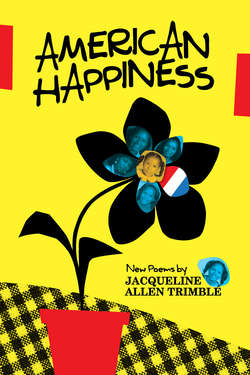

Читать книгу American Happiness - Jacqueline Trimble - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

How My Mother

Taught Me to Write Poems

My mother was a foot soldier in the fight for civil rights, had a cross burned on her lawn, drove students to Lanier, a local high school, to integrate it, and was sued along with CBS for comments she made on television. She was unafraid, dignified, and determined. My mother was never loud. I don’t remember her ever raising her voice, but she had a way of saying things that made the listener acquiesce. All the black women of that generation I knew could do that. They might have used the interrogative form, but there was never any doubt of the command underneath the question. When my mother asked, “Are you wearing that?” or “Are you speaking to me?” I immediately changed into something more presentable or altered my tone.

She could spell most any word, having studied Latin for seven years and translated Julius Caesar’s battles. “Don’t say Massatwosettes like the governor,” she would say, “Say, Massachusetts,” emphasizing the chew in the middle. “Do not imitate these little white children you go to school with and those awful twangs. You must speak well.” She liked curse words, but only in private and among very close friends. And whoever received the largesse of her choice words knew that he or she been cussed. She reminded me that though she was a widow woman raising a child on her own, we could never be poor because we were educated and had come from a long line of educated and refined people who had never bowed to anyone and never would. When a professor used me as an example, suggesting my grandfather surely had been a sharecropper, she said, “You tell him your grandfather was a teacher and a storeowner. He and your grandmother recited poetry to their children. They owned their own land, had a painted house, and the first car of anyone, black or white, in the community.”

In the fall of 1968, I went to Edward T. Davis Elementary. My mother made sure of it. My father had died earlier that year, and my mother, who was actually my stepmother, was determined to raise me as she thought my father would have wanted. That meant I was going to get the best education she could find. I was going to be well-rounded. I would take ballet and piano and belong to social clubs to learn decorum. And though I was more of a tomboy than a princess, I was going to be a lady. Most of all, I was going to know that I was as smart, as worthy, and as good as any other human in this world or the next, despite any messages I would get from some in Montgomery, Alabama.

So, I became the only black child in Davis Elementary that year. I joined the Brownies, and my mother joined the PTA. Whatever minor skirmishes or major wars ensued behind my being at that school, I never heard of them. In those days, children minded children’s business and adults minded their own. Neither inquired about the doings of the other. What I do know is that fall my mother volunteered to read palms at the fall festival. Dressed in a long flowing skirt and a peasant blouse, she played the part of fortune teller. Children and adults alike entered her small booth to have Mama gaze into her magic eight ball and tell their future. I went dressed as a ghost. There I was. The only little black child in the whole school wandering the halls of the festival in a sheet with a pointed pillow case hat in which my mother had cut two little eyeholes. It was years before I understood why my mother laughed and laughed and took so many pictures of me in my white sheet that night. Even then she was teaching me the power and pleasure of ironic juxtaposition—a lesson that continues to inform my sense of humor as well as my poetry.