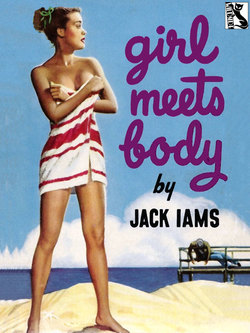

Читать книгу Girl Meets Body - Jack Iams - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

Do Not Disturb

Tim Ludlow’s war bride, the former Sybil Hastings of London, poked her head into the bathroom of their hotel suite. “There’s a tap marked ice water” she said. “There really is.” Tim heard a squish. “And it really is ice water, too. For dousing the head, I suppose, on bad mornings.”

“Most people just drink it,” said Tim.

“Oh,” said Sybil. She wandered back into the austere pink and green sitting-room. Its windows, between stiff draperies, were blurred and gray with the late October drizzle. “Darling,” she said, “would you think me frightfully ungrateful if I suggested that ice water is the last thing in the world I feel like drinking?”

“There was supposed to be something else,” said Tim. He looked at his watch and made a fidgety move toward the phone. Soft footsteps and a cheerful clinking sounded just then in the corridor, followed by a discreet knock. “Here we are,” said Tim with relief. “Come in.”

A bellhop, grinning like a bellhop in an ad, pushed a wagon into the room. Pale goblets trembled on it beside a sweating silver bucket.

“Tim, darling!” cried Sybil. “Champagne! There’s nothing in the world I like better!”

“Nothing?” said Tim.

She gave him a mocking glance. “Well, there’s bridge.” Then her dark eyes widened a little. “Blimey, I’ve married you without asking if you play bridge.”

“Seems to me the registrar asked me.”

“So? And what did you say?”

“Same thing I said to the rest of his questions. I do.”

“Thank God for that,” sighed Sybil. “I’ve always thought the ceremony should include something about never taking this, thy partner, out of business doubles.”

The bellhop cleared his throat. “Where’ll I put this?” he asked.

“Oh, anywhere,” said Tim.

“Anywhere indeed!” said Sybil. “Wheel it into the bedroom, laddy.”

The bellhop’s grin grew broader, almost, thought Tim, to the point of impertinence. Actually the bellhop, who was fifty and had fallen arches, was indifferent and bored, his grin a calculation in dollars and cents. He had thought there might be five in it, and his thanks for the dollar Tim gave him were tepid.

Tim stared after him in momentary annoyance, then he stared at the bedroom door which Sybil had closed behind her. He wasn’t sure if he was supposed to wait or knock or barge in or what. He wasn’t very sure about anything. It was more than two years since he had seen Sybil, and this day, to which he had so long looked forward, had brought with it a sudden sense of uncertainty. There had been hours of waiting on the chill, damp pier for the bride ship—a callous phrase, like cattleboat, yet pagan and exciting, too. There had been the palaver with customs and newspapermen that shattered the emotional intensity of meeting. Together at last in a taxicab, they had listened through one rain-dreary street after another to a discourse by the driver on the merits of Notre Dame. (“Is he talking about priests?” Sybil had whispered. “Neophytes,” said Tim.)

Even during their first few minutes alone in the hotel, Tim continued to feel much as he once had when a German colonel unexpectedly surrendered to him. However, things had worked out all light on that occasion, and he hoped and trusted that they would again.

“Tim, sweet,” called Sybil from the bedroom, “have you seen my medal?”

“No,” said Tim, frowning at what struck him as an incongruous subject. “I didn’t even know you had a medal.”

“I got it for driving you around so nicely. Come in and see it. I have it on.”

“All right,” said Tim.

“Incidentally,” she added, “it’s all I do have on.”

Tim gulped and took a quick, happy look at himself in the mirror. He straightened his tie. “I hope it’s not the kind that pins on,” he said and went into the bedroom.

* * * *

Tim and Sybil didn’t really know each other awfully well. For the first few weeks of their acquaintance, she had been merely one of the several trim and efficient young ATS drivers assigned to a group of officers, including Tim, in the American Army’s Division of Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives, which was then waiting nervously, and a little sheepishly, for the invasion to open up its task on the Continent. Like Tim, who had been an instructor at a midwestern college, most of them had emerged, blinking, from the ordered tranquility of academic life into the crisp confusion of the Army and they were only too conscious of how unwarlike they were.

Among the ATS drivers, Sybil told Tim afterward, they were known as the Panzer Professors.

One night late in May, Sybil was driving Tim to his quarters from an officers’ club off Grosvenor Square when a buzz bomb cut out directly overhead. So it sounded, anyway, and so it almost was. In the moment of terrible silence that followed, when the wet, green smell of spring was sweeter than it had ever been before, Sybil turned suddenly toward the back seat and said, “Hold my hand, Captain. It’s going to be close.”

Even as he took her cool hand in his own, which was shaking as if it held dice, the earth exploded and, less than a hundred yards away, a geyser of debris rose and slowly fell, a good deal of it over the car. It was strangely soft debris, though. The bomb had landed among the flower beds of St. James’s Park.

“Jolly lucky hit, that,” murmured Sybil. “For us, I mean. Poor show for Jerry.”

Then she realized he was holding her hand and withdrew it. “Sorry about the display of nerves,” she said.

Tim tried to say something suitable, but his voice was missing. He was trembling still and conscious of very little outside of two facts: he was alive and his driver’s face in the unreal moonlight was white and beautiful. He leaned forward and kissed her. “Captain!” exclaimed Sybil, but she didn’t sound angry. “I believe that’s forbidden by the Articles of War.”

Tim’s voice came back. “Damn the Articles of War,” he said and kissed her again. In the distance, harsh and welcome, the all-clear sounded.

“Shall we be off, sir?” asked Sybil briskly.

“No,” said Tim. He leaned halfway across the back of the seat and took what he could reach of her in his arms. It occurred to him, dimly and unimportantly, that he must be presenting quite a spectacle to anyone approaching from the rear.

It also occurred to him, after he had gone to bed, that the only conversation he had contributed to the most romantic interlude of his life thus far had been a disrespectful reference to the Articles of War.

A few days later, on D-Day Minus One as it turned out, they were married, at Paddington Registry Office. A week after that, a week during which he scarcely saw his bride, he got his orders for the Continent.

“Are you scared, darling?” Sybil asked him the night before he left.

“Not of the enemy,” said Tim. “I probably won’t be anywhere near the enemy. But I’m good and scared of the American generals I’m supposed to keep from shelling cathedrals. Can you imagine me telling General Patton he’s got to change his line of fire?”

“Of course,” said Sybil. “Why should you be more scared of a general than I, a lance corporal, am of a captain?”

“I don’t expect to be in bed with any generals,” said Tim.

It was their last night together for a long, long time. Tim followed the armies through France and Luxemburg and into Germany, where the task of searching out and restoring the works of art picked up here and there by Hermann Goering and fellow connoisseurs lengthened past one V-Day and then another, deep into the turbulent months of peace.

For a lover of art, it was exhilarating work. To stumble unexpectedly upon a cache of Rubenses and Rembrandts gave Tim much the same sensation that a man of coarser tastes might have derived from stumbling into the Goldwyn Girls’ dressing-room.

But even when the excitement of the job was at its peak, the edges of his mind were frayed with loneliness for Sybil. And, later on, when the work settled down to the humdrum business of sorting, cataloguing, storing, and shipping, his longing for her turned into a constant ache. More tantalizing than the actual separation was the fact that he scarcely knew, and had scarcely loved, his wife. His colleagues, most of whom were older than his twenty-nine years, all seemed to have placid helpmeets who sat on American porches waiting for them and sent them snapshots of the children. Whereas Sybil was a figment of a dream, something he sometimes wasn’t sure had really happened.

She wrote to him, of course, but her letters, telling of her life among friends he had never met, against unfamiliar backgrounds, heightened his sense of distance from her. They gave him that feeling of disquiet that sensitive children get when they first realize their parents’ lives don’t center around the nursery.

His own parents wrote him letters that didn’t help. Between the congratulatory lines lurked midwestern suspicion of the foreign. What about her family, they wanted to know. And there wasn’t much he could tell them. All Sybil had ever mentioned was that she didn’t remember her mother, and her father had died just before the war started. There hadn’t been room for family discussions in the time at his and Sybil’s disposal. There had barely been room to eat. He had a notion that she came of genteel, possibly elegant, folk, but it didn’t bother him one way or the other when he was with her. Now, once in a while, it bothered him.

A thoughtful friend sent him an editorial from a Chicago newspaper, deploring overseas marriages. Ninety percent of these girls, it said right there in print, are out for what they can get. Tim utilized the editorial in the most fitting way, but sometimes, on sleepless nights, it would creep into his mind like a singing commercial and he would find himself brooding on possibilities that two minutes of Sybil’s companionship would have blown out the window.

The months dragged on. When he was finally released, he happened to be in the Tyrol and the simplest way home lay through Italy. He pulled all the wires he could to manage it via England, but he might as well have pulled dandelions. None of the Army’s channels led to England.

So it was that two and a half years after his marriage, he found himself in a New York hotel room with a tall, pale, intensely desirable stranger. He had a feeling that the house detective might knock at any minute.