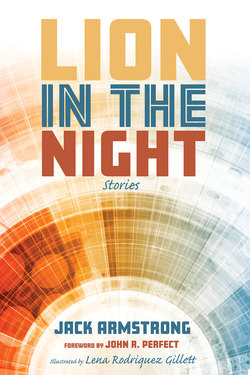

Читать книгу Lion in the Night - Jack Armstrong - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I THOUGHT YOU WERE ALONE

ОглавлениеA quiet, intense man, Dad sat in front of me at the breakfast table on assignment from my mother.

“So you want to be a doctor?” he started.

“I think I’ll enroll in pre-med in the fall,” I countered.

“We don’t have any doctors in the family, and you don’t know anything about doctoring or what a hospital is like.” A matter-of-fact engineer, Dad liked to start conversations with a statement of facts.

“I guess I’ll learn in time, Dad,” I replied.

“What kind of work are you doing this summer?” he asked emphatically. Dad held a dim view of summer vacations. As he worked hard, he figured his son should, too. Once I had suggested summer hockey camp and within one week I had a demanding job painting Pontiac Grand Ams on the night shift assembly line.

“Not sure yet, Dad.”

“There’s a job as an orderly at Beaumont Hospital in Birmingham available next week. Here’s the number to call.” He got up to leave, paternal duty fulfilled.

Soon I was employed as a night orderly at Beaumont Hospital in Birmingham, Michigan, a prosperous, midwestern town. The hospital was easy to reach, just a thirty-minute drive down wide, four lane Woodward Avenue, flanked by suburbs. I drove to work each night in my Mom’s white Corvair (unsafe at any speed) with a four-speed manual transmission and infamous rear engine.

At night in the hospital I learned that the women prevailed. Most of the male doctors were either home, in the Emergency Department, or working late in the operating room. Sometimes I was assigned to Surgical Prep where a friendly group of six middle-aged women meticulously prepared the surgical packs for the next day’s surgery. They liked teaching me about the packs, but laughed when I untied their aprons or sang Elvis songs while we worked.

Occasionally I was called to the medical wards to assist the beleaguered nurses, often with agitated, older men. One night I was called up STAT (like right now!) to find a small, young nurse attempting to calm a large, older man who was pacing the hall, his gown open in the back to reveal his generous bare bottom. As he strode back and forth he would periodically shout, “Help!” or ”What’s that?” The nurse explained to me that the man was going through DTs, or delirium tremors, from alcohol withdrawal and needed to return to his room where she could safely sedate him. I approached the old guy, known only as Mr. Brad, and asked him what the problem was.

“You don’t see them? Don’t tell me you don’t see them?” he asked.

“Yeah, Mr. Brad, I think I do. But what do you see?”

“Bugs, son. Bugs on the walls, some on the floors, more flying around me.” He swatted the air and stamped his feet at the same time. His hands trembled and his face twitched, but he wasn’t really angry, just upset.

“You know, between us, I bet we could catch most of these bugs, then scoop them up and throw them out the window in your room,” I said.

“You think? And you’d help me?” He now looked directly at me, both twitching eyebrows arched. This was my first lesson that to understand a delusion you have to join it for a while.

We grabbed the air and swiped at the walls. I put an arm around his shoulder and we staggered our way back to his room. The smiling nurse opened the window and we emptied our hands into the warm summer night. After standing at the window a few moments, Mr Brad sighed, then laid back on his bed.

“We’ll call you again, Jack,” said the nurse.

“Who do you usually call?” I asked.

“Generally Buck, the regular evening orderly, but he’s busy in the ER with a really wild guy. Have you met him?” she asked.

“No, but I hear he’s good.”

“Yeah, good, but real quiet and tough. He was a prisoner of war for over a year in Korea. Not a man to cross,” she replied.

One Friday night, my mom needed the Corvair for a girls’ night out. Dad’s new Impala was not then or ever available. I thought perhaps I’d miss a night’s work, maybe even enjoy a summer date.

“I’ll drop you off at the hospital. You can find a ride home.” Dad didn’t expect or tolerate opposing views.

On a late-night coffee break, I sat down at a table with Buck, who was sitting alone drinking black coffee. He was my height at 5’10,” and 180 pounds of solid muscle. He wore a white t-shirt under green scrubs. His face was lined and serious as he nodded to me when I sat down. We ate donuts and sipped coffee for awhile; I was used to strong, silent men. My Dad and brothers never minded quiet and considered conversation during hockey or football games as odd.

Finally, I offered an opening. “Busy night.”

“The usual,” he replied.

“I heard you were in the service?” I asked.

“Army.”

“Korea?”

“Yup.”

“How was it?”

“Terrible, Kid. Don’t talk about it much.”

“Did you learn anything over there, Buck?”

He thought for awhile. “Yeah, one thing Kid: never show fear. They feed on it. Make them think you can always come at ‘em.”

“Think I could get a ride home tonight?”

“Where to?”

“Bloomfield Hills. On Gilbert Lake.”

“Stomping in the high cotton, kid. But yeah, sure, come get me at eleven.”

Eleven came around quickly, and we walked out to Buck’s immaculate old Buick. The chrome sparkled. Buck rubbed a faint smudge off the deep blue hood. We drove out onto Woodward Avenue. Traffic was light and the night dark, without a moon.

About halfway home two motorcycles passed us and two more pulled in behind us. The lead biker slowed, then pulled us over to the side of the road. The riders dismounted and ambled over to the driver’s side window. I sensed real danger.

The riders were 1950 hoods. They had long dark hair slicked back with hair oil. They each sported black leather jackets, tight jeans and a condescending scowl. Buck rolled the window down.

“Nice car, old man,” said the lead hood. Buck reached underneath the dash and pulled out a large, loaded service revolver. He rested the pistol on his outstretched arm, now pointed at the lead hood’s face. The big Buick engine purred in the quiet night.

The hood stared at the revolver, then at Buck, and said, “I’m sorry man, I thought you were alone.”

Buck kept the revolver aimed at the hood’s head as he sauntered back to his bike, started the engine and drove off.

We didn’t talk the rest of the way home. I thanked him for the ride and wondered if a doctor’s life would always be so dramatic.