Читать книгу Killing Godiva's Horse - J. M. Mitchell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеScattered clouds gathered over parched earth. For two years, they gathered but brought no rain or snow. Nothing. Not here. The headwaters of the river saw plenty of snow, but clouds passed by the high desert and plateaus of northern New Mexico, waiting to reach Colorado before releasing their moisture. The dusty range held little for deer, pronghorn, cattle, horses, or any surviving animal. Those that remained stripped the land of leaf and stem. If they could jump the fences in search of food, they had done so long before now. If their search brought them here, they had put themselves on the wrong piece of range.

Year one brought concern. Year two, panic. Most ranchers gathered their stock and took them to pasture elsewhere, or sold them to wait out the drought. The animals remaining picked at desert scrub, searching for anything that could provide a little energy.

Cumulus clouds floated over the plateau, somehow appearing a little more numerous, a little taller, a little bluer along the edges, but the cloud cover was not complete. Just wandering clouds, as had been the case for two years.

One cloud settled over the plateau, seemingly held there, possibly by thermals rising up to meet it. Other clouds slowed to wait, only teasing the earth with virga—their rain drops evaporating before reaching the ground—but this cloud, as if defying an established plan, let go and poured. The San Juan Mountains, visible only moments before in the distance, now lay hidden behind a veil of rain draping from the cloud.

The ground, splattered by raindrops, sucked up what it could. With few plants to help with the task, soil was soon overcome. Trickles formed and streamed downslope. Those trickles joined others, then sheets, then water marching toward drainages, coming together to form creeks, and those came together in a rush to the river.

With parched ground for miles in all directions—except here, under one cloud—no one downstream expected what was coming. A wall of water.

—·—

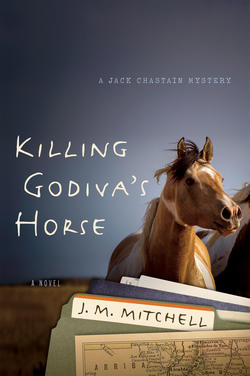

“Here we go,” Jack Chastain said to himself.

He let the kayak drift, pulled by the current toward the tongue feeding into the rapid. With long arms, he dipped one end of his paddle, held it, and turned the kayak across channel. He studied the boiling water below.

Seems different than a minute ago.

What do you expect? Scout a rapid from the hillside, it always seems different. Have some faith.

He pointed the bow forward and let the kayak slip into the tongue. Slow, calm waters turned quick. Waves crashed over the kayak’s deck. Only one option now . . . to see it through.

Current pushed the kayak toward boulders, nearly submerged, a swirling hole in between. He paddled left, through foam and splash. The river fought back, not letting go, pulling him right. He paddled harder. The hole grew large. Water slipping over boulders, calm, then turbulent.

Keep away from that hole.

He glided onto the rim—water plunging. He paddled hard, fast. Again. Again. Again.

The kayak pulled away, into the current flowing past.

Now, only the small stuff.

He sucked in a breath, and let the paddle skim the surface, holding the kayak on line. He cut through the last of the waves and settled onto flat water, soaking wet, water shedding off his life vest and Park Service uniform. Paddling into the eddy at river left, he slipped around, then raised the paddle with both arms.

Paul Yazzi, waiting above the rapid, returned the signal. Slipping into the current, he let his kayak float forward. He entered the tongue, picking up speed. Waves crashed over him, obscuring all but his helmet. The ends of his paddle appeared in alternating flashes, in and out of the water. He pressed for river left. Gliding toward the boulders, he worked one end of the paddle, stalled on the lip, and slowly pulled away. Free but balance lost, he slipped over, waves crashing over him. The bottom of the orange kayak bobbed in and out of whitewater, then up-righted. Yazzie dashed through the last of the rapid. Hitting flat water, he steered into the eddy.

Jack let out a holler. “And we call this work.”

Yazzi smiled and pulled off his helmet. He ran fingers through wet, black hair, then over his face, shedding the water streaming between wide-set cheeks.

“C’mon Paul, even men of few words gotta cut loose on a day like today.”

“I am avoiding paying for a helicopter,” he said, his words heavy with Navajo accent. “We finish reading veg plots. You go back to your project.”

“Can you believe it? Middle of a drought, all this from the headwaters.”

“Confuses things. Range beat to hell, much water in the river.” Yazzi let his paddle balance on the deck of his kayak. “I appreciate your help. I am sorry to pull you away from the report to agencies and Congress.”

Jack turned away.

“You want me to keep you from your work?”

Jack let the thought settle over him. “It’s done. Mostly.”

“Good. What’s next?”

“The Congress part.”

“Good.”

“Not sure it is. I’m starting to think we should limit our actions. Do what we can without dealing with politicians.”

“Why?”

“Because . . . of their games.”

“We need new authorities. To do the things to keep ranchers and environmentalists working together. And why would Congress care? Unless they’re from New Mexico?”

Jack furrowed his brow, and let out a long, seething breath.

“You’re angry. This is not like you.”

“Sorry, Paul.” He pulled off his helmet, loosened the strap on his sunglasses, and slipped them off. He gave his head a shake. Wet, brown strands settled over blue eyes. He swept them away from his face. “It’s just . . . .” He scowled. “Never mind.”

“Famous white man saying—all politics are local. Let our members of Congress earn their keep.” Paul skimmed the water with his paddle. “You’ve done much good here, Jack. Three years ago, the president created the national monument. Afterwards, hell. Everyone fought. Now, they work together. They remember they’re part of the same community. You made that happen. Don’t stop now.”

“It was your work, too, Paul.” Jack sighed. “As much as I want us to do what we can to help preserve this little part of the world, keep people together, help them save what they value . . . the next phase scares me.”

Yazzi laughed. “You white guys. You think too hard. Do this. You’re good at it.”

Jack shrugged, and slipped on his helmet. “Where to now?”

“Next drainage, on the right. We’ll climb out to monitoring sites. Important ones.”

Jack paddled into the current, then waited for Paul to come alongside.

The gorge grew wide, its walls pulling back from the river. Around a bend, on river right, two rafts came into view, beached on the sand. Paddling close to shore, they approached the rafts. Half a dozen men sat under a cottonwood, alongside a creek feeding into the river. River guides—one male, one female—hunkered over a table, picking at food and packing it away.

Chastain and Yazzi came ashore, upstream of the rafts.

The male guide, in river shorts and white Grateful Dead T-shirt, looked up. “Rangers!” he hollered, “hide the contraband.”

“Contraband?” a client hollered back, sounding confused.

The guide laughed, and tossed back his long, sun bleached hair.

“Hey, Stew.” Jack crawled out of the kayak, stood, and stretched his tall, lanky frame. He took hold of the webbing on the bow of the kayak, and dragged it onto the sand. “Who’s your partner? New guide?”

Stew, lean and muscled, let out a yawn. “Sorry, I need a nap. This is Lizzy. Lizzy McClaren. Not exactly new. She started last summer.”

“Haven’t had a chance to meet,” Jack said, extending a hand.

The woman looked up through locks of curly red hair, her green eyes piercing. Equally lean, shoulders muscled, she wore a sleeveless sun dress, threadbare and sun bleached. She set down the knife, shook the hand, and finished chewing. “You are?”

“Jack Chastain, Park Service. This is Paul Yazzi, Bureau of Land Management.” He gave her dress another look. Typical river guide. Squeaking by. Doing whatever it takes for a life on the river.

She glanced at Yazzi and took another bite. “We still in the park?”

“You left the park a few miles back. You’re in the national monument, one of the reaches managed by BLM.”

“I figured as much.” She backed away. “No time to chat. If we wanna good camp, we gotta keep moving.” She lugged a stack of plastic containers to the downstream raft, reached over the tube, opened an ice chest, and tossed them in. She turned back. “Unless you’re doing inspections, we’ll see you down river.” She waved her clients over. “Load up,” she shouted.

“Inspections? No.” Jack glanced at Stew, then back. “This is a science trip.”

“I see,” she said, unfazed. She held a garbage bag open to the clients as they climbed into the raft. Following them over the tube, she stashed the bag, and pointed to life vests. “Get yours on first, then someone hand me mine.” She plopped down and took hold of the oars. Stew untied her line, setting her adrift.

As Stew’s clients boarded, he turned to Jack. “She’s good,” he whispered. “Sometimes a little distant. She’s from back east. New York.”

“No worries. Catch you over beer at Elena’s.”

“Deal, we’ll . . . ” Stew paused. He cupped an ear.

Jack heard it. Low. Rumbling. Growing by the moment. Rising over the sound of the river.

Paul turned to listen. “That cannot be.”

The sound. Rock against rock, water pounding walls.

Willow and cottonwood leaves rustled. Breeze turned to gust.

“Smell that?” Jack said, turning to Yazzie.

He nodded.

“What?” Stew asked.

“Dirt.” He glanced at the sky. Blue, scattered clouds. But, . . . “Get your people upslope. Now.” He pointed upstream. “There. Do it fast.”

Stew rushed his boat. “Get out. Quick!” Clients jumped from the tube and ran, feet fighting sand.

Jack waved the other boat to shore, an eye on the side canyon. The sound grew loud, a freight train barreling toward them, hidden by serpentine cuts through the rock.

Lizzy pushed the oars. The raft lurched forward, bumping the shore. Two men jumped, already running. Lizzy started after, but stopped. A third man tugged at a river bag lashed to the boat frame. She clutched the man’s arm and pulled, jerking him back. His glasses flew off. He fought as she pulled.

Ready to move, Jack glanced from boat to side canyon. The rumble changed. Air shook. He watched as water exploded from the canyon. Dark, filthy water, laden with debris, tens of feet high. “Run.”

“Leave ’em!” Lizzy shouted.

The man ripped his arm away and reached for his glasses. He put them on. His eyes grew wide.

Paul dashed toward talus, dragging his kayak. Jack waited seconds, then followed, grabbing his in a tenuous hold as he moved away from the surge.

It hit. Water, debris, the surge scooping up the rafts, flipping them over, pushing them into the current, belly up. The rafts floated downstream, through a bend of the river.

Jack lost sight of them. Two people. Gone. Possibly dead. He exchanged glances with Paul, then Stew, then the others.

Questioning looks. None with answers.

He tugged on his splash skirt, and caught a look of concern from Paul. “I know. Bad idea,” Jack said. “What else can we do?”

“Do not do this,” Paul said.

“Surely, there’s not another wall of water coming.”

“You do not know that.”

“Right.” Jack studied the dark tongue. Dirty water slithered downriver, carrying limbs, whole trees, and debris. He moved upstream and pulled the kayak to water’s edge. Paddle in one hand, he slipped in and pulled the splash skirt over the rib of the cockpit. “The next mile’s flat water, right?”

“Normally,” Paul shouted, over the roar. “In a flood? I do not know. Do not get yourself killed!”

Jack gave a nod. “See if you can get someone on the radio.” He plunged one end of the paddle.

Crossing the river, he skirted past the inflow, avoiding debris, pushing limbs away with the paddle, working toward open water.

At the bend, one raft sat eddied out, river-right, going nowhere. No people. None he could see. He floated past, into a straight stretch, water fast and turbulent. Ahead floated the second raft, upside down, one person—a head and an orange vest—bobbing in and out of sight in the midst of debris. No way to tell if they’re okay. The second person? Nowhere to be seen.

Plowing forward, he closed the gap. The second person? Where?

There. Alongside the raft.

Arms flailed, slipping, attempting to climb on. No hand holds.

Who first? Which?

A log floated at the raft. He cut left, toward it.

Red hair. The Lizzy woman. He overtook the log and pushed off with the paddle, propelling the kayak alongside the raft. “Take hold of the grab loop. I’ll pull you to shore.”

“No. Gotta save Maynard,” she screamed. “Gotta save the boat.”

She took the grab loop and hefted herself onto the bow, pitching Jack forward. He lay back, countering the weight. “You’ll never . . .”

She wriggled her way onto the tube, giving a kick, pitching the kayak back.

He rolled. Warm, dirty water. Debris. He thrust the paddle, rolling himself upright.

“Where’s Maynard?” Lizzy hollered. She paced, corner to corner on the belly of the raft, water dripping from her, feet slipping. “Where? Under the boat?”

“Downstream,” Jack shouted.

A swell hit the raft, throwing Lizzy on her face, washing over her and sending her willowy body sliding along the rubber. She managed to stay on.

Jack steadied the kayak, and glanced up river. Another swell.

He caught a look on Lizzy’s face. Fear.

He followed her eyes.

A boulder, mid-river, split the stream, collecting debris. A cottonwood bole bobbed in the water, trapped against it, it’s leaf-covered limbs pushing back the current. Water boiled.

Maynard, his head nested in orange, floated toward it.

“Swim, Maynard!” Lizzy screamed. “To shore. Swim.” She stepped forward, onto the tube.

“Don’t!” Jack shouted. “Let me get . . . ”

She dove.

Surfacing, she plunged her arms in and out of the water, swimming toward the orange vest.

A swell hit the raft, floating it over her. She disappeared.

Pushed by the swell, Jack paddled toward the man, closing the distance. “Maynard, look at me!” Jack shouted. “Look at me!”

The man’s head turned.

Jack reached under the splash skirt, found his throw bag, and hurled it toward him. Line fed out. The bag splashed down behind the man, rope splatting on the surface. “Grab hold!”

The man flailed, fumbling for line, managing a grasp. Jack clipped the end to his vest and made a quick right, paddling toward shore. “Kick!” he ordered, feeling the drag of the man.

A swell hit the kayak, broadside, capsizing him. A thrust on the paddle and Jack kept it rolling, losing his sunglasses but uprighting the kayak, keeping it pointed to shore. The man, still kicking, came aground. Grasping willow branches, he pulled himself out of the water.

Jack spun around, catching sight of Lizzy upstream of the raft. It slammed into the cottonwood pinned to the boulder.

The next swell hit, pushing the raft into the crown of the tree. Limbs held the bow, as the force of the water stood the raft on end, flipping it onto the shattered mass. Lizzy, bobbing in the water, rose with the swell, hefting herself onto the log. A wave carried her up the bole, dragging her over splintered branches. Her movement stopped. She reached down, tugged, then stood, leg bleeding, dress in shreds. She stumbled up the log, working her way toward the raft. As she approached, the raft broke free, spinning in the current, scraping past the boulder. Stunned, she watched it float away. A wave washed over her. She scooted toward the boulder, holding onto branches as the next surge hit.

Jack pulled in the line, stuffing the throw bag. Upstream or down? Current’s too fast. Has to be up.

He paddled upstream along the bank, then kicked into the current. Floating toward her, he took hold of the bag. “Be ready to swim!” he shouted. He tossed it. Line fed out.

She caught it one-handed.

The log shifted. He tried a hard turn. A limb cut him off. A swell picked up the kayak, floating it over the log, dropping it against the boulder. The bole shifted, pinning the kayak. Jack ripped off the splash skirt and squirmed out of the cockpit, crawling onto rock. The kayak shattered.

He scrambled up the boulder.

Lizzy stood watching, blood dripping from a gash on one thigh, her dress in tatters, a spaghetti strap gone, long rips exposing her thighs and side. She gathered the tears in one hand, and held out the rope with the other. “So, now,” she muttered, “what am I to do with this?”