Читать книгу No Excuses - J. Larry Simpson I - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

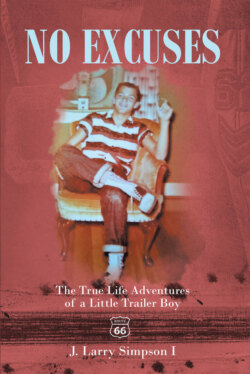

ОглавлениеStory 3

The Summer of ’56

It was still cool outside as spring was blooming in Gallatin. In March 1956, Dad came home from his diesel mechanic job and said gently, “Vicky, we’re moving to Northern Indiana to help build a new highway”—taking a deep calming breath—“close to Lake Michigan.”

Mom, just like always, sighed and wiped off a tear because she really didn’t want to move from Gallatin but said, “When do I have to be ready?”

She pulled me and my three little family members close to her stomach and hips and just held on. “It’ll be all right, and we’ll be ready.”

Mom could always do it—get over it, and comfort us, even with tears.

Sure enough, we were ready, the dogs loaded, and lunch prepared as the sun still lay behind the black eastern sky. Mom drove the car, a 1954 black-and-white Buick with the other kids with her and Dad and I in the green ’53 Ford truck. We pulled the fifty-foot home on wheels out onto North Water and North US Highway 31, we were rolling once again.

The farmland of Indiana, flat as a flitter, was okay with us. We liked the Tennessee hills better, but it was all right.

Forty-eight hours later, having slept at a truck stop in our moving home, we drove into La Porte. There weren’t many trailer parks, but Dad found one, paid the first months’ rent, and we set up camp! Being on the west side of town on Highway 2, Jeanie and I entered the same school, a new school, and set about making friends.

The teacher I was assigned to couldn’t get my name right—he called me Joe.

“No,” I said. “My name is Larry.”

But like most adults, he couldn’t get it. To him, my first name had to be the name. I put up with it; besides, I knew we wouldn’t be there long anyway. Not long after that, he was calling me “Larry Joe.”

I had never skated before, but there was a really nice skating rink just a half mile from the trailer park. So being invited to go with some friends, especially one girl, I went, more than once. But somehow, I couldn’t get it. Skating was hard for me even though I was a pretty good athlete.

Music playing, boys and girls skating close, boys flying, and girls swirling, I fell!

Ben, a rather “rotund” eighth grader rolled over my right hand. I never skated again. I knew what I liked. I never skated again.

Dad didn’t like where we lived. I don’t know why. But one of the great things about trailer living is you can move anytime you please. So Dad moved us to Westville, eleven miles away, and there began the saga I’m going to reveal.

*****

Westville

The town was known for its mental hospital. Jokes were always coming from others about any of us who lived there. Some or all of it was well placed.

One of the great things about Westville was that our great friends, the Rice’s, moved there also. John and Wilma only had one son whom they named Happy.

“Happy?” I said when we first met in Granada, Mississippi, where Dad and Mr. Rice worked together. Happy and I became close friends.

So when I heard the Rice’s were comin’, I jumped up and hit the ground runnin’.

We were buddies and could play together for hours.

The summer of ’56 started hot, and we had to make some friends. So we built a little “house” out of canvas, paper, lumber, logs, nails, wire, rocks, loose bricks, which we dug up out of the ground and plastic at the bottom of the railroad tracks. The railroad tracks were built upon a fifteen-foot-high bank, so it was exciting to have our “summer home” at the bottom with a few little trees and the train roaring above us flying.

After a few days in that hot June, Happy and I were talking about money. We needed some money. After all, we couldn’t buy any airplanes or trains to put together without money!

I loved airplanes. Eventually, I had about fifteen I had put together, and Mom and Dad let me hang them from the ceiling in mine and David’s bedroom. What a wonder. I could lay in bed early in the morning and fly anywhere and fight the Germans and Japanese! I always won those air battles. My mind flew in those planes.

So lying in the “railroad shack” one early morning, we talked about how we could make some money.

Mr. Rice recently had taken an old refrigerator down to the salvage yard, where they bought metal stuffs. So he suggested that we gather up any metal we could find, take it to the salvage store, and earn some money.

As divine providence has always been so good to me, we scouted the countryside and discovered that the west side of the land owned by the trailer park had been a railroad equipment storage facility, and guess what? Scattered over a half acre was metal of all kinds—some on top of the ground, and some covered up.

Getting the okay from the owner of the park, Happy and I started to work. Pulling all sorts of metal off the ground and out of the ground, we began our financial future. Rusty metal, a fender or two, metal strips, train car parts, engine parts, metal of all kinds lay like a buried treasure. With some cuts and bruises, we kept going.

From morning to night, we worked. Happy was a redhead and fair-complexioned while I was brown like a Navajo Indian. So the sun burnt him up, and I just got darker.

We were the talk of the trailer park. Ole Mrs. Jones fixed us lemonade. Mr. Jones loaned us a shovel. Mom and Wilma fixed plenty for lunch, and the other kids just made fun of us. But work we did.

By mid-July, we had a pile about six feet tall and thirty feet around.

Daddy said, “Son, it’s time to load all this up and take it to the salvage company.”

Dad drove his truck over to the “metal for sale” work pile, and we loaded it on the truck—six feet up and the bed filled full.

Arriving at the salvage yard, we were greeted by a very skinny tall man with a beard like Abe Lincoln and a black patch over his right eye. His hands were like saucers and all cracked up.

As Happy and I jumped out of the truck, he said, “Well, men, what have you got for us?”

I said, “You see all this metal? We brought it to you to sell,” never being one to mince words.

Ole Abe said with a growly voice, “Where did you get all this?”

So we told him the story while Dad stood back with a grin on his face from ear to ear.

Ole Abe said, “Pull your truck over here by the scales, and we’ll weigh it.” Having weighted it, he said, “You’ve got 649 pounds.”

Ole Abe was proud of we boys for doing all that work in six weeks as he pounded us on our backs. Dad was proud, still grinning his big smile. Our pay? It was to be .03 per pound!

Happy, speaking up like a man, said, “well, what’s it worth?”

Calculating every ounce, ole Abe said, “You’ve got $19.47 coming to you. Here, I’ll count it out.”

Count he did, and happy we were. What a pay day for twelve- and fourteen-year-old boys! We split it up, and Happy gave me the extra penny!

Going home, rejoicing all the way, we cleaned up and went downtown one long block and one short one away. First to the Black Hawk Grill for a chocolate milkshake and then across the street to the Variety Store where they had models of all kinds. Happy bought a Cadillac car, but I bought a B-17 Bomber to put together and hang it on the ceiling. It flew in my bedroom for five years until we traded out home on wheels for the new home on Grace Street in ’61.

Happy and I learned a lot that summer but especially that smart, hard work pays off.

Soon we would leave Westville and move back to Gallatin, but with the memory of the hot, moneymaking summer of ’56 forever on our minds.

How I wish I knew where Happy is so we could talk about it—the summer of ’56.

Even trailer boys have no excuses.

*****

The Black Hawk Grill

I wanted information for memories’ sake on the hot place for kids in Westville, the Black Hawk Grill.

In March 2018, I called the city building in Westville to see if anyone remembered the old meeting place.

A young lady answered the phone. I told her that I was looking for information on the grill. She didn’t seem very interested in helping me.

However, when I told her my story with the Black Hawk and this book, she instantly warmed up.

The nice young lady asked, an older lady in the office if she knew anything or someone to help. The younger ladies knew nothing of the famous spot. The gentle older lady said she knew someone who could help.

“Call Cheryl. She’ll remember!”

Wow.

Very excited, I called Cheryl’s number, got the answering machine, and told her what my interest was. Before the evening was over, Cheryl sent me an e-mail with a nice and knowledgeable response.

Being very excited, as I was also, she described the Black Hawk as the meeting place almost all the townspeople, but especially the young people.

But to top that, Cheryl said, “I worked in the grill from 1954 and into the summer of ’56!”

Amazing! She worked there for two to three months that I went there with Jeanie and Happy weekly. I’m quite sure I knew this lovely lady, saw her, or was waited on by her. Or did I? I can have no doubt, but that in the mystery of the streams of life I surely met Cheryl in the summer of ’56, or did I?

Sandy and I drove to Westville in early spring of 2018 to meet with Cheryl. She didn’t make the proposed rendezvous, and I couldn’t reach her by phone. I can only hope that life is good for a once upon a time Black Hawk Grill girl.