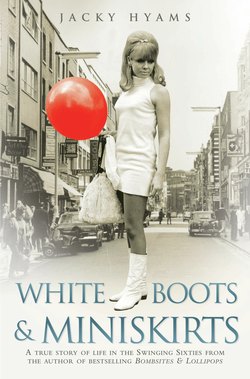

Читать книгу White Boots & Miniskirts - A True Story of Life in the Swinging Sixties - Jacky Hyams - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE COMPLAINTS MANAGER

ОглавлениеA light aircraft, a Piper Aztec, is taking off from a small airfield just outside London.

It’s a clear, bright summer weekend afternoon, a light breeze, little cloud, remarkably good flying conditions. As the plane climbs to 2,000 feet, anyone looking up from below might envy the passengers the delight of their winged freedom on this, a perfect day. If they continued to look up, they might have been somewhat impressed by the daring but perfectly executed aerobatic roll executed by the pilot a few minutes later.

Brilliant stuff. If you’re on the ground. But I’m up in the tiny plane, strapped in behind the pilot, Des, and his friend, Jeff. A gregarious, charismatic, speedy chatter-upper in his early thirties, Jeff is hell bent on making a real impression on me, a 21-year-old secretary working in his office. Well, it’s one way to pull the birds, eh? Persuade your best mate, a former RAF fighter pilot, to take you and your latest object of desire up in the clouds for a few aerobatic show-off manoeuvres.

‘Show Jacky some tricks, Jeffrey,’ laughs Des, as he manoeuvres the controls to send us into that head spinning, stomach-churning, 360-degree spin. Luckily, I’m not expecting this. No time to anticipate the sheer terror of being flipped upside down in a flimsy airborne tin can: it’s all over in a matter of seconds. I manage to remain impassive, stay outwardly remote, in my gingham mini-dress with the white organdie collar, cutaway shoulders and short white Courrèges boots, though it’s the fake cool of ignorant youth, rather than any kind of real courage or bravado, that gets me through this terrifying moment. This is the sort of thing that’s exciting once you’ve done it, I tell myself. He could’ve asked me first…

‘All right Miss Hyams?’ grins Jeff, turning back to give my exposed bare knee a quick caress. Jeff’s a Hackney lad, common ground with me that he’s exploiting to the hilt in his quest, so far thwarted, to get me into bed.

‘Yeah,’ I smile, remembering to show my girly gratitude to my host. ‘Er… nice one, Des.’

‘Next time we’ll show her some more tricks, eh Jeff?’ winks Des as he expertly handles the controls and guides the plane down towards the landing strip. Jeff looks chuffed: ‘tricks’ are his thing all right. I’m well used to the double entendre: it goes on all day, every day in the office. But I’m not the giggly, wriggly, ‘Oo, you are awful’ type. It’s usually a sarcastic retort, a sharp put down. Yet today, for some reason, I don’t bite back.

Still, for 1966, this is a pretty resourceful ploy for seduction. Getting young women up in small planes isn’t exactly commonplace. Nor is flying itself, still mostly for the comfortably off, though I’ve already had my first flight to Italy and, by the end of the decade, five million Brits will be off holidaying abroad, mainly on package-deal charter flights.

Mostly, men deploy their cars as girl bait, especially those who can afford to show off in flash Rovers, souped-up Minis, Triumph TR4s or MG MGBs. Young office girls are still some way off from buying their own cars after they pass the test, propelling themselves around town independently. And because it is still quite common for sons and daughters to live in the family home until marriage, car ownership means a guy has, at least, a love trap on wheels. Otherwise it’s outdoor sex (never a brilliant idea in Blighty’s climate, but nonetheless popular because it’s comparatively easy to find a secluded spot to carefully place the blanket) or the deserted office or shop floor – more popular then than you’d ever imagine. Or, as a final resort, there’s always the family home when unoccupied: not always achievable with other siblings hanging around.

Jeff hasn’t yet quite convinced me of his charms on this day of the aerobatic somersault. He’s an outrageous flirt around the electronics company where we both work and there’s an element of mystery around his existence that makes me initially wary (it will take several years before I learn to trust those first, crucial instincts).

He claims to live with a brother, somewhere in deepest Hertfordshire. The truth is he lives in sin in Pinner with a much older woman he’s been with for years. There’s also an illegitimate son and the boy’s mother, tucked away in Scotland, seen about once a year – a brief affair from Jeff’s national service days. Yet I don’t know about any of this when, a few months later, I willingly succumb to his persistent advances in the back of his Rover.

This relationship with Jeff, which continues until I learn the whole truth a couple of years later, brings my tally of boyfriends up to three. There’s Bryan, the on–off boyfriend, a racy, chubby advertising man I knew before leaving home in Dalston. I go to pubs, Indian or Chinese restaurants with Bryan and sleep with him, usually in his flat, albeit intermittently. And recently, I’ve regularly started to see Martin, a less dashing figure than the other two – a wiry, ambitious shop manager from Islington, a sharp dresser, almost a Mod, whom I mostly see on weekends for drives and trips to the cinema.

It sounds odd now, but our favourite drive is to get into Martin’s much-prized Mini and drive to Heathrow airport (people actually drove to airports then just to look at the planes, a popular family day out). Today’s traffic-clogged, hellish and unloved route from central London to Heathrow, the A4, was very different then, virtually empty and car-free. Sometimes we whizz down from central London to the airport in 20 minutes or so. No unending stream of planes taking off every 60 seconds at Heathrow then. Park outside, go into the quiet terminal, blissfully free of innumerable shopping opportunities and sit there, watching the BEA Comets and the Spantax Coronados. Without the crowds and bustle we know today, it is all quite… romantic. ‘I’m gonna be on one of those BOAC planes one day, when I go to live in the States,’ Martin says confidently. And he does just that a few years later.

I never do get too involved with Martin for some reason, though I admire his sparky determination to move his life along and not just accept what he’s been dished out. Our dates never go beyond the odd snogging session in the Mini. Who knows? Maybe he had another girl, maybe he hid his shyness or lack of sexual experience under his sharp-suited exterior.

Yet had anyone asked me back then, I’d have told them it was perfectly acceptable for a young single woman to go out with – and sleep with – as many men as she pleased, get drunk if she felt like it and treat life like an adventure, a quest for experience, rather than a single-minded march towards marriage and motherhood. After all, it was 1966, wasn’t it? Sex was now freely available. Thanks to the arrival of the contraceptive pill, women of all ages, single or married, no longer had to worry about the threat of unwanted pregnancy or men who couldn’t abide johnnies. (‘Like picking your nose with a boxing glove,’ as one wag described it.)

The ’60s, of course, are historically defined by the sexual revolution because once the pill was introduced (1961) and the laws on abortion changed (1967), sex became quite a different proposition, as women had real choice in such matters for the first time ever. All this sex revolution stuff was sweet music to my ears. Yet it was still a matter of time before those changes actually took effect in everyday lives: the reality across the land was not quite the way I was choosing to see it. Women’s take up of the pill in the ’60s was tiny: only one in ten were actually taking it by the end of the decade. If my conversations with girlfriends were anything to go by at that point, I was a little bit different to those I knew in being quite so generous with my favours. Some of us were bravely, blindly, diving into the freedom of choice or ‘love is free if you want it’ idea. But not half as many were going for it as one might imagine from the burble and hype around the sexual revolution and swinging London in the mid-1960s.

Today no one bats an eyelid at single women juggling lovers of either sex, having one night stands at whim or even opting for what are known, somewhat bleakly, as ‘fuck buddies’. This kind of thing was not really happening for the majority in the mid-1960s. Essentially, the sexual freedom hype, as purveyed by the newspapers of the time (let’s face it, it’s an eye-catching story, particularly when there are pictures of beautiful young women in tiny skirts to go with it), created a somewhat confusing picture of a wild, free-love society which, to a greater extent, was still the very opposite: it remained solidly class-bound and reticent in all matters sexual. Youth was going mad, but for now the older generation was having none of it.

Nonetheless, the genie is well and truly out of the bottle. The influence of the maverick young leading the way, the Pied Pipers of the ’60s, is enormous: the Beatles, Stones, snappers David Bailey and Terence Donovan, models Jean Shrimpton, Celia Hammond and Twiggy, actors such as Michael Caine and Terry Stamp, and girls like Cathy McGowan, the Ready Steady Go presenter with her glossy long hair and dead straight fringe. Mostly (but not quite all) they are working class, yet they are positioned right at the heart of all the hype by dint of what they represent – youth, glamour, talent and beautiful role models for millions of youngsters.

Beyond the buzzy, happening centre of London – just a few square miles of tiny clubs, shops, an area running from posh, louche Chelsea, the King’s Road, the fabled, tiny Abingdon Road shop called Biba (which moves to Kensington High Street in 1965) and across to the West End and Soho – the swinging city runs out of steam. Out in the groovy live music venues in south-west London’s suburbs – the Bull’s Head at Barnes (jazz) or the Crawdaddy in the Station Hotel, Richmond (the bluesy launch pad for the Rolling Stones) – there had been a buzz going since the early ’60s. Yet way beyond, in the outer suburbs, the provincial cities or small towns, free love, long hair for men and dolly birds in micro minis are on their way – but have not yet arrived. Only by the time of the summer of love, 1967, the pivotal moment when the Beatles launched the groundbreaking Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and young people started piling in to cool, small, trendy venues in cities and towns like Canterbury, Bristol, Norwich, York and, of course, Liverpool, was the effect of it all to move right across the country, fuelled by the massive influence of the music and those making it – and of the powerful American hippie culture.

Yet at this point, real economic freedom, as we know it now, is still a long way away for ordinary, working class girls like me. Career options for professional women remain limited, even for the university-educated middle classes. Beyond shop, factory or office and secretarial work there is – what? Nursing, teaching and the civil service, of course. And for the educated women, academia. A few middle-class women venture into creative fields like advertising or journalism, yet the limitations don’t lift in the ’60s. Girls’ jobs remain more or less what you do before finding a man to marry, rather than the sometimes overblown career expectations of millions of young girls now, spurred on by fantastic dreams of instant stardom and lifelong riches.

I may be more rebellious in my thinking than the other girls I know of my age, some of whom are already married. In my case, however, I am a child of my times in that I am heavily influenced by the imagery and the printed word. Like so many others, I soak it all up. Because I have avoided further education and dived into the working world at 16, most of my ideas about life and sex come through devouring magazines like three-month-old US Cosmopolitans, eagerly purchased from Soho newsagents each month. (Britain’s Cosmo does not arrive until 1972.)

US Cosmo, with its bold editor, Helen Gurley Brown (best quote: ‘Bad girls go everywhere’), pushes forward the daring new belief that women can enjoy sex, pick and choose their partners – they don’t have to focus solely on marriage and motherhood to lead a fulfilled life. They can make themselves gorgeous – and follow their own career path. This, to me, makes perfect sense. All of it. I already understand, by pure instinct, that the traditional path up the aisle isn’t going to suit me. Too restrictive, too mundane. Men? Yes, please. Sex? Ooh, yes. Marriage? Er… no thanks. Babies? Pass. Though it will be many years before the notion of career ambition starts to emerge for me.

Yet for all my defiance and media-led ideas about sexual freedom, I am still stuck with one thing: the men around me continue to retain all the power. Even at this mid-1960s point when the social change really begins to accelerate, the men are still setting the agenda of the chase. You can reject an offer, an advance, a date. But if you like someone, fancy them, you still have to sit around waiting for the phone to ring, summoning you. It’s a convention I profoundly resent, partly because I am terminally impatient but also because I see all this waiting as grossly unfair. My argument is: if you can phone me when you want, why can’t I phone you? Yet because such equality doesn’t yet exist and communication itself is so limited by today’s standards – phone, letter or a knock on the door – I’m still stuck with that wait, staring at the black Bakelite instrument, willing it to send out its shrill, exciting sound.

This limited communication also gives men the edge in terms of keeping you in the dark about what they are actually up to. It’s so much easier for them to be vague or non-committal. Or simply untruthful, which some ’60s men are if they’re juggling two ‘birds’ at a time. Unless they live or work near you, know your friends and family, how can you, living in the heart of the big city, know anything about what they’re really doing? No Facebook, Google or website to check someone out. No blog, no exchange of text messages or tweets, mobile phone lists. No email to whizz off a swift one-line retort or naughty come-on. Telegrams, delivered to your front door, usually by bike, are the only other means of fast communication. You can hardly send a telegram to a man: ‘HURRY UP AND RING ME, YOU BASTARD’. Or even: ‘WHAT’S GOING ON, IT’S BEEN TWO WEEKS SINCE YOU CALLED’.

Voicing these things out loud when the call does come never seems to get you anywhere. Just more waffle, excuses and vague references to ‘work’. If a man you’re entangled with says they’re going ‘up north on business’ (a popular favourite in London, the frozen north being a remote place to be approached with considerable caution) for an unspecified period, you accept it. People simply could not go round checking up on each other’s behaviour the way they do now. So ’60s men, for all the historical hype about the era, got away with a lot that would be very difficult for them to get away with now. Unless you’re going steady or engaged, the unspoken rule is: they call, you can’t ring them.

Financially, too, they call the shots. Going Dutch or sharing the bill does not exist in traditional dating. The man pays for the drinks, the cinema seat, the meal, you drive there in his car – whatever needs to be paid for in cold cash is down to him. He’s doing the courting (unless he’s seriously mean, when it’s just a drive and maybe one or two drinks, if you’re lucky, in a local pub). The tradition of the man paying is reinforced by the fact that women earn much less than men and will continue to do so for a long time. Even in the rarer instances where there is some kind of equality of pay at work, you’re unlikely to find anything other than misogyny from the men in charge. ‘Equal pay, equal work, carry your own fucking typewriter’ was the mantra of one friend’s boss, an editor of a local newspaper when she joined the team as a youthful reporter.

You can, of course, invite a man round for a meal if you’re not living at home – the idea of the ‘dinner party’ is already starting to take hold now that growing affluence and full employment are virtually taken for granted – but for me this is hardly a thank-you or even an invitation to seduction. It’s more a way of expanding social horizons.

By now, I’m sharing a big flat in north-west London with three other girls where the rules of engagement with men are perpetuated. Our landlord had sensibly installed a coin-operated payphone inside the flat. After work it’s permanently engaged (without even any ‘call waiting’ to get someone off the line). All a smitten girl has for comfort is the unimpeachable, unbreakable parting male shot: ‘I’ll call you.’ Essentially, you are always waiting: at the dance (by now a club or disco) you wait for them to approach you. Then once they’ve escorted you home or you’ve been out with them – and decide you like them – you wait for the call. I’ve grown up with this, of course, but in my early twenties I still can’t quite accept it. Yet all this stratified behavioural code, had I only known it, was about to be turned upside down in less than a decade. More honest, open exchanges between the sexes were on their way.

The one thing the 20-something ’60s office girls have as their defence is their spending power on the latest fashionable gear. Traditional West End department stores like Swan and Edgar, Dickins & Jones and the new, fashionable chains like Neatawear go all out to tempt the young working spender with the very latest styles and fashions at prices aimed craftily at weekly pay packets. Temp secretaries, in particular, earn big sums working for an employment agency, moving around from office to office, if they’re prepared to put up with the hassle of switching around to strange faces and bosses every few weeks. Many dislike this idea, even with the lure of more money.

I earn around £12 a week. I manage to supplement that for the year or so when I work at the electronics company by handing out good leads that have come direct to me, the sales manager’s secretary, to a few select salesmen, getting £30 per sale in return. So I have plenty of cash to splash out on clothes, makeup and shoes. In fact, I blow the lot on clothes nearly every Friday when I receive my £9 (after deductions) pay packet, in exchange for my favourite styles: five guinea crepe dresses by Radley with wide trumpet sleeves or slinky, short, body-skimming shift dresses to go with tight, elasticated, white high boots from Dolcis, (£3 9 shillings and 11 pence) or killer pointy stilettos also costing a few pounds. What more does a girl need to get out there and attract?

Once the accounts girl has handed you the little brown envelope with the printed slip inside – no cash machines then or automatic salary transfers into a bank account, though 1966 saw the launch of the plastic revolution with the Barclaycard, the first credit card – away we all went at lunchtime, click-clicking down Oxford or Regent Street to a tiny Wallis (long relocated from its original home next to Oxford Circus tube, and still a popular chain to this day) or the bigger, pricier Fifth Avenue (long gone) on Regent Street or into one of the new boutiques for women popping up all around the hub of men’s trendy gear shopping: Carnaby Street.

There are ’60s labels I lust after like Tuffin and Foale (as spotted on Cathy McGowan on Ready Steady Go) and Cacharel from Paris. But they remain out of my price range, alas. Lured by the newspaper and Honey magazine hype, I venture to the famous Biba in its early days in Abingdon Road, off Kensington High Street one weekend. But the clothes in the packed little shop are far too tiny, cut too narrowly, too tight-sleeved and aimed at very lean King’s Road girls. The smocks and the dyed skinny vests are for the flat-chested, not for me.

Yet once I do find what suits me elsewhere, a swift wriggle into the new ultra-short op-art dress, zip it up, add a pair of pale tights, low-cut patent shoes and lo! Instant transformation into the siren I hoped to be, complete with super-thick false eyelashes or carefully painted-on lower lashes, (thanks, Twiggy) pink Max Factor lipstick, and a blonde, shoulder-length flick-up hairdo. And, of course, a small, quilted Chanel-style bag on a gold chain slung over the shoulder. The ’60s look.

Of course, we can’t all look like the high priestesses of classic mini-skirted ’60s blonde. Women such as Patti Boyd, Julie Christie, Catherine Deneuve or Bardot (my secret role models – talk about aiming high. In this at least I have real ambition). I’m not lean enough to be a classic dolly bird, though the slinky, short, patterned dresses in man-made slippery fabrics suit my curvy shape. With an unruly, curly brown mop I am very far from the requisite natural blonde with straight, shiny hair. Somehow, I’ve managed to transform myself into a yellowish peroxide blonde, often with nasty dark roots. But the fashions of the time help: bad hair days can be disguised because all kinds of head gear and caps have become ultra-fashionable, especially the plastic pillbox hat, worn on the back of the head revealing only a dead straight fringe. Consider Mandy Rice Davies wearing such a hat outside the court in 1963 at the height of the Profumo affair. The hat covers a multitude of sins, if you’ll forgive the pun.

Look carefully at those ’60s photos of the commuters streaming down Waterloo Bridge to work or thronging Oxford Street or Piccadilly. You can’t see too many overweight people, can you? My colleagues and girlfriends are different shapes and sizes – yet hardly any are what could be described as glaringly obese. The post-war generation, reared on free milk and NHS sticky orange juice as toddlers, remain quite lean by today’s standards. Yet by today’s standards, we eat badly – our office girl lunches, purchased with luncheon vouchers, now obligatory for any employer wishing to attract office staff, consist of cheese or ham crispy white rolls, Smith’s crisps, Kit Kats, Lyon’s Maid choc-ices or the somewhat dubious three-course café lunches for 2 shillings and 6 pence (watery tinned soup, something vaguely resembling meat and chips, treacle pudding and sticky yellow custard). All this, of course, is way too starchy and fat-laden. We are mostly ignorant about what really constitutes a sensible, healthy diet.

I’ve been diving into adventurous foreign eating territory in Soho, with cheap Chinese dishes like sweet’n’sour pork around Chinatown and Shaftesbury Avenue, since my late teens. Or sampling poppadums and curried chicken in north London Indian restaurants on my nights out with Bryan. But young women probably stay slim-ish because there aren’t many fast food outlets around yet. Small workers’ cafés, run by cheerful, hard-working Italian immigrant families, are the norm at lunchtime in the West End or the City, alongside the fast-growing rash of Wimpy Bars and Golden Egg chains spreading everywhere. These would eventually destroy places such as Lyons Corner Houses, so beloved of our parents’ generation yet losing popularity all the time until their demise in the early 1970s. Pub food? This barely existed beyond the odd sandwich, scotch egg or ham roll. White bread only. (‘Don’t say brown, say Hovis’ ran the 1950s ads for wheatgerm bread, but most pub managers continued to ignore anything but soggy sliced white bread well into the 1970s – and beyond).

In flesh-revealing terms, slimmer ’60s women were pretty modest by today’s standards. The mini is rampant, certainly, a revolutionary expression of new freedoms. There is a lot of leg and thigh on display. But you’re unlikely to see a seven-month pregnant woman at a bus stop in a clingy outfit emphasising the bump. Modesty, even with the mini around, would not vanish overnight.

Parents are mostly horrified and somewhat puzzled at the exuberant rise of the show-all mini. ‘You can’t go out like that’ becomes the mantra of a generation of women accustomed to ‘making do’ and rationing, using a black crayon to draw a fake ‘seam’ down the backs of their legs in wartime, nylon stockings having been virtually unavailable for many years. Now, those prized, precious, seamed nylons and suspender belts are on the way out too, replaced by the shiny white tights. Or, later, striped high socks with square-toed patent flats. It’s truly daft to attempt to combine a mini with stockings and suspenders, though there’s always the odd aberration, much to the delight of all the men in the office.

In a way, central London is my playground. I’ve grown up in a tough, streetwise area around Ridley Road market, but since my teens I’ve been spending most of my time working and going out in the West End, with occasional brief forays to fashionable Chelsea and Kensington. So the fashion influences are all around me, in my face, the shops a daily temptation. As a secretary I can job hop with remarkable impunity, mainly because there are so many office jobs on offer – and I am very easily bored. Offices big and small are taking on huge numbers of young school leavers and 20-somethings. With a bit of secretarial experience behind you, you can pick and choose, swapping around as often as you like.

For someone like me, with a restless, impatient nature, I am truly fortunate in that I hit the working world at just the right time: jobs a-go-go. Though with the carelessness of youth, I simply take this kind of freedom for granted. Gratitude for being given a job? Excuse me? Isn’t it the other way round?

What I really hanker for, but never acknowledge, is some sort of challenge or stimulus in my daily trek to the typewriter. The day-to-day routine, waiting for men to dictate to you so you can type, spells stultifying boredom to me, only enlivened by banter and cheeky retorts to colleagues around the office and the contemplation of the after-work drink or that night’s diversion. Yet such is the laissez faire of the employers, the ease with which office jobs are dished out, often with a minimum of formality (a CV was unknown, though a typed ‘reference’ from a previous job might be required by a diligent employer), I do manage to find the occasional minor challenge, simply because I opt to move around the job market frequently.

Far from being a model employee, the somewhat defiant, ‘couldn’t give a stuff’ attitude I’d deployed at school has now morphed into a kind of sneery arrogance about it all. I’ll do the work, rattle through it, no problem. I prefer to be doing, rather than just sitting around – something many bosses, who are quite happy to let you sit there twiddling your thumbs for much of the time, don’t quite comprehend. But the whole package, the office location, the general environment, the ambience of the place has to suit me. Otherwise I’m off.

My attitude is best illustrated by a job I held for a while after I’d quit the electronics company following a swift and unexpected management change – and the booting out of my boss. For about 18 months afterwards I worked in a job that was on the fringes of London’s ’60s fashion explosion. Though you’d never have guessed it if you turned up at the rundown building tucked away in the mews behind Oxford Street where the company had its headquarters. Scruffy is a polite word to describe the exterior. Dead rodents, rubbish, torn boxes and birdshit greet the visitor. Without any health and safety laws or human resources policies to keep things in check, small companies frequently operated in less than healthy environments. Yet this job, with all its drawbacks, remains one of the more diverting – and memorable – ways I found to make a living in the late 1960s.

Essentially, the job involved a bizarre corporate cover-up. I was hired as a sort of personal assistant to a director of a chain of shoe stores. No one ever bothered to explain to me beforehand that the job mostly involved pretending to be a man. A man who did not exist. OK, it didn’t go as far as me donning men’s clothes or doing impersonations. But essentially, for the time I worked in those dingy offices, I and I alone acted as a man of power and influence within the company, signing letters and documents bearing his name and often pretending to be a direct conduit to this non-existent individual. I have his ear. I am his official right hand, as far as the customers are concerned. His name: Mr Kirk-Watson.

To this day, I have no idea if this man ever existed. All attempts to grill my boss and other colleagues about The Real Kirk-Watson lead nowhere. No one ever actually knew him or anything about him. But in the minds of the shoe chain’s many customers, he is a significant presence indeed. And for the endlessly harassed store managers – the fast-expanding chain consists of about a dozen shops, all under consistent pressure to sell, sell, sell the fashionable shoes – he is their sole backup. Because Mr Kirk-Watson is effectively, a one-man customer service bureau, the person to whom all serious complaints about the shoes, mostly imported from Italy, are to be directed if the store manager cannot satisfy a complainant on the spot.

‘Madam, I’m sorry but I will have to refer you to Mr Kirk-Watson at head office,’ the manager would say ruefully, offering the often irate customer my office phone number before they stomped out of the store, muttering all sorts of threats involving the police, their family, the newspapers and so on. (TV consumer programmes such as the BBC’s Watchdog didn’t surface until the 1980s.) Consumer power – and legislation to protect the consumer – has not yet arrived.

Let me explain exactly why the customer frequently – and justifiably – loses the plot. The problem is that at a time when young, fashion-conscious customers with cash to spend are being courted like crazy, some retail outfits, focusing on turnover rather than quality or customer service, do not see themselves as being under any serious obligation to offer cash refunds if the goods are not up to scratch for some reason (and often they’re not, being produced in a mad rush to cash in quickly). Nor is there any widespread public knowledge showing, quite clearly, what the deal should be – what the retailer is legally obliged to offer the customer if the goods are undeniably faulty.

As for the shoes, usually at the cutting edge of fashion – stiletto heels with pointy toes, Chelsea or thigh-high boots, flat shoes with amazing trims – they are, as now, priced to tempt the weekly pay packets of the office girls and boys thronging Oxford Street and the surrounding shopping streets of central London. Yet these shoes are sometimes badly made. Heels fall off after one or two wearings. Sole and upper sometimes come apart within days. Trims or buckles just drop off.

The company import these shoes because they’re both ultra-fashionable and carry an extremely high profit mark-up. In Italy, still struggling to get its post-war export markets going, labour is much cheaper than here. So head office decree that the inconvenient issue of shoddy workmanship and angry customers is one for store managers to resolve, primarily to the advantage of the company. With the help of a man who does not exist. Looking back, I suspect that the use of a double-barrelled name was an attempt to impose some sort of intimidation on the lower orders. If so, they got it wrong because, by the late 1960s, cap-doffing and knowing thy place is on the wane – especially in the West End, the epicentre of all change. Though the quaint domestic service habit, where the servant employee uses the prefix ‘Mr’ before the boss’s first name (‘Mr Jack’) still prevails in this particular office.

In extremis, a credit note could be offered by the manager. Or even a replacement pair of shoes, if in stock. But shop managers, mostly, hold back from making these offers because credit notes affect their takings – and their commission. Head office policy ensures that they can hardly ever take any money out of the till and hand it back. The policy around complaints is to take the offending shoes back, offer to send them for repair and, if customers are still not happy with this, offer them Mr Kirk-Watson’s number to get them out of the store. A really furious or persistent phone call to Mr Kirk-Watson might – just – result in a credit note being issued direct from head office and not affecting shop takings. But a cash refund? Not on your nelly.

So the real Mr Kirk-Watson – a mini-skirted, mouthy, peroxide blonde with back-combed, lacquered flick ups and serious attitude to all comers – spends much of the working day fending off the stream of Kirk-Watson phone calls from angry or disgruntled customers. Now and again, the odd customer might venture into the premises to confront the elusive man, but once directed to the grungy ground-floor entrance at the back of the building, the only target for their ire is a lone receptionist, a tough blonde from the far end of the Metropolitan line called Babs. I am three floors up, safe in my tiny cubbyhole off my boss’s somewhat larger office. I never actually see a customer face to face.

My boss – Tom, the Oxbridge-educated son and heir to the booming business built up by his canny family in swift response to the ever-growing demand for fashionable gear for swingin’ Londoners – is rarely there. Nor does he ask much from me if he is around. Skinny, abrupt and often strangely distracted – it’s obvious that the demands of retailing are not really his thing, though I never discover what is – he is a timid sort of man, a weed really, in a crumpled three-piece suit that could easily have been slept in. It does not trouble me to take the endless stream of Kirk-Watson calls. The alternative is chatting to my friends on the phone or typing the odd bit of correspondence that, for some bizarre reason, Tom usually scribbles out for me in a disgusting scrawl – had he trained as a doctor? – on the back of old shoe boxes, a recycling habit he surely picked up from his mum during the war.

Tom’s fiancé, Helene – a French glamour puss – occasionally wafts into head office, reeking of Arpège and smothered in expensive Jean Muir or sporting ultra-fashionable short, pricey Jean Varon dresses (the designer’s real name was John Bates, the man who designed the clothes for the TV series The Avengers). Worldly and snobbish, she clearly overwhelms titchy Tom in every way. In her presence, he is a stuttering, gibbering wreck. An odd couple indeed. Tom has some strange habits. One involves light bulbs. When a new bulb goes in, he writes down the date. Then, when it pops, he carefully notes how long it lasted – a futile exercise as far as I could see, unless he planned to spend his life chasing Osram, the company making the bulbs. Letters are under careful surveillance too. If a letter misses the franking machine and needs a stamp, only second-class post may be used. And so on.

The Kirk-Watson scenario would at least prove to be good training for a future life as a journalist on the phone, talking to people who mostly don’t really want to talk to you – or alternatively, have a particular axe to grind. My phone routine is to politely present myself as K-W’s sidekick, explain that he’s away in Italy on a shoe-buying trip and offer to hear out their complaint. (If the customer has flatly refused to have the offending shoes sent off for repair, they are sometimes sent round to head office by the store manager, who phones me in advance to warn of an impending super-stroppy caller.) I have one available option (which rarely works) and politely offer to have the shoes sent off to the official body governing Britain’s shoe trade if the customer is willing to wait for a third-party decision on their complaint. This they mostly reject. So as a final resort, in what is clearly a hopeless case, I am empowered to offer a credit note – but usually after consultation with Tom and/or a manager.

Tom never argues or queries it when I put a credit note request in front of him. He lets me authorise and sign them, as Mr Kirk-Watson, in his frequent absences. With my East End background, acutely aware of fiddle potential, I could have expanded my personal shoe wardrobe considerably this way. Yet I don’t give in to this particular temptation, not because of any inherent scruple, but because it seems too easy to bother with and anyway, I get a good staff discount. As for Tom, he just wants a quiet life. After all, I’m taking the crap from a daily stream of angry customers who are mostly justified in thinking they’re getting a rotten, totally unfair deal. The shoe trade body do their bit, examining the shoes sent to them, explaining what has gone wrong in a polite letter, offering the customer a repair plus further advice on looking after their shoes. But of course, most customers don’t want this somewhat protracted deal, which takes weeks. They want their hard-earned cash back. Now.

And so I get used to people yelling at me, threatening to expose my company’s underhand ways, calling me a variety of unpleasant names because they can’t get their money back. Mostly I can’t reason with them (there is, of course, no training whatsoever for my customer service role, no direction on how to handle the unhappy customer), so I devise a neat trick. If the yelling and abuse goes on – and sometimes it continues for a few minutes, which is a real time-waster – I simply get on with my work, type my letters, carefully placing the phone beside me in the top drawer of my desk. That way I let the yelling, screaming customer give vent to their feelings without the irresistible temptation of answering them back or telling them to ’eff off. It gets a tad repetitive being told for the umpteenth time what a bitch I am, that my boss is a criminal, my employers thieves who deserve a good thumping. I discover a distinct pattern to their abuse. For once they’ve exhausted their vocabulary, run out of epithets, they frequently stop – and just slam the phone down in disgust.

So there I sit, a one-woman call centre with a timid boss and a rather odd game of passing the buck. It’s the lively, hyped-up shop managers, mostly, who keep me in stitches when we phone each other about the worst of it: the husband who pleads with us to refund the money because he’s so terrified of his wife’s vitriol, the screaming mum whose teenage daughter is in floods of tears because she wanted to wear the new stilettos on Saturday night, the posh woman who believes it’s her right to order ‘you shop people’ around and who claims all sorts of political connections with Churchill’s family to get her £10 back.

So there they all are, frustrated consumers in a world where there are no other means of redress other than firing their verbal bullets down a big black Bakelite phone on an unsteady wooden desk. And a 20-something girl in a thigh-high dress who doesn’t give a toss, feet up on the desk, as the frustrated customer screams themselves hoarse. Into an empty drawer.