Читать книгу 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro with Complete Proof - J. A. Rogers - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJ.A. Rogers was born on September 6, 1880 in Negril, Parish Westmoreland, Jamaica, British West Indies to Samuel Rogers, a school teacher and Methodist minister, and Emily Johnstone. Emily bore Samuel four children, Joel Augustus, Martin, Ivy and Oswald. When I once asked him, where he got the name Joel, his answer was: “Simple, Joel was Samuel’s first son in the Old Testament.” Joel’s mother died in 1886 in Buff Bay, of dysentery, about a month after the birth of Oswald. A grieving widower, “crying and all broken up” Samuel soon moved to St. Ann’s Bay, where he met and courted his second wife, who bore him another seven children, the first one born in May 1888. In the meantime, Ivy, born in 1884, was sent to live with her maternal grandmother, who had a girls’ school in Savanna-La-Mar. Ivy did not cherish that experience, remembering her grandmother as stern and very hard on her. Samuel moved from school to school, always trying to better his financial situation. In the end, he became the manager of a large plantation, Stetten. When we were in Jamaica in 1965, Joel remembered the location exactly, recognizing the roads leading to it, but the estate itself was gone. Joel remembered his stepmother not unkindly. He felt that she had treated her stepchildren well, “according to her lights”, but that “her love was for her own children” and Joel and his brother Martin were none too pleased when they saw her pregnant again and again—“now, there will be even less affection for us.” The problem, the way Joel saw it, was with his father, who was excessively stern with the boys, down to the youngest, Ian, born in 1900, while the girls remembered a different side of their father.

Anyway, his father had an education, as had his uncle Henry, a surveyor, while with eleven children, all Samuel could do for his own children was to be sure they had a good basic education. Joel never forgave him for that, nor that he did not give him much guidance. However his uncle Henry had a large library and Joel read, and read, and read.

After failing to get a scholarship for college, Joel joined the British Army and served with the Royal Garrison Artillery at Port Royal. When his unit was about to be transferred abroad, a medical examination revealed a heart murmur, and Joel was considered unfit for foreign service. By chance he met a friend in Kingston, who told him that his brother had emigrated to the United States and liked it there. Joel decided to go.

While the Jamaica of his day was quite color conscious, Joel did not think of himself in terms of color, but rather in terms of class. His father had not allowed him to play with the black children on the plantation; after all, he came from a family of status, light-skinned, with household help. It therefore came as a great shock when in the New York City of 1906 he was discriminated against in a Times Square greasy spoon. The rage and humiliation he must have felt were still evident as he retold the story throughout his life. He had a number of jobs in New York City—as a delivery man—and worked briefly in a bookstore in Montclair, NJ, where he was introduced as “our latest arrival from Cuba”—he was being passed as white since Jamaicans were considered, regardless of complexion, colored. (He did not like that and eventually went to Canada.) However, in the New York of 1906 he loved Coney Island, and in later years liked to go there at least once a year. He also enjoyed the cartoon, “The Katzenjammer Kids” which was popular at the time.

Joel went to Chicago, where he studied commercial art for nine years, supporting himself as a Pullman porter, only to discover that the only work open to him, even after getting “A-honorable mention” for his work, was as a housepainter. He remained a Pullman porter, which paid well, gave him the opportunity to visit the 48 states, and to meet many interesting people until he moved back to New York.

Some of his experiences as a Pullman porter were fictionalized in FROM “SUPERMAN” TO MAN. Although fictional, the historical facts are true. I have always felt that you hear his voice, meet the man, mentioning all the books he read, the authors, the art he saw. He had been reading all his life, had been deeply impressed by Dumas, by Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, by Plutarch’s Lives of Illustrious Greeks and Romans and had studied the works of Schopenhauer for ten years. He identified with Schopenhauer’s feeling that Human goodness consists of treating others with consideration, sympathy, and generosity, that goodness consists of treating the welfare and rights of others as important as one’s own rights.

Joel became a naturalized citizen in 1917 and published the first edition of FROM “SUPERMAN” TO MAN the same year. By that time he was serious about his mission, the research into the origins of the human race, had found out that to be accomplished you did not have to have to be “white” in the American definition of the word. Also, most importantly, that slavery was not an inherently black condition or fate, that slavery had been around throughout recorded history.

During his early years in the States, he helped several of his siblings with their passage to the States. He was friendly with all of them but one has to understand that he was a man with a mission, which they did not share. Their concerns in life were different from his. They had families, they had livings to make, lived in white neighborhoods and can certainly not be blamed if they were less than eager to listen to his latest findings in his research all the time. “Passing” or not had nothing to do with that, very much apart from the fact that in surroundings divorced from his research he question of his color or lack thereof did not enter either. However, having had the early experience of his father siring eleven children, and the emotional deprivation he felt, he was a confirmed bachelor for most of his life. Also, with the sheer volume of his work, his books, his pamphlets, his articles, the fact that he travelled so extensively and lived for long stretches at a time in Paris—there really was no room in his life for a wife for most of his life.

Joel moved to New York City in 1921, where he met George S. Schuyler, who became his lifelong friend. He began to write for all the important Negro publications of his day, i.e. The Messenger, The Pittsburgh Courier, The Amsterdam News—writing for the latter two until his death in 1966. He also met H.L. Mencken and wrote for American Mercury.

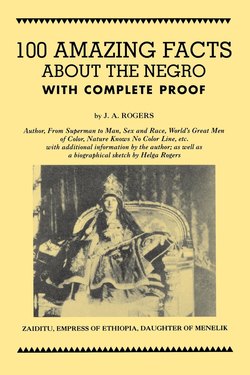

Even in the 1920’s, George Schuyler states in his book BLACK AND CONSERVATIVE that Joel had a tremendous knowledge of the historical background of the Negro and especially the miscegenation around the world. He took his first trip to Europe in 1925. He went to Paris, in 1927 to Germany, in 1928 to Egypt, in 1930 back to Paris and also to Ethiopia, where as a correspondent for The Amsterdam News he covered the coronation of Ras Tafari as he became the Emperor Haile Selassie. In 1935 he went back to Ethiopia to cover the Abyssinian War. Over the years, while retaining a residence in New York, with the exception of World War II, he made Paris his headquarters, doing his research from there, at the Biblioteque Nationale, at the British Museum in London, in Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Berlin, spending his time in museums, art galleries, antiquarian bookstores, churches. While in New York he went daily to the Rare Books Room in the NY Public Library.

Though Joel was an American citizen, he found life in Europe, especially in Paris, very congenial and gained recognition in France, as well as England early on. Recognition in the U.S. was much longer in coming and really quite spotty, though he did have his admirers, as I especially found out after his death. However, I never felt the recognition he had here was enough, considering the work he had done for others, helping to give them a leg up in the world and the intellectual wherewithal to do something with their lives. I always felt, and voiced it at the time, that had he used his brilliant mind and his dedication and tenacity for, say, cancer research, he would have had a Nobel Prize and the financial rewards, instead of the hand-to-mouth existence he lived most of his life, plus the lack of appreciation. While he did not disagree with my sentiments, he always felt that he would come into his own once he was gone, that he would be vindicated, which proved to be true. Anyway, he did what he wanted to do and lived the life he wanted to live, and he died a happy and fulfilled man.

He used his knowledge in his weekly columns in the Pittsburgh Courier, The Amsterdam News, The Chicago Defender and other publications. Thus he popularized Black history and he was recognized as an authority on the history of African people, on race and race relations. His columns on history were read by the general reader and were meant to give him a sense of self-worth and the feeling that he could become somebody in his own right and was not inferior to anyone. He fervently believed in the right to an equal chance at the starting gate of life, unencumbered with a sense of inferiority. He believed in one race, the human race, and that color was meaningless, and did not stand in the way of achievement. Thus “NATURE KNOWS NO COLOR LINE”.

He made the attempt to locate Africa’s proper place on the maps of human geography, he had found in his research that the Egypt of the pharaohs was not a White country by looking at Egyptian art. Egypt had a profound influence on Greece and not the other way around, that the White man’s civilization was only a continuation of African civilizations of antiquity—all findings that did not make him very popular, but that have been validated in the meantime.

Charles Darwin predicted that the deepest roots of human evolution would be found in Africa. Joel also came across Dr. L.S. B. Leakey’s research and find of fossils in the Olduvei Gorge in East Africa, proving that earliest man did indeed arise in Africa. Just recently a team of paleontologists from the University of California at Berkeley, led by Dr. Tim D. White, have broken a critical time barrier and found in Ethiopia the fossils of the oldest direct human ancestor, giving him the name Australopithecus ramidus.

As was generally the case, J. A. Rogers came across information, publicized it, was considered controversial and way off base in his statements and conclusions. Then subsequent research found him to be correct and could go beyond it, thereby validating it. Dr. Leslie C. Dunn of Columbia University, who was one of this country’s leading geneticists, disproved the notion that the contribution of each parent blends in the child. These studies also have destroyed the old “blood theory” and contradict former views of fixed and absolute biological differences among the races. Geographic isolation, migration of populations and especially, mutations of genes have created “subgroups”, Dr. Dunn argued, but these differences do not imply a basic difference of race. (The New York Times, 3/20/74)

Much was made in his Joel’s lifetime in the States, though not in Europe, where he was recognized early on, of the fact that he was not a man of academic letters. That very much misses the point. He was a man who had learned idiomatic German, French and Spanish, could do his research in all these languages besides English and speak the languages fluently. He did the leg work and knew what to look for in his research. To try to evaluate his contribution to anthropology, racial origins, historical research in the light of today’s basic academic requirements before anybody can get a foot in the door somewhere, is to look for Henry Ford’s degree in Engineering, John D. Rockefeller’s degree in Geology, etc. Advanced education was very rare at that time and that fact certainly neither stopped Henry Ford, nor Rockefeller, nor anybody else. Time marched on there, too, and today’s cars are as far removed from the early cars, oil drilling has evolved greatly, and so on.

In his research all over the world, by looking at the artifacts first-hand, he compiled a body of history as a pioneer, with all the glories and drawbacks of a pioneer, decades ahead of his time, a work that will stand as his monument and will have to be referred to in any U.S. teaching of “integrated” history, integrated in the proper meaning of the word, history taught in its proper perspective, without trying to gloss over historical facts for one reason or another.

In his book AFRICA’S GIFT TO AMERICA, Joel stated that more than one half the world’s cotton was grown by the Black man in the South by 1918. He perceived it as the Black man’s crop. Professor Robert W. Fogel, who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science for 1993 in Stockholm, wrote a book on slavery, “Time On The Cross”, in 1974, in which he argued that the owners of slaves looked upon slaves as economic assets and treated them as well as livestock, that slavery was an efficient system for growing cotton and that the system collapsed for political—not economic reasons (The New York Times, October 13, 1993).

As John H. Clarke stated in his introduction to WORLD’S GREAT MEN OF COLOR, Vol. I, “In biographical research Rogers journeyed further and accomplished more than any other writer before him.” Also, “in more than forty-five years of travel and research (two generations), he more than any other writer of his time, attempted to affirm the humanity of the African personality and to show the role that African people have played in the development of human history. This was singularly he major mission of his life, it was also the legacy that he left to his people and the world.”

As the New York Times Book Review of February 4, 1973, written by John Ralph Willis had it, in reviewing WORLD’S GREAT MEN OF COLOR, “Rogers’s reputation rests on two foundations. He brought African biography out of the backwater of world literature, and he removed the “Great Undiscussable” of sex-race as a formidable taboo for professional review.”

He did more than anyone else in the field, and had his writings been heeded, maybe we would not have the awful mess with our schools, with the inner cities.

He married when he thought that he had most of his work completed and, therefore, a free mind for yet another adventure, marriage. However, AFRICA’S GIFT TO AMERICA as well as THE FIVE NEGRO PRESIDENTS were written subsequently. Still, he put as much effort into being a lovely husband as he had previously put into his work. He had a stroke while in Washington, D.C., where we visited friends. We had spent all day at the National Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution, where he found interesting things for his new book. He planned to go back to the Library of Congress the next week, for further research on the OLMECS. While he had established long ago that there had been migration from Africa to South America around 500 A.D., again something only validated after his lifetime, which accounted for some of the physiogonomies he found on the monuments, he wanted to write in depth about the OLMECS...........

He died on March 26, 1966 in New York. His work is his own monument to a brilliant, committed, highly idealistic man. To quote him, “…do we consider a man great because of the degree to which his life and actions affected humanity?” (World’s Great Men of Color, Vol. I, How and Why This Book Was Written, p. 21). Using this criterion alone, he was a great man. Ave atque vale.

Helga Rogers

1995