Читать книгу From Superman to Man - J.A. Rogers - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

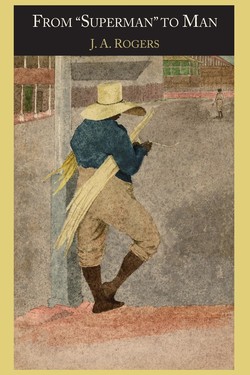

FROM “SUPERMAN” TO MAN FIRST DAY

Оглавление“A moral, sensible and well-bred man

Will not affront me; and no other can.”

—Cowper.

THE limited was speeding to California over the snow-blanketed prairies of Iowa. On car “Bulwer” the passengers had all retired, and Dixon, the porter, his duties finished, sought the more comfortable warmth of the smoker, where he intended to resume the reading of the book he had brought with him, Finot’s “Race Prejudice.” He had been reading last of the Germans and their doctrine of the racial inferiority of the remainder of the white race. Having found the passage again, he began to read:—“The notion of superior and inferior peoples spread like wildfire through Germany. German literature, philosophy, and politics were profoundly influenced by it——”, when a passenger rushed into the room.

“Is this Boone we are coming into, porter?” he demanded excitedly and in a foreign accent, at the same time peering anxiously out of the window at the twinkling lights of the town toward which the train was rushing.

“No, sir,” reassured Dixon, “we’ll not be in Boone for twenty minutes yet. This is Ames.”

“Thank you,” said the passenger, relieved, “the porter on my car has gone to bed, and I feared I would be carried beyond my destination.” He then started to leave but when half-way, turned and asked, “May I ride here with you and get off when we get there?”

“Certainly, sir,” welcomed Dixon, cordially, “make yourself at home. Where are your grips?” and dropping his book on the seat, Dixon went for the grip.

When Dixon returned the passenger was reading the book.

“Thank you,” he said, as Dixon placed the grip in a corner. Then holding out the book he said, “I took the liberty to look at your book, and I find it’s an old favorite of mine.”

“Ah, is it?” exclaimed Dixon with heightened cordiality.

“This is the first English translation I have seen,” continued the passenger, “and I think it pretty good.”

“Yes, sir, very good. But I prefer it in the original.”

“In the original!” exclaimed the passenger. “Vous parlez français, alors?”

“Mais oui, Monsieur.”

“Where did you learn French,—in New Orleans?” continued the passenger, in French.

“I began it in college and learnt it in France,” responded the porter, in the same language.

“You have been in France! What part?”

“Bordeaux.”

“Bordeaux? How long were you there?”

“Two years and a half.”

“Studying?”

“No, sir. I was Spanish correspondent for Simon and Co., wine merchants.”

“You speak Spanish, too, eh? What are you, Cuban?”

“No, American, but I have been to Cuba. I learned Spanish in the Philippines.”

“You have travelled a great deal, I see.”

“Yes. It seems to be just my luck. I returned from the Philippines in time to get a position as valet to a gentleman about to tour South America, becoming six months later his private secretary. Together we also visited the principal countries of the world. Mr. Simpson died while we were in Bordeaux. That accounts for my stay there.”

“Didn’t you like it in France?”

“Oh, I like it better than anywhere else on earth, but Simon & Co. failed on account of the bad crops and I was thrown out of work. As I had been longing to see the folks at home I returned to America.”

“I should think with your knowledge of French and Spanish you ought to be able to get a better job than this.”

“Well, I have never been able to get one, and when one has a family he must get the wherewithal to live some way.”

“But have you tried to get something better?”

“I am trying continually. On my return from Europe I advertised for a position as French and Spanish correspondent. I received a good many replies, but when my prospective employers saw me, they all made various excuses. There was one, though, who, declaring he was broadminded, would have employed me, but his offer was so small that I refused it on principle.”

“Too bad for a man of your stamp and education. You said you went to college? Do you mind coming a little closer. I can’t hear for the noise.”

“I spent a semester and a half at Yale, then the war broke out and I enlisted,” said the porter, drawing nearer.

They then went on to speak about railroad life, the passenger telling Dixon about an incident that had occurred that afternoon between the porter on his car and a fussy passenger, and concluded by asking Dixon if he met many such persons.

“No,” was the reply. “Nearly all the persons I meet on the road are very pleasant. I am sure that if that wise old Greek who said, “Most men are bad!” had gained his knowledge of human nature on a sleeping car his verdict would have been altogether different. I never knew before that there were so many kind, agreeable persons until I had this position. One meets a grouchy person at such rare intervals that he can afford to be liberal then. I can recall an incident similar to the one you have just told me. Would you care to hear it?”

“Certainly.”

“One day while waiting on a drawing-room passenger I made a mistake. This man, who had got on the train with a grouch, having previously wrangled with the train- and the sleeping-car conductors, at once began to abuse me vociferously in spite of my earnest apology. I took it all calmly, at the same time racking my mind for some polite, but effective retort. As I noted the ludicrousness of his ruffled features an inspiration came to me, whereby I could bring his conduct effectively to his notice. In the room was a full-length mirror, made into the state-room door. Swinging this door around I brought it right in front of him, where he could get a full view of his distorted features, at the same time saying with good nature, ‘see, sir, the mirror does you a strange injustice, today.’ The ridicule was too much for him. He stopped immediately, then started to explode again, and, apparently at a loss for words, sat down. He later proved to be one of the finest passengers I have ever served.”

The two then began to exchange experiences of French life, reverting soon after to the subject of the book and its author.

“I remember the great stir created by this book when it appeared in 1905,” said the passenger. “Finot has done a great service for humanity. He well merits the honor conferred on him—Officer of the Legion of Honor.”

“He is called one of the makers of modern France,” added Dixon. “Did you know that despite his French name, he is a Pole?”

Then, espying the twinkling lights of the town, he exclaimed. “Ah, here we are coming into Boone now.”

“Good-by,” said the passenger, with genuine regret in his voice, “I’m sorry that our acquaintance is so short. I’m stopping here only for the night and I will go on to Los Angeles tomorrow. I’d like to have had you all the way.”

“I’m sure you’ll have a pleasant porter tomorrow,” said Dixon cheerily, as he grasped the proffered hand. They bade each other good-by, and Dixon turned hastily to assist the new-coming passengers. After Dixon had assisted the new arrivals to bed he returned to the smoker and resumed his reading, but too tired to concentrate his thoughts on the scientific matter, he closed the volume, placed it behind him in the hollow formed by his back and the angle of the seat and began to reflect on the last passage he had read:—

“The doctrine of inequality is emphatically a science of white peoples. It is they who have invented it.”

The Germans of 1854, he reflected, built up a theory of the inferiority of the other peoples of the white race. Some of these so-called inferior whites have, in turn, built up a similar theory about the darker peoples. This recalled to him some of the many falsities current about his own people. He thought of how in nearly all the large libraries of the United States, which he had been permitted to enter, he had found books advancing all sorts of theories to prove that they were inferior. Some of these theories even denied them human origin. He went on to reflect on the discussions he had heard on the cars and other places from time to time, and of what he called “the heirloom ideas” that many persons had concerning the different varieties of the human race. These discussions, he went on to reflect, had done him good. They had been the means of his acquiring a fund of knowledge on the subject of race, as they had caused him to look up those opinions he had thought incorrect in the works of the standard scientists. Moved by these thoughts he took a morocco-bound notebook from his vest pocket and wrote:—“This doctrine of racial superiority apparently incited the other white peoples, most of whom were enemies to one another, to unite against the Germans, and destroy their empire. Will the doctrine of white superiority over the darker races produce a similar result to white empire?”

But at this juncture his thoughts were interrupted by the entrance of someone. Looking up he saw a man clad in pajamas and overcoat, and with slippered feet, enter the room.

Now Dixon had taken special notice of this man for, during the afternoon, he had been discussing the color question with another passenger in the smoker. From what Dixon had overheard, the man just entering was a Southern senator on his way to California on business.

Dixon had had occasion to go into the room several times. On one occasion he had heard this man say vehemently “The ‘nigger’ is a menace to our civilization and should be kept down. I am opposed to educating him, for the educated ‘nigger’ is a misfit in the white man’s civilization. He is a caricature and no good can result from his ‘butting in’ on our affairs. Would to God that none of the breed had ever set foot on the shores of our country. That’s the proper place for a ‘nigger’,” he had said quite aloud, on seeing Dixon engaged in wiping out the wash bowls.

At another time he had heard the same speaker deliver himself of this opinion:—“You may say what you please, but I would never eat with a ‘nigger.’ I couldn’t stomach it. God has placed an insuperable barrier between black and white that will ever prevent them from living on the same social plane, at least so far as the Anglo-Saxon is concerned. I have no hatred for the black man—in fact, I could have none, but he must stay in his place.”

“That’s nothing else but racial antipathy,” his opponent had objected.

“You don’t have to take my word for it,” said the other, snappily. “Didn’t Abraham Lincoln say: ‘there is a physical difference between the white and black races which, I believe, will forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality?’ Call it what you will, but there is an indefinable something within me that tells me that I am infinitely better than the best ‘nigger’ that ever lived. The feeling is instinctive and I am not going to violate nature.”

Upon hearing this remark, Dixon had thought as follows: “My good man, how easily I could define that ‘indefinable feeling’ of which you speak. I notice from your positive manner, and impatience of contradiction that you experience that indefinable feeling of superiority not only towards Negroes, but toward your white associates as well and that feeling you, yourself, would call in any one else ‘conceit.’ ”

Dixon had happened to be present at the close of the discussion, which had been brought to an end by the announcement of dinner. The conversation had been a rather heated one and had closed with this retort by the anti-Negro passenger.

“You, too, had slavery in the North, but it didn’t pay and you gave it up. Wasn’t your pedantic and self-righteous Massachusetts the first to legalize slavery? You, Northerners, forced slavery on us, and when you couldn’t make any more money on it, because England had stopped the slave trade, you made war on us to make us give it up. A matter of climate, that’s all. Climes reversed, it would have been the South that wanted abolition. It was a matter of business with you, not sentiment. You Northerners, who had an interest in slavery, were bitterly opposed to abolition. It is all very well for you to talk, but if you Yankees had the same percentage of ‘niggers’ that we have, you would sing a different tune. The bitterest people against the ‘nigger’ are you Northerners who have come South. You, too, have race riots, lynching and segregation. The only difference between South and North is, that one is frank and the other hypocritical,” and he added with vehement sincerity, “I hate hypocrisy.”

In spite of this avowed enmity toward his people, Dixon had felt no animosity toward the man. Here, he had thought, was a conscience, honest but uneducated.

Shortly afterward an occupant of the smoker who had been puffing a huge calabash with Indian stolidity met Dixon in the passage way. Prefacing his remarks with a few terrible, but good-natured oaths, he said, “That fellow is obsessed by the race problem. I met him yesterday at the hotel, and he has talked of hardly anything else since. This morning we were in the elevator, when a well-dressed Negro, who looked like a professional man, came in, and at once he began to tell me so that all could hear him something about ‘nigger’ doctors in Oklahoma. If he could only see how ridiculous he is making himself he’d shut up.”

“I feel myself as good as he,” he went on to say, “and I have associated with colored people. We have a colored porter in our office—Joe—and we think the world of him. He doesn’t like ‘niggers,’ eh?” Then with a knowing wink, nudging Dixon in the ribs at the same time, he added with another oath, “I wager his instinctive dislike, as he calls it, doesn’t include both sexes of your race. I know his kind well.”

Dixon had felt like saying, “We must be patient with the self-deluded,” but he did not. He had simply thanked the speaker for his kind sentiments, then turned and walked away.

All of this ran through the porter’s mind when he saw the pajama-clad passenger appear in the doorway. The newcomer, on entering, walked up to the mirror, where he looked at himself quizzically for a moment, then selected a chair and adjusting it to suit his fancy made himself comfortable in it; next, he took a plain and well-worn gold cigarette case from his pocket, selected a cigarette, and, after tapping it on the chair, began rummaging his pockets for a match, all in apparent oblivion to the presence of Dixon at the near end of the long cushioned seat. But Dixon had been quietly observing him and deftly presented a lighted match, at the same time venturing to inquire in a respectful and rather solicitous tone, “Can’t sleep, sir?”

“No, George,” came the reply in an amiable, but condescending tone, “I was awakened at the last stop and can’t go back to sleep. I never do very well the first night, anyway.”

With this the senator began to talk to Dixon quite freely, telling him of his trip from Oklahoma. They soon began to talk about more personal matters. Into this part of the conversation the senator injected phrases such as ‘darkies,’ ‘niggers’ and ‘coons.’

From this he began to tell jokes about chicken-stealing, razor-fights and watermelon feasts. Of such jokes he evidently had an abundant stock. Nearly all of these Dixon had heard time and again. One was the anecdote of a Negro head-waiter in a Northern hotel who, when asked by a Southern guest if he were the head ‘nigger,’ indignantly objected to the epithet, but upon the visitor’s informing him that it was his custom to give a large tip to the ‘head-nigger’ this head-waiter, so the story goes, effusively retracted, saying, “Yessah, Boss, I’se de’ head niggah,’ and pointing to the waiters, added, “and ef you doan b’leave me ast all dem othah niggahs deh.”

The narrator was laughing immoderately, and so was the listener. Had the entertainer been a mind reader, however, he might not have been flattered by his success as a comedian, since it was his conduct, and not his wit, that was furnishing the porter’s mirth.

While the senator was still laughing the train began to slow down, and Dixon, asking to be excused, slid to the other end of the seat to look out, thus exposing the book he had placed behind him. The senator saw the volume and his look of laughter was instantly changed to one of curiosity.

The book stood end up on the seat and he could discern from its size and binding that it was a volume that might contain serious thought. He had somehow felt that this Negro was above the ordinary and the sight of the book now confirmed the feeling.

A certain forced quality in the timbre of Dixon’s laughter, as also the merry twinkle in his eye, had made him feel at times just a bit uncomfortable, and now he wanted to verify the suspicion. His curiosity getting the better of him, he reached over to take the volume, but at the same instant Dixon’s slipping back to his former seat caused him to hesitate. Yet he determined to find out. He demanded flippantly, pointing to the book,—“Reading the Bible, George?”

“No, sir.”

“What then?”

“Oh, only a scientific work,” said the other, carelessly, not wishing to broach the subject of racial differences that the title of the book suggested.

Dixon’s very evident desire to evade a direct answer seemed to sharpen the other’s curiosity. He suggested off-handedly, but with ill-concealed eagerness: “Pretty deep stuff, eh?” Then in the same manner he inquired, “Who’s the author?”

Dixon saw the persistent curiosity in the other’s eye. Knowing too well the nature of the man before him, he did not want to give him the book, but being unable to find any pretext for further withholding it, he took it from the seat, turned it right side up, and handed it to the senator. The latter took it with feigned indifference. Moistening his forefinger, he began turning over the leaves, then settled down to read the marked passages. Now and then he would mutter: “Nonsense! Ridiculous!” Suddenly, in a burst of impatience he turned to the frontispiece, and exclaimed in open disgust: “Just as I thought. Written by a Frenchman.” Then, before he could recollect to whom he was talking—so full was he of what he regarded as the absurdity of Finot’s view—he demanded—“Do you believe all this rot about the equality of the races?”

Now Dixon’s policy was to avoid any topic that would be likely to produce a difference of opinion with a passenger, provided that the avoidance did not entail any sacrifice of his self-respect. In this instance he regarded his questioner as one to be humored, rather than vexed, for just then the following remark, made by this legislator that afternoon, recurred to him:

“The Jew, the Frenchman, the Dago and the Spaniards are all ‘niggers’ to a greater or lesser extent. The only white people are the Anglo-Saxon, Teutons and Scandinavians.” This, Dixon surmised, had accounted for the remark the other had made about the author’s adopted nationality, and it amused him.

As Dixon pondered the question there occurred to him a way by which he could retain his own opinion while in apparent accord with the passenger. He responded accordingly:—

“No, sir, I do not believe in the equality of the races. As you say, it is impossible.”

The senator looked up as if he had not been expecting a response, but seemingly pleased with Dixon’s acquiescence he continued as he turned the leaves: “Writers of this type don’t know what they are talking about. They write from mere theory. If they had to live among ‘niggers,’ they would sing an entirely different tune.”

Dixon felt that he ought not to let this remark go unchallenged. He protested courteously: “Yet, sir, M. Finot had proved his argument admirably. I am sure if you were to read his book you would agree with him, too.”

“Didn’t you just say you didn’t agree with this book?” questioned the senator sharply, looking up.

“I fear you misunderstood me, sir.”

“Didn’t you say you did not believe in the equality of the races?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then why?”

“Because as you said, sir, it is impossible.”

“Why? Why?”

“Because there is but one race—the human race.”

The senator did not respond. Despite his anger at the manner in which Dixon had received and responded to his question, he stopped to ponder the situation in which his unwitting question had placed him. As he had confessed, he did not like educated Negroes, and had no intention of engaging in a controversy with one. His respect and his aversion for this porter had increased with a bound. Now he was weighing the respective merits of the two possible courses—silence and response. If he remained silent, this Negro might think he had silenced him, while to respond would be to engage in an argument, thus treating the Negro as an equal. After weighing the matter for some time he decided that of the two courses, silence was the less compatible with his racial dignity, and with much condescension, his stiff voice and haughty manner a marked contrast to his jollity of a few minutes past, he demanded:

“You say there is only one race. What do you call yourself?”

“An American citizen,” responded the other, composedly.

“Perhaps you have never heard of the word ‘nigger’?”

“Couldn’t help it, sir,” came the reply in the same quiet voice.

“Then, do you believe the ‘nigger’ is the equal of the Anglo-Saxon race?” he demanded with ill-concealed anger.

“I have read many books on anthropology, sir, but I have not seen mention of either a ‘nigger’ race or an Anglo-Saxon one.”

“Very well, do you believe your race—the black race—is equal to the Caucasian?”

Dixon stopped to weigh the wisdom of his answering. What good would it do to talk with a man seemingly so rooted in his prejudices? Then a simile came to him. On a visit to the Bureau of Standards at Washington, D. C., he had seen the effect of the pressure of a single finger upon a supported bar of steel three inches thick. The slight strain had caused the steel to yield one-twenty-thousandth part of an inch, as the delicate apparatus, the interferometer, had registered. Since every action, he went on to reason, produces an effect, and truth, with the impulse of the Cosmos behind it, is irresistible, surely if he advanced his views in a kindly spirit, he must modify the error in this man. But still he hesitated. Suddenly he recalled that here was a legislator: was one of those, who, above all others, ought to know the truth. This thought decided his course. He would answer to the point, resolving at the same time to restrict any conversation that might ensue to the topic of the human race as a whole and to steer clear of the color question in the United States. He responded with soft courtesy:

“I have found, sir, that any division of humanity according to physique, can have but a merely nominal value, as differences in physiques are caused by climatic conditions and are subject to a rechange by them. As you know, both Science and the Bible are agreed that all so-called races came from a single source. Scientists who have made a study of this question tell us that the Negro and the Yankee are both approaching the Red Indian type. Pigmented humanity becomes lighter in the temperate zone, while unpigmented humanity becomes brown in the tropics. One summer’s exposure at a bathing beach is enough to make a life-saver darker than many Indians. The true skin of all human beings is of the same color: all men are white under the first layer.

“Then it is possible by the blending of human varieties to produce innumerable other varieties, each one capable of reproducing and continuing itself.

“Again, anthropologists have never been able to classify human varieties. Huxley, as you know, named 2, Blumenbach 5, Burke 63, while others, desiring greater accuracy, have named hundreds. Since these classifications are so vague and changeable, it is evident, is it not, sir, that any division of humanity, whether by color of skin, hair or facial contour, to be other than purely nominal, must be one of mentality? And to classify humanity by intellect, would be, as you know, an impossible task. Nature, so far as we know, made only the individual. This idea has been ably expressed by Lamarck, who, in speaking of the human race, says,—“Classifications are artificial, for nature had created neither classes, nor orders, nor families, nor kinds, nor permanent species, but only individuals.”

The senator handed back the book to Dixon, huffily. “But, you have not answered my question yet,” he insisted, “I asked, do you believe the black race will ever attain the intellectual standard of the Caucasian?”

“Intellect, whether of civilized or uncivilized humanity, as you know, sir, is elastic in quality. That is, primitive man when transplanted to civilization not only becomes civilized, but sometimes excels some of those whose ancestors have had centuries of culture, and the child of civilized man when isolated among primitives becomes one himself. We would find that the differences between a people who had acquired say three or four generations of beneficent culture, and another who had been long civilized would be about the same as that between the individuals in the long civilized group. That is, the usual human differences would exist. To be accurate we would have to appraise each individual separately. Any comparison between the groups would be inexact.”

“But,” reiterated the other, sarcastically, “you have not answered my question. Do you believe the black man will ever attain the high intellectual standard of the Caucasian? Yes or no.”

“For the most authoritative answer,” responded Dixon in the calm manner of the disciplined thinker, “we must look to modern science. If you don’t mind, sir, I will give you some quotations from scientists of acknowledged authority, all of your own race.”

Dixon drew out his notebook.

“Bah,” said the other savagely, “opinions! Mere opinions! I asked you what you think and you are telling me what someone else says. What I want to know is, what do YOU think.”

“Each of us,” replied Dixon, evenly, “however learned, however independent, is compelled to seek the opinion of someone else on some particular subject at some time. There is the doctor and the other professionals, for instance. Now in seeking advice one usually places the most reliance on those one considers experts, is it not? This afternoon I overheard you quoting from one of Lincoln’s debates with Douglas in order to prove your views.”

Silence.

Dixon opened his notebook. After finding the desired passage he said:

“In 1911 most of the leading sociologists and anthropologists of the world met in a Universal Races Congress in London. The opinion of that congress was that all the so-called races of men are essentially equal. Gustav Spiller, its organizer and secretary, voiced the findings of that entire body of experts when, after a careful weighing of the question of superiority and inferiority, he said (here Dixon read from the notebook):

“ ‘We are then under the necessity of concluding that an impartial investigator would be inclined to look upon the various important peoples of the world as, to all intents and purposes, essentially equal in intellect, enterprise, morality and physique’ ”

Dixon found another passage and said: “Finot, whose findings ought to be regarded as more valuable than the expressions of those who base their arguments on sentiment or on Hebrew mythology, says,—‘All peoples may attain this distant frontier which the brains of the whites have reached.’ He also says:

“ ‘The conclusion, therefore, forces itself upon us, that there are no inferior and superior races, but only races and peoples living outside or within the influence of culture.

“ ‘The appearance of civilization and its evolution among certain white peoples and within a certain geographical latitude is only the effect of circumstances.’

“Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, in his paper before the Universal Races Congress, says:

“ ‘Give the Africans without any mingling of rancor or oppression a high and humane civilization, and you will find their mental level will not differ from ours. Abolish the whole of our civilization and our minds will sink to the level of an African cannibal. It is not a difference of mentality in the race, but a difference of instruction.’ ”

Dixon closed his note-book and said, “The so-called savage varieties of mankind are the equal of the civilized varieties in this:—there is latent within them the same possibilities of development. Then the more developed peoples have the germ of decay more or less actively at work within them.”

The senator had been awaiting his turn with impatience. Now drawing up his overcoat over his pajama-clad knees, and raising his voice in indignation, apparently forgetting all previous qualms of lowered racial pride, he flung at Dixon: “That’s all nonsense. It is not true of the Negro, for while the white, red and yellow races have, or have had, civilizations of their own, the black has had none. All he has ever accomplished has been when driven by the whites. Indigenous to a continent of the greatest natural resources, he has all these ages produced absolutely nothing. Geographical position has had absolutely nothing to do with it, or we would not have had Aztec civilization. Tell me, has the Negro race ever produced a Julius Caesar, a Shakespeare, a Montezuma, a Buddha, a Confucius? The Negro and all the Negroid races are inherently inferior. It is idiocy to say the Negro is the equal of the Caucasian. God Almighty made black to serve white. He placed an everlasting curse on all the sons of Ham and the black man shall forever serve the white.” And his face flushed with excitement.

Dixon was apparently unmoved. He responded with charming courtesy, his well-modulated voice and even tones in sharp contrast to the bluster and hysteria of the other. “The belief that the history of the Negro began with his slavery in the New World, while popular, is highly erroneous. The black man, like the Aztec, was civilized when the dominant branches of the Caucasian variety were savages. You will remember, sir, that Herodotus, the Father of History, an eyewitness, distinctly mentions the black skins, and wooly hair of the Egyptians of his day. In Book II, Chapter 104, of his history he says,

“ ‘I believe the Colchians are a colony of Egyptians, because like them they have black skins and wooly hair.’

“Aristotle in his ‘Physiognomy,’ Chapter VI, distinctly mentions the Ethiopians as having wooly hair and the Egyptians as being black-skinned. Count M. C. deVolney, author of ‘the Ruins of Empire,’ says:

“ ‘The ancient Egyptians were real Negroes of the same species as the other present natives of Africa.’

“A glance at the Sphinx or at any of the ancient Egyptian statues in the British Museum will confirm these statements. When I saw the statue of Amenemphet III, I was immediately struck by the facial resemblance to Jack Johnson. I have seen Negroes here and in Africa, who bore a striking resemblance to King Sahura of the V Dynasty. By the light of modern research it does appear as if white-skinned humanity got its civilization from the black-skinned variety, and even its origin. Volney says:

“ ‘To the race of Negroes … the object of our extreme contempt … we owe our arts, sciences and even the very use of speech!’

“And with reference to the production of great men by the Negro …”

The senator, who had been fidgeting in his chair, now interrupted testily:—“But what about the Negro’s low, debased position in the scale of civilization? Look at the millions of Negroes in Africa little better than gorillas! They are still selling their own flesh and blood, eating human flesh and carrying on their horrible voodoo! All of the white race is civilized and all the other races, to some extent. Consider the traditions of the white man and all it means! Look at the vast incomprehensible achievements of the white man,—the railroads, the busy cities, the magnificent edifices, the wireless telegraphy, the radio, the ships of the air,—yes, consider all the marvels of science! What has the white man not done? He has weighed the atom and the star with perfect accuracy. He has probed the uttermost recesses of infinity and fathomed the darkest mysteries of the ocean; he has challenged the lightning for speed and equalled it; he has competed with the eagle in the air, and outstripped him; he has rivalled the fish in his native element. In fact, there is not one single opposing force in Nature that he has not bent to his adamant will. He has excelled even the excellence of Nature. Consider, too, the philosophies, the religions, the ennobling works of art and of literature. Has the Negro anything to compare? Has he anything at all to boast of? Nothing! And yet in the face of all of these overwhelming facts, things patent to even the most ignorant, you tell me the Negro is the equal of the breed of supermen—wondermen—I represent? Really this childlike credulity of yours reaches the acme of absurdity. More than ever do I perceive a Negro is incapable of reasoning.”

And he caught for breath as he lolled back in the chair, while a supreme smile of satisfaction lit his features.

Dixon, who had been listening patiently, was seemingly unaffected. He responded composedly:—“The white man’s civilization is only a continuation of that which was passed on to him by the Negro, who has simply retrogressed. ‘Civilizations,’ as Spiller has pointed out, ‘are meteoric, bursting out of obscurity only to plunge back again.’ Macedonia, for example! In our own day we have seen the decline of Aztec and Inca civilizations. Of the early history of man we know nothing definite. Prior even to paleolithic man there might have been civilizations excelling our own. In the heart of Africa, explorers may yet unearth marks of some extinct Negro civilization in a manner similar to the case of Assyria forgotten for two thousand years, and finally discovered by accident under forty feet of earth. For instance, the Chicago Evening Post of Oct. 11, 1916, speaking editorially of the recent discoveries made at Nepata by Dr. Reisner of Harvard, says—“To his amazement he found even greater treasures of the Ethiopian past. Fragment after fragment was unearthed until at last he had reconstructed effigies of no less than eleven monarchs of the forgotten Negro empire.” Since then the tombs of fourteen other kings and fifty-five queens have been unearthed by the Reisner expedition. Among them is that of King Tirkaqua, mentioned in the book of Isaiah. An account of this appeared in the New York Times, November 27, 1921. Again, great Negro civilizations like that of Timbuctoo flourished even in the Middle Ages. Then there have been such purely Negro civilizations as that of Uganda and Songhay, which were of high rank. Boas says in his ‘Mind of Primitive Man’ (here Dixon took out his notebook): ‘A survey of African tribes exhibits to our view cultural achievements of no mean order. All the different kinds of activities that we consider desirable in the citizens of our country may be found in aboriginal Africa.’ ”

The senator did not reply. He had narrowed his eyes, which like two slits, were peering at Dixon piercingly. The latter, returning his gaze, continued undauntedly:—“Spiller also says—‘The status of a race at any particular moment of time offers no index to its inherent capacities.’ How true has this been of Britons, Picts and Scots, and Huns. Nineteen hundred and seventy years ago England was inhabited by savages, who stained themselves with woad, offered human sacrifices and even practiced cannibalism. Nor is culture a guarantee against decay or Greece would not have decayed. You may be sure the Roman had the same contempt for the savages of the North, who finally conquered him and almost obliterated his civilization, as have the self-styled superior peoples of today for the less developed ones. But these undeveloped peoples should not be despised. Nature, it certainly appears, does not intend to have the whole world civilized at the same time. Even as a thrifty housewife retains a balance in the bank to meet emergencies, so Nature retains these undeveloped varieties as a reserve fund to pay the toll which civilization always exacts. Finot says that many biologists regard the Caucasian as having arrived at the limit of his evolution, and that he can go no higher without danger to his overdeveloped brain. Undeveloped peoples, like undeveloped resources, sir, are simply Nature’s bank account.”

The senator readjusted his slippers and went over to the water cooler for a drink. He did not like to argue in this vein. Dixon’s quiet assurance and well-bred air, too, surprised him, and made him unconsciously admit to himself that here was a Negro different from his concept of that race, and not much different from himself after all. Yet his racial pride would not permit him to be outwitted by one he regarded as an inferior in spite of that ‘inferior’s’ apparent intelligence. He would try the tactics best known to him,—the same that he had more than once used successfully with Negroes. He would outface his opponent, awe him, as it were, by his racial prestige. With this determination he returned to his seat and calmly seated himself. After a few leisurely puffs of a freshly-lighted cigarette he turned to Dixon, who had not moved, and in pretty much the same tone that a bullying lawyer would use to a timid witness, shaking an extended forefinger and glaring from under his knitted eyebrows, he demanded:—

“Do you mean to tell me that you really believe the Negro is the equal of the white man? That YOU think you are as good as a white man? Come on now, none of your theories.”

Dixon appeared far from being intimidated. Indeed, he was secretly amused. Carefully repressing his mirth, he asked with sprightly ingenuousness:—

“In what particular, sir?”

The senator, it appears, had not foreseen an analysis of his question, for he stammered:

“Oh, you know very well what I mean. I mean—well—well—do you feel you are the equal of a white man?”

“Your question has answered itself,” responded Dixon.

“In what way?”

“Well, sir, if I could tell how a white man feels, which I would have to do to make the comparison, then it would mean that I, a Negro, have the same feelings as a white man.”

No response. Silence, except for the rumbling of the train. After a short pause, Dixon continued,—“Since, as your question implies, I must use the good in me as a standard by which to measure the good in a white man, I believe that any white man, who like myself is endeavoring to do the right thing, is as good a man as I. And more, sir,” he added in a tone of gentle remonstrance, “your question has been most uncomplimentary to yourself, for, in asking me whether I consider myself as good as a white man, you are assuming that all white men, irrespective of reputation, are alike.”

The senator appeared more confused than ever. His face flushed and his eyes moved shiftily. But he was determined not to be beaten. Rallying to the charge, he began in an irritable and domineering tone: “You said you were born in Alabama?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Your father was a slave, wasn’t he?”

“My grandmother, sir,” corrected Dixon frankly.

“Well, what I want to get at is this:—do you, the descendant of a slave, consider yourself the social equal of a white man, who has always been free, and who owned your people as chattels?” And he finished austerely: “Come on now, no more beating around the bush.”

Dixon decided to accept his meaning. In a tone that implied a perfect mutual understanding, he began:—“Of course, sir, this is a matter that deeply concerns our country and humanity, and so I feel that we two can speak on it calmly and without any ill feeling.” Then in a polite and convincing tone, he explained,—“Reared, as I was, in a part of the South where a white skin is deified and a black one vilified, candidly, in my childhood, I did believe that there was something about the white man that made him superior to me. But, fortunately for me, I have travelled and read considerably. I once worked for one Mr. Simpson, a lecturer. While with him I visited the principal countries of the world. In one English town, where I lived six months, I didn’t see a dark face. Living thus exclusively among whites, I observed that, except for differences due entirely to environment, my people were essentially the same as the whites. Indeed, what struck me most in my travels was the universality of human nature. European-reared Negroes possessed, so far as I could discern, the same temperament and manner, class for class, as the whites. Then my position on these cars has given me a rare opportunity for continued observation. I have met white persons in all kinds of relationships, and if there is any inherent difference between Negro and Caucasian, I have failed to find it after sixteen years of rather careful observation. It is needless to say, sir, that my ideas of superiority based on lack of pigment or texture of hair evaporated long ago.

This reply seemed to nettle the senator still more. He demanded with increased irritation, “But what about slavery? The Negro has been a slave since the dawn of history. Consult any dictionary of synonyms, and you will see the term ‘Negro’ is synonymous with ‘slave.’ A black skin has ever been a livery of servitude. Isn’t this world-old slavery a sign of the Negro’s hopeless inferiority? My father had hundreds of slaves!”

Dixon noticed the senator’s increased agitation and determined to be calmer than ever. He replied with a blandness that exasperated the other still more:—“Strange as it may sound, sir, the Caucasian has never been really free. The vast majority of its members are today, industrially, the serfs, and mentally, the slaves of the few. But, if we accept the term literally, all or nearly all branches of the white variety of mankind have been slaves that could be bought and sold. Britons were slaves to the Romans. Cicero, writing to his friend, Atticus, said,—‘The stupidest and ugliest slaves come from Britain.’ Palgrave, an English historian, says of the Anglo-Saxon period,

“ ‘the Theowe (Anglo-Saxon slave) was entirely the property of his master, body as well as labor; like the Negro, he was part of the live stock, ranking in use and value with the beasts of the plough.’

“Villenage persisted in England until the sixteenth century. Certain classes of Anglo-Saxon slaves were not even permitted to buy their freedom, since it was contended that their all was the property of their masters. Serfdom was not abolished in Prussia until 1807, and in Austria until 1848. Even here in America white persons were slaves. There were Irish slaves in New England.”

“Irish slaves in New England?” echoed the other in scornful surprise.

“Yes, sir, Irish men and women were slaves in New England, being sold like black slaves and treated not a whit better. Many of the most socially prominent in America have slave ancestors. Lincoln’s ancestors were white slaves. According to Professor Cigrand, Grover Cleveland’s great-grandfather, Richard Falley, was an Irish slave in Connecticut. There were also white slaves in Virginia. Black and white slaves used to work together in the fields in Barbados. Indeed, it would be quite possible to find white persons living in this country who were born in actual slavery, such having come from Russia, where slavery was abolished the same year our Emancipation Proclamation was signed. I refer you to Wallace’s ‘Russia.’ At this very moment white women are on sale in the Turkish and Moroccan markets, where anyone, Negroes included, may buy them. Hence you see, sir, the white man has no special advantage over the black in the matter of slavery.”

Dixon paused a moment, then added: “But I should think that the stigma attached to slavery would be more justly placed on the descendants of slaveholders than on the offspring of slaves. Is it not the kidnapper, and not the kidnapped, who is the odious one? With all deference to your parentage, my opinion is that slaveholders were parasites of the most pernicious kind.”

The senator glared angrily at the porter. He was exasperated at the argument but saw no way of getting out of it. He arose hastily, stopped, paced the smoker, then resumed his seat. After a few moments he insisted:

“But the Negro, himself, acknowledges his racial inferiority. Just look how he bleaches his skin, straightens his hair, and uses other devices to appear like the white man! Isn’t that a sign of inferiority? Imitation is acknowledgment of superiority. Do you see any other race thus imitating the looks of the white man? I can’t imagine a more comical sight than a Negro dandy with his hair all ironed out until it looks like the quills upon the fretful porcupine. Imagine a white man darkening himself to look like a Negro!” Then he added, sneeringly, “The Negro is ashamed of himself. If he believes himself the equal of the white man, his actions certainly do not show it.”

Dixon started. He had never looked at this matter in this light before. Now he pondered his reply.

The passenger noted his silence with a smile of satisfaction. Dixon found his response.

“Yes, these Negroes, who ‘doctor’ themselves to appear white do acknowledge inferiority. I have always held that one’s hair or color of skin is as perfect as nature can make them, so perfect that to tamper with either is the surest way of spoiling them eventually.”

“So much the worse for the black man, then,” retorted the senator, sarcastically, “that he should try to ape a race below him. He is just inferior, that’s all. The best proof is that he acknowledges it himself. When a man acknowledges his faults, don’t you believe him?”

“Indeed, sir,” retorted Dixon. “It is clearly the fault of the average white that these so-called Negroes should try to be other than they are. In a country where a drop of ‘Negro’ blood, more or less visible, and a ‘kink,’ more or less pronounced, in the hair may altogether change the current of one’s life, what can you expect?”

Dixon paused an instant, then continued: “I will give you an instance: two brothers intimately known to me arrived in New York from abroad. The hair of one brother did not indicate Negro extraction, that of the other did. The straight-haired one obtained a position commensurate with his ability. Incidentally, he went South and married a white woman. The other, the better educated and more gentlemanly of the two, too manly for subterfuge, after fruitless endeavor, had to take a porter’s job. He finally went back home in disgust.”

Dixon added reflectively, “Also do not forget that if certain Negroes iron their curly hair to make it straight, certain whites also iron their straight hair to make it curly. Madame Walker, it is said, made a million dollars by straightening the hair of Negroes; Monsieur Marcelle made about twenty times that by the reverse process among the whites. The whites, also, by bleaching their complexion and hair, wearing false hair, and the like, make a false show too, don’t they? Whose superiority are they aping then?”

The senator shifted in his seat uncomfortably! After a few moments he responded a shade less confidently, but with greater bluster, “What about this, then:—the Negro shows no originality, not even so far as contemptuous epithets are concerned. The white man calls the Negro ‘nigger’ and yet the Negro accepts it even to the length of calling himself so. Fancy a white man calling himself by a name given to him by Negroes! The Negro is a mimic. He has the same amount of reasoning power as a poll-parrot.”

“Yes,” admitted Dixon, “a great number of uneducated Negroes, also a goodly number of those with more book-learning, do act in a manner to warrant your statement. The habit that far too many Negroes have of calling themselves by those objectionable epithets given them by their white contemners cannot be too strongly condemned, and yet, isn’t the surest way of nullifying a nickname to call yourself by it? Anyway, I have been to South America and the Negroes there would never think of addressing one another thus. Indeed, even a full-blooded Brazilian Negro feels hurt if called a Negro in pretty much the same way that a descendant of the Pilgrim Fathers would be if called an Englishman. The Brazilian wishes to be known solely by his national patronymic.”

“Because he is ashamed of his race,” retorted the passenger.

“Not necessarily,” replied Dixon. “In Brazil, where slavery existed as late as 1888, the Negro is taught not only to regard himself the equal of the white man, but he is given an opportunity to prove it. There is no walk of Brazilian life, official or unofficial, where he is not welcome and which he has not filled. I have been credibly informed, that more than one Brazilian president has been of Negro descent. In the United States, on the other hand, it does appear as if everything possible is done to humble the so-called Negro, to suppress his self-respect. There ought to be small wonder then, if many Negroes do not show sufficient manly dignity, and many others, without weighing the purport, try to appear white, an act, that, after all, somewhat parallels that of the white man who blisters himself in the sun in an endeavor to appear, no doubt, like the bronzed heroes of the story books.”

The passenger did not respond. He appeared to be busily engaged in studying the inlaid woodwork. Dixon then added with assumed gravity:—

“I must concede, however, sir, that the average Negro acknowledges his inferiority tacitly and often by speech.”

The senator straightened up instantly. He smiled triumphantly and replied with an air of finality, “Well, that settles the argument. I knew you would finally come to the truth.” And he rose as if to go.

“But, in this instance,” Dixon queried archly, “might not an acknowledgment of inferiority prove a certain superiority?”

“Inferiority proving superiority!” shouted the other, dropping back into his seat. “What are you saying, anyway?”

“Doesn’t the case of the sexes explain this seeming paradox? The average male human, as you will admit, is egotistic. The more that woman, the weaker, humors this trait, the better she serves her own interest; similarly, the average white man’s weak point is his color egotism, and the more the Negro humors this failing, the more he serves his own interest. The greater the self-interest of the woman, the more credulous she appears to tales of masculine prowess; the greater the self-interest of the Negro, the more he flatters the white man’s egotism. Now, sir, who is cleverer, the fooled or the one who fools?”

The other did not reply.

Dixon continued: “I’ll give you an illustration. A friend of mine, a doctor, told me he was one day in a bar-room in Chicago when a man whom he instantly recognized as a Southerner, by his dress and manner, entered. Lounging in a corner was a Negro, one of those human beings who elect to live by their wits. No sooner had the Southerner ordered his drink than the Negro walked up and looking at him admiringly, said gushingly, “What a pretty white man! Say, boss, yo’ is from Mizzourah, ain’t yo’?”

“Yes,” confirmed the other, much flattered at this open admiration, “an’ wheh ah yo’ fum?”

“Oh, boss, how kain yo’ ast me dat?” said the Negro in mock indignation, eagerly eyeing the white man’s glass. Then he wheedled, “Say, boss, I’ll have a ‘gin an’ rass,’ too,” (raspberry wine and gin, a favorite drink among certain classes in Missouri). The Negro had the drink, and the white man in paying pulled out a large roll of bills. The sight of so much money fired the Negro’s eloquence. He redoubled his flatteries, telling his host how the Northern ‘niggers’ were ‘biggity,’ how they thought themselves ‘as good as a white folks,’ and when he had his victim flattered to the seventh heaven of delight, he sprang a hard luck story. The result was several more ‘gin-an-rasses’ and a dollar!”

Dixon related the incident in a breezy manner, but the senator failed to see any humor in it.

“From what you say,” he objected coldly, “the white man must have been very ignorant. And then might not a ‘nig——’ Negro permit himself to be thus flattered by a white man?”

“Possibly. But this story, and similar ones I could tell you, prove that acknowledgment of inferiority often means self-interest. The case of Booker T. Washington, however, proves a better example. Washington got along well in the South because he knew just how to tickle the color-vanity of the whites. Had he shown the more assertive spirit of DuBois, he would not have done so well in the South. But, I am opposed to this policy of trying to gain by subterfuge or blandishment, that which is one’s divine right!”

Silence for a few moments. The passenger appeared to be thinking deeply. Then he asked, “But how are you going to account for this? A Negro thinks himself superior to other Negroes in proportion to his amount of Caucasian blood. Isn’t that an instinctive acknowledgment of inferiority?”

“It is true,” conceded Dixon, “that many lighter-skinned Negroes do look down on their darker brothers. Many others shun them, too, from economic necessity; that is, they can earn more by passing for white. But, in the first instance, can’t we find a similar thing among the whites? Mark you, I am not defending this inexcusable ignorance among so-called Negroes. I have always held that the man who protests against a thing should be the last man to practice it. In the United States a premium is set upon Caucasian blood (of course, I use the term figuratively), hence, some mixed bloods believe themselves of superior caste. In the United States, due to the absence of a nobility, a premium is set upon Mayflower descent, and many persons so descended pride themselves upon their superiority due to ancestry—blue-bloods—F. F. V.’s, yea, even from the dark-skinned Pocahontas. And the analogy we might draw from Europe and its nobility is too evident to need further comment. Then it must be remembered that there is considerable rivalry between the brunettes and the blondes. I have heard rather heated arguments between white women of these types as to their respective merits. Blondes, having the lesser amount of pigment, are supposed to be the more virtuous, which, perhaps accounts for the large number of chemical blondes among women of your race…. and mine, too.”

“But those among us who have an infusion of Caucasian blood have nothing to boast of since such are in the position of children who have been abandoned by one of their parents. Then, too, whenever such are discovered among the whites they are always unceremoniously thrust out. In my opinion the Negro who plumes himself upon his white descent simply does not think.”

The bell had begun to ring just as Dixon was finishing, and he went in to answer the call. He was very glad of the interruption and remained away, hoping thereby to break off the argument, but the senator, it appears, had no such intention, for when Dixon ten minutes later had occasion to re-enter the room he was immediately assailed with:

“There is another important point of Negro inferiority. The features of the Caucasian are more pleasing, not only to the Caucasian, but to the Negroes, judging from their own comments. No one would ever think of comparing the physiognomy of a Negro with that of an Adonis or an Aphrodite.

The white man’s native sense of beauty will never permit him to modify his ideals.” He paused, then added with conviction : “The Negro’s physiognomy will ever make him un-pleasing to the white man.”

Dixon thought of telling him that this matter of physiognomy was the cause of all the trouble, but replied, instead: “The features of the Caucasian are, as a rule, more pleasing only to his own eye for each human variety, except when imbued with the thoughts of another people, as the Negro in the New World, considers its facial casts the standard. Darwin, in his ‘Descent of Man,’ says that when the Negro boys on the east coast of Africa saw Burton, the explorer, they cried out:

“ ‘Look at the white man! Does he not look like a white ape?’

“Winwood Reade said that the Negroes on the Western Coast admired a very black skin more than one of a lighter tint. Agbebi, a West African scientist, says in his paper before the Races Congress (here Dixon consulted his notebook):

“ ‘The unsophisticated African entertains an aversion to white people, and when accidentally or unexpectedly meeting a white man, he turns or takes to his heels, it is because he feels that he has come upon some unusual or unearthly creature, some hobgoblin or ghost or sprite, and that an aquiline nose, scant lips, and cat-like eyes afflict him.’

“Dan Crawford, the famous African missionary, tells of an instance where a number of Negro women in Central Africa, on seeing a white man for the first time, nearly broke down a doorway in their frantic haste to escape. The Yoruba word for white man is not complimentary. It means ‘peeled man.’ Stanley, the explorer, said that when he returned from the wilds of Africa he found the complexions of Europeans ghastly ‘after so long gazing on rich black and richer bronze.’ ”

The brakeman, passing by, peered into the room, but only greeted Dixon and went on.

When he was gone Dixon continued: “Oriental ideas of beauty are also different from ours. The Japanese do not like the noses and eyes of the Caucasian, which happen to be the very parts of Japanese physiognomy the Caucasians like least. Now, as Von Luschan asks, ‘Which of these races is right, since both are highly artistic?’ ”

“But,” protested the senator, rather lamely, “since the white race is the super—most developed one, its standard of beauty ought to be accepted as the universal one.”

Dixon noted with satisfaction the other’s hesitation at the word ‘superior.’ He responded:

“Environment is largely responsible for facial contour. Peoples subjected to the beneficial influences of Science and Art have, according to the standard of civilized man, more refined features and are consequently more beautiful than so-called savages.

“But facial beauty is only one side of the story. Venus and Apollo, as you will remember, are as famous for their beauty of bodily outline as for their facial contour, perhaps more so. And in a matter of bodily beauty certain primitive tribes easily excel the white man. The Zulus, a black people, are the successors of the ancient Greeks in beauty of physique. J. H. Balmer, explorer and lecturer, says:

“ ‘The Zulus are the physical superior of other races. A male Zulu has the strength, endurance and body of a prizefighter in the pink of condition. Their shoulders are broad, their chests deep, their waists slim. Their women are the strongest females propagated.’

“But here in America,” resumed Dixon, “it is not a matter of facial contour or physique. It is a question of color and texture of hair, sometimes color alone, sometimes hair alone, since there are many Negroes who possess the regular profile of the conventional Caucasian whilst there are many Caucasians who, but for color and hair might be representatives of any other human variety, except the true Mongolian. I have remarked many Swedish and Irish persons with Negroid features. Then, too, the beauty of colored women commands consideration. In all those parts of the British Empire where black and white live, those women who have what is known as a ‘touch of the tar-brush’ easily excel the average white woman in beauty and grace of expression. The white women of these countries are mostly English, and the Englishwoman, generally speaking, is not considered beautiful. And even here in America, where the blending of the various peoples and the superior economic conditions have combined to produce types perhaps of world-excelling beauty, certain types of colored women are the peers of any. The bewitching languor of form and voice, the placid depth of the soft, sparkling eye, and flawless texture of skin, combine with a disposition of artless amiability to make a charm that must move the hearts of all who venture to behold her. I must not forget to add that a large number of white people do think Negroes more beautiful than members of their own group. But I consider this question of facial beauty a wearisome one. The ultimate question has always been that of the mental and moral worth of the individual. Measured by the Greek standard of facial contour, Socrates, Herbert Spencer, Darwin, Voltaire and Steinmetz were ugly, and yet, the services they rendered to humanity are almost inestimable. Whilst ideas of beauty are purely individual, the standard of nobility of soul is universal. Character, then, should be the standard by which to judge human beings. After all, man is not like cattle which we rear for appearance’ sake. I think that any face lit up by right living and high ideals is beautiful regardless of contour.”

The senator seemed agitated. He got up and again paced the room. After a few turns he sat down and drew deep inhalations from his cigarette, blowing out the smoke very slowly. He was marshalling in his mind all the many points regarding Negro inferiority.

Suddenly, as if struck by an inspiration, he said triumphantly: “I can positively prove the Negro is inherently inferior. The Jews were slaves to the Egyptians who, according to you, were Negroes, for four hundred and thirty years, one hundred and eighty years longer than were the Negroes in America. Did they emerge in the debased condition of the Negro? No! Why? You also said that the Irish were slaves in New England, didn’t you? Well; today these former slaves dominate the United States politically. Here’s where the inferiority comes in. There are twelve millions of Negroes in the United States—a greater number than the population of Canada, greater than the combined population of Holland and Switzerland—and yet there is not a single Negro in any position of political importance in this country. A few, it is true, hold federal positions, mostly unimportant, however. If the Negro were not the inferior, would he allow himself to be thus outclassed?”

“I will first answer your question about the Jews. When they emerged from slavery they had, according to the Bible, their Jehovah to perform wondrous miracles for them, feeding them free, capturing cities, etc., hadn’t they? The Negro started with nothing and has had to fight his own battle every inch of the way.

“Again the Negro’s inferior position isn’t due to inferiority of human variety, but to inferiority in numbers.”

“To inter-racial jealousy, you mean; the surest sign of a consciousness of inferiority among any people. Race prejudice only hurts those who have a consciousness of their racial inferiority. The Negro can’t trust himself. He hates to associate with his own people.”