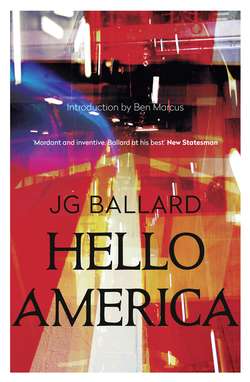

Читать книгу Hello America - J. G. Ballard, John Lanchester, Robert MacFarlane - Страница 6

Introduction

ОглавлениеBy Ben Marcus

Hello America might as well be called Goodbye America. Goodbye and so long, you monstrous, resource-sucking nation, who raped the land and air, imposed your hypocritical policies and cartoonish values every which where, and lowered the world’s collective intelligence through debased entertainment. Good riddance, and now let’s tour the corpse. This novel, more than any in his opus, is J. G. Ballard’s cruel eulogy to the country everyone loves to hate. America, we all know, has had it coming for a good while now. Since it first started to thrive, perhaps? In Hello America, that comeuppance has struck, and hard. The promised land has given way to wasteland, a blank slate. Welcome to the end times. Or is Ballard suggesting we need to wipe the great nation clean and start again, with a new group of well-meaning European explorers? Perhaps ‘hello’ is the correct word after all.

The novel opens to a dead America, the Statue of Liberty drowned in her own harbour. A group of explorers has come across the ocean to assess some worrying radiation levels. At first glance, our explorers find a New York that is covered in what looks like mounds of gold. Gold dust is spilling from buildings, running into the water. They’re rich! This is the American promise, writ not just large but gigantic, and their excitement is nearly childish. Of course this is Ballard, who would not reward his characters so soon, if ever. Their fates will not be resolved so easily. Up close, the explorers discover that this is not gold at all, but sand. America’s profligate way with all of the world’s resources has left it uninhabitable. Published in 1981, when America was still recovering from the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, Hello America is even more relevant, or terrifyingly accurate, today. Our sense of its premise’s inevitability quickly transforms the novel from sci-fi horrorscape to just another piece of domestic realism, plus some very appealing clone technology and ultra-sexy transparent flying machines late in the novel. The climate in this not-so-fictional world has been pitched on its head after the damming of the Bering Strait, and the explorers discover that not only did every American have to flee, they did so in a hurry. The metropolis is a desert. We can only guess at the wrenching weather that must have burned people out of their homes. The country is a graveyard of itself. This is perhaps just the cautionary tale we need as we lurch further into real, irreversible destruction, and since the hard-headed among us are not listening to science, why not let fiction commence its subtler, more sinister campaign?

Whatever kind of future Ballard is proposing here, it’s not one gifted with much remote intelligence, because each of our protagonists is filled not with hard facts about this failed part of the world, but with full-blown, unchecked fantasies of the America that awaits. Their scientific mission is quickly subsumed by more personal, mythological yearnings. In a place without people, a person can become whatever he wants. Even president. Although what one would be president of is never made especially clear. Leadership itself, in its pure form, as distilled prestige, is what one is meant to readily covet. For Ballard, instilling a character with a lifelong dream of becoming president is giving that character one of the greatest ambitions there is.

We know almost nothing about where our explorers have come from, only that Europe practised moderation with its resources and avoided America’s greedy, suicidal eco-disaster. If Europe survived, though, it would seem to be a pinched and thin survival, hardly worth the novel’s attention. It’s interesting to note that the explorers never think of home while in America, never wish they were elsewhere, and seem in fact to have no pasts to speak of at all. Their lives have begun anew in this strange place. Is this the powerful hold of the American dream, which has apparently outlasted the American reality? However fallen the new world is, however much it is a victim of its own excess, a new round of explorers would seem to prefer it, death-ridden as it is, to anything else on the planet. One begins to sense that underneath the clear and lurid scorn Ballard shows for what America had become, there simmers a circumspect romanticism, a longing for the place, however diseased it was. But for Ballard, romance and death are hardly ever separate. He has no trouble showing the allure of death. In his world, it’s better to throw one’s lot in with the crazy dreamers, however perilous the mission, than to conduct oneself more rationally, with modest and realistic hopes.

Still, Ballard does love to topple an icon, and here his destruction is as luscious, and perverse, as ever. A hollowed-out, depopulated America is a perfect playground for him. He needn’t trifle so much with characters when he can provide a running inventory of all that is gone, and one of the novel’s strongest currents is the endless account of those parts of America that no longer exist or no longer work. The book is a near-rhapsody of decline. Cities are sucked of life. Dust covers everything. Pools are empty, the lights are out, and the glass in buildings is warped or gone. Rarely has a writer seemed to take such glee in cataloguing what is missing in his narrative world, a kind of grave-dancing unparalleled in any other book I can think of.

The book bursts with American death, revels in it, in lieu, really, of any kind of old-fashioned character development. Ballard was long besotted with America, or, more specifically, with its cultural artefacts and over-hyped promise, the way it advertised itself through its exports. When the movie version of Crash was set to be filmed, Ballard applauded David Cronenberg’s decision to shoot the film in Toronto, bringing it closer to the land where cars were an ugly, compelling obsession. But if Crash was, in part, about death by car, Hello America is about the death of the car, and with it the American dream.

There is no page in this book that doesn’t vividly show how finished America is. If we often think that a novelist creates a world, it is more fitting to say that here Ballard, as he did so spectacularly in his disaster fiction, has destroyed one instead. The book makes rubberneckers of us readers, because who wouldn’t be fascinated by the destruction of a land and culture that, in our time anyway, feels so fatally dominant, so in need of humbling? For an American reader, it is about as close as one can get to attending one’s own funeral. We read with a full arsenal of emotions: fascination, fear, guilt, and glee. And as our explorers move west, we encounter Ballard’s real achievement: he has written a historical novel about the future. Hello America depicts a second discovery of America, this time by demented lunatics with destructive, conquering delusions of a place that would be empty and pointless but for their dreams of it. An abandoned America turns out to be the perfect landscape for his passionate, violent characters. If America is the great land of make-believe, then Ballard’s characters are the perfect torch-bearers for the life of the imagination. Even while the country itself has perished, Ballard shows us how it endures in fantasy, mattering perhaps more than the reality ever could.

New York, 2014