Читать книгу My Beautiful Bus - Jacques Jouet - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIf it so happened that I had to decide, among the legible world’s variety of propositions, or more specifically among those candidates under the category of road signs, which legible suggestion deserves to be called the most counter-logical and disarming, then it turns out I wouldn’t have much trouble.

It isn’t unusual to discover, along roads of all sorts, this odd triangular image that the authorities have erected in plain view—

—signaling a crossing for aroused deer running at full speed, which drivers must avoid hitting, even though everyone knows that at such locations the average driver will hardly ever see the slightest trace of one.

On the other hand, I’ve never come across a sign like this one—

NO

DUMPING

—which doesn’t seem to have compensated for its absence of images with the inevitable reality lying below it, a pile of trash, foodmechanical waste, debris, and printed material, which no longer signify by themselves, a sort of illiterate provocation aimed at overly abstract or arbitrary prohibitions.

For my part, if I’ve announced anything on the cover of my book that won’t actually appear in these pages, it can only be my name—and not just my name, but also the possessive pronoun modifying the bus . . . as if I hadn’t recalled Pascal:

Certain authors, speaking of their works, say, “My book,” “My commentary,” “My history,” etc.” They resemble middle-class people who have a house of their own, and always have “My house” on their tongue. They would do better to say: “Our book,” “Our commentary,” “Our history,” etc., because there is in them usually more of other people’s than their own. 1

On the contrary, what have I not put on this cover that may indeed appear in these pages? That’s my first question. And for the reader who reads only the warning labels and then puts the book aside, well, that’s too bad. This book won’t be the one that garners more than my normal share of five hundred readers or earns royalties beyond my advance.

I supplied the label “novel” reluctantly. Even though writers have only recently been expected to give their books these labels, I’m naïve enough to be proud of my denial of this new practice. The reason is simple: I’m searching for a new form for narrative. In it, fiction will be the object of a conquest, a campaign in which the reader will be enlisted, though first he’ll be asked to endure a few pages of training, explanations of story and strategy.

Who wouldn’t enjoy slipping into the imaginative tale? One moment you aren’t there yet (just as when, not so long ago, you’d have to wait through newsreels and cartoons at the movie theater), and the next you’re right in the middle of it. Are you there yet?—Well, if I’m not, then please put me there. And if I’m in too deep, please come and join me, to share the experience or pull me out.

We aren’t looking for fiction, but rather the search for fiction. When fiction is too commandeering, it becomes nothing but mere brutality. Continuous fiction is boring. The chase is better than the catch.

They do not know that it is the chase, and not the quarry, which they seek. 2

At this point, the story will follow some paths that may appear whimsical on the surface. It will follow changes in the landscape and the seasons. A closer look will reveal that the narrative is, in fact, rigorously following logical paths that it is unaware of, or that the current page is hiding.

What do the Republic’s road-maintenance crews dream of while hunched over their tools? They dream of dreams. And what other things do the ticket inspectors and the mechanics dream of? And what about the bus drivers? Bus drivers—and their passengers—dream of buses, or of anything else that their vehicles’ attributes allow. And if they always dream of a more beautiful bus, then at least one example in particular must be the starting point, and more precisely the closest one—their own. Or maybe they dream about who owns the rows of crops they see through its windows.

My beautiful bus is in its garage in Châtillon, a garage that suits its dimensions perfectly. There isn’t enough space for two like it. It’s sheltered. It doesn’t sleep on its side.

The driver of this beautiful bus is sleeping in a nearby hotel room. The Levant hotel has only six rooms, each one of them modest. On the wallpaper, a team of white horses repeats itself. There’s a light bulb on the ceiling, in a glass globe, and a little neon light on the bedside table. The man takes up one half of a double bed. The right half remains empty, reserved for an absent companion. He sleeps in pajamas, with one arm covering his face, his nose wedged in the fold of his arm. He swallows continuously, as if he were dry-mouthed, thirsting for a drink.

An electronic alarm clock on the bedside table goes off at six o’clock, as it had been set to do. A few seconds later, in turn, the nearby church strikes six long notes. Why doesn’t the town hall sound its bell?

The driver uses Basile as his only name, and is twenty-five years into his career. He doesn’t live in Châtillon, but in a town eighty kilometers away, somewhere along the national highway. Every time he drives by his own quaint little house, he honks as a sort of hello to his wife, their daughter, the cat, and his garden gnomes.

Basile has slept in Châtillon on his company’s dime, as he does each time he gets in late and needs to leave again at dawn.

A trip home would add too many kilometers and drastically diminish the day’s profits to a break-even outcome. When work is scarce, you do what you need to do.

During these nights, Basile continues to drive in his sleep. In the morning, upon waking, he intently makes his way to the bathroom. He keeps his eyes closed for as long as possible. Basile washes himself from head to toe. He opens his eyes. He shaves and brushes his teeth. Once showered, he rediscovers his face in the mirror. He rediscovers his name, and then his wife’s: Odile. He slips into his overalls. He folds the alarm clock into his pajamas and packs everything in a travel bag.

Between the hotel and the garage, hardly 200 meters by foot, Basile doesn’t see the least bit of Châtillon, not a soul among its thousand or so inhabitants. He doesn’t notice its 900-meter elevation, its ruins of a Templar stronghold, or the second-rate RV campground . . . He’s thinking through the things he has to take care of before the departure, his routine.

Basile pampers the beautiful bus before departing. It rained yesterday and the lane-expansion project on the highway made for a muddy trip. There hadn’t been any triangular road signs carrying the inscription MUD, which would have been spelled out of course, since a graphic depicting mud doesn’t exist.

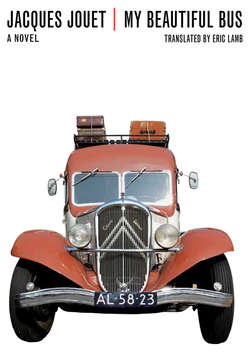

My beautiful bus is two-and-a-half years old. It’s a hardy vehicle that Basile himself has tamed. It’s a VH 300 with a standard wheelbase, forty-nine non-adjustable seats plus the driver’s (the nine folding seats were taken out), a six-cylinder engine, a passenger door, a lateral exit, and luggage compartments on each side. It’s equipped with hydraulic power steering.

My beautiful bus is lavender blue with white stripes. Its sunshades are the same faded blue. On winter mornings its exhaust is sometimes blue.

Relatively speaking, the bus driver is older than his vehicle. He’s only eight years away from retirement, and his increasingly frequent medical checkups yield healthy results: they’ve been checking his heart, reflexes, sight, and hearing.

When Basile, who’s an early riser, is at last prepared for all the eventualities imaginable in his line of work, he attends to his vehicle. In the garage, the bucket sits in its place under the faucet, and the rags sit in theirs, as well as the paper towels and the sprinkler head, which is attached to a hollow metal broom handle . . . The parts of the bus that Basile cleans: the windshield, the headlights, the taillights, the mirrors, the luggage compartment handles, and the passenger windows. What Basile polishes: the steering wheel. What Basile changes from time to time: the headrest covers.

The tires—the air pressure and wear—and the brakes are checked regularly . . . Basile takes to his job with the required sense of responsibility. He doesn’t abandon his role as a link between citizens. He doesn’t talk about things he doesn’t know about.

A driver who doesn’t reach beyond his pedals!

When I first started dealing with Basile and the beautiful bus, I was discouraged because I wasn’t sure what to make them dream about, as if I hadn’t consulted Perrault: no matter how it looks, we shouldn’t move from the story toward morals, nor should we sneak from morals toward the story, rather, we should progress from openly self-conscious reflection toward the invented story, with provocation as its only end: a story is unique, it generally has nothing to show, nothing to represent, other than what could potentially be real.

The word, the world . . .

When you speak of the wolf, you see its tail . . . In this case, language affirms its power to pull the hood off something, and affirms its skill in uncovering what convention has inadvertently stashed away, enhancing the meaning with warmth and sarcasm, if we’re dealing with literature. However, it shouldn’t be forgotten that in certain highly contradictory hotels, boiling hot water won’t come out of the faucet unless you turn the blue knob, a cold color. It shouldn’t be forgotten that in the reader’s apartment, which the author has asked to enter, the author believes that he wields all the power (including the power to gain the complicity of the reader, for which the latter isn’t even awarded a discount on the visit and the thin volume left behind). In the majority of cases, the author takes this power for granted.

If the wolf ’s malicious paw must be forgiven just a little, and the listener fooled to however small a degree—just as Puss in Boots plays dead to catch mice—then it would be helpful to look to Perrault first, to read and reread Puss in Boots, and, before saying a word, to carefully mull over the delightful formula:

“Here you are, sire, a cottontail rabbit . . .”

Puss in Boots is not a cat. He would have four boots if he were a cat. Puss in Boots is the author of an adventure, and it may well be that the narrative cat’s got his tongue for the rest of his life.

Let’s sum the story up.

Times are tough, and the setting is a mill in the impoverished countryside. The miller dies, leaving behind three children. The eldest and the middle child band together to secure inheritance of the means of production and trade—the mill and the donkey. But the least fortunate of the three heirs, the youngest, is left to starve, day in, day out.

As each day fails to satiate him, he remembers the previous evening’s brewing hunger; he’s still hungry for the following day, and the day after that, and so on until eternity. Even if he were to skin and eat his whole inheritance, a cat, he would still be hungry. That cat, Puss in Boots, swings a satchel over his shoulder, puts boots on his feet, and sets off on a hunt. He tricks a rabbit into his trap.

. . . pulling the strings immediately, he caught it and killed it

without mercy.

Proud of his catch, he headed to the king’s estate and asked to speak with him. He was brought up to His Majesty’s chamber where, having entered, he bowed graciously to the king and said to him:

“Here you are, sire, a cottontail rabbit [ . . . ]”

At this point, Puss in Boots inverts the “natural” logic of the narrative (the future Carabas is hungry; the rabbit should have gone straight to him), which numerous manipulations of the story—a temptation to which too many pen-pushers and editors have succumbed—rush to modify at this precise point in Perrault’s text. Among the manipulators, many tend to fill in the blanks strategically put in place by Perrault’s use of the ellipsis:

Surely you are thinking that the cat will hurriedly bounce home to his master and bring him his catch. But here, you are completely mistaken. Our hunter had other plans, and it wasn’t toward his master’s little cottage that he was headed.

(Puss in Boots, from Perrault, ed. Hemma, Paris, 1956.)

Here’s a second example among the many appalling modifications:

“I am going to go for a jaunt in the woods. Wait for me, master.” When the cat returns a few moments later: “Look, master. I have caught a beautiful rabbit.” “What shall we do? Eat it?” “Why no, master. I will now bring it to the king.”

(Le Chat Botté, livre-disque, Touret, 1977.)

In this third example, it’s carefully made known that first and foremost the king is a gourmet:

He swung his bag over his shoulder and headed toward the royal castle, for he had heard that the king had a vice for rabbit pâté.

(Le Chat botté, éd. Fernand Nathan, Paris, 1974, images et texte de Jacques Galan.)

All of these dubious manipulations attempt to spare the reader—and the fact that the proverbial reader is a child is no excuse—from a confusing twist that is supposedly beyond his grasp. However, it’s at this precise moment that the story winds through a surprise acceleration, which is the master stroke of a masterpiece. The same narrative craftiness predates Perrault in Facetious Nights by the Italian storyteller Straparola, in which the primordial Puss in Boots can be found.3 But this tale is more diluted on the whole. By contrast, Perrault delivers the story with a brisk, irrefutable stroke of the pen. And here we find what Master Charles masters: insinuation, relaxation, patience, and rhythm.

It’s very clear to me that this subtle jostling of the reader and his lazy habits is one of the secrets behind a beautiful story. Perrault catches up to Pascal on this point: trickery and strategy are more powerful than the cottontail rabbit itself, which is in no way useful in the practical sense (even if it does turn out that the king delights in a dish of rabbit pâté, presumably that’s not a luxury or a rare delicacy for him), but rather which acts as a testimony, from one hunter to another, of an equality of privileges, sets the rise of a future nobleman off to a good start, and leads to a climb in social standing by the main character, which is one of the story’s themes.

Following the advice of his John-the-Baptist cat, the youngest and most miserable of the heirs—you and me, or, in other words, us—who doesn’t even have a Christian name, undresses and dives into the river. As soon as he emerges from its depths, he becomes the newly christened Carabas, who climbs into a carriage, dressed differently, and rides through the countryside collecting fruits and grains, wrenched with the help of repeated blackmail from the mouths of working peasants cowed by Puss in Boots’s warning that he will dice them up into pâté.

In Memoirs of My Life, Charles Perrault boasts about having been instrumental in convincing the gentlemen from Port-Royal to see the importance of directly addressing the public outside the Sorbonne in order to keep them informed of the Jansenist-Jesuit dispute. “The First Letter Written to a Provincial by One of His Friends” came as a result of this advice, and was followed by seventeen others, written by an anonymous, progressive Pascal. Which leads me—straddling seven leagues in a single stride, and this time allowing Pascal to catch up to Perrault—to compare and mix together, as a mortar for my verbal construction site, five-shilling coaches and char-à-bancs.

In this letter, Blaise Pascal, with the help of his childhood friend Artus de Roannez and some others, conceives the democratic vision of a Parisian omnibus, even though he, like everyone else, had always ridden on coaches, the bus rides of the Grand Siècle that covered the expanses of land and water between Clermont and Paris—Pascal, who is unable to extinguish his ambition and inventiveness, who accuses Aristotle and the prophets of double standards in the vast yet confined space where he may contradict authority, who is unmatched as he discovers and fires and forges the sentences of his logical proofs, so many of which have entered into the French language (there are times when it’s appropriate to call Pascal Pascal, and others where it’s more fitting to call him the Master Wordsmith), and to such a degree that he doesn’t know how to finish The Apology under the weight of his own specious reasoning. It’s possible that Pascal’s tendency toward incompletion isn’t as involuntary as I would have thought at first, as the pascal, a noun that represents a unit of pressure in physics, is better than the adjective attached to the lamb of God, anyway this Pascal is for everyone, favoring the transportation of individuals without, theoretically, considering rank (omnibus means everyone’s bus, from the king to the poor miller’s youngster), but the royal privilege excludes “soldiers, pages, lackeys, and other liveries or individuals in uniform, as well as unskilled workers and laborers,” an exclusion of rights already established by the five-shilling fare. It’s clearly stipulated in the Letters Patent that each passenger should pay for a seat at a fixed price, five shillings and never more, whether the vehicle be full or almost empty. Hence on the 21st of March, 1662, Madame Périer, Blaise Pascal’s sister, shares the good news about the success of the coaches with Arnauld de Pomponne: “The thing hath beheld so great a success, that as early as the first morning we witnessed full coaches and even the presence of some ladies [ . . . ] .”

Elsewhere, the noun carabas is documented (Littré, along with Trésor de la Langue Française and Larousse, still recognize the spelling “carrabat”) as a possible distortion of “char-à-banc,” an open-topped public transportation wagon with bench seats, like the wagon that was used during the Age of Enlightenment to load twenty people in Paris and bring them on a four-and-a-half-hour-long trip to Versailles.

In turn, the Parisian Regional Transportation Authority (RATP) circulated an advertising leaflet in 1986 to promote its late-night buses, using the slogan, “After midnight, don’t go home in a pumpkin anymore.” Anyway, hop on!

Pshshshsh . . .

For Basile, “on time” always means early. He’s always itching to know what time it is. Managing time is his purpose in life. That schedule to follow. Those kilometers to cover while staying focused on the minutes: to not be late, or too early. Ever since his first days in the driver’s seat, he has always seen the steering wheel as a clock: “Hold the steering wheel with your hands at a quarter past nine or at 10:10.” His arms have become the hour and the minute hand.

On the dashboard, no bobble-head dolls slide around, no pin-up or dried flower hangs from the rearview mirror, no family photo, no Saint Christopher medallion or any other miraculous coin. I see Basile as a sober sentimentalist who keeps his affections secret and who has never felt hatred.

The world is at his feet and unfurls beneath them. Floating, Basile slurps up the ribbon of the road. In the rearview mirror, he gazes at the road gone by in the same way you might contemplate faraway stars on a clear night: the image seen is ancient. It goes by too quickly, or not quickly enough. The good-bye to his wife standing in their little yard where she cares for the roses—too quickly. Not quickly enough—the newly plowed plains where nothing grows yet, at least to the naked eye. If he wanted to, he could, on demand, relive the best days of his life. It wouldn’t take long to add them up.

Basile isn’t an unhappy man. He’s conscious of his fragility. To force the contrast of an exception, like tossing a stone in calm water to make things out more clearly, I presume that he carries an old wound, a small preoccupation that pulls at him like a void—might it be taking him over?—a wound he himself has patiently invented a method for coping with.

The engine warms up. The bus is ready. Basile backs it slowly out of the garage. He makes his way across the sleeping town, squeezing through the narrow streets. Oh, the mill is quiet! In a series of delicate maneuvers and turns whose geometry he knows by heart, he brushes by heavy stone façades and shutters that are still closed. Here and there, a kitchen timidly chooses the right moment to light up.

Everything is dark, cold, and hungry.

Basile parks his bus at the little square. The cafe is lit up. Three regulars have already started their day, sitting like pillars, hunched over with their elbows glued to the bar.

Pshhhh . . .

While Basile goes in to sip a large black coffee and eat a slice of toast, the bus’s engine continues to warm up. The passenger door is left open for air circulation, in the front, on the right. Anyone could hop on.

And so we hopped on, aspiring to act as a witness, wanting to sit back and observe. We, being of royal blood, but disguised as a commoner again, as a clandestine passenger of the bus, have decided to get on for amusement, with the purpose of experiencing, without an intermediary, those we represent, calmly and harmlessly observing, giving in to the archetype of the story-book prince who doesn’t know how to rule and so takes to the streets, the souk, the marketplace, dressed like one of his subjects. The royal we, meaning I, and may it also mean you, bus specter, I hollowed out from a true I, if it’s true that in the tutelary shadow of Julio Cortázar’s Cosmoroute and in Gu Menda (Lino Ventura)’s trip down to Marseille in Le Deuxième Souffle [The Second Breath] by Jean-Pierre Melville,4 I linked Embrun and Varengeville-sur-Mer alone by bus in nine days, from the 11th to the 19th of November, 1988, of course it was an intentional stroll, but I never succumbed to the clichéd role of the wanderer, approximately 1200 kilometers, only the points of departure and arrival were explicitly set, the stops in between being determined by the caprices of exhaust pipes, but nevertheless subject to my rule of no trains, no taxis, no hitchhiking, and no car rentals: Gap, Grenoble, Valence, Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, Le Puy-en-Velay, La Chaise-Dieu, Arlanc, Vichy, Monluçon, Châteauroux, Blois, Orléans, Dreux to Saint-André-de-l’Eure was an exception (twenty-five km on foot), Évreux, Rouen, Saint-Valery-en-Caux, Varengeville-sur-Mer, all for a total of 685.20 francs in bus fares, room and board, some other standard knickknacks, and nothing really special to say about it all. It was a trip without surprises. Nothing happened. There was nothing to do except stick to the rule and try to observe, which made the trip an ordinary one. What disappointment, then, must be hiding behind the title, My Beautiful Bus! Unless a thousand things already seen and considered silently fuse with the storeroom of accumulated scenes separate from the trip. For the organized trip doesn’t rule out the unexpected. Instead it reaps the false unexpected, the exotic unexpected, the sort that you find in twenty different guidebooks whose same twenty lines compete to predict the unexpected, including the level of surprise and admiration that’s required of you, if you are worthy. The organized trip shifts perspective only slightly. Which isn’t to say, however, that I will resign myself to merely describing this shift.

We, I, who am certainly Carabas deep down, Carabas lured by his homonym noun, this simple peasant Carabas having become a fat and languid king—happiness isn’t as beautiful as the pursuit of happiness—adorned with all the ridiculousness that the proverbial meaning of the largely obsolete noun conjures: a carabas is a fake nobleman, a pretentious arriviste who quickly becomes infatuated with his title . . . Carabas, having renounced his duties, set on questioning, incognito, the lowly parts of the world to find out what’s really been learned, what the people of his kingdom are thinking. Wouldn’t it be something if it just so happened that, plain and simple, my subjects didn’t give a damn about the Koran, compared to turning forty? Or perhaps I can observe how they nourish themselves with pure wine and love, and how they cope with their romantic troubles. Like my own potential problem, for example, the one that would arise if the queen were to find out that I’m clearly a peasant, and, feeling betrayed, throw me out.

How does the common world live through its troubles? How do others go about loving, and how do they handle love when it trembles at its foundations? Can I learn something from their example?

Our invisibility in the bus, a gap, the hollow I like a fly whose veins have been sucked dry by a garden spider and who, in a nightmare, becomes a vampire, a Dracula, which means that it can now take its turn drinking the blood of others, this kind of fictional character (especially when he’s the narrator), is zombie-like. If it looks like blood is flowing through his veins, it’s really just water dyed red. While watching the Disney Channel yesterday, I giddily jotted down an implicit reflection on this I character: in the Walt Disney version of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, Scrooge McDuck is Scrooge, Donald is the nephew, and Mickey is Bob Cratchit. But Mickey also plays Paul Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice, based on Goethe . . . I immediately found myself imagining Mickey Mouse as Puss in Boots, a beautiful contradiction that might pass unnoticed given the strange role that this sort of character plays. (It would be the same sort of alchemy if Charlot—not his American persona, Chaplin—were to play Jesus, for example.) He isn’t exactly an actor playing a character, because this actor is already a character, but more precisely a multidimensional character, who’s nevertheless still contained by the dimensions of his sort, loosely employed, readily hosting an array of characters in his mold. There’s something similar about my narrator, I. He has to be a stereotype, a jack-of-all-trades, capable of seeing everything and being in every situation, without ever failing to keep a distance, the least burdened as possible, from the author’s idiosyncrasies, refusing to give in to them or at least resisting them as much as possible. But this can’t be done. An author doesn’t know how to hide himself behind his characters. Instead he shows himself naked through them, and rhymes with them all.

And so I’ve embarked. Which seat should I pick? The one that’s best for stretching my legs or the one best suited for propping my knees up at eye level against the back of the seat in front of me? The one that offers the best view of the landscape or the passengers or the driver? A window seat halfway back on the left? Up front on the right for the conversation? In the very back with the middle-schoolers? Actually, I have the luxury of changing seats as I wish, without being noticed or suspected. So, it’s decided: I will read, as if this were a book, everything that would ordinarily be kept secret. And I will try, naïvely, to learn some lessons from it all.

As soon as you get on the bus, you’re greeted with three rules clearly posted on a written sign: no smoking, no talking to the driver, and no exiting the bus while in motion. Hello, good listener and good reader!

The second rule is rendered unnecessary by the bus driver’s own attitude. He certainly must hear what his customers say to him: a hello, a good-bye, an expressed curiosity, and the destination, for which he must calculate the correct amount due. Basile hands over the right tickets, hands back the change, gives a “thanks” with a nod of his head, and moves on to the next customer, but he never answers questions.

“Where are we headed?”

It’s written on the sign on the front of the bus. “Where are we coming from?”

Is it possible to know where one is coming from, at a point somewhere between the chicken and the egg?

“Where are we?”

You should know just as well I do, you who have consciously boarded the bus at this precise location.

Basile remains silent. Everyone knows this. But although he’s silent, he isn’t completely mute. He speaks with his habits. Basile doesn’t sing, doesn’t yell at the road or his vehicle, other drivers, or the cops. He doesn’t disseminate the usual banalities. He doesn’t hold long conversations about the unpredictability of our era. Basile is far away.

Pshhhh.

It’s departure time. Mechanically, Basile has already checked behind him to see if the little steel hammer is in its place, the one used to break the windows in an emergency. Everything is in order. Someone has boarded alone, an ordinary, older woman who’s too warmly dressed for the trip, headed out to kill a few hours in the next village along the bus route. She will take her time making her way back.

The bus will remain mostly empty during the first part of the trip, which is still very mountainous: short distances connecting small villages, and short stops for a single person here and there. To win over his passengers, a driver must know when to let one of them off between two official stops, or even when to let one on at the end of a dirt trail. He also has to agree to deliver packages, boxes, foodstuffs, and newspapers. Sometimes, in spite of all of his efforts and his many years of experience, Basile arrives at a village stop early. He has to wait for the exact departure time, with the bus door open, scanning the empty landscape for a sign of a passenger, a regular, rushing to catch the bus. Most of the time, no one comes. Or someone will be waiting half a kilometer away to flag him down.

We’re still winding through the narrow part of the route, heading down from the pass, the part of the journey that never seems to end. The undergrowth is moist here. Rocks tumble from the steep slopes and roll onto the road. The slope on the shady side is mushroom-laden. With a bit of luck you might spot a squirrel scurrying about, darting incessantly in all directions, and, perhaps once every ten years, a bold pair of mountain goats. It’s the icy part of the route when winter insists on it, the part where you feel sick in the morning on an empty stomach, and the part where the sun makes glorious halos two months out of the year at a precise time of the day, piercing through the fog and the trembling leaves.

It’s autumn today. Summer has been left behind in the rearview mirror. At high elevations, yellow needles fall, dying, from larches. The chestnut trees still hold on to half of their leaves. Further down, the oak trees will cling to their browned and wilted leaves until springtime.

Most of the time, passengers hardly look at one another. But look here, two are saying hi . . . I move closer and hear them whispering about their driver:

“He isn’t talking any more than last time.”

“Or any of the times before.” “Seeing how long this has gone on, I’m of the opinion that he won’t ever speak again.”

Which seems to suggest that he’s talked in the past. “A hopeless case.”

As we get closer to the midpoint between the two small towns, Châtillon and the stop at La Chapelle-something-or-other, we begin to enter a zone of heightened magnetization. It feels as if everything that lives and feels, out of habit or by impulse, everything that admires or desires, is moving toward the town ahead. The effect of this phenomenon is a considerable increase in bus passengers.

In the courtyard of a saw-mill, a fire burns incessantly, fueled by wood chips and sawdust. Even the smoke flows in the same direction as my beautiful bus. The cry of the biting saw is earsplitting.

Basile turns on the radio to listen to the daily news. What’s on today? Reports follow each other like days, and look a lot like one another: the famous are ill prepared for their inevitable obscurity; foreign trade is reviving; the weather is peremptory. There’s a death toll; Basile hears the total and turns it off.

School is about to start and it’s time to pick up all the classroom-bound-kids along the road to La Chapelle. It’s conceivable that there’s a big middle school there, since the stops are taking longer and the columns of twelve-to-fifteen-year olds are getting longer. The time must be taken to slide a few big bags into the luggage compartment. The school kids open and close the compartment door on their own. They board in bunches. There’s the cocky kid, armed with a sole flap folder decorated with a garish sticker expressing his disdain for bulky schoolbags. There are those who rush toward the very back, the loudmouth boys with their little tiffs about who’s on top. A girl has the right (or the cheek) to join them. She has entrusted her small backpack to her friend who has stayed up front, who isn’t as pretty, and therefore doesn’t have the same privileges . . . she resigns herself to isolation, but not without the pride of becoming, after the incident, a trustworthy confidante.

Basile daydreams about his daughter, their daughter, who drifted away from their world, moving further and further away day by day. This was necessary for her to be able to grow up, receive her high school diploma, and leave for Paris to study business. Everyone wants to study business these days. He broods over the vague fear that they may never become close again. An autumn feeling . . . like spring will never be seen again, out on the horizon, through the windshield. In his bus, Basile passes the house that he built fifteen years before, very slowly, brick by brick, he even got his own hands dirty in order to reduce the cost of the enormous project, completing all of the finishing touches on his own. How time flies! Not a leaf is left on the tree. He honks his horn, a greeting to the smoke drifting from the chimney, signaling that the central heating has turned on. He’s well aware that there’s no one inside the house and that the electronic salvation must have been triggered by the drop in temperature. The rose bushes that he has dressed with straw are ready for the tough season. The boxwoods sometimes freeze over. It snows on the gnomes. In the rearview mirror, once it has been passed by, the house is newer, the trees aren’t as tall, the renderings are radiant; everything appears like it was not so long ago.

Basile isn’t the kind of driver who goes out of his way to entertain the middle-schoolers. No zigzags through detours. No radio liberating its sound waves. Sometimes, during easy-listening hour, he’s willing to understand the silence from a little girl passenger patiently standing beside him as a question, and answers yes by turning the radio on at a very low volume, as if with his own voice he were whispering a song in her ear.

More and more adolescents get on. After a few more stops, there won’t be enough seats for everyone. Some will have to stand in the aisle, keeping their balance by holding on to the handrails. My beautiful bus shakes its passengers when it rolls over a speed bump, known to some as a sleeping policeman. Fog begins to film the windows on the inside due to the combined effects of breathing, conversation, and laughter.

At a village stop, before the recent rush of passengers got on, a young woman boarded the bus through the side door. She didn’t buy a ticket. She didn’t show a bus pass. She waved to Basile from a distance, communicating some kind of understanding between them. Some middle-schoolers, for the most part girls, say a shy hello to her, but keep their distance. She places a leather briefcase on the seat next to her. She will have to hold it in her lap soon. I’m immediately drawn to this passenger: she’s beautiful without being too beautiful, small and of an indefinite age; she’s smiling and curious about these people around her who are so easily surprised by nothing, and ask questions about this nothing until they find their special secret, always lying in wait for a slice of conversational pleasure. They will always find at least some pleasure. I have never seen her before; she reminds me of someone. I recognize her right away, with the strength of a resonating echo that I have trouble pinpointing. She has one hand that I believe I know, while the other is completely foreign to me; one eye has already seduced me, while the other can hardly see me. She stirs up feelings of pain and reminds me of my troubles. She is reading a book and a newspaper, alternately. The newspaper is regional. The book is thick. She holds back a yawn.

Since she got on, Basile can’t stop looking in all of the rearview mirrors at hand, and, to that end, he even adjusts the left side-view mirror. She’s the one he’s looking at, no, observing, no, the one he’s staring at, and the one he sees change shape and get larger, but only slightly.

At one point, she smiles at him and widens her eyes, as if to say “watch the road!” or “be careful!” or even “patience!” Then she lets her gaze drift away into the expanse of scenery flying by.

The bus on the road follows a fierce flowing river. The water is grayish, a sign of violent rains upstream. Random pickets hold back grass, sentences, twigs, shredded bits of plastic, giant masses of hair, everything that the current carts along, living molecules that compose and consume stories. Public dumping is a common occurrence. The waste unabashedly finds its way down to the riverbank.

Once the road reaches a particular hamlet, Basile stops, and pshshshsh. He waits with the door open. Is someone there? No, but something is. A pot with a cover held in place by a knotted dishtowel has been delivered right to the door by a limping old man. The man doesn’t even announce what’s in the pot. It contains mushrooms, oyster mushrooms. He only says “thank you,” in a tone that implies more, that says that everything is happening as expected, a simultaneous “hello,” “good-bye,” and “it’s understood . . .” and “I know everything about you that I need to know.” Basile doesn’t say anything. He knows to whom he should pass along this seasonal commodity: to the best restaurant in La Chapelle, which has the ironic, rhyming name of La Gamelle, the Lunchbox.

The bus is packed, but it’s still a while before the empty seat next to the woman reading the book and the newspaper is filled by a young girl who is more daring than the others. Do they know each other?

“So, Nathalie . . . how have you been?” “You remember me!” “Of course! So, how are you? You’re in eighth grade, right?” “Ninth grade, ma’am.” “Already . . .” “Yep. Actually, I have a homework assignment on Baudelaire . . . I wanted to ask you . . . Am I on the right track to suggest that his prose poems . . . um, well, that they were more modern than his Flowers of Evil?”

“Modern . . . Well in any case it’s . . . Does he say that? Well, I don’t know . . . I can’t remember.”

The woman reading the book refrains from saying: “I teach fifth grade, you know.” Deep down she’s thinking that she may never have really known the answer to the girl’s question, and it makes her sad because it was nevertheless within her reach to know. She only has about two minutes to confirm the young girl’s brand-new impression that she knows a little something about literature. She settles with encouraging her, hardly daring to dream about the big city Baudelaire envisioned, his conformity to an elastic style of prose, while through the window she admires the precision of the fields of plowed rows, the meticulous planting of young crops and vineyards, which are like lines of verse on a page. She lets out a sigh:

“I’ll have to read it again . . .”

And I bet she will.

Rush hour is over. The middle school and the high school are on the outskirts of La Chapelle. The youngsters have exited the bus, slowly and wearily, carrying with them a vague anxiety hidden under too much nonchalance. The closed space of the schoolyard—which in a sense belongs to them, after all—reassures them. It opens up its doors to them daily, with no exceptions.

Against the flow of the emptying bus, a fat woman gets on. She seems like the type who’s just looking for something to complain about. She’s only going as far as downtown and regretfully takes out a few francs, as if she were being forced to give away precious stones. It’s expensive. To make sure that she gets her money’s worth, she takes up two whole seats with her big bags. She sits down in the same row as the woman reading the book, but across the aisle. She wants to chat. To get the conversation going, she talks about the driver, which apparently isn’t the best method.

“Out of all the company’s employees, I like him the best. A very gentle man . . .”

And she smiles with a look of understanding. The fat woman waits for a response to her eloquent words, which won’t come.

“And the most punctual. I’m telling you . . . It’s been more than ten years that I’ve been riding this line at least once a week, you know.”

The two women size each other up. Apparently the one who boarded most recently doesn’t like the other one’s small smile. It irritates her. It makes her realize how vain her words are. She’s the type of woman who leans in close to whisper gossip but deliberately raises her voice to make herself heard anyway.

“Is he doing alright these days?” “Oh, I don’t watch over him.” “Well, I guess you’re right not to.” “I don’t know if I’m right. But that’s the way it is.” “You’re lucky!” “Lucky . . .”

In the rearview mirror, Basile watches her answer. Does he know how to read lips?

He pulls the bus into its temporary terminus. It will make a fifteen-minute stop here. The fat woman exits the bus, grumbling. She has a hard time making it through the aisle smoothly with all of her bags, and no one helps her. That’s always the way things go nowadays. The world is becoming wild again. She makes sure to say good-bye to the driver, but not to the woman passenger with the book.

Apart from her and myself, there’s no one left on the bus. Basile comes over to her and tells her something, without speaking, something tender I believe. I can tell by the way he approaches delicately and cautiously. Pretty soon it becomes obvious that she’s the person, the Odile and the wife, for whom he has decided to reserve the surprises of an inaudible language, a language spoken by only one person in the whole world: him, but understood by another person, and one person only: her. Keep in mind that if I want to remain faithful to the role that I have set for myself, at this point I will have to learn how to translate it.

And so together they whisper to each other, in their way. They tenderly hold one another’s hand. It’s break time for both of them. Odile smiles, which is paradoxically what betrays her faint sadness. Perhaps she wants to get back to her reading, but she surrenders to the duty of being present and paying attention. She says:

“If I have the energy later, I’m going to grade some of my students’ notebooks.”

The tone in her voice hints that she’s somewhat dreading the chore, but that she’s confident nonetheless. She knows that once she’s gotten started, she will find herself completely immersed in the task, and will be ready to dote over a good assignment or congratulate herself for some evidence of progress.

“I don’t have class today. If it’s all right with you, I’ll ride along your route with you. And I’ll get off at La Ferté to see my mom.”

He has a fatalistic expression on his face. He’s surprised, from what I can tell, that she can write without difficulty in my beautiful bus.

“It’s not exactly writing . . .”

But what about reading? It makes so many passengers nauseous. They say so themselves.

“Not me.”

Would you read on top of a volcano? “Why not?”

During an air raid?

“Even on Charon’s boat, the boat that brings the dead to the other side of the river.”

A rotten line of work. “He’ll make all of us get on the boat someday.”

Not you. “Yes, even me.”

No.

Time . . . It’s about time to leave again, time for the most distant collusions, using the rearview mirror or collective memories as the intermediary, amid the usual peacefulness of a trip without surprises, if all goes according to plan.

Pshhhh.

Basile turns the key to the ignition and puts the engine in gear. The motor hums, as it’s supposed to. The turn signal blinks. The bus has the right of way as it leaves its stop. In a flash, Basile thinks about his back, the compressed vertebrae, which is a common condition in his profession. Others have it worse than he does. He thinks about the required solidarity between time and space, the Siamese twins of his toil. He awaits the sight of the mansion with a bare triangular pediment that he has watched crumble to ruins over the past twenty years, little by little, in the same spot. To keep his fear at bay, he inevitably muses on his two-part obsession, each part undoing the other: the first one involves him crushing a child under the wheels of the bus, a child that turns out to be his own daughter; second, he thinks about the punishment he would have liked to wish upon himself to prevent the first: a truck ahead of him carries a heap of scrap metal. A scrap severs the strap holding it in place, takes flight as the truck passes over a bump too quickly, passes through the windshield of my beautiful bus, and decapitates Basile the driver—a negative consequence of the fact that the new roads permit higher speed limits by bypassing the center of large towns. Fortunately, the bus, for its part, still has to pass through towns, regularly exit the national highway, slow down, and snake through the old road that all of the traffic was once forced to squeeze through. The bus has to wind its way to its stops at the plazas lined with plane trees, and be received ceremoniously as the vehicle of saving grace that opens up all of the Republic’s enclaves to the rest of the world.