Читать книгу Writing the Ancestral River - Jacklyn Cock - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1Motivations

Rivers have the power to connect us to nature, to our past and to our collective selves. They sustain life, inspire poetry and fire our imaginations. As the young sailor in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness expressed it, they carry with them ‘the dreams of men, the seeds of commonwealth, the germs of empires’.1 Conrad clearly had in mind the great river highways such as the Amazon, the Congo, the Mississippi, the Mekong, the Thames and the Yangtze. This book tells the story of what is in comparison a ‘little’ estuarine river, which nevertheless raises large questions.

This river, the Kowie, is not a major waterway and has not been the subject of any scholarly attention. While located in a war-ravaged frontier area, it was never an official frontier and it played a humbler role in South African history than the rivers which the colonial authorities used to mark the changing borders of the Cape Colony: the Bushmans, Fish, Keiskamma and Kei. The area was an open frontier until 1778, when the Fish was declared the official limit of the Cape Colony. Most importantly for this book, the Kowie River runs through the centre of the Zuurveld, the area first bounded by the Fish to the east and the Bushmans to the west.

This was an area of blending and mixing, a meeting point not only of river and sea, of fresh and salt water, but of very different people, identities and traditions that have shaped South African history: Khoikhoi herders, Xhosa pastoralists, Dutch cattle farmers and British settlers. Their interaction often involved intense and violent encounters and still today there are contesting claims and traditions relating to the land, the fertile sour-grass hills and plains of the Zuurveld, now known as Ndlambe Municipal Area, one of the poorest parts of South Africa.

The original inhabitants of the Zuurveld were the Khoikhoi, often contemptuously called ‘Hottentots’ by the settlers. These indigenous people were the first to experience what has been described as the ‘violent, even genocidal process’ of colonial expansion in the late eighteenth century as Dutch farmers appropriated their land, their cattle and their power. In 1774 the Dutch government at the Cape ordered that ‘the whole race of Bushmen and Hottentots who had not submitted to servitude … be seized or extirpated’.2 ‘By the end of the century there were no independent living pastoral Khoekhoe in the region.’3 It was from the Khoi language that the name of the Kowie River derives. The different names given to the river reflect changing constellations of power. According to the Dictionary of South African English, Kowie comes from the Khoi word qohi, which roughly means ‘pipe’, an image which could refer to the shape of the river. An early traveller, Ensign Beutler, described how the Khoikhoi smoked their tobacco with a water pipe. According to another authority, the river was called iCoyi, from a Khoi word meaning ‘buffalo’, which used to be numerous in the Kowie valley.4 In the Eastern Cape, ‘it is the rivers that have clung most tenaciously to their Khoi names: Kowie, Kariega, Kei, Keiskamma and Koonap’.5

Rivers like the Kowie were important in Khoikhoi identity. According to Ensign Beutler, whose expedition of 1752 passed through the area, the Khoikhoi ‘do not know of what people they are: they name themselves only after the rivers by which they live’.6 He also observed that before they ‘cross a big river, they first throw into it a green twig, with wishes to themselves for much luck, a multitude of cattle and long life. Afterwards they wash their whole body and then cross the river.’7

Although it is clear from Beutler’s journal that there were no Xhosa living west of the Keiskamma at the time of his 1752 expedition, the Dutch explorer Colonel Robert Gordon found many Xhosa living in the Zuurveld when he visited the area in 1777. By this time, Dutch trekboers, or pastoralists, were already encroaching upon Xhosa and Khoi territory, and within a few years the Zuurveld became marked by struggles over access to land and cattle. The clashes formed the start of what has been called a Hundred Years War between the Xhosa and the colonists, who, after the Cape was taken over by the British, could call on the support of the British army.

The thick bush of the Kowie and other river valleys was the scene of violent clashes during these wars of dispossession. At that time the riverbanks were thick with ancient cycads, wild crane flowers, gigantic yellowwood trees and shady white milkwoods. The dense vegetation, the thickly forested valleys and deep ravines, the towering trees, creepers and vines, all offered hiding places to the Xhosa, for whom this was a familiar landscape. It also made movement difficult for the British soldiers. During one war ‘the Gqunukhwebe showed what could be done with the river beds of lower Albany. Using the banks as parapets, they exposed only their heads … They were able to hide for long periods under water, their nostrils emerging under cover of the reeds at the river’s edge. Otherwise they hid in trees, in antbear holes and in caves.’8 The Kowie was one of the rivers used in this way.

As this history shows, the various groups living in the Zuurveld – Khoikhoi, Xhosa, Dutch and British – interacted not only among themselves but also with the Kowie River in different ways. As with the Khoikhoi, for the Xhosa rivers were geographical markers of identity. Moreover, the Xhosa believed they had sacred qualities. Traditionally Xhosa warriors purified themselves before battle by bathing in rivers. Rivers like the Kowie with their deep pools also provided access to the ancestors, the Abantu Bomlambo (People of the River), elusive water divinities who have the power to shape the lives of their descendants. Different pools of the Kowie River were, and are, especially good places for accessing the People of the River. They are believed to live beneath the water with their crops and cattle. Initiates who are called by the ancestors to become diviners go to the People of the River, who sanction their calling. In the millenarian Cattle Killing of 1856–7, according to legend, the People of the River emerged from the water to instruct the Xhosa to purify their contaminated homesteads. Today gifts for the People of the River are often floated out into the centre of river pools in small reed baskets containing items such as sorghum, tobacco, pumpkin seeds and white beads. I have seen offerings to the river people in beautifully woven grass baskets floating in the Blaauwkrantz pool, at the foot of the Blaauwkrantz Gorge, and in the pool that marks the confluence of the Lushington and Kowie rivers. These are places that feel holy and enchanted.

Researching the history of the Kowie has meant revisiting my own ancestors and engaging with their relationship with the river. This engagement is necessary because the ravages of the past continue in the present and, as Aubrey Matshiqi has written, ‘the lack of acknowledgement of what was done to black people during the colonial and apartheid eras is a recipe for social, political and economic calamity’.9

Acknowledging that past and the inter-generational, racialised privileges it established and perpetuated is one reason why this book is also a personal account of what the river represents to me. As the artist Louise Bourgeois wrote of her childhood, the river weaves ‘like a wool thread through everything’.10 For me, the Kowie River connects a personal and a collective history, the social and the ecological, the sacred and the profane, in both the honouring and the abuse of nature.

This book focuses on three very different moments in the river’s story which involved the linked processes of ecological damage and racialised dispossession. The Battle of Grahamstown, which was fought in the vicinity of the Kowie in 1819, changed the course of South African history by consolidating British control of the Zuurveld. In its aftermath, a settlement was established at the mouth of the Kowie River, known as Port Kowie, though it was soon renamed Port Frances by settlers anxious to win favour with the Cape governor, Lord Charles Somerset, whose daughter-in-law was called Frances. Subsequently, it was given yet another name by settlers eager for government support for development of the harbour – Port Alfred, in honour of the British queen’s second-eldest son, who toured South Africa in 1860. As the prince chose to go elephant hunting instead of attending the ceremonial renaming of the town, my great-aunt Harriet Cock, then aged 8, deputised for him.

It is the harbour, begun at the river mouth in 1821 and extended and altered through to the 1870s, that forms the second ‘moment’ of the Kowie River’s history explored in this book. The establishment of the harbour helped draw the former Zuurveld region tightly into the trading and commercial networks of the British empire, and contributed in this way to the subjection of the Xhosa within colonial society.

The third moment of my story is the development of an upmarket marina at Port Alfred in 1989. This project has undermined the ecological integrity of the river and at the same time has highlighted and entrenched even further the longstanding divisions in the area between white privilege and black poverty.

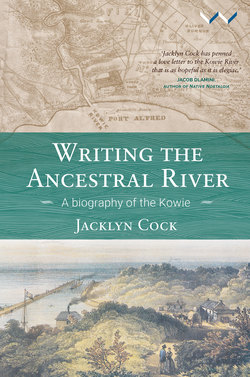

Writing the story of the Kowie River has been more than an intellectual engagement. It is both a memoir and a paean to place, a love story disguised as a social and environmental history. When we talk of a ‘love of place’, Rebecca Solnit points out, we ‘usually mean our love for places, but seldom of how the places love us back, of what they give us. They give us continuity, something to return to, and offer a familiarity that allows some portion of our own lives to remain connected and coherent. They give us an expansive scale in which our troubles are set into context, in which the largeness of the world is a balm to loss, trouble and ugliness.’11

The Kowie River has given me a great deal. I love the rich prawn smell of the mud banks exposed at low tide, the banks of euphorbia trees, the deep green pools where catfish, giant kob and grunter still live, and the surging tide where the river enters the Indian Ocean. To use the words of the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, ‘we return to the banks of certain rivers’,12 and since infancy there has never been a year when I have not swum in the green-brown waters of the Kowie River, walked its wooded banks or spent hours watching the surge of the tide and the crashing waves as it empties into the sea. In all of these ways – canoeing, swimming, fishing, birdwatching, picnicking or simply sitting on its banks watching the light change – the Kowie River has been a constant thread, a source of renewal of energy and purpose for over seventy years of a tangled life. Going to ‘the Kowie’ became a kind of pilgrimage, a place to journey to receive the river’s spirit and be nourished.

In relation to the lagoon adjoining the east bank of the river, this pearly haze of happy memories is infused with a sense of loss. Like many other local children, I learned to swim in the shallow waters of the lagoon, to drive a car on the lagoon flats and to dance in the adjoining café. This lagoon and an adjoining salt marsh no longer exist. The complex architecture of the salt marsh, a maze of channels kept clear by the sluicing action of the tides, has now been obliterated, replaced by a marina, an exclusive gated community of luxurious houses, many of them holiday homes. In the 1950s, when I grew up, Port Alfred was a very different place, a little fishing village where a horn would blow to signal a catch of fish from the returning boats, fresh produce at the market or the escape of a ‘lunatic’ from the mental hospital below my parents’ house. But the Kowie River and the little town on its banks remain for me a site of density and depth, a connection to ancestral shades and a web of social bonds.

For a long time I have cherished the ambition to traverse the seventy kilometres from the source of the Kowie River to the sea. This ambition to walk and canoe the entire length of the river is inspired by various accounts in river literature. One of the historians of the Thames, Frederick Thacker, maintained that to appreciate ‘the ancient and unspoilt countryside’ you must ‘traverse its roads upon your own feet and pull and steer your craft along its winding reaches with your own arms’.13 Another inspirational example on a grand scale is Jeremy Seal’s attempt to follow the Meander in Turkey for five hundred kilometres from its headwaters at Dinar to the Aegean with his collapsible canoe.14 Another intrepid adventurer was Phil Harwood, who braved crocodiles, giant snakes and angry locals to become the first person to canoe the Congo River from its source in a tiny spring at the base of a banyan tree in the highlands of Zambia until it finally enters the ocean five thousand kilometres away.15

I have drawn on a rich river literature, from T.S. Eliot’s Thames in The Waste Land, (so different from the Thames of Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows), Paul Horgan’s Rio Grande, James Joyce’s Liffey, Alan Moorhead’s and Robert Trigger’s Nile, Joseph Conrad’s and Tim Butcher’s Congo, Mark Twain’s Mississippi, Charles Dodgson’s Isis and Joan McGregor’s Zambezi, to mention a few works with which I am familiar. Most scholarly is Simon Winchester’s journey down the Yangtze in The River at the Centre of the World. I was moved by the redoubtable Isabella Bird’s account of her voyage through the Yangtze Gorge and fascinated by Peter Ackroyd’s description of the 250-mile length of the Thames, though the short distance I’ve managed walking along a well-signposted Thames path with cows and green fields could not have been more different from my home experience. I was also inspired by Olivia Laing’s account of her walk along Virginia Woolf’s river, the Ouse, in which she drowned herself. This book is a wonderful account of how history resides in a landscape. I could identify with Laing’s feelings for the Ouse, the ‘river I’ve returned to over and again, in sickness and in health, in grief, in desolation and in joy’.16

Following the course of the Kowie through what used to be the Zuurveld and trying to access the ‘deep history’ of the area is also troubling because of my knowledge of what has occurred there, of earlier calamities. As Robert Macfarlane has written of walking through areas of Scotland subjected to the Highland Clearances: ‘The pasts of these places complicate and darken their present wildness … To be in such landscapes is to be caught in a double-bind: how is it possible to love them in the present, but also to acknowledge their troubled histories?’17 At the same time as the Clearances were taking place, the indigenous Xhosa people of the Zuurveld were being driven from their homes and subjected to the same violent process of dispossession as the Scottish crofters. So researching this book has forced me to acknowledge the ‘double-bind’.

Yet, if one can banish these ghosts of the past, the Kowie River catchment (the area of land drained by the river) is a colourful place. In summer the landscape is bright with the scarlet flowers of the coral tree and the pink blooms of Cape chestnut trees. In winter whole hillsides are ablaze with thickets of orange aloes, as well as the crane flower. Orange is the iconic Zuurveld colour, as it is also the colour of the traditional Xhosa dress dyed by using local clay.

Over the years I have explored much of the Kowie by foot or canoe. This was generally marvellous fun, though bad timing sometimes meant canoeing against the wind and tides, and traipsing through dense thickets of bush. The banks of the Kowie are lush in places with giant yellowwood trees and cycads, but elsewhere it is flanked by scrub and thornbush. It is not a showy, dramatic landscape. On one occasion I nearly trod on a cobra but its warning hiss saved me. Another time, in a stupid moment of exhaustion I lay down on my back under a milk-wood on the grassy riverbank and was instantly covered by an invasion of tiny ‘pepper ticks’. Once I set out with two intrepid friends to walk a stretch of the river north of Bathurst from Penny’s Hoek to Waters Meeting. This involved wading across the river (with the fast-flowing water waist-high) and fighting through reeds which stretched over our heads. We stopped frequently to keep our strength up with chocolate biscuits and tea made on a tiny gas stove. Though we carried Google Earth maps of the area, we argued endlessly about our exact location and eventually turned back. Given that our ages varied from 65 to 71 and between us all we were taking medication for high blood pressure, cancer, high cholesterol levels or diabetes, the attempt was a sort of geriatric heroics.

To find the source of the Kowie, I needed the help of a geographer. We eventually located it in a patch of dense indigenous forest in a ravine in the hills surrounding Grahamstown, called Featherstone Kloof. This muddy, leaf-choked spot is not a dramatic birthplace. There was none of the sense of mystery and power sometimes reported of springs and river sources in classical mythology. As Olivia Laing wrote of the Ouse, ‘there was no spring. The water didn’t bubble from the ground … “the source” sounded a grand name for this clammy runnel.’18 But I understood Robert Twigger’s ‘sense of contentment’ as he glimpsed ‘the small puddle in the middle of the jungle in Rwanda’, the spot earlier explorers had decided was the ‘real, true source of the Nile’.19 At the time we made our discovery near Grahamstown, it was an extraordinary thought that the thin, brown trickle of water could transform itself into the tumultuous river which at its ocean mouth has caused fishermen to drown and boats to overturn.

So why should we be concerned about this little river? There is nothing grand or magnificent about the Kowie, though its beauty has been recorded by artists such as Thomas Bowler, Frederick I’Ons and Marianne North. David Harvey answers the question: ‘In the broad scheme of things, the disappearance of a wetland here, a local species there and a particular habitat somewhere else may seem trivial as well as inevitable given the imperatives of human population growth, let alone the continuity of endless capital accumulation at a compound rate. But it is precisely the aggregation of such small-scale changes that can produce macro-ecological problems such as global deforestation, loss of habitat and biodiversity, desertification and oceanic pollution.’20 This book shows how the Kowie River is implicated in such social, political, economic and ‘macro-ecological problems’.

What did the Kowie River area look like in the past? Who were the original inhabitants and how did they live? Who was the Khoikhoi leader Captain Ruyter? Who were Makhanda and Ndlambe and what happened to them? When did the early European travellers – men like Le Vailliant with his plumed hat and his pet baboon and William Burchell with his fifty reference books, his flute and Khoi servants – visit this area and what did they think of it? What role did the 1820 settlers play in the region and, in particular, one of their number who was my great-great-grandfather William Cock? How important was the Kowie River to the development of the Eastern Cape? In recent times, was the breaching of the riverbanks to establish a marina a pioneering model of sustainable growth providing employment for a desperately poor community and making increasing revenue from rates available for development? Or was it a form of ‘ecocide’, which involved the destruction of a significant wetland and damaged the river irreparably? Both the harbour and the marina were established in the name of ‘development’, but did the benefits extend beyond a wealthy elite? These are some of the questions this book addresses.

* * *

Sitting quietly at places like the confluence of the Kowie and Lushington rivers, or canoeing or walking through the riverine forest, involves encounters with wild nature. One can hear the lap of the tide, and perhaps the bark of a bushbuck or the coughing sound of a baboon. Birdsong is constant and might include the sweet notes of the Black-headed Oriole, or the harsh alarm call of the Knysna Loerie, flying away with its scarlet underwings flashing, or even the soft hooting of the shy Narina Trogon. There are kingfishers and rare waterbirds like the African Finfoot and the Green-backed Heron. These birds are our access to nature, to the wild and the pristine. I have watched Cape Clawless Otters at play in a gold dawn light. These are very intimate and privileged experiences of wild nature. They give us the space (both psychic and geographical) to think about our place in the world and our relations with the wild creatures with whom we share it. They can remind us of our place in nature, of our ecological interdependence, even of our dependence on the trees which release the oxygen that allow us to live. They can provide us with a sense of joy, ‘an intense happiness’.21 Olive Schreiner wrote of ‘that strange impersonal peace that comes into our hearts when we contemplate nature’.22 It can also involve focusing and simplifying our lives. Henry David Thoreau believed: ‘in Wildness is the preservation of the World’.23 For him, walking (‘sauntering’ he called it) was the best way of connecting with nature. In a spirit of pilgrimage, I visited Walden Pond in Massachusetts where Thoreau lived, but today, filled with crowds and cars, Walden is a very different place.

Just as Walden Pond represented the world for Thoreau, the Kowie River embodies much of what I care about. So writing this book has involved three kinds of journeys: firstly, intellectual in the research process, which has involved many conversations and interviews with very different people as well as solitary hours in archives and reading rooms trying to trace the history of the area and understand its earliest inhabitants – the Khoikhoi, Dutch, Xhosa and British. Secondly, it has involved many physical journeys down the river, from its rising near Grahamstown to its Indian Ocean mouth, often retracing well-loved bays and places. Both these journeys of exploration have been fun. But the book has also involved an emotional journey, which has raised some unsettling questions about my own ancestry.

One of the British 1820 settlers was my great-great-grandfather. In my family he was always referred to as the Honourable William Cock, the name spoken in deferential tones, as if the title signalled more than membership of a discredited colonial institution, the Legislative Council, whose members were appointed by the governor of the Cape Colony. In these family conversations he was invariably described as an entrepreneur, and his efforts to turn the Kowie River into a productive harbour were always framed as a heroic confrontation with the forces of nature. It was therefore deeply shocking for me to read of him in recent historians’ accounts as a member of a settler elite who promoted the violent dispossession of the land and livelihoods of the indigenous population. Was William Cock a warmonger and profiteer, ‘the army butcher’ as the historian Timothy Keegan describes him? Was he one of the ‘strangers to honour’, as Noël Mostert terms the 1820 settler elite, or a brave pioneer and entrepreneur? The developer of the Port Alfred marina told me, ‘William Cock is the father of the marina. We could not have done it without him.’ This book will show that there are similarities in the two main assaults on the integrity of the Kowie River: the nineteenth-century harbour and the modern marina. Both are linked to a process of racialised dispossession originating in the violence of settler colonialism.

Obviously I found it painful to consider my revered great-great-grandfather as part of an imperialist settler elite driven by narrow commercial interests at best, a warmonger and profiteer at worst. But this was not the only unsettling discovery about my own family during the course of researching this book. I used to love working in the heavy, comfortable silence of museums and reading rooms. But the sense of peaceful engagement with the past was shattered in a particularly uncomfortable discovery one day. Going through old papers in the reading room of the Albany Museum in Grahamstown, I came across a letter which contained a reference to my mother, for whose intellect and integrity I had great respect. The writer stated, ‘I have come to the conclusion that Mrs Pauline Cock is a very unreliable source of settler history. What she doesn’t know she simply invents.’ Part of what she ‘invented’ was a consoling narrative held by many descendants of the 1820 settlers who still live in the Kowie area, one that tends to idolise the courage and enterprise of the settlers and praise the extension of the benefits of British civilisation to the benighted Xhosa.

Rivers can connect us not only to nature, from which many urban people are alienated, but also to questions of justice. Understanding that we are all part of nature in the food we eat, the water we drink and the air we breathe means recognising both our ecological and social interdependence and our shared vulnerability. Furthermore, rivers can connect us to our past and show how it is inscribed in the present. Researching the Kowie River has involved revisiting my own ancestors and confronting the inter-generational privilege which forms part of their legacy. This has meant confronting many prejudices, myths and distortions, which this book describes.

My story of the Kowie River acknowledges how the ravages of the past continue to flow through the present. It is a story that incorporates both social and environmental injustice: the silting and pollution of a river and the violent conquest of the indigenous Xhosa whose descendants continue to live in poverty and material deprivation.

But around the world people are increasingly reconnecting with nature and justice through rivers. Unlike other bodies of water, such as dams, oceans and lakes, rivers have a destination and we can learn from the strength and certainty with which they travel. I believe this learning is valuable because acknowledging the past, and the inter-generational, racialised privileges, damages and denials it established and perpetuates, is necessary for any shared future.