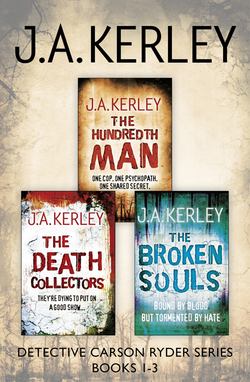

Читать книгу Detective Carson Ryder Thriller Series Books 1–3: The Hundredth Man, The Death Collectors, The Broken Souls - J. Kerley A. - Страница 30

Chapter 20

Оглавление“I started drinking when my brother died. Two years ago. Heavily, that is. I’d always liked it, from the first time I had a beer when I was sixteen. It made me feel, I don’t know, smart. I got the grades and did all the right things, but always felt dumb. Like I was faking it.”

Ava and I walked slowly along the beach. It was midnight deserted, just us and the waves and the slightest thread of breeze. Our footsteps crunched in the dry sand. I said, “Your brother, you mentioned him once. Lonnie?”

“Lane. He was four years older than me. I called him Smoke. It was my pet name for him because he moved so softly and quietly. I’d be sitting on the porch reading and he’d drift up and point at a cloud and begin describing the shapes in it…”

She’d started talking when I walked through the door, a flood of disparate thoughts connected only in that she wanted them out. I also felt she wanted to talk about her drinking, to pick it apart and study it. She wanted to understand how to ground herself when shadow lightning hissed and sizzled in her head, how to channel the current harmlessly into the earth.

“We could spend an entire afternoon studying the clouds. Or I’d watch him draw…”

We started toward my house, crossing the roll of the small dunes.

“As early as I can remember he was an artist; not a kid who did art. He’d amaze people with his insights and skill. I have six of his paintings at home.”

I recalled the brilliantly crafted abstracts on her walls, controlled explosions of color, joyous. “I saw them. No, that’s wrong: I was pulled into them.”

“The one by the couch? Red and gold and green? It’s called Crows. Most people see dirty black birds, Lane saw beyond, into their beauty. That’s how I felt when he was with me, he saw places where I was beautiful that were hidden to me. He used to call me or even come visit when I was in school. He kept me going, focused. I felt so alive when he was here.”

“How did he die?”

She stopped. Behind her, far down the strand, I saw whirling stars. Kids out burning sparklers, the Fourth wasn’t too far away.

“He committed suicide,” she said. “It turned out he had been seeing a psychiatrist for years. Depression. It tore our family to pieces.”

I watched the sparkling stars, said nothing.

“I thought back through all the times he’d seemed so happy, so alive. But he had this—this mental cancer in him, a thing with tentacles that kept growing until it tore him away from me, from our family, from everything.

“That was when I first fell apart. My anger turned to drinking and I took leave from school and stayed drunk for a semester. Sick, rotten drunk. The school knew about Smoke, about Lane. They thought I was just taking time off to deal with it.”

I wrapped her shoulders with my arm. “You were, Ava. Just not correctly.”

“When I started working here…there was no Smoke to call at night, no one to tell me I’d be fine. I’d have a bad day with Dr. Peltier and I’d go home and have a drink and suddenly it was morning and I was on the couch with an empty bottle in the kitchen. I’d fight it until the weekend and fall apart again. Then I’d be so ashamed I’d—”

She hung her head. “Damn, Carson, I have an MD and I can’t even begin to explain alcohol addiction. For an alcoholic to drink is a supremely irrational act. And yet, as scientifically and logically trained as I am, I drink. It’s insane.”

We stood quietly and watched the sparklers etch silver against the dark until they shrank into black. We headed back to the house. I heard music, Louis Armstrong blowing “Stars Fell on Alabama” through the sea oats. Harry was in my drive, sitting in his old red Volvo wagon and sipping from a bottle of beer. He heard us crunching through the sand and turned off the music.

“Sorry if I’m interrupting, Cars, but I wanted to run a couple things by you.”

I did the perfunctories as we climbed the steps. “Harry, Ava Davanelle, Ava, Harry Nautilus.”

“We met at a couple of posts,” Harry said to Ava.

“I probably wasn’t the best of company. I apologize.”

“I didn’t notice, Doctor; I tend to keep my distance when the chitlins are showing.”

We went inside. Ava picked up her AA book and said she was going to read. Harry sat on the couch and leaned forward, clasping his hands on a bouncing knee. “She doing any better, Cars?” he asked when the door closed behind Ava.

“Worn and shaky, but talking it out some tonight. Bear said that’s a good sign. What brings you to the water’s edge, bro?”

Harry scowled at the iced tea I’d set in front of him. “You got anything stronger, Cars?”

“In my trunk.”

“Sure could use a tot of scotch.”

I went to my car under the house and fetched the Glenlivet. Holding the gurgling bottle made me recall scrabbling through Ava’s car and finding the vodka. I stood below the bedroom and heard Ava’s footsteps creaking across the floor above.

My box in the air above an island.

The tide was receding, the waves a gentle hiss a hundred yards distant. I listened to Ava padding across the wood and hoped my small retreat might be where she found comfort. That it might do for her what it had done for me.

While in my first year of college, tired of the questions—“Are you any relation to…”—and the lies I answered with, I’d changed my name from Ridgecliff to Ryder. I took the name from Albert Pinkham Ryder, the nineteenth-century painter whose most enduring works are of men in small boats on dark and boiling seas. Changing my name was one of many changes back then, all designed to destroy the undestroyable fact that I was the son of a fiercely sadistic man and the brother of one who had murdered five women.

I’d quit college, joined the navy, returned to college, changing majors like changing shoes, finally planting deepest in psychology. Girlfriends came and went like meals. I changed hair, vehicles, speech patterns, magazine subscriptions. I once had five addresses in a year, not counting my car. I changed my name.

But every morning I still woke up me.

My mother died. I intended to use the inheritance money to buy a single-wide trailer and let the rest spin a tight but viable existence. When you sleep upward of a dozen hours a day, basic existence is not a hard nut to make. One day, fishing the surf, I saw this place. It stood in the air, but its underpinnings were sturdy. The windows were wide. The deck overlooked boundless water. It had a For Sale sign.

I couldn’t push the place from my mind and even dreamed of it, sometimes as a house, sometimes as a helmet with visor. I bought it two weeks later, knowing I’d have to work to keep it. Spurred by Harry’s remark about me making a good cop, I joined the police force and found the work honorable and necessary. It also let me see clearly, for the first time, what had been in front of me for years.

In the first few months on the street I learned vast helpings of the misery I encountered came from the participants’ inability to tear free of their pasts. Old slights simmered into grudges, grudges into gun-shots. Crackheads shambled inexorably from last bust to next vial. I watched hookers link and relink with the pimps who would eventually kill them, directly or indirectly. Don’t do it, I’d plead into faces confused by paths they felt driven to walk. Stop. Think. It doesn’t have to be like this. The past is nothing but a series of recollections; it doesn ‘t own you. Change before it’s too late.

Talking to myself.

One aspect of a tectonic shift in self-awareness—a revelation if you will—is it is ineffable, beyond description. So I can only say that on a normal afternoon one thousand and fifty-two days ago, I went to a locked footlocker in the farthest reaches of my closet and withdrew a black-handled knife I’d seen plunged into a squealing, desperate shoat. A knife Jeremy had hidden in the basement of our home. I tucked the knife beneath my shirt and took the ferry across the wide mouth of Mobile Bay. Midpoint in the journey, without ceremony or even a second glance, I sent the knife to join the broken craft of older wars.

The ferry brought me home, which is here, not there, now, not then. I figure if we are prisoners of the past, we are jailer as well.

I turned to go back upstairs and again heard Ava’s footsteps creak across the floor. She stopped directly above and for a moment we aligned from sand to stars. A need arose in my fingertips which I resisted as a quaint and silly notion, yet reached to touch the joists above my head. They’re wood, rough hewn and salt crusted, but to my fingers they seemed a kind of holy relic, one mingling human frailty with ceaseless faith…the bones of light, perhaps. I heard the door open and Harry called my name into the night, wondering where I was.