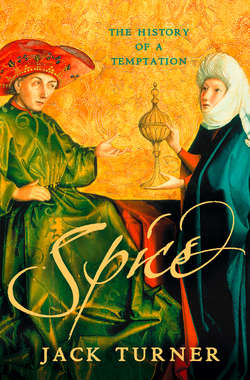

Читать книгу Spice: The History of a Temptation - Jack Turner - Страница 10

Christians and Spices

ОглавлениеAfter the year 1500 there was no pepper to be had at Calicut that was not dyed red with blood.

Voltaire, Essai sur l’histoire générale et sur les moeurs et l’ésprit des nations, 1756

Outside his native Portugal, where past glories live long in the memory, Vasco da Gama has generally been remembered as Columbus’s less eminent contemporary. It is a somewhat unfair assessment, for in a number of senses da Gama brought about what Columbus left undone. In sailing to India five years after Columbus sailed to America, da Gama found what Columbus had sought in vain: a new route to an old world. The one might be thought of as the complement to the other, as much in terms of the objectives as the achievements of their missions. Between the two of them, however dimly sensed it may have been at the time, they united the continents.

The greatest difficulty of Columbus’s voyage was that it was unprecedented. In navigational terms, the outward crossing was uncomplicated. Barely out of sight of Spanish territory in the Canary Islands, his small flotilla picked up the north-easterly trades that carried it across the Atlantic in little over a month. In comparison, da Gama’s voyage lasted over two years, covering some 24,000 miles of ocean, a distance four times greater than Columbus had travelled. When Columbus sailed to America he had to chivvy his men through thirty-three days without sight of land; da Gama’s crew endured ninety. Their voyage was, in every sense, an epic – literally so, inasmuch as it provided the inspiration and subject matter for Portugal’s national poem, the magnificent, sprawling Lusiads of Luís Vaz de Camões, its 1,102 stanzas an appropriately monumental and meandering tribute.

As tends to be the way with epics, the drama was supplied by a combination of heroism, foolishness and cruelty. After saying their last prayers in the chapel of Lisbon’s Torre do Bélem, the crew bade farewell to wives and families before setting out on their ‘doubtful way’ (caminho duvidoso), directing their three small caravels and one supply vessel down the Tagus on 8 July 1497. Passing the Canaries, they headed south down the African coast, skirting the western bulge of the continent towards the Cape Verde islands. Next they turned their prows south and west into the open ocean, hoping thereby to avoid the calms of the Gulf of Guinea – so much they already knew from the many earlier Portuguese expeditions that had sought African gold and slaves for decades. Dropping below the equator they passed from a northern summer into a southern winter whose gales, now deep in the southern latitudes, slung them back east to Africa. Even now they were still far to the north of the Cape of Good Hope, and they had to fight a tortuous battle against adverse currents and winds before they could finally round the bottom of the continent. When they finally left the Atlantic for the Indian Ocean they were already six months from home.

Thus far their course had been scouted by the exploratory voyage of Bartolomeu Diaz a decade earlier; now they were entering uncharted waters. With scurvy starting to get a grip on his exhausted crew, da Gama cautiously worked his way north along Africa’s east coast in an atmosphere of steadily mounting tension. Stopping for supplies and intelligence at various ports along the way, the Portuguese met with mixed receptions, ranging from wary cooperation to bewilderment and outright hostility. A lucky break came at the port of Malindi, in present-day Kenya, where they had the immense good fortune to pick up an Arab pilot familiar with the crossing of the Indian Ocean. By now it was April, and the first gatherings of the summer monsoon, blowing wet and blustery out of the south-west, propelled them across the ocean in a mere twenty-three days. On 17 May, ten months after leaving Portugal, a lookout smelled vegetation on the sea air. The following day, through steam and sheets of scudding monsoon rain, the mountains of the Indian hinterland at last rose into view. They had reached Malabar, India’s Spice Coast.

Thanks to good fortune and the skill of their pilot they were no more than a day’s sailing from Calicut, the principal port of the coast. Though they naturally had little idea of what to expect, the newcomers were not wholly unprepared. With their long experience of voyages down the west coast of Africa, the Portuguese were accustomed to dealing with unfamiliar places and peoples. On this as on earlier voyages, they followed the unsavoury but prudent custom of bringing along an individual known as a degredado, generally a felon or outcast such as a converted Jew, whose role it was to be sent ashore to handle the first contacts with the local population. In the not unlikely event of a hostile reception the degredado was considered expendable. And so, while the rest of the crew remained safely on board, on 21 May an anonymous criminal from the Algarve was put ashore to take his chances.

A crowd rapidly formed around the exotic, pale-faced stranger. To the bemused Indians little was clear, other than that he was not Chinese or Malay, regular visitors in Calicut’s cosmopolitan marketplace. The most reasonable assumption was that he came from somewhere in the Islamic world, though he showed no signs of comprehending the few words of Arabic addressed to him. For want of a better option he was escorted to the house of two resident Tunisian merchants who were, naturally enough, stunned to see a European march through the door. Fortunately, the Tunisians spoke basic Genoese and Castilian, so some rudimentary communication was possible. A famous dialogue ensued:

Tunisian: ‘What the devil brought you here?’

Degredado: ‘We came in search of Christians and spices.’

The answer would not have pleased the Tunisians, but as summaries go this was an admirably succinct account of the expedition’s aims.

Spices figured no less prominently in da Gama’s motivation than they had in Columbus’s voyage five years earlier. The Christians too were more than a matter of lip service; to some extent commercial and religious interests went together. Yet of the two the spices offered richer pickings, and there could be little doubt which mattered more in the minds of the crew and those who came after them. The anonymous narrator who has left the sole surviving account of the voyage goes straight to the heart of the matter:

In the year 1497, King Manuel, the first of that name in Portugal, sent four ships out, which left on a quest for spices, captained by Vasco da Gama, his brother Paulo da Gama and Nicolau Coelho. We left Restelo on Saturday, 8 July 1497, for a voyage which we hope God allows to end in his service. Amen.

Their prayers were not in vain. Whereas Columbus was an entire hemisphere off track, the Portuguese had hit the motherlode.

When da Gama’s degredado splashed dazedly ashore in May 1498, the Malabar coast was the epicentre of the global spice trade; to some extent, it still is. Located in the extreme south-west of the subcontinent, Malabar takes its name from the mountains that sailors see long before the shore comes into view, a suitably international hybrid of a Dravidian head (mala, ‘hill’) grafted onto an Arabic suffix (barr, ‘continent’), the latter supplied by the Arab traders who dominated the westward trade from ancient times through to the end of the Middle Ages. The mountains are the Western Ghats, whose bluffs and escarpments form the western limit of the Deccan plateau. The coast, a low-lying, fish-shaped band of land squeezed between sea and mountains, was, and is, a centre of both spice production and distribution. Calicut was the largest but not the only entrepôt of the coast. A string of lesser ports received fine spices from further east for resale and reshipment west, onward across the Indian Ocean to Arabia and Europe. From the jungles of the Ghats merchants brought ginger, cardamom and a local variety of cinnamon down from the hills, punting their goods through the rivers and backwaters that maze across the plain to the sea. Above all, they brought pepper.

Pepper was the cornerstone of Malabar’s prosperity: what the Persian Gulf today is to oil, Malabar was to pepper, with similarly mixed blessings for the region and its residents. The plant that bears the spice, Piper nigrum, is native to the jungles that cloak the lower slopes of the Ghats, a climbing vine that thrives in the dappled light, shade, heat and wet of the tropical undergrowth. Though it has long since been transplanted around much of the tropical world, connoisseurs of the spice claim that Malabar still produces the finest. Like practically every other aspect of life in Malabar, pepper’s cycle of harvest and trade moves to the seasonal rhythms of the monsoon (the word derives from the Arabic mawsim, ‘season’). In late May or early June the rains sweep in on a front of gusty south-westerlies from the Arabian Sea: the ‘burst’. Over the next few months the first blooms appear on the pepper vines as the upper slopes of the Ghats are drenched in a daily Wagnerian deluge of inky clouds and crashing thunderstorms. By September, the rain falls less heavily, and the clouds and mists boil away up the valleys and gorges. A long, sultry heat descends on the hills. In November, the winds flip 180 degrees, blowing mild and dry out of the north-east as the hot air of the central Asian summer is sucked southward, down the subcontinent from the Himalayas, across the Indian plain to the ocean. In this hot, dry atmosphere the pepper berries cluster and swell; their pungent, biting flavour ripens and deepens. By December they are ready for harvest. Walk any distance in rural Malabar before the return of the monsoon and you are likely to have to make a detour to avoid a patch of peppercorns left out to dry in any space available.

Thanks to the combination of spice and monsoon, when Malabar first emerges into history the coast was already a crossroads frequented by traders and travellers from around the Indian Ocean world. The spices were the end, the monsoon winds the means. There were communities of Chinese and Jews here from the early centuries AD, the latter constituting one of the oldest Jewish communities outside the Middle East. Long before then there had been visitors from Mesopotamia: pieces of teak – another attraction of the coast – were found by the archaeologist Leonard Wooley at Ur of the Chaldees, dating from around 600 BC.* By the time of Christ, when da Gama’s native Portugal was a bleak and barren wilderness of Lusitanian tribesmen peering out on the sailless waters of the Atlantic, Greek mariners were arriving in Malabar in such numbers that one recherché Sanskrit name for pepper was yavanesta, ‘the passion of the Greeks’. Thanks largely to its vegetable wealth Islam was established here from the seventh century onward; Indian Muslims thriving, settling and converting over half a millennium before their Moghul co-religionists stormed down from central Asia. Even in da Gama’s day there were a handful of intrepid Italian merchants who had arrived by the long and dangerous overland route from the Levant. When da Gama dropped anchor Malabar was the most important link in a vast and vastly profitable network, and had been so for centuries.

For those who profited thereby da Gama’s arrival represented an almighty spanner in the works; for the Portuguese, a coup de théâtre. Now for the encore. Surviving the voyage out was one thing, but the Portuguese had still to find their way through the perilous shoals of Malabar politics, in which respect they were utterly in the dark. It seems that da Gama had expected to find in India a situation similar to that the Portuguese knew from their trading voyages to West Africa, where they could barter trinkets of low value for stellar returns, and so was taken aback to find the rich and sophisticated Indians demanding payment in gold and silver. As with Columbus’s experience in the Americas, his misconceptions had tragicomic results. On his march into Calicut to meet its ruler, the Zamorin, da Gama was so overwhelmed by the proliferation of peoples and religions, and so confident of finding the eastern Christian lands of Prester John, that he mistook a Hindu image of Devaki nursing Krishna for a more familiar mother-and-son pairing. Though puzzled by the teeth and horns on some of the statues of the ‘saints’, he promptly fell to his knees and thanked the Hindu gods for his safe arrival.

This was, however, an isolated and definitely unwitting display of religious tolerance. With da Gama regarding himself as every inch the righteous crusader, and out to garner profits no matter the means, Indo-Portuguese relations were practically bound to get off to a rocky start. In his first meeting with the Zamorin, da Gama promptly set about aggravating an already fraught situation with a mixture of religious bigotry and peevish ignorance. The truculent tone of the new arrival might have been calculated to cause offence. The Zamorin was a civilised and sophisticated ruler used to receiving traders from around the Indian Ocean world and one, moreover, most definitely unused to the tepid tribute and paltry gifts – honey, hats, scarlet hoods and washbasins – offered by the Portuguese. Who were these uncouth newcomers that they should treat him, the Lord of Hills and Waves, like some naked barbarian chieftain?

On all sides there was confusion, misunderstanding and suspicion. Da Gama was briefly detained ashore, further fuelling his already ripe paranoia over the ‘dog-like’ behaviour (perraria) of the Indians. On board the Portuguese vessels there was a steadily mounting nervousness that the Moors had poisoned the Zamorin’s mind. These fears were justified, if self-fulfilling: it was after all only rational for the Moors, sensing an opportunity to nip this new threat in the bud, to have encouraged the Zamorin to imprison or indeed execute the ungracious newcomer.

The Zamorin, however, hedged his bets. He granted da Gama’s men freedom to trade, and through the months of July and August they carried on a desultory exchange in an atmosphere of mutual recrimination and distrust. After a summer of escalating tension, da Gama sailed for Portugal in bad odour, leaving a mood of foreboding behind. As he raised anchor, he angrily threatened a group of Moorish merchants, warning them that he would soon be back. He had every reason to be as good as his word, for he left with the fruit of the summer’s efforts, a respectable cargo of spice.

Unlike Columbus’s altogether less convincing souvenirs from the Indies, there was no doubting da Gama’s evidence. But spices aside, exactly what else he had found would not be perceived for several years. In his report to the king, da Gama painted a somewhat distorted picture. Even now he was convinced that Hinduism was a heretical form of Christianity. After two months in the country, he seems to have concluded that the unmistakable polytheism he had seen was some sort of misconceived Trinity. But what was clear to all was the prospect of great things to come, and King Manuel was not one to shirk such a golden opportunity. The doubters’ faction at court and the voices of caution had been silenced. The way to India and its riches lay open. Preparations were immediately put in place for a second, larger fleet.

It sailed on 8 March 1500 under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral, his thirteen ships and more than a thousand-strong crew dwarfing da Gama’s scouting trip of three years earlier. If da Gama’s mandate was reconnaissance, Cabral’s was empire-building. Once in India some of the uncertainties and anxieties of the first voyage soon crystallised into ruthless imperial intentions. (En route to India Cabral discovered Brazil – another unforeseen consequence of the search for the Indies.) Arab and Gujarati traders, Jews and Armenians already established in the trade – all were infidels, ergo enemies. Contrary to a long-cherished notion of liberal and nationalist Indian historians, the Portuguese were not the first to bring violence to the ocean, but they certainly did so with unprecedented expertise. They were moreover the first to claim ownership over more than a localised corner of its waters, and to do so in the name of God. When Camões versified his countrymen’s feats he had Jupiter, in a Virgilian touch, dispense imperium to the conquering Portuguese: ‘From the conquered riches of the Golden Chersonese, to distant China and the farthest islands of the East, the whole expanse of the ocean shall be subject to them.’ And this, substituting ‘God’ for ‘Jupiter’, was exactly how King Manuel saw matters. On the king’s orders, Cabral was to seize control of the spice trade by any means necessary. Portugal’s work was God’s work.

For a time, it looked as if God was indeed on their side. Da Gama had made the gratifying discovery that Arab traders had no answer to the fearsome naval artillery of the Portuguese. Now it fell to Cabral to flex his muscles. On his arrival in Calicut he demanded that the Zamorin expel all Muslim merchants, which naturally the Zamorin refused to do. Calicut’s prosperity, after all, was built on the twin pillars of free trade and respect for foreign shipping. Relations went from bad to worse. As the Zamorin stalled, Cabral seized a large and heavily laden Arab ship preparing to sail for the Red Sea, provoking a riot in which fifty-three Portuguese trapped onshore were killed. In response, Cabral turned his artillery on the city. The savage two-day bombardment forced the Zamorin to flee for his life. Having had the temerity to resist the Portuguese diktat, Calicut and all within were now fair game. The Portuguese seized or sank all Muslim shipping they could lay their hands on; Muslim merchants were hanged from the rigging and burned alive in view of their families ashore.

Calicut’s fate was just a taste of things to come. In the years that followed, similar treatment was revisited on the city and on other Malabar ports, often provoked by local squabbles but all to the strategic end of establishing a royal monopoly over trade in the Indian Ocean. Henceforth traders of all nations would require a permit to sail waters they had sailed freely for centuries. The goal was nothing less than to make the Indian Ocean a Portuguese lake. All competition would be taxed or blown out of the water.

And so, in their clumsy, bloody way, Portugal’s pioneers in the East set about building an Asian empire. It would last, in parts, for nearly five hundred years, the first of all European empires in Asia, and the longest-lived. Unlike its successors, however, this new empire was not based on the occupation of territory, the filling-in of the blank spaces on the map, so much as it was aimed at the acquisition of a network of trading stations and forts. The empire would rapidly diversify, but it is fair to say that spice provided the early impetus. What mattered was control over the centres of trade, above all the spice trade. In its formative years Portugal’s Estado da India was, as one historian has dubbed it, the pepper empire.

It was certainly spice that impressed Lisbon and its rivals. Looking back on the golden epoch of the conquests from an age of imperial retreat, the Jesuit historian Fernão de Queyroz (1617–1688) claimed that da Gama’s legacy and ownership of the spices in particular could not fail ‘to astound the world’. In Europe, it was the Italians who were most astounded, for it was they who stood to lose the most. By the time Asian spices arrived in Mediterranean waters the trade was effectively monopolised by a handful of big Venetian merchants, for whom da Gama’s démarche opened a terrifying prospect. Incredulity and caution on the first reception of the news of da Gama’s voyage turned to dismay when news came of a second and then a third expedition. In 1501 two Portuguese ships laden with spices arrived in Flanders and immediately set about undercutting the Italians who had long dominated the market. Venetian merchants in Alexandria and the Levantine ports and marketplaces soon found prices soaring, and for a few years the spice galleys returned empty. La Serenissima trembled. There was scant consolation in the sneering nickname conferred on Portugal’s King Manuel, the upstart ‘grocer king’.

This Manuel knew full well. In letters to various crowned heads of Europe, penned within days of da Gama’s return, King Manuel crowed his success, styling himself ‘Lord of Guinea, and of the Conquest, the Navigation and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India’, and boasting of the vast profits that would now flow through his kingdom – and away from Venice. Among the recipients of these letters were the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, his parents-in-law; given the poor returns of their own investments in spices they must have found it particularly galling to learn of Manuel’s successes among the glittering riches of the glorious East, at a time when Spain’s explorers were still scraping around a scattering of heathenish Caribbean islands. This Manuel fully appreciated, so for good measure he had his letters printed into pamphlets for public consumption. One particularly gloating missive invited the Venetians to come and buy their spices at Lisbon, and indeed, in the desperate year of 1515, they had no alternative.

For a time it looked as though events in far-off Malabar had sparked a revolution in the old Mediterranean order. During the summer of da Gama’s return the Florentine Guido di Detti gloated that the Venetians, once deprived of the commerce of the Levant, ‘will have to go back to fishing’. The Venetians feared as much themselves. In July 1501 the Venetian diarist Girolami Priuli estimated that the Portuguese would make a hundred from every ducat they invested; and there was no doubt that Hungarians, Flemish and French, Germans and ‘those beyond the mountains’, formerly wont to come to Venice for spice, would now head for Lisbon. With this gloomy prognosis in mind he predicted that the loss of the spice trade would be as calamitous ‘as the loss of milk to a new-born babe … The worst news the Venetian Republic could ever have had, excepting only the loss of our freedom.’

For all those who envied Venice its riches it was an appealing prospect, but they were to be disappointed. As far as business was concerned, the Venetians were no babes in arms. In the longer run, Portugal’s grasp of the spice trade proved more shaky than it had at first appeared. Historians long accepted Manuel’s boasting at face value, taking it for granted that da Gama’s voyage succeeded in neatly redirecting the spice trade from the Indian into the Atlantic Ocean, but this was far from being the case. After a few disrupted decades, as the shock of early Portuguese conquests reverberated back down the spice routes, Alexandria and Venice staged a comeback. In the 1560s there were so many spices for sale at Alexandria that a Portuguese spy suggested Portugal should abandon the Cape route altogether and ship its spices via the Levant in order to cut costs. So great was the flow of illicit spices through the Portuguese blockade that there was speculation that the Portuguese viceroy was in tacit revolt against the king.

That Portugal failed to monopolise the spice trade is not, in retrospect, so remarkable. Even with their fearsome cannons, the Portuguese effort to lord it over the Indian Ocean, so far from home, was an extraordinary act of hubris, and Manuel’s vainglorious titles little more than a fantasy. With their religious bigotry and cavalier attitude to established networks the Portuguese rapidly accumulated enemies who would in due course cost them dear. Though they were unable to face the Portuguese ships in a shooting match, smaller, swifter Arab vessels enjoyed remarkable success in avoiding the blockade and generally raising costs. For the Portuguese crown every fort, every cannon and every man under arms represented a loss of profits. Violence was bad for business. Beset by enemies on the outside, the Portuguese empire proved remarkably porous from within. Subject to strict rules, compelled to buy and sell at prices set by the crown, and facing the likely prospect of an early death from some foul disease, shipwreck or scurvy, the Portuguese in India, most of whom had gone east to enrich themselves, had few legal means of doing so. Endemic smuggling, corruption and graft were the inevitable result. There were too many temptations to plunder, and little to stop it. The costs of the pepper empire raced ahead of returns. For all the sound and the fury (and the poetry), this was a creaking, leaking empire – ‘There is much here to envy,’ as one of da Gama’s descendants summarised matters.

In May 1498, however, all such future complications were far from the minds of da Gama’s crew. There were more pressing matters to attend to. As they walked dumbfounded through the streets of Calicut, ogling the rich houses of the great merchants, the huge warehouses bursting with spice, the mile-wide palace and the rich traders passing on their silken palanquins, they naturally thought they had hit the big time. Their first priorities were getting rich quick, or simply making it home. Da Gama contrived to make this already daunting task infinitely more difficult by sailing too early, before the monsoon winds had shifted. The crossing to Africa, three weeks’ sailing on the outward leg, now took three months. Thirty crewmembers died of scurvy, leaving a mere seven or eight able-bodied mariners for each vessel. The third caravel was abandoned, ‘for it was an impossible thing to navigate three ships with as few people as we were’. By the time they finally returned to Lisbon, only fifty-five of the 170 or so who had set forth remained. Da Gama himself survived due to the hardiness of his constitution and, in all likelihood, the superior quality of the officers’ rations (the nutrients in the wine and spices reserved for officers may have made the difference). Among the casualties was his brother Paulo, who died in the Azores, only a few days’ sailing from home.

Even in purely financial terms, the initial results were less spectacular than had been hoped. The two ships that returned to Portugal were compact, designed for discovery, not cargo. As a result the expedition came back with a substantial but scarcely earth-shattering haul of spices. The survivors brought little more than curios, in some cases paid for, quite literally, by the shirts off their backs. But in the heady days of da Gama’s return, when the king himself hugged this once obscure nobleman and called him his ‘Almirante amigo’, any future problems were far from anyone’s mind. For if da Gama’s experience foreshadowed the extreme hazards of the sea route to the Indies, it also gave a stunning demonstration of its promise. As they offered prayers of thanks in Bélem, where they had knelt two years earlier, all the survivors had reason to hope that the spices da Gama brought back were harbingers of greater things to come. The financiers rubbed their hands; from Antwerp and Augsburg the great banking houses of Europe looked on remote little Portugal with new interest.

What was clear was that the old order had been rattled, and there was good reason to believe that it would shortly be turned on its head. A decade after da Gama’s arrival in India an itinerant Italian by the name of Ludovico Varthema travelled through the Portuguese Indies and beyond, witnessing in person the prodigious infancy of Europe’s first Asian empire. He spoke for many in 1506: ‘As far as I can conjecture by my peregrinations of the world … I think that the king of Portugal, if he continues as he has begun, is likely to be the richest king in the world.’ At the time, it seemed a reasonable surmise. Measured by the spicy mandates of their missions and in the assessment of the day, Columbus looked the failure, and da Gama the success.