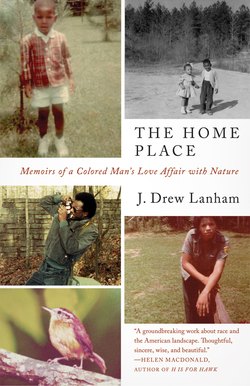

Читать книгу The Home Place - J. Drew Lanham - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMe: An Introduction

I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and incur my own abhorrence.

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

I AM A MAN IN LOVE WITH NATURE. I AM AN ECO-ADDICT, consuming everything that the outdoors offers in its all-you-can-sense, seasonal buffet. I am a wildling, born of forests and fields and more comfortable on unpaved back roads and winding woodland paths than in any place where concrete, asphalt, and crowds prevail. In my obsession I “celebrate myself, and sing myself,” living Walt Whitman’s exaltations, rolling and reveling in all that nature lays before me.

I am an ornithologist, wildlife ecologist, and college professor. I am a father, husband, son, and brother. I hope to some I am a friend. I bird. I hunt. I gather. I am a seeker and a noticer. I am a lover. My being finds its foundation in open places.

I’m a man of color—African American by politically correct convention—mostly black by virtue of ancestors who trod ground in central and west Africa before being brought to foreign shores. In me there’s additionally an inkling of Irish, a bit of Brit, a smidgen of Scandinavian, and some American Indian, Asian, and Neanderthal tossed in, too. But that’s only a part of the whole: There is also the red of miry clay, plowed up and planted to pass a legacy forward. There is the brown of spring floods rushing over a Savannah River shoal. There is the gold of ripening tobacco drying in the heat of summer’s last breath. There are endless rows of cotton’s cloudy white. My plumage is a kaleidoscopic rainbow of an eternal hope and the deepest blue of despair and darkness. All of these hues are me; I am, in the deepest sense, colored.

I am as much a scientist as I am a black man; my skin defines me no more than my heart does. But somehow my color often casts my love affair with nature in shadow. Being who and what I am doesn’t fit the common calculus. I am the rare bird, the oddity: appreciated by some for my different perspective and discounted by others as an unnecessary nuisance, an unusually colored fish out of water.

But in all my time wandering I’ve yet to have a wild creature question my identity. Not a single cardinal or ovenbird has ever paused in dawnsong declaration to ask the reason for my being. White-tailed deer seem just as put off by my hunter friend’s whiteness as they are by my blackness. Responses in forests and fields are not born of any preconceived notions of what “should be.” They lie only in the fact that I am.

Each of us is so much more than the pigment that orders us into convenient compartments of occupation, avocation, or behavior. It’s easy to default to expectation. But nature shows me a better, wilder way. I resist the easy path and claim the implausible, indecipherable, and unconventional.

What is wildness? To be wild is to be colorful, and in the claims of colorfulness there’s an embracing and a self-acceptance. We scientists are trained to be comfortable with the multiple questions that each new revelation may elicit. Like sweetgum trees, which find a way to survive in the face of every attempt to exclude them, the questions we ask are persistent resprouts, largely uncontrollable. There really aren’t hard-and-fast answers to most questions, though. Wildness means living in the unknown. Time is teaching me to extend the philosophies of science to life, to accept the mystery and embrace the next query as an opportunity for another quest.

I find solace, inspiration, and exhilaration in nature. Issues there are boiled down to the simplest imperative: survive. Sometimes my existence seems to hang in the balance of challenges professional and personal, external and internal. What allows me to survive day to day is having nature as my guide.

But I worry as the survival of many of the wild things and places themselves seems increasingly uncertain. Called by something deep inside, I have joined with kindred wandering-wondering watchers and ecologically enlightened spirits in the mission to keep things whole. After all my years of being the scientist–idea generator–objective data gatherer, I yearn for more than statistical explanations.

My colleagues and I have mostly done a poor job of reaching the hearts and minds of those who don’t hold advanced degrees with an “ology” at the end. We take a multidimensional array of creatures, places, and interwoven lives and boil them down into the flat pages and prose of obscure journals most will never read. Those tomes are important—but the sin is in leaving the words to die there, pressed between the pages. As knowledge molders in the stacks the public goes on largely uninformed about the wild beings and places that should matter to all of us.

Science’s tendency to make the miraculous mundane is like replacing the richest artistry with paint-by-number portraits. In the current climate of scientific sausage making—grinding data through complex statistical packages and then encasing it in a model that often has little chance of real-world implementation—we are losing touch. How inspiring is the output that prescribes some impossible task? How practical is it? We must rediscover the art in conservation and reorient toward doing and not talking.

What do I live for? I eventually realized that to make a difference I had to step outside, into creation, and refocus on the roots of my passion. If an ounce of soil, a sparrow, or an acre of forest is to remain then we must all push things forward. To save wildlife and wild places the traction has to come not from the regurgitation of bad-news data but from the poets, prophets, preachers, professors, and presidents who have always dared to inspire. Heart and mind cannot be exclusive of one another in the fight to save anything. To help others understand nature is to make it breathe like some giant: a revolving, evolving, celestial being with ecosystems acting as organs and the living things within those places—humans included—as cells vital to its survival. My hope is that somehow I might move others to find themselves magnified in nature, whomever and wherever they might be.

These chapters are a cataloging of some of the people, places, and things that have shaped me. They are patchwork pieces stitched together by memory. They pose questions: Where do I come from? Who are my people? Why does my blood run wild? These questions and so many more fly like dandelion fluff before me. Each one is a part of some greater whole but seems to have its own destiny. The seeds that find fertile ground yield occasional answers, which eventually send other questions into the breeze. But in the quilt that unfolds I hope I’ve captured what it took for a bird of a different feather to hatch, fledge, and take flight.

This is a memoir, then, but it is also the story of an ecosystem—of some land, the lives lived on it, and the dreams that unfolded there. It is a tale of an in-between place and its in-between people. And I tell it with a sense of responsibility. I believe the best way to begin reconnecting humanity’s heart, mind, and soul to nature is for us to share our individual stories. This is my contribution to that greater mission; sometimes the words that make the fragmented more whole need to come from someone in a different skin. Beyond that, however, I simply hope those words inspire you, too, to see yourself colored in nature’s hues.