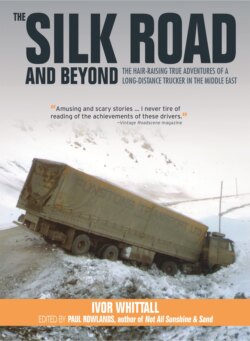

Читать книгу The Silk Road and Beyond - Ivor Whitall - Страница 14

chapter nine TURKEY, ANOTHER WORLD

ОглавлениеBlimey, it’s 9am. How tired were we? Thirteen hours sleep, I’ve never had 13 hours sleep in my life before! There was no movement from the others, so it was kettle on for a teeth-cleaning brew. Taking one round to the lads, it was decided, well Morrie decided, to have a gentle run down to the Mocamp and spend the rest of the day relaxing round the pool. That was fine by me. A few hours to relax and gather my thoughts was an excellent idea, and by a pool!

It was a fine sunny spring morning as we pulled out onto the highway and headed expectantly for Istanbul. My first impression of this ancient, culturally rich country was distinctly disappointing. Poverty appeared to be the order of the day and it seemed as if we’d been transported back a few 100 years, to a time of fiefdom. Nothing was tended or cared for and nature appeared to be left to its own devices. The road, though black tarmac, wasn’t much better than that in Yugoslavia. This was a trip that was certainly going to test how well the young DAF and me were screwed together. From where we’d parked it was only a 200 km run down to Istanbul and my early impressions of neglect were more or less confirmed as we passed through numerous small townships that, though bustling and lively, looked dilapidated and run down.

“Poverty appeared to be the order of the day and it seemed as if we’d been transported back a few 100 years, to a time of fiefdom.”

As we climbed the long, steep Silivri hill and dropped down the far side onto the coast of the Sea of Marmaris, we finally joined one of the long urbanised tentacles that lead eventually to the city itself. All along this coastal strip appeared to be a Turkish holiday resort as the sea front was lined with blocks of flats as far as the eye could see. We were getting close now. It was no more than 10 minutes away.

And there it was! A large scripted sign, Londra Camping. Probably the most iconic name on the Middle East run. Pulling into the dusty old TIR park, full of trucks from every corner of Europe and beyond, I was looking forward to a bit of relaxation round this pool Morrie had spoken about and, stuffing a towel, wash gear and some clean clothes into my duffle bag, I walked with the lads round to the motel reception to meet the manager, Mustafa. On the ‘camp’ side of campsite, he took our money, allocated us a room and pointed out the benefits of the place, with surprisingly, no mention of the pool. The shower wasn’t the best I’d ever had, but at least it was warm, as I luxuriated in it for a good half an hour. It’s amazing how much grime and unpleasantness one’s body can accumulate in four days of driving! Meeting the others, who were already wandering around the shop admiring the leather jackets, jerkins and hats, we headed for the restaurant, passing by a large sunken concrete receptacle that was full of a green algaecovered liquid.

“It looks like a breeding ground for mosquitoes!”

‘Strange place to have a cesspit,’ I commented. ‘Mind you, I suppose this is Turkey.’

‘Ah,’ smirked Morrie. ‘You know that pool you were so looking forward to relaxing by, well get your deckchair out Ivor!’

‘You’re joking!’ I said, trying to hold back a queasy feeling in my stomach. ‘It looks like a breeding ground for mosquitoes!’

I wanted to try real Turkish food, however it seemed as if this restaurant only catered for West Europeans and assumed we all ate bifstek, egg and chips. The ‘fried’ eggs looked as if they’d been wafted over the frying pan rather than dropped in it, and the ‘chips’ looked as if they’d been boiled! It all looked pretty gruesome.

‘Fancy an evening in the club, lads,’ asked Morrie, ‘and maybe a wander across to the West Berlin after?’

‘Why not,’ said Taff. ‘Woss the West Berlin then?’

‘Just a local night club,’ he smiled.

To call the Mocamp nightclub’s activities ‘entertainment’ would be to destroy the credibility of the word! Even amateurish would be stretching the imagination. A magnificently statuesque lady performed the dance of the seven veils to the best of her ability while encouraging us to slip money into her waistband, the norm for this dance in Turkey, apparently. She was immediately followed by a local city band, who had evidently never learned English, and who performed possibly the worst cover version of The Beatles’ ‘She Loves You’ that I’d ever heard!

‘C’mon, let’s go across the road to the club we were talking about earlier,’ said Morrie, getting up mid-song. ‘They’re murdering this.’

A scramble across the central reservation saw us knocking on the door of the West Berlin and we were ushered enthusiastically inside and upstairs to a table in the main room. By now there were five of us as two other first trippers, Phil and Bert, had joined our little throng to see what all the fuss was about. No sooner had we sat down than there were five Efes beers planted in front of us, rapidly followed by three young ladies who were obviously looking for business, gesturing to rooms at the back, while sipping our beer. Realising we were ‘shy’, one of the girls asked me why we weren’t interested.

‘But I have a beautiful wife and children at home,’ I responded.

It turned out we all had beautiful wives and children at home! Fast losing interest as they could see no financial activity taking place any time soon, they transferred their attention to a group of Swedish lads that had just turned up. Hah, blond haired and blue eyed, no contest really!

Sitting and watching the antics of the girls and their potential clients found us at well past midnight definitely inebriated, and not going to make that early start we promised ourselves.

I have no recollection of how we made it back across that the central reservation, or of getting into my cab, but somehow it seems I did.

I haven’t the foggiest how this happened, but without a thick head or the use of my alarm, at eight thirty I was awake and raring to go. This obviously didn’t apply to the others as a knock on their doors only received verbal abuse in response.

Phoning Billy to update him and find out what had happened to Damien proved a total waste of time. Having booked a call and being told I would be connected in 2 hours, when the time came it was impossible to hold a conversation due to interference on the line!

By ten thirty we’d finally got our ramshackle crew together and were driving over that wonderful feat of engineering, the Bosphorus Bridge. Here two worlds met, ancient and modern, as we crossed from Europe into Asia.

Approaching Gebze, a flashing headlight in my mirror caught my eye, and pulling over, Taff jumped out.

‘Think you’ve gorra puncher, boyo.’

Damn! Still, it wasn’t totally flat and in half an hour, sweating like a choir boy in a sex shop, we’d got the wheel off. Uncoupling the unit, we went looking for a tyre repair business, eventually ending up outside a dilapidated old shed with a huge Pirelli sign advertising his wares. His stock of tyres was a bit dubious, to say the least. I counted three that had got pieces of old tyre bolted onto the side walls! Had he got a spare tube?

“I haven’t the foggiest how this happened, but without a thick head or the use of my alarm, at eight thirty I was awake and raring to go.”

‘Hayir (no),’ said with a clicking noise from his tongue.

Blast, that meant I’d have to use the spare off my unit and try and get this repaired at a later date.

So it was back to the trailer and another hour before we were ready to continue our journey.

Crossing the Bosphorus was where we saw the start of real poverty. Derelict roadside properties sat alongside partially completed concrete structures. Kids were dressed in clothes that must have been passed down for generations, and packs of scrawny dogs snuffled around among the rubbish and dirt. This was a country where the people who inhabited this harsh rural landscape had a hard life, tending flocks of goats and growing what they could in the arid moonlike landscape. They looked grim-faced and careworn; you got the impression that, here, you fended for yourself or died.

Through Düzce, we started the long 6000 ft ascent over Bolu. The DAF was really earning her corn now as, with 20 tons on board, I was right down the box, second high or third low at best, and 10 to 15 mph if I was lucky. Even at not much more than walking pace we were still overtaking the local hauliers in their ‘Tonkas’. We thought we were slow. For them, it’s crawler and 3 to 4 mph maximum, taking the best part of a day to climb and descend this guardian to the Anatolian plateau.

Our colloquial name for the mainstay of the Turkish transport industry, Tonkas are normally four and six-wheel Ford, MAN and Desoto rigids that are usually fitted with ‘greedy boards’. Nearly always overloaded and overweight, they are the lifeblood of the Turkish economy!

“It must be me, I’m invariably the first to get up, I don’t know why.”

Dusk was settling over us as we made the slow descent down the far side and I was a little anxious about driving in the dark after all the horror stories I’d heard, but by eleven all five of us were safely ensconced on the forecourt of a Shell station on the outskirts of Ankara. We all topped up with diesel, which more than pleased the garage owner, who reciprocated with free chi all round.

As it was late, tonight’s speciality was going to be the ubiquitous ‘truckers stew’, the recipe of which varied from driver to driver and usually depended on what was available. Tonight’s effort consisted of beans, peas, luncheon meat, chicken curry, beef curry, Irish stew, carrots, and oxtail soup, all thickened up with a generous helping of instant mash powder and cooked in two saucepans. Eat your heart out Robert Carrier!

It must be me, I’m invariably the first to get up, I don’t know why. I always feel as if I’ve got to be doing something, and lying in isn’t doing anything. It was seven o’clock and the sun was already making inroads into the day, and I could tell it’s going to be a hot one.

Collecting four steaming cups of chi from the garage owner, I knocked the lads up, grumpy, ungrateful toe rags they were as well.

‘I know it’s you Ivor. Give us a break, for crying out loud,’ moaned Taff. ‘Bloody hell man, it’s only seven o’clock.’

Offering to pay for the tea, our new-found friend wouldn’t hear of it, but in Turkey, there’s always an alternative form of payment . . . Western cigarettes. Most Turks can’t afford them and usually smoke something called Bafra, and at 2p for ten you can imagine the quality. It’s almost like compacted straw, with a hint that that straw might have been involved in a rumination process first! A packet of Marlboro was always going to put you in a good light.

1975. Up in the Taurus mountains of southern Turkey heading for Adana on the way to Saudi Arabia. Once again, well over 6000-ft high and having yet another brew before the challenging 40-mile descent to the Mediterranean coast.

Diverted off-road at Nusaybin, Turkey, destination Baghdad.

1975. South of Aksaray, again aiming for Baghdad, with the Taurus mountains looming in the distance. Believe it or not, this was the main road to Saudi Arabia and most of the other Gulf countries!

By nine o’clock I’d managed to corral everyone and the five of us were on our way south to Adana, 300 miles distant. The road was not too bad, but with a well gritted and patchy tarmac surface, it was never going to be smooth. Going to have to wait till we’re in Saudi and the ‘Tapline’ for that luxury.

This is an arid dry landscape and generally speaking the vegetation, unless alongside a stream or river, looks sparse and threadbare. We were crossing the vast elevated plain of Central Anatolia now. It’s part of the huge mountain, valley and plateaux monolith that make up the majority of the land mass in this part of Turkey and Iran. This run down to Adana, though about 2000 ft above sea level, is pretty flat, the real mountains are off to the west, with Tarsus in the south yet to come. The sun was really pushing out the heat and most probably nudging 85°F as we passed the salt marshes at the top end of Lake Tuz. A salt lake, it’s vast, well over half the size of Lancashire, and is what’s known as hypersaline, making it a good source of income for the regions inhabitants. At no more than 5 ft deep, it’s one of the shallowest lakes on earth.

“The road was not too bad, but with a well gritted and patchy tarmac surface, it was never going to be smooth.”

Pulling onto a hard-packed dirt area, backed by a building with a large Restoran sign on the roof, Morrie decided that as his stomach was rumbling, we were all hungry. Among the numerous Tonkas parked up, Taff spotted two artics with English registration plates. Mick and Don, the two drivers, were sitting quietly on their own when our overenthusiastic waiter dragged an extra table and chairs across, so us Ingilis could sit together! After slightly embarrassed introductions, it turned out this was their first trip as well. While the rest got to know each other over chilled Coke, me and Mick, who seemed to hit it off straight away, wandered over to the counter to see what food was available.

‘Blimey,’ I said, ‘I think that’s the same sort of meat I had in the Mocamp. Tasty it was, too.’

Mick didn’t know what to order as everything was in Turkish.

‘Tell you what,’ I said bravely, ‘let’s order seven of these with rice. I reckon most of us will like it, not sure about Bert though.’

And so it worked out; everyone thought it was delicious, except for Bert.

‘I’m not eating that muck,’ he moaned.

‘It’s not muck, you heathen, it’s really nice,’ encouraged Don. ‘What else you gonna eat then, how’s your Turkish?’

‘Eeeurgh,’ Bert responded squeamishly. ‘How can you eat that stuff? It’s been lying about, most probably covered in fly spit and who knows what. You’ll all die of food poisoning!’

‘Stop moaning Bert,’ scowled Morrie. ‘Fish and chips ain’t a local speciality round here. Tell you what mate, you’re gonna end up a lot slimmer when you get home if all you’re gonna do is complain about the grub. It’s a long time before we’re back in England. Go on give it a bloody try.’ With that, Bert picked up a lump of meat and gingerly chewed a bit off the end. He must have liked it, as within minutes he’d scoffed the lot; rice, vegetables and all. It’s amazing what a few hunger pangs can do!

‘I suppose it wasn’t too bad,’ he admitted, as we all lobbed bits of rice at him.

We’d now got a convoy of seven, with Morrie as our lead driver. His plan was to stop overnight at a town called Ceyhan, 25 miles the other side of Adana, but first we’d got to cross the Taurus mountain range that separates Anatolia from the Mediterranean. With the pass at around 7000 ft, it was going to be another long slow climb and it wasn’t much more than an hour before we could see the hazy outline of the mountains rising almost vertically out of the plateau in the distance. The closer we got, the taller and more formidable they looked, and this was taking into account we were already a good 2500 ft above sea level! As we passed through the village of Ulukişla, the road suddenly sharpened up and we were dropping right down the gearbox into a steady climb. The plateau we’d only recently left behind was rapidly shrinking into the distance below, giving us a spectacular view across the arid plain. This wasn’t a climb like Bolu, where the road was nice and wide. Nor was it like anything I’d ever come across back home. This was a road with millennia of history, a road that Paul of Tarsus might have walked 2000 years ago. It seemed to cling to the mountainside and was almost too narrow in places for trucks to safely pass. Other than the occasional marker post and tree holding on for dear life at the edge of the precipice, there was zero protection. The slightest error could easily end in disaster, and it was a very, very long way down!

The climb seemed never-ending and must have taken the best part of an hour and a half. Eventually we started to level out and pass the odd inhabited shack before entering the village of Pozanti. This is a place I definitely wouldn’t want to live. I mean, the village butcher was an open roadside stall, with meat hanging out for the passing trade. Can you imagine what that would be like with your two veg? The flavouring coming from the constant flow of heavy vehicles exhausting their diesel and petrol fumes, combined with the incessant dust and added fly flavour; that’s going to have a very individual taste!

“The climb seemed never-ending and must have taken the best part of an hour and a half.”

The drop down the other side took even longer. It’s a 70 km continual descent and with a heavy load, and drum brakes, too much braking would see the shoes glazed in next to no time. I was learning a whole new driving strategy on how to negotiate real mountains. Not a trip up Shap, however difficult that might be. This driving was so different to anything I could relate to. Low gear, frequent use of the feeble exhaust brake plus judicious use of the foot brake finally saw me down to the main east–west route along the Mediterranean coast.

The city of Adana, on the edge of the Seyhan Dam, was like a Turkish version of the Wild West. I was half expecting a Santa Fe stagecoach to appear out of the gloom. What with the Americans running the nearby NATO base, it was a bit of a ‘rocking’ town. Muddy, potholed roads and the typical carefree attitude of Turkish drivers just added to the mix. Within the hour we were parked up on a rough patch of ground near Ceyhan.

“BANG, BANG, BANG, on the door. I was absolutely sound, but this was serious banging”

Sadly for us it was our last night as a gang. Tomorrow would be saying goodbye to Morrie, as he was off to Baghdad, the rest of us to various destinations further south. Taffy had clutch problems but was going to try and soldier on to the Mercedes agent in Damascus.

BANG, BANG, BANG, on the door. I was absolutely sound asleep, but this was serious banging, as in a daze I reached over to pull back the curtain and see a Polis sign out of the side window. Mick was already out of his cab.

‘We’ve got to move,’ he shouted. ‘The cops say it’s not safe to stay here, apparently there’s a restaurant about three Ks up the road.’

Bleary eyed, we followed the Polis car to his ‘safe’ parking area and almost before I could switch the engine off I was straight back onto the bunk.

Next thing I knew, it was daylight and Morrie was up and about, knocking on our cabs to say goodbye. He was off to Zakho and wanted to get through the border by tonight. I was more than grateful for his help and patience, and it had been a good week running together; hopefully we’d meet up again.

The rest of us decided to make a move as well and headed off towards Toprakkale, only for Bert to realise that now he’d got a slow puncture. As he was only carrying a boy’s load, about 6 tons, we topped up the air with a line stretched from the cab. If we could get to Iskenderun, maybe we could find a tyre repair shop.

On the southern outskirts of the town, there it was; the ubiquitous roadside shack that could repair anything you’d care to present them with. Not only did they repair his inner tube, but my own as well. I’m convinced that had they got a rubber tree they would have had a bash at making their own tyres! Watching these guys work, using the most basic of tools, was an eye-opener. They were so talented and inventive, they put our efforts to shame.

Now we were getting close to the border, I was starting to get concerned about an agent. There wasn’t one listed in my folder for Cilvegözü. The other guys said the same, we’d have to wait and see.

This couldn’t be it, could it! We were on a narrow country road, hardly wide enough for two vehicles to pass, and there ahead of us was a flimsy red and white barrier with an empty sentry box. Parking, we walked across the road to what appeared to be a temporary restaurant with a lean-to alongside. Glancing through the doorway, there was a uniformed officer sat at a desk. This appeared to be the customs post! Kapikule this most definitely wasn’t . . .

Beckoning us in, he asked for our papers, saying in broken English. ‘Halluf one hower finis.’

‘Yeah, right,’ whispered Bert, ‘and pigs might fly,’ making a snorting sound.

True to his word, in halluf one hower it was finis; there was our passport and paperwork on the desk, all stamped and signed.

‘Today as is spezzial holiday, is 200TL,’ he said, handing them back with a smile.

Ah, the land of baksheesh, a spezzial holiday indeed, and I’ll bet there’s no receipt! I’ve become a cynic already, still it’s a small price to pay for such prompt service and not a bad little earner for him! He checked each face against the passport photo and, picking up Bert’s, added a snorting sound of his own. I’ve never seen anyone colour up so quickly! The barrier lifted and we were through into no-man’s-land.

A 2 km drive under a ruined arch to ‘The Gates of the Wind’, Bab al-Hawa, and we were at the border with Syria. Our load carnets were not accepted as valid documentation here and I’m not sure whether it’s because Syria wasn’t party to the international TIR accord, or because it was still regarded as a ‘war zone’. Whatever the reason, all documents had to be translated into Arabic by our agent and transit duty paid as a percentage of the load’s value; in my case the equivalent of £100 in Syrian Pounds! Only then was temporary transit paperwork issued, which had to be handed in when exiting the country. One thing you rapidly learned was patience. There seemed to be no accounting for the length of time clearances took. I mean, it was half an hour back there at Cilvegözü, but here it was going to be a very long time. A meal and a few cold drinks in the restaurant had us all feeling maudlin and by the time we’d got our translated documents back it was too late to go anywhere. Oh well, it was an early night with Radio Luxembourg to lull me to sleep.

“One thing you rapidly learned was patience. There seemed to be no accounting for the length of time clearances took.”

With another sunbaked day in prospect, our convoy was back on the road at 7.30am, heading for Damascus. As we headed further south, the landscape, though not what you’d call proper desert, was becoming more and more devoid of vegetation. Here the soil had a deep red orange timbre and didn’t look too rich in nutrients. I couldn’t imagine crops being a very productive source of food in this hostile environment.

I’ve no idea why I stopped with the others in Damascus; they had business there, I didn’t. It’s strange isn’t it. Maybe it’s the human psyche. Some of us had been travelling together for over a week and formed a bond, so it felt quite normal that if one of the guys had to stop and do something, we all stopped. I’ve since realised this was a type of first trip nerves, where safety in numbers was the order of the day. Morrie was right; get up, shake hands and say goodbye!

Not getting any response from Mick or Bert in the morning, I left a message on their windscreens and headed out of town, glad to get away from the abysmal standard of driving displayed by the local residents. If this is what we’d have to put up with in this dusty and fly-infested part of the world, I’d better keep a weather eye out for myself. Daraa, Syria’s border crossing into Jordan, was about an hour down the road. Arriving into the bedlam of ancient battered old trucks, piled high with various types of fruit, I could see right away that driving here was definitely not a non-contact ‘sport’.

What a shambles! It was a case of everyone for themselves, as the idea of queuing was obviously alien to them. So with the thought that if you can’t beat them, join them, I eased my way forward, allowing no one to squeeze even a coat of paint into the gap between me and the vehicle in front. Allow one in and suddenly he had three mates that ‘needed’ to get in. After around 2 hours of verbal and physical ‘jousting’ with this herd of demented ex camel jockeys, I was finally near the front of the queue. Then, out of nowhere an ‘agent’, dressed in a white kaftan type of robe appeared by my door, asking for my papers. Who was he? I didn’t know him from Adam, but such was the chaotic situation going on around me, I passed them through the open window in total trustworthiness.

It was uncomfortably hot and I was starting to get a little concerned about my decision to hand over my passport and all my documents to a total stranger. Seriously contemplating going to look for him, there was a tap on the door. He was back, speaking in perfect BBC English.

‘When you return from Kuwait Mr Ivor, come to see me about the Arabic translation of your triptiques (carnet de passages), and I will complete your paperwork.’

“What a shambles! It was a case of everyone for themselves, as the idea of queuing was obviously alien to them.”

I certainly will, I thought, and with a ‘thank you’ I was off and heading across another stretch of no-man’s-land to Ramtha, the Jordanian border. Here I’d got a nominated agent, Mohammed el Katib, and finding his office, I was offered the prerequisite chi before he took my documents. He noted straight away that I’d not got a Saudi visa. ‘Now it is too late,’ he informed me. ‘It will all be completed in the morning.’

Outside, I slumped down against the concrete wall, rolled myself a perennial soother and took a deep drag. What the hell am I doing here? Perched against a grubby wall in the middle of nowhere. What a godforsaken place.

‘Hello mate.’

I looked up.

‘You in this afternoon’s convoy?’ he asked.

‘What!’ I exhaled sharply. ‘What convoy? What you on about mate?’

‘Ah, first trip eh?’ he smiled. ‘It’s the convoy to H4. There are two a day, morning and afternoon. Look, I’ll have to be off, mine’s due to leave shortly, check with your agent.’

With that he was gone, no name, just asking me about a convoy I’d never even heard about!

My God, this job was an opencast minefield of potential disasters waiting to trip you up. There was nothing to be done now. I decided I’d do as he suggested and ask the agent in the morning. Sitting in the afternoon sun, I slowly cooked as I watched it drift across the cloudless sky. Other than the border post, agents’ offices and ‘toilets’, there was nothing else here.

Ah, toilet. Two syllables that are understood the world over as providing sanctuary for man in his time of need. For us long-haul truck drivers, the usual means of evacuating our souls was to bop down between the front and rear axles of our trailer, and after seeing the disgusting horror that entertained the name ‘toilet’ here, I wish I’d done just that! It abused the word in all respects. My one serious attempt at hoping it would fulfil its design function was rebuffed when I strolled across, book in hand, hoping to relax and pass the time of day communing with nature, to be met with an ancient chipped bit of Arabic style porcelain that had an absolute Ben Nevis of multi-coloured turds protruding from its innards. Even the plague of flies attending it couldn’t make any inroads. Retching heavily, I made a rapid retreat, only to watch as other men happily sauntered in and out.

“It was time to put the kettle on and roll a ciggie. I might as well boil my brains in the unrelenting heat.”

It was time to put the kettle on and roll a ciggie. I might as well boil my brains in the unrelenting heat.

‘Hello Ivor, thought you’d be long gone,’ said Mick, as he and Bert strolled around the front of the cab.

My spirits were lifted immediately.

‘Am I pleased to see you two,’ I laughed. ‘Aye, I thought I’d be long gone as well Mick, death by boredom was about to overcome me. I can’t get my visa till the morning, then apparently I’ve got to go in a convoy to H4. Luckily some bloke told me! Anyway, where’re the rest of the guys?’

‘Well you know that Taff’s getting his clutch replaced,’ said Bert. ‘The other two had paperwork problems with Sammi Sarissi. We overslept, which is why we’re late.’

‘Well you’d best get your papers in before 9am Bert, otherwise you’ll lose another day. At least you’ll have a chance at the afternoon convoy. Here, have a cuppa.’

‘You do know you can pick up Radio Luxembourg down here,’ said Mick, trying to block out the incessant dirge of a Jordanian driver playing ‘The Arabic Top Ten’. ‘I can’t stand the tuneless stuff they play here.’

‘Can you?’ I said, twiddling with the knob on the radio. ‘I could pick it up further north.’

Settling the dial onto a fuzzy sounding 208 was still a huge improvement on Mustafa’s ‘music’.

‘Look at the size of that,’ I said, watching in amazement as the biggest sun I’ve ever seen sank slowly over the horizon.

‘Aye,’ said Mick, ‘it’s something to do with the dust in the atmosphere, makes it shimmer and look bigger, or something like that.’

Sitting on the kerb, we talked well into the night about everything lorry, but it wasn’t like sitting in a British transport café moaning about roadworks, car drivers, weather, transport managers or the ministry. Oh no, that was mundane stuff. This was adventure on the hoof. Everything was new and had no parallel in the UK. I mean, tomorrow we were being convoyed to H4, whatever that was, and from there to the Saudi Arabian border was 70 miles of open desert, no road, just desert! How would that little nugget go down at Kate’s Cabin on the A1!