Читать книгу The President's Keepers - Jacques Pauw - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One The spy in the cold

ОглавлениеHow the hell do you track down a spy in Moscow, a metropolis of 14 million residents, 7 million cars and 203 metro stations? It might have been the stamping ground of spying and counter-intelligence during the Cold War but these days it's a city on steroids where super-rich oligarchs buy Greek islands and London football clubs and commission Jennifer Lopez to perform at the weddings of their offspring. Soaring skyscrapers stand side by side with granite feats of Stalinist architecture, and Mercedes-Maybachs and Aston Martins roar past the remnants of boxy Ladas on six-lane highways.

What has happened to the armies of snoops and spooks who floated like ghouls across Red Square with bulges in their pockets and poison-tipped umbrellas in their hands; and who concocted conspiracies in hushed voices in stolovayas – Soviet government canteens – while gulping down stinky kolbasa sausages with Moskovskaya vodka?

I had just spent a substantial amount of money on an air ticket, subjected myself to a torturous flight across three continents and abandoned my new life as a chef and restaurateur in the hope of tracking down a former South African spy who I believed had a hell of a story to tell. I was like a rehabilitated drug addict who after two years of abstinence was about to stick a needle in my arm and propel heroin through my veins. I was attempting to do exactly what I had vowed never to do again: immerse myself in the seamy world and fortunes of low-lifes and charlatans, fraudsters and crooks, conmen and swindlers.

I was beset by a mixture of guilt, doubt and apprehension when we approached Moscow's Domodedovo International Airport. Under the belly of the Emirates Airbus was mounted a camera that beamed pictures of the landscape to the television screen on the back of the seat in front of me. We had flown for hundreds of kilometres over a patchwork blanket of white fields and dark woodland. I realised there is no colour in an iced landscape; it's all shades of white, grey and black. The airport was way out of the city and was surrounded by farmland and tiny villages that stood frozen in the face of daily blizzards. Cars were buried under snow and there were no signs of life except for grey smoke belching from tall, thin chimneys.

Domodedovo is an unfriendly place. After we had disembarked, I stood in a queue that snaked around silver-coloured metallic dividers. A sense of paranoia permeated the air. Border policemen clutching Kalashnikovs eyeballed arrivals with looks that could kill. I was anxious. It is notoriously difficult to get a Russian visa, especially for an independent traveller (visas have since been scrapped for South Africans). You require what is called a “visa invitation”, an official document issued by an accredited Russian travel company that confirms that you have submitted a full itinerary and that your accommodation and travel have been prepaid. I didn't have time to go through the formal channels and instead bought papers for £30 from a London-based company. I had within half an hour a bogus document in Russian, confirming a full (false) itinerary and containing a host of stamps and signatures. The Russian consulate in Cape Town accepted the invitation, but I had to take copies of my documents with me because customs in Moscow might require them.

Moscow has recently been named as the most tourist-unfriendly city in the world. There are no welcoming signs at the airport or any indication that the authorities want foreigners in their country. A blue-uniformed immigration commissar awaited me in a booth at the front of my queue. She probably came to work every day in one of those fucked-up Ladas and had a permanent frown on her forehead that was partly covered by a peroxided fringe. A set of glasses that Lenin's Bolshevik Republic issued to her grandmother balanced on her nose. She asked the passenger in front of me for a document. He scratched frantically in his bag. He was of Middle Eastern origin and I hoped that that was the reason why his documents were scrutinised. Russia was bombing Islamic State in Syria and was in the organisation's cross-hairs.

When my turn came, she studied my passport – page for page – under a magnifying glass. News might have reached the expanse between the Great Steppe and the Baltic that South African travel documents were easy to obtain on the black market. She then looked up at me, down at the passport and up at me again. Come on, comrade, I thought, it's a new passport! She scribbled for a long time and stamped many papers. Without uttering a word, she waved me through with a slapping action to face customs – an equally frightening and inquisitive lot. Outside the building I was greeted by sharp blades of icy wind that threatened to cut my face open. It was also a perplexing English-less world because every signpost, nameplate or noticeboard was in Cyrillic script. It left you bewildered, like a rudderless ship with a spinning compass in an open and hostile ocean.

It was just past three in the afternoon and a dingily bilious sun was seeping through a tent of black clouds, their bellies heavy with snow. Moscow's taxi brigades are notorious for ripping off foreigners. I approached one that wanted 8,000 rubles (about R1,700) for the journey to the hotel. He shoved a map in front of me and pointed at the distance between the airport and my hotel. I waved my hands, protested loudly in English and walked away. We settled on 3,000 rubles. He shook my hand, babbled incessantly and took swigs from a flask while swerving through the traffic and negotiating the icy roads.

Moscow's frenzied traffic was almost the only audible sound at the height of winter. Birds had long since headed south for sunnier pastures, the city's café society had emigrated indoors, playgrounds and parks were empty, and Muscovites themselves were like dark ghosts, clad in fur, wool or leather with scarves wrapped around their necks and ushanka caps on their heads and over their ears. They floated effortlessly and silently over the snowy brown sludge and cut like blades through the Arctic breeze. It was impossible to walk at their pace – as futile as trying to keep up with a Masai in the scrub and savannah of southern Kenya.

Moscow and Russia have always been high on my bucket list and I have throughout my journalism career submitted story proposals that included a trip to Russia. They were all shot down, and when I left the profession at the end of 2014, I had given up hope of ever strolling on Red Square or downing a shot of vodka in a Russian bar.

This was until November 2016, when I received a phone call from a former employee of the State Security Agency (SSA). I had last spoken to him when I was still a journalist and did a story on major corruption in the agency.

“Do you remember Arthur Fraser?” he asked me.

“The new guy at State Security?”

“That's the bugger! Well, I've got a name for you. And an e-mail address.”

“Who are you talking about?”

“The guy that did the corruption investigation into Fraser. He knows everything. His name is Paul Engelke.”

“I'm not a journalist any longer,” I told him. “I'm a chef!”

“I know,” he said. “But I thought you'd be interested. I've also been told that he might be willing to talk.”

“Why would Engelke talk?” I wanted to know. “It's dangerous for him.”

“I've been told that he had left the service and is bitter.”

“Interesting,” I said. Journalists feast on the disgruntled and those that are intent on revenge. But I wasn't a journalist any longer. I was now the owner of a 60-seater restaurant, bar and guesthouse. It was the onset of summer and the establishment was packed over weekends as Capetonians flocked to the Swartland to get married, sample award-winning wines or feast on our olives and lamb. I was also about to launch my new summer menu.

“You must send Engelke an e-mail and ask him if he will talk to you,” said the contact.

“Hmm,” I said. “And where is he?”

“Unfortunately, he's a bit far away.”

“How far?”

“He lives in Moscow.”

* * *

In October 2014, as I was about to close the chapter on my journalism life, I wrote a story for City Press under the headline “Spies plunder R1bn slush fund”. It chronicled an orgy of fraud and corruption; of how a top intelligence officer by the name of Arthur Fraser had allegedly squandered hundreds of millions of rand of taxpayers' money. Fraser, then second in command at the National Intelligence Agency (NIA, which later became the SSA), had embarked on a project to expand South Africa's intelligence capabilities. It was known as the Principal Agent Network (PAN) and had a limitless budget. Millions of rand in cash were transported in suitcases from a state money depot in Pretoria central to “the Farm” – the nickname for the agency's headquarters, otherwise known as Musanda, on the shores of the Rietvlei Dam, south of Pretoria. Much of the money in the PAN slush fund was squandered.

I had never met the bald-headed Fraser and he seldom appears in public. He was described to me as a broody, burly and soft-spoken man – he was apparently a bouncer in his younger days – who was the archetypal spy. What is the typical spy? To start with, they think that they are on a mission to save the world. The worlds of Matt Damon and Daniel Craig are slick, fast-paced and sexy. Their suits never crinkle, women always say yes, and their cars shoot missiles. Real-life spy sagas unfold with far less panache. Overseas research has shown intelligence agents at the CIA to be often college graduates with low-value degrees; they are outsiders or loners, they have family or friends in the intelligence or armed services, they can't work with money and love firearms. Much of a spy's work these days is sifting through data.

Spies and assassins are akin in that they have their own unique phrases and slang that only they understand. An assassin never kills but “eliminates”, “permanently removes a subject from society” or “makes a plan” with him. In spy lingo, a bodyguard is a babysitter, a dead drop is a secret location where material can be left, and a person can be a target, an asset or a sleeper.

Fraser remained defiant throughout the two-year investigation into him and boasted that he would never be charged. He set up a string of businesses after he resigned from the intelligence service and concluded multimillion-rand contracts with government.

There was little reaction to my exposé in City Press, which I attributed to corruption fatigue. Readers had simply had enough of the daily barrage of news of state pillage. It didn't bother me because I was about to embark on a new chapter in my life.

* * *

I was a journalist for thirty years. A columnist for a Sunday newspaper once wrote that if journalists were the “nagkardrywers” (sewage car drivers) of society, I'm grubbier than any of them. She said it is probably because I've encountered my fair share of loonies and psychos, civil war and genocide, warmongers and cut-throats, scammers and tricksters.

Hunter S. Thompson once said that journalism is a “cheap catch-all for fuckoffs and misfits – a false doorway to the backside of life, a filthy piss-ridden little hole nailed off by the building inspector, but just deep enough for a wino to curl up from the sidewalk and masturbate like a chimp in a zoo-cage”. I think he exaggerated, but my mother till her death wanted to know when I was going to get a “real job” and was convinced that there are far worthier things to do. I'm not sure if baking milktarts and cooking waterblommetjiebredie would have met her expectations either.

I left journalism as the head of investigations at Media24 newspapers. When I wrote the Fraser exposé for City Press, I was already the proud owner of a neglected guesthouse, restaurant and bar in Riebeek-Kasteel in the Western Cape. The village is a mere eighty kilometres from Cape Town and one of the province's “happening” country spots and getaways. The guesthouse cum restaurant was once one of the grande old dames of the valley; a 150-year-old manor house that guarded Riebeek-Kasteel's south-eastern entrance on Hermon Road. She had been sleeping guests, feeding strangers and quenching thirsts for two decades.

Journalist and friend Chris Marais said of me and Sam in a magazine article: “Gone, for these two, are the days of flitting through Africa with a cameraman, a notebook and a notion of a good story to be told. No more killing fields of Rwanda, drinking sessions with death squads, TV production deadlines, dodgy spaza preachers, chasing junkies through the back streets of Maputo and sailing down the Congo River on a stinky market boat. Gone, too, are the days of the generous expense account, the top-end media awards dinners, the acclaim and the sweet result of seeing the bad guy brought to book after being exposed on air.”

Riebeek-Kasteel, surrounded by tanned cornfields and green vineyards, feels as though it is thousands of miles from Gauteng. It is wall-less, tractors full of grapes roar through the village, children play in the streets, and in winter the mist tumbles and tosses down Kasteelberg. The locals are engaging and gentle, and it is the kind of place where Sam and I can live forever.

We threw all our savings and pension into our new venture. We gave her a complete facelift and rechristened her Red Tin Roof. We donned her in new colours and enlarged the bar – and then added another one. We revamped her from head to toe and decorated her with our eclectic mixture of art and collectibles that we have accumulated from around the world.

Sam and I moved into the roof of the manor house, which was used by the previous owners as a conference venue. “You know what,” Sam said to me, “we live like white trash.” We've done so ever since.

The first few months were tumultuous and at times Red Tin Roof resembled a madhouse. The whole village descended on the place on opening night. Our credit card machine didn't work and we collected wads of cash in plastic bags. I grabbed friends and shoved them behind the bar to serve customers. Others were elevated to chefs to braai sosaties and skilpadjies (a Swartland delicacy of chopped lamb's liver wrapped in stomach fat). Then Eskom switched off the electricity.

Whether by choice or not, I have since then been banned to the kitchen. I had early on proved that I lacked the social finesse to deal with customers when I told a Spanish guest to fuck off when he complained about his Dom Pedro. Problem was that he had just sat down with his extended family for a long and boozy lunch. They stormed out. The Spaniard returned the next morning and demanded an apology. He got one, but after that Sam dragged me to the kitchen and ordered me to stay there.

I think I'm a bit of a feeder, and in Ann Patchett's essay “Dinner for One, Please, James” she says: “I love to feed other people. Cooking gives me the means to make other people feel better, which in a very simple equation makes me feel better. I believe that food can be a profound means of communication, allowing me to express myself in a way that seems much deeper and more sincere than words.”

Chris Marais writes: “It's a Sunday afternoon in Riebeek-Kasteel and we've just arrived to see Jacques and Sam and get a first-hand progress report on this, their latest adventure. We sat outside in the quietening courtyard. Lunch is a distant memory, and only the last few drinkers remain with what's left in their wine bottles. It's clear to see who is ‘front of house' and who is ‘engine room'. Sam is all smiles, elegance and welcome. Jacques is all kitchen confidential, a bit like the mad genius you had to drag out of the lab and into the sunlight.”

* * *

For the first year of my self-imposed exile I happily slaved away in the Red Tin Roof kitchen. That was until December 2015, when President Jacob Zuma fired his minister of finance, Nhlanhla Nene, and replaced him with ANC backbencher Des van Rooyen. Nene was a proponent of stern fiscal discipline and cutting government spending to allow for growth and poverty alleviation. That was not the priority for Zuma. He wanted control of the state purse.

Although Van Rooyen has a postgraduate degree in economics, he had no experience in Treasury matters. He was the mayor of Merafong in 2009, but residents chased him out of the township after burning his house. He was reportedly the preferred choirboy for an Indian immigrant family known as the Guptas. Brothers Ajay, Atul and Rajesh relocated to South Africa from India's northern state of Uttar Pradesh in 1993, just as white minority rule was ending and the country was opening up to the rest of the world. They control a vast business empire (Atul is South Africa's richest black businessman) and have become notorious for the “capture” of Zuma, some of his cabinet ministers and important elements of the state.

Prior to his appointment as finance minister, Van Rooyen visited the Saxonwold, Johannesburg, compound of the Guptas seven times and made 17 phone calls to the brothers. Hours after his appointment the Guptas sent two of their business associates to be appointed as advisers to Van Rooyen. The ascendancy of an ill-qualified Gupta stooge to the most sensitive cabinet position in South Africa sent the rand into a tailspin, stocks slid and bond prices tumbled. The country lost billions of rand within 24 hours. Four days later and under enormous pressure, Zuma made an astonishing U-turn by removing Van Rooyen and reappointing the respected Pravin Gordhan as finance minister.

I was watching the spell-binding political drama with anticipation from my kitchen at Red Tin Roof. Before starting to cook and bake at five or six every morning, I scoured news sites for more information on Zuma's attempts to capture the Treasury. Like most South Africans, I realised that should a man accused of fraud and his henchmen lay their hands on the state's coffers, it would be as fatal as handing an alcoholic the keys to his local Liquor City.

Several former and current politicians and journalists visited me at Red Tin Roof, and old security and intelligence sources contacted me again. In the meantime Max du Preez, journalist, author and gabba for twenty-five years, was providing analysis and spurring me on to start writing again. He lives a stone's throw from me in Riebeek-Kasteel.

Max and I had co-founded three significant events in print and television journalism: the Afrikaans anti-apartheid newspaper Vrye Weekblad in 1988, the Truth Commission Special Report at the SABC in 1996, and the public broadcaster's premier current affairs and investigative show, Special Assignment, in 1999. We started the SABC ventures before the likes of ANC commissar Snuki Zikalala and Zuma clown Hlaudi Motsoeneng destroyed the broadcaster and turned it into a propaganda tool for the ANC.

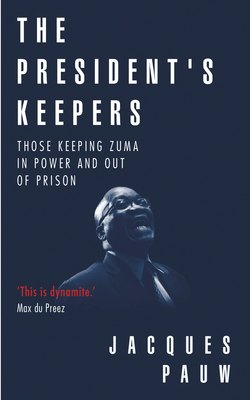

“You have to write another book,” said Max. We were sitting in a quirky restaurant called Eve's Eatery in the heart of the village when he added: “You know more about guys like this than anyone else.”

“And what should the book be about?” I asked Max.

“About the people that Zuma surrounds himself with. The Shauns and the Mdlulis and the Ntlemezas and the Jibas and the Nhlekos and the Hlaudis and the Zwanes. But also about the faceless, nameless bunch behind them that play a vital role to keep him in power.”

“And out of prison,” I added.

“Precisely,” he said.

“And don't forget that they also enable him and the family to make money,” I said. “Just think about his son's links to the Guptas and illegal tobacco smugglers.”

“There you have it,” said Max. “It's a book.”

Shortly after this lunch with Max, Arthur Fraser was appointed as the new director-general of the State Security Agency (SSA). The man implicated in a two-year forensic investigation for misappropriating hundreds of millions of rand and fingered as a possible treason suspect was now South Africa's top spy boss.

I was horrified at Fraser's appointment but neither shocked nor surprised. It was clearly payback time in return for the favour he had done the embattled Zuma almost a decade previously. Fraser had, at the very least, taken out a political insurance policy.

Fraser's rise to the top of the intelligence hierarchy must be seen against the backdrop of what I regard as the primary objective of Zuma's presidency: to stay out of prison. In order to avoid spending his last days behind bars, he has to cling to power in order to prepare an exit strategy that will guarantee his freedom. This is closely followed by his greed to fill his and his family's pockets. Cronies are welcome to help themselves but their priority is to assist him to retain his freedom. Only after Zuma has looked after himself comes the small little problem of governing the Republic and its millions and millions of hungry, uneducated and jobless voters who are looking to him for salvation and deliverance.

When I saw Max again, he said to me: “Remember what we spoke about the other day? Our conversation about the people that protect Zuma?”

“Of course I do,” I said. “I think about it often.”

“And now you have Fraser as well. There is now a Zuma person in virtually every crucial position in government.”

I told Max about the phone call from the former spook who had told me about Paul Engelke in Moscow.

“I haven't contacted him yet,” I said. “I don't know if he will speak to me.”

“Find out and if he says yes, go! Go as soon as possible,” he said. “Ek weet mos dat as jy eers daar is, gaan jy met sy kop smokkel. [I know that once there, you will get into his head.]”

* * *

I e-mailed Paul Engelke in Moscow and said who I was and that I wanted to talk to him about his investigation into Arthur Fraser. Would you see me if I come to Russia? He replied almost immediately – always a good sign – and agreed to meet me but added that he was bound by the constraints of the Intelligence Act and couldn't talk to me about anything he did as a senior SSA employee. The investigation into Fraser, he added, was top secret.

I replied that I already knew a lot about his investigation and maybe he could just confirm a few things. He said that if I came to Moscow, I had to bring a bottle of Rust en Vrede red wine, a plastic tub of Mrs Ball's and dried fruit. Russian food is bland, he complained. They add salt and nothing else. I smiled as I had just read a quote about the Russian capital that said: “You don't come to Moscow to get fat.”

“I want to write a book again,” I said to Sam on a blazingly hot afternoon on the veranda of the Red Tin Roof. Next to us bursts of white petals adorned the roses while on the other side of the fence heat waves danced on Hermon Road. She fell silent and stared at me. She had lived through the last three books and said that they had been the loneliest times of her life.

“And who is going to cook while you sit in your cosy little corner week in and week out and talk to no one?” she demanded to know.

“Fiona will cook. I'll keep an eye on the kitchen.” I said. Fiona Snyders is Red Tin Roof's chef and the heart of the kitchen. Large, gregarious and loud, Fiona has been with us from day one. When it is busy and the heat rises into the forties, Fiona is a sight to behold: a battle tank on a mission, her head perched forward and her mouth going off. She has a braai tong in one hand while a pudgy finger on the other presses against an Angus steak to determine if it is medium-rare or medium.

Sam finally conceded that I should write the book and that she would support me. “It's in you and you can't get rid of it. Go for it, otherwise you'll never be happy.”

I then bowled her my googly: “I have to go Russia. Maybe next week already.”

“To do what?”

“To see someone.”

“Who is he?”

“A former spook. He was high up in State Security and knows a hell of a lot. He lives in Moscow. I think he might talk to me. His name is Paul Engelke.”

“And for how long are you going?”

“Twelve days; maybe two weeks. I'm not sure yet.”

“Do you need two weeks to speak to one person?”

“I might need time to persuade him.”

Sam gave me one of those looks. “And don't forget to bring Olga back,” she snarled. “We can do with another waitress.”

* * *

In the drab twilight of a Russian winter with an ash-coloured sky blotting out the sun, I strolled along Red Square and past the Kremlin while waiting for Paul Engelke to contact me. Communism was long gone but the cobbles of the square still carry the echo of vast Red Army parades that rolled past Leonid Brezhnev with intercontinental ballistic missiles armed with nuclear heads that could obliterate the world. This was the core of Moscow and the square is surrounded by a series of concentric ring roads. It is almost as though power oozes from the Kremlin down the ring roads to every suburb in Moscow and beyond to every city, town and outpost in the Federation – as far as Vladivostok, nine time zones and 6,500 kilometres to the east. It is much quicker to fly from Johannesburg to Lagos than from Moscow to Vladivostok. I couldn't help thinking: can you imagine Jacob Zuma also ruling Nigeria, 4,600 kilometres to the north-west? The chaos and madness!

Every dynasty, order and ruler has added to the Kremlin. The grand dukes replaced the oak walls with a strong citadel of white limestone. The tsars imported Italian architects to reconstruct much of the Kremlin while Catherine the Great built a new palace. The communists destroyed a monastery, convent and cathedral and ultimately erected a mausoleum for Vladimir Lenin, the founder of the Russian Communist Party, after his death in 1924. Lenin's head still rests softly on a black pillow, his waxy hair and neatly trimmed ginger beard coiffed into a sharp point. He's dead but not forgotten.

Today, communist austerity, ancient history, devout orthodoxy and Russia's new capitalist indulgence live side by side on Red Square. Under communist rule, there was nothing to buy; now everything is for sale. If there was ever a capitalist finger up Lenin's waxy ass, it was the opening of the ultra-luxurious GUM store on the eastern border of the square, just a stone's throw from the mausoleum. It has become a playground for the ultra-rich and hosts brands such as Louis Vuitton, Zara, Calvin Klein and Dior.

I stumbled and slid in the snow from bar to bar, where I ordered a vodka and started compiling lists of those that keep Jacob Zuma in power and out of prison. I also noted those that keep the family's purse bulging.

Whether you have to get to the top of the Kremlin or clamber up Jacob Zuma's slithery and gangrenous pole, politics is a messy business. Everyone on that pole, from the lowest to the highest, is vying for position and trying to hoist himself or herself a little higher. In the process they make deals, stab one another in the back, plot the downfall of rivals, create alliances and latch onto those who they think will move them up the pole.

There is only one certainty in life on JZ's pole: his survival is your survival and the fact that you are on the pole is only because he is at the top.