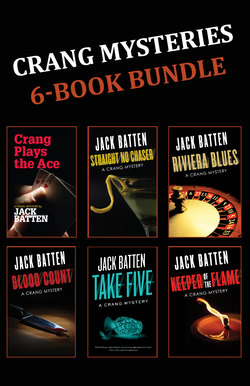

Читать книгу Crang Mysteries 6-Book Bundle - Jack Batten - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

MATTHEW WANSBOROUGH was saying he was sorry to be where he was. He was in my office.

“I’m embarrassed to have to come here, Mr. Crang,” he said. “That’s unfair to you. I apologize.”

“Save the apology,” I said.

Wansborough let out a small smile.

“You may not need it,” I said.

The smile widened a fraction.

“Second thought,” I said, “hold the apology in reserve. I know you at second hand, and far as I’m aware, you don’t know me at any hand.”

Wansborough made a clearing noise in his throat. He was in his mid-fifties and had grey hair like Gary Grant’s and wore a deep blue custom-tailored three-piece summer suit. Six hundred dollars, I’d say, Holt Renfrew. Wansborough had phoned that morning for an appointment. I knew his name from Zena Cherry’s column in the Globe and Mail. Zena writes with affection about the fun times of people around Toronto with old money. She mentions Matthew Wansborough about once a month. Zena says he likes to ride to hounds.

Wansborough said, “I’ve come because my people said you were the counsel who might assist me.”

“That’s a good start. Who are your people?”

“McIntosh, Brown & Crabtree. They look after my legal affairs.”

“I’ll just bet they do.”

McIntosh, Brown & Crabtree is number one or two among the big law factories in the bank towers along King Street. It has 150 lawyers and another 275 people in support personnel, which is what big law factories along King Street call paralegals, title searchers, articling students, computer operators, and other lesser legal folk.

I said, “Tom Catalano in the litigation department down there give you my name?”

“He spoke well of you,” Wansborough said.

“Hey, hold him to it.”

“Mr. Catalano didn’t say what sort of people you ordinarily represent, Mr. Crang.”

“Mostly guilty people,” I said. “Break and enter, drug charges, sometimes a bank holdup, the kind with guns. Paper offences are a mini-specialty of mine. You know, fraud.”

Wansborough was sitting on the client’s side of my desk. He had his left leg correctly crossed over his right. He was showing a bit of blue silk sock and a lot of sturdy black Dacks oxford. He recrossed his legs, right over left, lifting his pant leg by the crease with thumb and forefinger. He didn’t say anything.

“My people are usually guilty,” I said. “But sometimes they’re not guilty of what the police charge them with. It’s a matter of degree. The police say manslaughter, the evidence says a variation of assault. Or maybe there’s bad identification of my client. Or maybe the police knocked him around and he talked more than he intended. These things come out when I get a chance at cross-examination in court.”

“You make it sound matter of fact,” Wansborough said.

I said, “It’s what I’m good at, asking questions in court. Outside court too. I’m nosy.”

Wansborough pursed his lips. Maybe he didn’t approve of my clients or my office or, heaven forbid, my clothes. I had on jeans, a light blue broadcloth shirt, and a pair of Rockport Walkers with spongy soles. It was my uniform on days I wasn’t scheduled for court. On days I had a case on, I looked downright spiffy, gown hanging from my shoulders without an undue wrinkle, vest free of mustard stains, tabs and dickey snow-white from the laundry. The model of a criminal lawyer. My office had a wooden desk, a swivel chair on the business side of the desk, three chairs like the one Wansborough was sitting in on the other side, a green metal filing cabinet, and bookshelves that held bound volumes of Canadian Criminal Cases going back to 1912. It wasn’t listed on a tour of notable offices of Toronto. Or maybe Wansborough’s lips were always pursed.

“Have we got to the part where you’re embarrassed?” I said.

Wansborough plunked both Dacks on the floor. Decision time.

“It comes to this, Mr. Crang,” he said. “I am showing more profit than I ought to be doing.”

“Some people that happens to, Mr. Wansborough, and nobody calls it trouble.”

“I manage the family’s business interests,” he said. “They’re extensive, and I have maintained us at a steady profit even in the economy’s downturn. I invest in companies whose management is familiar to me. I know the people and the corporate performances.”

“That ought to get you a profile in Canadian Business,” I said.

“I hold seven directorships,” Wansborough continued. “In six other instances, with smaller companies, I have a controlling interest.”

I swivelled a few degrees to the left in my swivel chair and looked down into the street. A kid was walking by. From my angle, the top of the kid’s head looked like a Walt Disney skunk. Pinkish-white stripe down the middle, jet black on the sides. My angle was straight down from the second floor over a unisex clothing store called Trapezoid. The office I practised out of was on Queen West near Spadina. When I moved in a dozen years ago, it was working-class commercial and heavy on Middle European shopkeepers. A few years back, in some unfathomable shift of Toronto custom, the street went New Wave. It was farewell to the Czech ma-and-pa hardware store and the goulash restaurant. Now it was science-fiction bookstores and diners that charged three dollars for café au lait. I didn’t mind the change. It could have been worse. It could have been a Burger King and porno shoppes.

Wansborough paused in his business catalogue.

“Mr. Crang,” he said, “mightn’t it assist us in the long run if you take notes?”

“That what you’re used to at McIntosh, Brown?”

“A junior attends the meetings and records pertinent details, yes.”

“One, Mr. Wansborough, I have no junior in residence, currently or ever. And, two, you ever see The Thirty-Nine Steps? Old Hitchcock movie?”

“I recall reading the novel at school. Didn’t Lord Tweedsmuir write it?”

“I’m Mr. Memory.”

“Pardon?”

“The guy in the movie who remembers everything or, if you prefer, in the book. Mr. Memory. That’s me. Mind like a steel trap. Nothing escapes. Trust me.”

“I see,” Wansborough said.

“He was John Buchan when he wrote the book,” I said. “Lord Tweedsmuir was.”

Wansborough cleared his throat again.

“The information I’ve given you,” he said, “is in the nature of background. I want you to understand that my investment in a company called Ace Disposal Services is a departure from my customary practice.”

I said, “Ace Disposal doesn’t sound like it ranks up there with the blue-chippers.”

“I’m aware of that, Mr. Crang.”

Wansborough’s voice had a snap to it. For all his prissiness, he didn’t strike me as anybody’s pushover. When he rode to hounds, I’d put my money on him as first rider to the fox every time. He had a squared-off face and jutting eyebrows and he was as tall as I, five eleven or so, and heavier, over two hundred pounds. I’m built along the lines of yon Cassius. Lean and hungry.

“What about the aberration, Mr. Wansborough?” I said. “Why Ace Disposal? And what is an Ace Disposal?”

“The investment was to show support for my cousin,” Wansborough said. “I advanced $300,000 four years ago last February. My cousin wished to buy into a company as a working partner and chose Ace Disposal for the purpose. The investment made the family a minority shareholder and obtained my cousin a vice-presidency. Ace’s business, as far as that is concerned, is in transporting waste from construction sites to municipal dumps. Its assets consist of a great many large trucks and a maintenance area here in the city. In the first two years after my investment, the company showed negligible profits, as I rather expected would be the case. Beginning in the second quarter last year, however, it has yielded what I consider a disproportionately high profit. That puzzles me.”

“Let’s go back to your cousin,” I said. “What’s he have to say about the new bonanza?”

“She, Mr. Crang,” Wansborough said. “My cousin is Alice Brackley. On my mother’s side. She attributes the change to improved management. My cousin, I tell you this in confidence, has been the difficult member of the family. Intelligent enough for a woman but terribly stubborn. I believe she went into Ace Disposal to show she was as competent in business as any of the men in our family. Especially into such a business as Ace Disposal.”

I said, “Headstrong.”

Wansborough liked that. He said, “One doesn’t hear such an adjective these days.”

“One doesn’t.”

Wansborough said, “The change for the better in the company coincided with a new group purchasing a majority interest. A man named Grimaldi has been president for the past twenty months.”

“Fine old Monacan name.”

“That would be another branch of the family,” Wansborough said. The snap was back in his voice.

“Mr. Grimaldi has an expansive charm,” he said. “I concede that. And his operational manner is aggressive. He keeps the trucks on the road six days a week, that sort of thing. Charles is Mr. Grimaldi’s first name, and certainly my cousin praises his person and his methods. But he is in my view evasive when I inquire into the company’s recent success. So is Alice. I have never read the company books.”

I swivelled around to face Wansborough and put on my summing-up look.

“What we have here,” I said, “is an outfit doing better business than you think it should and an executive officer who isn’t to your taste.”

Wansborough’s head made a brusque nod.

I said, “ And you’re retaining me to ease your mind about both.”

Another nod. I was a whiz at synthesizing information. I said, “At the worst, you want to know if there’s hanky-panky.”

Wansborough said, “Mr. Catalano said you have had previous experience in the sort of inquiry we’re discussing.”

“Tom’s talking fraud,” I said. “One of McIntosh, Brown’s corporate clients, big printing firm, it developed a leak in its treasury. The company was coming up a few hundred thousand short and nobody could find the hole. Catalano hired me to poke around on the quiet. Turned out the two women at the top of the accounting department, longtime employees, much beloved by all, were running a sweet racket. They invented employees on paper. Gave them names, social security numbers, bank accounts. Put them on the tax roll, handed out T-4s, filed their income tax returns in the spring. And every week they issued pay cheques to the employees’ bank accounts. Except the employees were paper people and the two old darlings ended up with the cash.”

Wansborough’s lips did their pursing number.

I said, “In accounting parlance, that’s called a dead-horse fraud.”

Wansborough’s face looked tight.

“Don’t take it as a precedent,” I said. “Your problem doesn’t sound in the same league.”

I couldn’t tell whether I’d reassured Wansborough. He left the office and I watched him from my window. He was walking east on Queen behind a girl with a haircut I’d last seen on William Bendix in Wake Island.