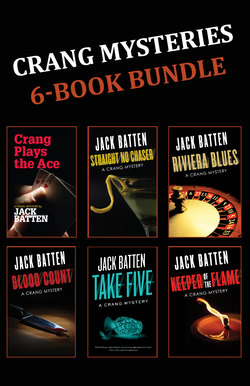

Читать книгу Crang Mysteries 6-Book Bundle - Jack Batten - Страница 52

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

18

ОглавлениеTHERE WAS A BOWL of five-day-old homemade chili in the refrigerator. The home it was made in was mine. I peeled back the Saran Wrap that covered the bowl, and sniffed. My nostrils didn’t shrivel, and no blue mould lurked at the bowl’s edges. I scooped the chili into a pan, and put the pan on the stove at a low heat.

On television in the living room, CBS was showing U.S. Open Tennis. Ivan Lendl was playing. When wasn’t Ivan Lendl playing? I had a vodka and soda and the Harold Town catalogue. The Great Divide was reproduced in its whites and greens near the front of the catalogue, and on the opposite page there was an explanation of the picture. It said Town took his first plane flight in 1965. He was in his forties, and the experience of looking at the world from the new perspective of straight down blew him away. He went home and painted The Great Divide. It was his interpretation of a telescoped view out of the window as the plane came over the runway at the end of a night flight. Nice guess, Crang, fissure in the rock. Not even close.

I turned the catalogue’s pages, and on television the tennis match went on. By and large, tennis makes genteel noises. The light thonk of the ball coming off the racquet, the polite handclapping between points, the referee’s moderate tones. The occasional roar of planes heading into LaGuardia Airport near the U.S. Open stadium was a pain in the eardrum, and the now-and-then hollers from yahoos in the stands. But mostly the background tennis sounds seemed about right for a browse through the Town catalogue. After a while, I ate the chili.

At ten past three, the doorbell rang. The young man on the front step looked like he’d just been let out of Sunday school. He was wearing a light single-breasted black suit, white button-down shirt, and a tie that was so discreet I couldn’t tell whether it was black or deep purple. He said he was present on an errand for Mr. Charles, and handed me a large brown envelope.

“You haven’t been inconvenienced, sir?” The kid had taken lessons in earnest from Cam. “I was supposed to have this to you at three.”

“Just listening to tennis. No inconvenience.”

“Of course, Mr. Crang. Thank you, sir.”

The kid didn’t kiss my hand. No one’s faultless.

I opened the brown envelope at the kitchen table. There were two single sheets and a bunch of other papers clipped together. The top sheet dealt with Raymond Fenk. Ha, he had a record. Not much, but a record. Two convictions in California for possession of an illegal drug. On both, he’d been charged with trafficking but pleaded guilty to reduced counts of simple possession. Must have had a defence lawyer who was a winner at plea bargaining. Fenk paid a fine on the first charge and did ninety days on the second. The drug in question was described on the sheet of paper in formal laboratory language. But, scraping away the Latin and the chemistry, we were talking cocaine.

The second sheet was headed “Trevor Dalgleish Clients”. These had to be the people Cam thought Trevor might be romancing. Ten names altogether. The first six were separated by double spaces and had complete addresses and phone numbers after them. None of the names rang bells. The other four names were grouped and had one address for the lot and no phone number. Nho Truong. Dan Nguyen. Nghiep Tran. My Do Thai. I was in business. The names were Vietnamese. Were any of them matches for the two names I saw on Saturday afternoon? Written above Trevor’s name on the press release for Hell’s Barrio? In Fenk’s hotel room? My memory was okay, but not photographic.

The address for the four men put me on more solid ground. It was an Oxford Street number. Oxford ran off Spadina Avenue south of College. It was in the Kensington Market area. Portuguese fish stores. West Indians peddling live chickens and rabbits and ducks. Fruit and vegetable stalls on the streets. Annie and I did monthly excursions to the market for provisions. I don’t think we’d run into Nho Truong and the guys. Hadn’t bought a live duck either.

The papers clipped together were publicity blurbs, cast listings, and other informative bumpf on six movies. Hell’s Barrio came first. Raymond Fenk’s name was front and centre as producer. I didn’t recognize the names of the rest of the Hell’s Barrio people: the actors, director, cinematographer, the best boy. On the other five movies, my recognition quotient was a total zip. The people who made the movies had names that meant nothing to me. Neither did the movies’ titles. All I knew was, the same guy was in charge of lining up the six for the Alternate Festival. Trevor Dalgleish.

Was there a common thread in the six? Hell’s Barrio, I already gathered, was about Hispanics having it tough in L.A. The second movie was about AIDS. I couldn’t tell from the literature whether it was feature or documentary. Next was a film “as relevant as today’s headlines and just as explosive”, the publicity said, about black street gangs in a city that wasn’t identified. Hispanics, AIDS, and gangs? So far, not much of a common thread. People who weren’t getting a kick out of life? Maybe film analysis wasn’t my long suit.

My vodka and soda was empty. This seemed to be a job—figuring out what the six movies shared—for the in-house film critic. If I asked Annie to take a shot at it, I’d have to go all the way. Tell her everything that had gone on: the tail job for Dave Goddard, Fenk’s murder, the rest. Well, I was due to let her in on the events to date. Overdue. Then she could look over the six movies for points in common. She could also tell me what the hell a best boy was.