Читать книгу A Bundle of Trouble - Jacqueline Dembar Greene - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4 The Girl in the Park

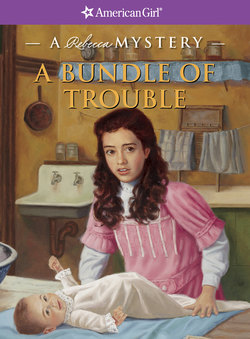

ОглавлениеBack inside the Rubins’ apartment, baby Nora began fussing more loudly than ever. Rebecca shook the tin rattle while Mama dabbed ointment on the baby’s rash and pinned on a clean diaper. Rebecca sang a lullaby in Yiddish that Bubbie had sung to all her grandchildren: “Ay-lu-lu, Ay-lu-lu…” But even the haunting refrain didn’t calm the crying baby.

Sophie and Sadie had gone to their friend Lucy’s apartment to work on their math lessons. Benny and Papa had gone to visit Uncle Jacob and Aunt Fanny in Brooklyn. Victor, however, was seated at the table. He covered his ears with his hands. “How can I catch up on my homework with all this noise?” he complained.

Mama wrapped Nora back in her blankets. “Why not take her to the park, Beckie. It’s not far, and the fresh air may help calm her down.”

“I’ll go with her,” Victor offered suddenly. “I need some fresh air, too.”

“No,” Mama replied firmly. “Papa says you may not go out today until all of your homework is done. You have neglected too many assignments, so now you must spend the afternoon studying.”

Victor groaned.

“Come back in an hour—sooner, of course, if Nora keeps crying,” Mama told Rebecca. “Here, let me pack a lunch to take with you.”

Victor glared at Rebecca. She fluttered her fingers in a little wave as she left the apartment with Nora in her arms.

Rebecca settled Nora in the buggy and headed to the park. It was a crisp autumn day, with pale sunshine lighting the brick buildings and rutted streets of Rebecca’s neighborhood. As she entered the park, a cool breeze rustled the dry leaves on the trees. Rebecca felt grown up trundling the old buggy along and then sitting on a bench with all the mothers and big sisters, rocking the buggy until Nora finally napped. Now she was enjoying herself! She remembered how she had helped Mama push their buggy to this same park when Benny was a baby.

She opened the grease paper and took out the bread and cheese Mama had given her. As she ate, she looked around at the other children playing in the park. Some were swinging or rolling hoops along the paths, and some were throwing balls on the grass. Some were by the pond, tossing bread to the ducks.

“Save some of your lunch to feed the ducks,” said a voice at her side, and Rebecca turned to see a girl standing there—a girl just about her own age with a baby slung on her hip, wrapped in a shawl. The girl licked a dripping ice cream cone. “I am Francesca,” she said. “This is my sister, Vincenza. What is your name?”

“I’m Rebecca,” she replied. She could tell from the girl’s accent that she was not originally from New York City. “Where are you from?”

“I come from Italy,” said the girl. “Vincenza, she is born here. She come from America!” Francesca offered Rebecca a bite of her ice cream cone. “You like?”

Tentatively, Rebecca leaned over and licked it. The sweet, cold ice cream melted in her mouth. “It’s delicious!”

Francesca beamed. “Go on—you eat the rest.”

“Why, thank you!” Rebecca took the dripping cone. In the buggy, Nora started fussing again.

“Is your sister?” asked Francesca, leaning over the buggy.

“Oh, no. I’m just minding her for a while.”

Francesca spread out a blanket on the grass and beckoned for Rebecca to join her. Francesca untied the shawl and lowered her baby sister to the blanket. The dark-eyed baby kicked happily and cooed up at her big sister. In the buggy, Nora was crying harder.

“Your baby, she like to play with my sister?” asked Francesca, leaning over the buggy.

“I don’t think so,” said Rebecca. “She’s pretty fussy. I’d better take her home—oh, wait!” she cautioned as Francesca reached into the buggy and lifted Nora out. Now Nora would probably fuss even more. But no—the Brodskys’ baby stared at Francesca, round-eyed, and stopped crying.

“She likes you,” said Rebecca.

“I like babies,” said Francesca simply, and she laid Nora on the blanket next to Vincenza.

“They look like sisters,” Rebecca remarked, admiring the babies’ black curls and dark eyes. They were both wearing long white flannel nightgowns. The breeze grew brisk, so she tucked the blanket from Nora’s buggy over both infants to keep them warm. “They could almost be twins, like my big sisters—oh!” she broke off as a red ball bounced across the blanket.

Francesca caught it and tossed it to a boy standing by the duck pond with a puppy frolicking at his side. Rebecca glanced at him, and then looked again. Why, it was the same boy she had seen at the shop! Was he following her? But how could he be, when she had just arrived, and he was already playing here?

When he saw Rebecca looking at him, he grinned, and then he turned away and threw the ball into the pond. The puppy dove in and swam to retrieve it.

“You know this boy?” Francesca asked. “Go and play with dog! I watch babies. You go!”

“Oh, no,” said Rebecca. “I don’t know that boy—I just saw him earlier.”

There was a silence between the girls as they watched the boy and the puppy at play. With both babies napping peacefully on the blanket, it was pleasant to sit in the autumn sunshine. Rebecca wondered where Francesca lived and was just about to ask when Francesca spoke first.

“I have seven brothers and one sister,” she said. “What about you?”

“Seven brothers!” exclaimed Rebecca. “I have only two brothers and two sisters.”

“And school? You like?”

“Yes, most of the time,” said Rebecca. “Do you like your school?”

“I have nice teacher,” said Francesca. “She helping me learn English. She say I will speak perfect English when I grow up.”

“I’m sure you will,” Rebecca said warmly. “My cousin Ana hardly knew any English when she came here from Russia, and now she’s doing just fine.”

“When I grow up,” said Francesca, watching the boy with the puppy, “I want to be fine dressmaker, make beautiful clothes.”

“I want to be a movie actress,” Rebecca confided. Her family always said she had a flair for drama, and once she’d even visited a movie studio and played a small part in a movie. But her parents wanted her to become a teacher.

“I make beautiful costumes for your movies!” Francesca plucked at Rebecca’s sleeve. “My neighbor, she is teaching me,” she added proudly. Francesca told Rebecca that she hoped soon to be able to make all her own clothes and clothes for everyone in her family. “I practicing every day,” she added. “And look here, I sew the corno into the hem.” She turned up the edge of her skirt to show Rebecca a little hand-stitched animal horn in gold embroidery thread. “Is for a blessing. Against the, how you say? The evil eye—to keep us healthy. Some people wear a corno necklace of gold or silver for good luck, but we—we sell our…our everything to pay for boat to America. My mama, she say that not matter—a charm of thread is working just as well.”

“It’s so pretty.” Rebecca knew that some Americans carried a rabbit’s foot in their pocket for luck. Bubbie said that in Russia people painted intricate designs on eggs to ward off trouble. The Irish had four-leaf clovers. Maybe Mrs. Brodsky should sew a little Italian blessing onto the hem of Nora’s nightgown, Rebecca thought with a smile. Perhaps that would make the fretful baby stronger and healthier.

Then she remembered Mrs. Brodsky’s eyes. She was just about to tell Francesca about poor Mrs. Brodsky, who used to be a dressmaker but could no longer see to sew, when a policeman started walking up the path toward the girls, and Francesca clutched Rebecca’s arm.

“Quick!” Francesca hissed. “Hide!