. Sinclair took inspiration from the entire eastern world; a hint of the Arab, a dash of the Byzantine, according to whim. In that sense, Dad grew up like a film-extra in a European orientalist vision, a picturesque dark-skinned urchin running around the streets, the kind of kid whom travel writers described to spice up their books, and tourists were so keen to photograph.

When they fished out their cameras to snap a picture of Dad, or asked him to pose alongside his playmates, it was because they saw him as an exotic motif.

But was that how Dad saw himself? Did he see himself mirrored in these European camera lenses as the native? Or did he identify himself with the photographer – with the European? What went through his mind as he saw the tourists board the boat again, chattering away in his own mother tongue, about all the incredible things they’d seen? He would eventually realize what he was; that while the blood in his veins was Indian, many of the thoughts that whirled around in his head were European. And while his skin was dark, it was clad in western clothes. But wasn’t his blood the same – pure and red – just like everybody else’s? Wasn’t he complete and whole? Just like Sinclair’s buildings, an alloy of various cultures and beliefs, similar to everything on this island that had been fused together over the centuries?

The truth is that my father could feel as whole as he liked, but it was an entirely different matter what other people thought about him; from the farmers in the fields to the British in their offices, or the sultan in his palace. Or indeed, whether the grinding wheel of history – which has continually divided peoples and driven them from one land to the next in the hope of a better life or in flight from a worse fate – would even spare a place for someone like him.

Why didn’t he go back?

Because his allotted place was repeatedly taken from him. The lawn in Victoria Gardens in Zanzibar where he’d sat with his open gaze. And later, the pink housing block in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, and later still the low modernist house in the Goan district of Pangani in Nairobi, Kenya, where he moved before his childhood was spent. Dad had so many homelands, but when the time came and he was living in the Norwegian countryside with my mother and my brothers and me, all these homelands had vanished, were wiped off the map. The only homeland he had left was the land of his forefathers, Goa, on the west coast of India, the village of Saligão, a place he had never seen and knew only in his dreams.

HE WAS ONCE MY WHOLE WORLD, my horizon, and it never occurred to me that his world was other than mine. I was from Langesund. I was Norwegian and so was Dad, even if he did speak rather oddly and called sausages “pilser” instead of “pølser” and occasionally broke into English. Sometimes he’d be gone for a few days and come home with a suitcase filled with spices and foods. The highlight being when he brought out a packet of papadums and dropped them one by one into a pan of sizzling oil. When they’d puffed up, big and crisp, he shared them out between us as we sat around a steaming pot of curry on the table – but just one half each, since he’d have to go all the way to London to get more.

Occasionally people would arrive at our house who were most definitely not Norwegian. They’d be standing there suddenly in the kitchen; exotic men with white teeth and beautiful women in soft silky clothes. Certainly not the kind of guests the locals were accustomed to seeing in the small coastal town of my childhood, despite it having been dependant on international shipping and shipbuilding from time immemorial.

In the photograph on the next page taken in the early seventies, two of my aunts can be seen standing in front of the shipyard in Langesund. Mum is behind the camera and the photograph is taken for a newspaper article in the Telemark Arbeiderblad, where she worked as a journalist. A pair of sari-clad beauties was newsworthy in the area back then; something the local coffee-colored kid who had wandered into shot, was not. I don’t recall this photo session, but my memory of the excitement that accompanied the arrival of these people is palpable. Especially my aunts, with their bright laughter and black sunglasses. To me they were like American film stars, whom fate had magically transported to Langesund. And I fell in love with each in turn as they appeared in our kitchen doorway. Occasionally Dad’s youngest brother would arrive with a guitar and play “Jambalaya” and “Guantanamera” for us, and once Dad came home with an elderly man with chalk-white mane, a white mustache and dark eyes. This man stayed with us for a few months; Grandfather had done the rounds in the States, living with each of his children in turn, now it was our turn to take care of him. Grandfather made me feel on edge; it was as if he was used to being in command, despite that no longer being the case; he pottered about the house, smiled and patted us on the head, as though bestowing his approval upon us.

When I was a little older, a letter arrived from Grandfather to Mum, my brothers and me. In it, he gave us all advice on which line of study each of us ought to pursue. I seem to remember that I was to be an engineer and that my two brothers should be a doctor and lawyer respectively, while my mother should train to be a nurse. These were, I am sure, meant as instructions, not suggestions.

Like most youngsters, I never stopped to ask why the world was as it was. Nobody we knew ate curry, nobody went to London. Yet it never occurred to me that we were very different than anybody else. I knew that my skin made me stand out, but never felt it had bearing on who I was, or that this difference might have an actual name. But when my brothers and I heard that the townsfolk of Porsgrunn poked fun at the people from the rural hamlet of Bamble, calling them Bamble-Indians, it gave us pause. We knew Mum had been born in Bamble, so we reasoned that if anybody could be true Bamble-Indians, it must be us. What was the alternative? Half-Indian? Was there such a word? And to add to the confusion, Dad had told us that we weren’t actually Indian, we were Goan. And from Africa. And that we were British. And Portuguese. And Norwegian. It was all too much for us to grasp, so Bamble-Indian seemed as good as anything.

The truth was, I wasn’t too bothered about my skin color as a child. Nor do I remember it bothering anyone else. The only exception being the time I got into a playground fight with Bønna. In the tense moment of silence when the last swearword had been spent and the fists were about to come out, he suddenly blurted out:

“Negro!”

Everybody froze. Looks darted across the circle that had gathered around us. Even Bønna looked shocked at his own flash of creativity. A split second later the first blow was struck. I believe it was mine.

Although the Norway in which I grew up was almost exclusively white, it wasn’t my color that troubled me, nor was it my weird first name or even weirder surname. No, the cross I had to bear was my middle name, Bjarne, given to me in honor of my Norwegian grandfather. Sadly, you’d be wrong to think I took the least pride in this name. It was embarrassingly old-fashioned. Whenever the teacher took the register I waited in terror for the sniggers to rise from the desks around me the moment the B-word was uttered. People do not fear the unknown, as we imagine, they fear what they think they know. My exotic otherness must have effected my classmate’s perception of me, but it was just that; vaguely exotic, indefinable. The name Bjarne, on the other hand, stood out like a sore thumb.

I can see all this now, but back then it hardly entered my mind. I was Norwegian. I was who I was. Why should there be any contradiction between my dark curls and the fact that I was called Bjarne?

What I understand now too, of course, is that even though Dad was Norwegian in my eyes, in his own eyes he was not. And thinking back now, I did have a sense of this even then. For example, when we went down to Steinvika for a swim. Dad didn’t behave like the other grown-ups. He didn’t walk calmly out to the water like Mum, he didn’t dive in with quiet dignity. Instead, he’d charge through the kids standing at the water’s edge, wade in and then plunge out onto his belly making the water splash over the shivering bodies all around him. I didn’t know then, and still don’t for sure, whether or not he could dive. He certainly hadn’t learned to swim until he was an adult, nor indeed had his siblings. They came from a paradise with warm beaches and crystal clear water. But swimming wasn’t something one did in Dad’s family. Grandmother didn’t allow it. She was determined to protect her kids from any danger.

The beach at Steinvika was just ten minutes away from our house in Langesund. It was generally only the four of us, Mum and we three boys, who would go there. Mum with a large, floral cool-bag containing her special ice-cold milk, made with a dash of vanilla essence and pink or green food coloring. Steinvika was our paradise, and the occasional times that Dad came with us were accompanied by a sense of embarrassment.

What is embarrassment? The painful feeling of something being exposed which ought to remain hidden. A tight knot that expands and unfurls as soon as it comes under other people’s gaze. Like a Chinese paper flower in water. Like my father on the shore, taking off his shirt and revealing his hairy chest. I don’t know how old I was when this sense of embarrassment was first triggered, but it must have been when I started to think that Dad wasn’t quite like other dads. Partly, I think it came from my growing awareness of his visibility. I pitied him simply for being who he was, a handsome man with brown skin and black, curly hair, among all those pasty nineteen-seventies Norwegian bodies. But it came perhaps even more from my being troubled by, yes, ashamed of him. Because if Dad felt his own differentness, he wasn’t the sort to hide away. On the contrary, it was as though he had to draw attention to himself; the way he took off his clothes, the way he turned the beach into his own personal stage, the path from the rug and cool-bag to the water’s edge into a victory run. It was I who wanted to hide him away. Only when he was submerged under water, could I exhale.

Dad took up a great deal of space. At home he filled the rooms with his presence, with his loud voice. Yet I have remarkably few memories of him. When I try to picture Dad and I together, playing a game, or rolling a ball between us, or him pulling a duvet over me, I generally have to give up. There are several photographs in the family album of me sitting on his lap laughing, with his arms around me. I look relaxed and safe, but I have no memory of the moment. Rather my memories of Dad are like physical sensations, impressions left on my body. And what my body remembers is at odds with what these pictures say.

The strong hands never gave; they took. Grandma once told me something strange she’d observed when she watched Dad play-fighting with us. “He never let you win”, she said. The game always ended with him pulling you down onto the floor, then going off to do grown-up things.” I can’t remember this, but as I try to picture the scene, the physical sensation of losing immediately hits me. Equally I relive the sense of unease that filled us whenever he entered a room; if he was happy, we had to be happy, if he was angry, we felt we’d done something wrong, although we rarely knew what.

“The weather’s so beautiful today,” he might suddenly declare at Sunday breakfast. “Let’s go to the park, and take the guitar. Oh, I’m happy, so happy!”

When we refused or suggested we had other plans, his mood would turn. What was wrong with us? Why did we want to ruin his day? It was as though he continually wanted something from us that we couldn’t quite grasp. And since we never got things right, and were never good enough, he was never satisfied. Whatever the case, his reproach and anger are what I remember most. The roars that issued from the living room; the fist slamming down on the table; the dancing milk glasses, the streams of milk running over the tablecloth. Why did he break things when he was crying?

Only as I got older did I consider that all Dad’s sadness, his anger, might be related to his sense of being a foreigner, a stranger in his own home. “Why can’t we be like a real family?” he would say, his voice filled with bitterness and reproach. “Why won’t you answer me in English?”

And why didn’t we want to sing together, or pray together? Like a real family. Was it his memory of the family of his own childhood that Dad was harping back to? The laughing uncles and beautiful sari-clad aunts certainly weren’t like him. They were warm and gentle. Dad demanded that we speak English, demanded that we sing and sit in the park together, demanded we be a happy family. We never knew quite what to say, but defended ourselves as best we could. In Norwegian. In a childhood otherwise filled with sun-baked rocks on Steinvik beach, wild snowball fights, play-fighting on the living room floor, rambling in the forest alone with a sketchbook or with my mother, Dad became an increasing irrelevance in my life. He was against us, and we were against him. We made detours around him to get peace. Useless, of course, since he was still there with his over-sized emotions. Were we the cause of all this nastiness? Or was Mum? Eventually I realized it was something else. Something he carried within him from his own childhood. His own projection of the family we never were for him. That we didn’t want to be. Or was there something he’d lost along the way, a loss that had left him with an insatiable desire, a restless anger that could descend on him at any time or place? At home, or in the car. Yes, especially in the car; the abrupt swerving, the roar of the accelerator, the aggression that transmitted itself through his arms to the steering wheel and into the heavy bodywork, the entire car becoming a vibrating metallic membrane for all the rage inside him. While I clung tightly to the driver’s seat in front of me.

“Don’t swerve so much, Dad, please don’t swerve like that!”

The older I got, the more I questioned these things. Slowly but surely, I realized that my world was not the same as his, and that the answer to why Dad was who he was, lay somewhere far beyond my own horizon.

WHERE DOES DAD’S STORY BEGIN? Where does mine begin? The truth is that no story has an absolute beginning; all we can do is clutch randomly at the tangle of threads that lead from ourselves and back in time, generation upon generation, until they vanish into the vast darkness from which we all once issued. I scan the oldest photograph I’ve found in the family albums and open it on my Mac. The image is from the funeral card of my Dad’s grandfather, my great grandfather, Aleixo Mariano de Figueiredo. He died in 1940 aged sixty-eight, but the portrait shows him in his prime; a slim, handsome man, with a moustache and wavy hair. Pinned proudly on his lapel is the medal he’d been awarded for his lifelong service as postmaster to the Sultan of Zanzibar. Order of the Brilliant Star. Those who remember him describe him as a stern man who rarely smiled, a strong, determined character with European manners. Apparently he had Dad’s dark eyes, though it’s impossible to tell from the image of the old crumpled photograph on my screen, in which his eyes melt into a haze of zigzag pixels. I zoom in, trying to capture his gaze. But the more the image fills the screen, the more the shadow over his eyes melts into the grey background.

It is as if Great Grandfather is struggling to emerge from a darkness that refuses to release him. All I know of his origins is that he was born in Goa in 1872, in the village of Saligão, close to Calangute beach. There he built a house for himself and his mother, Maria Santana, but I know even less about her, apart from the story of how she got her nickname. It’s said that Maria had lent some money to a crook who never paid her back. Time after time she walked through the village to demand he repay her, and each time she returned empty-handed. Everyone in the village knew about it, and when her trips back and forth became a daily occurrence, they started to tease her:

“Where are you going today, Maria?” they asked.

Maria would simply answer “Zatã, Zatã”, which in Konkani means, “It will happen.” Which is how my great-great-grandmother got her name Maria Santana Zatã. To this day people in Saligão tell each other this story, laughing and slapping their thighs. Because the village never forgets anything; not Maria Zatã, nor the son who left, nor his descendants, nor even those of us who’ve never set foot in Saligão.

The house Aleixo built was on a hillside in the area of the village of Salmona. A traditional Portuguese-Goan house, whitewashed with tall, elongated windows, whose panes were made of translucent layers of oyster shell that let a soft glimmering light into the rooms. A wide set of steps led up to the front door and to a shaded porch which ran along the entire front of the house. It was a handsome house, even though many of the floors were made of stamped down cow dung. The largest room however must have had tiled floor, since the family apparently held balls and other social events there for the village’s beau monde.

Saligão was a typical Goan village, its houses clustered around a patchwork of paddy fields cut through by roads and rows of coconut palms. To the north of the paddy fields rose the neo-Gothic style church, Mãe de Deus, built in the year after Aleixo’s birth. The entire village would have been visible from its gleaming white tower, were it not for the fact that most of the houses lay hidden in the shade of banana trees, jackfruit trees and other vegetation. It must have been a vision of tranquility; life in Saligão was allowed to unfold at its own pace, interrupted only by the Angelus bells calling the villagers to prayer at dawn, noon and lastly at sunset. It was then that families gathered after a long day in the paddy fields, and in the light of their kerosene lamps knelt down on the ground, turned toward the village church and recited the Angelus prayer. At eight in the evening they got out their rosaries, ate dinner and went to bed. Night followed, coal black, apart from the occasional dim light from a coconut lantern carried by a solitary night-wanderer.

Peace reigned over Saligão. As it had for centuries. Ever since the 20th of May in 1498 when Vasco da Gama dropped anchor outside Calicut. The first day in the creation of our clan.

Vasco da Gama had discovered the sea route from Europe to India by sailing around the southern tip of Africa. Since time immemorial the Arabs, Gujarati, Ottomans, Venetians, Chinese and others had sailed the Indian Ocean assisted by the monsoon winds, their ships loaded high with merchandise. But the Portuguese wanted the lucrative spice trade to themselves, and to strengthen their monopoly they levied taxes on their competitors, or simply blasted them to bits with their superior weapons and ships. In return the Portuguese shared Christianity’s joyous message with the local heathens. The Portuguese wanted souls and sea routes, not land. But seas cannot be conquered without securing strategic ports and coastline fortifications. And it was Goa, the little enclave north of Calicut which had until then been under the sole rule of the sultan of Bijapur, which was chosen as the stronghold for the Portuguese. Which explains why Catholicism and spices would become the prime ingredients of my ancestors’ existence.

In the decade following da Gama’s discovery, Portugal’s King Manuel I sent ship after ship to conquer Goa, managing eventually in 1510 to bring the territory between the Mandovi and Zuari rivers under Portuguese rule. These districts became the heart of the Portuguese colony of Goa, known as Velhas Conquistas, the Old Conquests. Over the next centuries the Portuguese took more surrounding districts, Novas Conquistas, the New Conquests, as well as the Diu and Daman enclaves.

The town of Goa, situated some distance up the Mandovi River, became the capital of the entire Portuguese Indian Empire. In just a few decades, the town grew in population and splendor, becoming a metropolis inhabited by Muslims, Christians and Hindus, and even a Jewish minority. Magnificent late renaissance and baroque churches and elegant Portuguese villas shot up between the river and the jungle. And the streets and bazaars streamed with soldiers, traders, prostitutes, the occasional wealthy Portuguese family beneath large parasols, surrounded by servants and African slaves. This isn’t to forget the priests. After the arrival of various Catholic orders in town, you were likely to bump into an ecclesiastical habit at every other corner. The Franciscans and Jesuits christianized the town by the sword and threats, and before long Goa was transformed into the Rome of the East, the Asian center of Christianity. Not that all the natives were willing to give up their Hindu faith in favor of Catholicism, far from it, but those who did took the names of saints, and Portuguese heroes and nobles.

Many Goan families thus mirrored the ancient ancestral lines of Portugal. Names like Mendes, Almeida, De Souza, Paes and Constantino, later Noronha, Pinto and de Figueiredo, lived on among Indians who cast aside their ancient faith and donned western clothes. These new converts, however, hung onto their old cooking pots and added their own ingredients to the Portuguese dishes they now adopted.

I look at the photograph of Aleixo; so stiff and formal in his white shirt and black waistcoat under his dark grey jacket. The medal, the bowtie, the high collar. And beneath it all, his brown body, which was markedly light, a feature much valued among the Goans. An Indian in a suit, Aleixo was a descendent of converts from the highest caste – the Brahmins, who, for generations, had adopted as much European culture as the Portuguese chose to share with them – a creole people, shaped not only by the meeting between Portugal and India, but also by what the Portuguese brought from their vast territories that stretched from Brazil to China. Aleixo’s people, Dad’s people, my ancestors, were a new, yet simultaneously ancient people.

And, one might add, an “unclean” people, in the view of others, at least. How else could you describe a Catholic Brahmin who drank alcohol and ate beef, and who not only adopted a European fondness for pork, but built a hatch behind his toilet where the pigs could feed, before being eaten by human beings – a lifecycle in its crudest form. The Portuguese and converted Goans were the only people who did not observe the laws of cleanliness that were otherwise prevalent in Indian culture; Catholics ate anything and everything. In the towns and villages around Goa, the Catholic Goans lived much as they always had, but now they lived in whitewashed houses with awnings over cool terraces, decorative oyster-shell windows, and azure or sea-green shutters; a sight that for any Western visitor must have conjured thoughts of the Mediterranean, rather than India. Where others saw an unclean people, the Goans donned their Sunday best each week – the men clean-shaven and in suits, the women in white dresses – and walked to church along the road between rice fields and coconut palms.

And the centuries ticked by.

Eventually as new powers took control in the Indian Ocean, the power of the Portuguese came under threat. The Dutch arrived first, then the mighty British Empire laid its milky-white hand over large parts of Asia and Africa. But with the exception of a short-lived British occupation in the early 1800s, the Portuguese maintained control, but their decline was already written on the wall. In 1775 malaria and cholera epidemics in the capital had forced the governing powers to evacuate their people to Panjim at the mouth of the Mandovi River. Once Asia’s center of Christianity, the now abandoned city would become known as Velha Goa, Old Goa. The jungle threatened to invade its cathedrals and grand villas. A sweet slumber settled over the country. No significant modernization took place; any industry was modest. There was little for future generations to hope for. The better-off still managed to live a comfortable life in their spacious houses and secure government posts; they spoke Portuguese and sent their sons to the best university in Lisbon. Anyone else was left to wade ankle-deep in the paddy fields. The only alternative was to emigrate.

Some time at the end of the 19th century Aleixo must have made a decision. He’d recently married a village girl, Ermelinda Fernandez, and if they were going to forge a future together, they had to leave their homeland. They boarded the steamboat in Panjim that sailed along the coastline before heading north to Bombay. Great Grandfather must have been about twenty-five, Great Grandmother eight years younger.

Doubtless they weren’t the only ones on that boat from their village. From their region alone, that of Bardez, nearly a quarter of the population would leave, most of them Catholics, and many of them Brahmins. They were among the village elite. And not only that, but the colonists had instilled them with the Portuguese culture and way of life, and tempted them with ambitions for a future that far exceeded anything that Goa might offer. What could be more natural than to emigrate, especially when the Portuguese were encouraging them to leave and administrate colonies elsewhere in the world.

They were not refugees. They were not escaping a disaster zone. They were leaving to improve their lives. To climb up, rather than to sink. To live, rather than to merely survive.

In Bombay, Aleixo and Ermelinda probably stayed in one of the Goan hostels that were found throughout the city at the time. Here they probably enjoyed a final moment of village camaraderie before their journey continued over the ocean. While some emigrants traveled to Portuguese Africa, Angola and Mozambique, others headed for the new imperial power, Britain, and its colonies and protectorates on the same continent. Like so many other emigrants, Aleixo and Ermelinda headed for Zanzibar. Unlike most others, however, they did not settle here, but continued on to the small, lush-green island of Pemba about ten miles north of the mother-island Zanzibar. The island had become a British protectorate some years earlier, so when Aleixo was made postmaster in the modest cluster of buildings that constituted Pemba’s capital Chake Chake, he indirectly became a subject of the British Empire.

My family’s fate was cast.

Aleixo and Ermelinda were the first in the family to break out of the cycle of rural life, leaving the only place to which they truly belonged, where their family had lived for so long in a harmonious pact with their forebears, the earth, the church and Portugal. Everything that had been woven together over centuries was about to be ripped apart. Aleixo left the sleepy Portuguese empire for a defeated Arab sultanate where he would serve the British Empire that would itself only survive him by a few years. Toward the end of his life Aleixo would return to Saligão – the ties of origin are not broken in the span of one man’s life. But for those who followed, the circle had been broken, and homelessness was the inheritance they were left by Aleixo. He had been the first to leave his homeland, and he was the last to return. It is here, with Great Grandfather, that my family’s journey through the era of dying empires begins.