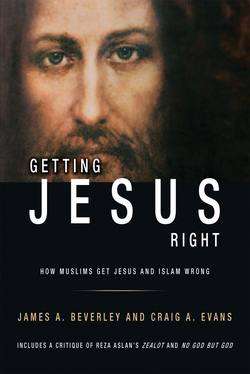

Читать книгу Getting Jesus Right: How Muslims Get Jesus and Islam Wrong - James A Beverley - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Jewish Monotheism

ОглавлениеThe major distinctive of the religion of ancient Israel was its commitment to monotheism, the belief in one God. The people of Israel did not always live up to that ideal, and without doubt many were henotheists (those who believe in one particular deity) as opposed to genuine monotheists (those who believe that there is only one God).3

In any event, Israelite monotheism was quite remarkable in light of the fact that, with rare exception, the ancient Near East was a polytheistic world. Most peoples worshipped many gods, even if one or two of their deities were held in especially high regard (such as Baal by the Philistines or Marduk by the Babylonians). The temptation faced by the ancient kings of Israel was to compromise their monotheistic faith by agreeing to treaties with other nations in which the gods of these nations would be respected, perhaps even worshipped. Sometimes this meant placing an image (or idol) of a foreign deity in the city of Jerusalem, perhaps in the temple sanctuary itself. It was against this sort of thing that the Old Testament prophets spoke so harshly, calling Israel a harlot for chasing after other lovers, as it were (e.g., Isa 1:21; Jer 3:1; Ezek 16:26).

In the aftermath of destruction and exile at the hands of the Babylonians (586 BC), the people of Israel had learned their lesson. The nation was now committed to the ancient command of Moses:

“Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD; and you shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. And these words which I command you this day shall be upon your heart; and you shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. And you shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. And you shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.” (Deut 6:4–9)

This is the famous passage known as the Shema’ (“Hear”). In Deuteronomy, the fifth and final book of Moses, in which the Law is given a second time (for the benefit of the generation of Israelites about to cross the Jordan River and enter the Promised Land), Israel is commanded to love the Lord their God. But even here it would be possible to hold to henotheism, loyally holding to only one God (Yahweh), but at the same time, at least in principle, acknowledging the existence of other gods.

It is against this possibility that Isaiah speaks, giving voice to the word of Yahweh:

“You are my witnesses,” says the LORD, “and my servant whom I have chosen, that you may know and believe me and understand that I am He. Before me no god was formed, nor shall there be any after me.” (Isa 43:10)

“Fear not, nor be afraid; have I not told you from of old and declared it? And you are my witnesses! Is there a God besides me? There is no Rock; I know not any.” (Isa 44:8)

These prophetic utterances give clear expression to what we would today call strict monotheism. Isaiah asserts that there simply is no other God than Yahweh (or “the LORD”). He and he alone is God. No god existed before Yahweh and no god will exist after him. There is no god besides Yahweh. Moses and the prophets were not only monotheists; they were Yahwists. That is to say, the God they believed in was Yahweh, the God of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The people of Israel are commanded to embrace monotheism and not merely henotheism.

Jewish monotheism only intensified in the struggle against Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Syrian Greek ruler who in 167 BC attempted to coerce the Jewish people into giving up their ancestral faith and embracing that of the Greeks. The attempt failed, resulting in an independent Jewish state and a deeply entrenched commitment to Yahweh as Israel’s only God. Those who suffered and died for their faith in Yahweh (the “Maccabean martyrs”) were regarded as heroes and exemplary models. Polytheism or belief in another god was simply not an option for anyone at the turn of the era who claimed to be a true Jew.

It has sometimes been suggested that Jews worshipped angelic figures, in addition to God. But the evidence does not support this proposal. Angels and various powers were shown great respect, perhaps even venerated on occasion, but there really is no evidence that Jews who were committed to their ancestral faith worshipped angels.4 Jews in the time of Jesus never offered sacrifices to an angel—only to God. Jewish mystics may have attempted, or even experienced, a form of soul-ascent, whereby they entered heaven and partook in angelic liturgies, but they did not worship angels. They, along with the angels, worshipped God.

The divinity of Jesus—however it arose in the thinking of the followers of Jesus—must be interpreted against the backdrop of Jewish monotheism, belief in one supreme, absolute God, maker of all things, to whom everyone is accountable. How belief in Jesus as “God in the flesh” arose in what in its first decades was predominantly Jewish is the big question we must ponder.