Читать книгу Iron Rage - James Axler - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

Оглавление“It looks pretty,” Ricky Morales said.

“Bad country,” Maggie Santiago replied. “Worse comin’.”

She was a small woman, with jaw-length brown hair that was held off her face by a headband. She had a slight build and was decidedly flat-chested. Ricky was sixteen and noticed that kind of thing.

He wiped sweat from his forehead. The approach of the Yazoo River to its confluence with the Sippi was unquestionably beautiful, with tall green grass to either side, crowned by the shattered ruins of what he was told was Vicksburg rising above it to the south, and the brown expanse of the great river itself ahead. The Yazoo rolled by the hull of the Mississippi Queen, brown and slightly greasy in the hot sun, which threw eye-stinging darts of morning light at the slow, slogging waves.

A great blue heron, with its beautiful gray-blue plumage shining in the sun and a crest of feathers sweeping back from its head, stalked majestically through the shallows of the northern bank. It was hard to believe the green reeds lining the flow, and the green heights to the left, harbored any kind of wickedness or ugliness.

“I don’t know,” Ricky said, holding up a toothed washer to the near-cloudless sky to squint through it, looking for lingering grit or crud. The slight machinist and mechanic was teaching him to disassemble the Queen’s bow winch. It was just the sort of thing the youth found fun. “It looks double-peaceful to me.”

Krysty Wroth, her flame-red hair tossed by the slow afternoon breeze—moving, in fact, rather more than the light wind could account for—joined the pair. She stood gazing out of the blunt round prow of the river tug with one boot up on the gunwales. Ricky tried hard not to stare at the tall, statuesque woman. As usual. She was one of his companions, and one of the most beautiful women he had ever seen. He had a crush on her, even though she was the lover of the group’s leader, the one-eyed Ryan Cawdor.

“It’s hard to imagine anything so beautiful could be so deadly,” Ricky told Maggie.

A sliding brown ridge appeared in the water near the wading heron. A pair of big, broad jaws burst through the surface in an explosion of spray. They snapped shut on the majestic bird. A savage shake, a roll, a wave, and the bird was gone beneath the water with nothing to show that it had ever been there, except for a heavy roll of greenish water slowly diminishing to become one with the flow, and a blue-gray feather swooping down to light delicately on the river and be carried away downstream.

Ricky jumped to his feet. “Whoa!”

“Hey,” Maggie snapped. “Mind the parts, kid! You kick them in the Yazoo, and I’ll kick you in right after.”

She referred to the components of the winch, which they had spread out on oiled canvas. Though she was only an assistant to the vessel’s chief engineer, Myron Conoyer—also known as husband to the captain of the Queen, Trace Conoyer, with whom he co-owned the boat—she took her task seriously. So did the rest of the crew who worked for the pair.

“What was that?”

Maggie glanced that way. Ricky hadn’t thought she’d noticed the commotion, but she had.

“Nile crocodile,” she said matter-of-factly. “These waters are lousy with them.”

She gave him a gap-toothed smile.

“One of the reasons this is a nasty stretch of river,” she said.

Ricky looked at Krysty. “Didn’t that bother you?” he asked. He was still freaked out about seeing the bird snatched below the lazy, deceptively innocuous water so precipitously, and he needed someone to validate him.

“What?” she said.

“The bird—the heron. A big old croc grabbing it just like that—that doesn’t bother you?”

Krysty shrugged. He tried to keep his eyes off the fascinating thing that did to the front of the plaid shirt she wore, and failed.

“It’s just the circle of life,” she said.

“What’s the problem, Ricky?” a voice asked from behind him. “We’re not getting paid to sightsee.”

He turned. There was no mistaking that voice.

“He was alarmed because a Nile croc took down a heron, right over there, Ryan,” Krysty said, as her man approached with the captain and her husband alongside.

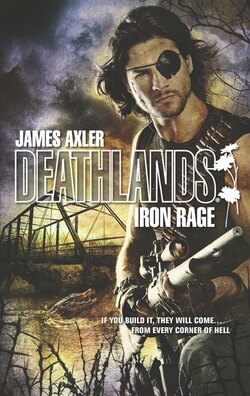

Ryan came up and put his arm around her. He was a tall rangy man, narrow-waisted and broad-chested, with shaggy black hair and a single pale blue eye. His other eye was covered by a black patch, and a scar ran from brow to jawline.

“I just don’t want him kicking any parts of my winch overboard,” Maggie said.

“Don’t worry,” Krysty told her. “He loves his machines far too much for that.”

“Nile crocodiles,” Ryan grunted. “Great.”

“Don’t mind them,” said the short, potbellied, curly-bearded man in the glasses next to him. He wore grease-stained tan coveralls. “Everything else here is much worse.”

“You and your exaggerations, Myron,” Trace Conoyer said. She was taller than her spouse, with a hawk nose and piercing dark eyes to match, and dark blond hair worn short. “Though for a fact, I’d just as soon people keep their eyes skinned proper until we’re well out in the Sippi stream and heading south.”

“Start with the worst thing, then,” Ryan said. “After that, it’ll only be good news.”

“Don’t be too sure of that, my friend,” Myron said. As the Queen’s chief engineer, he was Ricky’s nominal boss while aboard the vessel. Although in Ricky’s mind his boss would always be the group Armorer, and his mentor, J. B. Dix.

And Ryan, of course.

Most of them had abilities that were useful to the vessel and her crew—even Doc, with his weird, eclectic old-days knowledge.

As a general rule, Ryan Cawdor did not hire his group out for sec work, unless survival was at stake, for one reason or another. When survival for himself and his small, loyal band of friends was concerned, anything and everything were always on the table.

The companions had been hired on the Queen as crew. There was always plenty of work to be done. Captain Conoyer was grateful for fourteen extra hands to do it, and willing to pay with room and board and a share in the proceeds of every transaction—the same deal she and every other member of the crew had. With differences in percentage, of course.

One of the conditions of the companions’ employment was that if—more likely, when—there was fighting to be done, they would be required to defend the ship. It just so happened that the new crew members were all ace at that particular skill.

But then again, that was pretty much an unspoken condition of every job, including just living day to day. They lived in the Deathlands, after all.

“Stickies,” the captain said. “Been colonies of them around the confluence of the Yazoo and the Sippi for fifty years, the old river folk say.”

“Do they ever attack boats?” Ricky asked, as he settled back down by the tarp on which the winch parts rested.

“Not if they keep well clear of the banks,” Trace said.

“What if there are snags on the river?” Krysty asked. “Or mebbe sandbars narrowing the channel.”

“Like I said—if they keep clear of the banks. Otherwise all bets are off.”

“Don’t forget the rads,” Myron said helpfully.

“Rads?” Krysty and Ricky said almost simultaneously.

“Oh, I was getting there,” Trace stated. “Not just rads, but heavy-metal pollution, big-time. You know how you always hear talk about strontium swamps? Well, they actually got stretches of that around here.”

Ricky eyed a flock of ducks starting noisily from some reeds on the right bank. “Does that mean those birds are muties too, if they can live around here?”

Trace shrugged. “Many of the creatures seem less affected by the rads than we are,” Myron said.

“Sounds like a double-bad place for shore leave,” J.B. said, approaching from astern.

“It’s not my idea of a vacation spot,” added Mildred Wyeth, who walked by his side. She was taller than he by a slight margin, which the battered fedora he wore tended to disguise.

“The rads won’t kill you,” Myron said. “Not right away. The swampers who live in these bogs will likely get you first.”

“Swampies?” Mildred asked.

“Swampers,” the engineer repeated, with added emphasis on the second syllable. “Not muties. People.”

“Of a sort,” his wife told them.

“Wouldn’t they have to be muties to survive if the rad count’s that high?” Ricky asked.

“They’re too mean for the rads to chill,” Santiago offered.

“How about them?” Ryan asked. “Do they go after vessels that are underway?”

“Not much when they stay clear of the banks,” the captain said. “Like the stickies. Like most things, come to that. That’s another reason we stay out in the middle of the channel when we can. The river’s lethal enough. We don’t need the grief that comes from land.”

“Which is her typically sour way of saying the river is our home, and we feel safest here,” Myron said. “Right, my love?”

That got a lopsided grin from the captain. “Anything you say, Myron.”

Ricky picked up a sprocket and held it up to the sun to be examined.

“I get it,” he said glumly. “Everything’s dangerous. Especially everything beautiful.”

Ryan winked at Krysty and grinned. “Pretty much.”

“The real danger is the darkness in the human soul,” said Nataly Dobrynin, the Queen’s first mate, emerging from the superstructure and walking up to join the others. She was on the tall side, taller than either Conoyer, and skinny. She wore her long, dark brown hair pulled back in a ponytail that emphasized the austere bone structure of her face, and her slightly angled gray eyes. She never smiled, and intimidated the hell out of Ricky.

Surely that can’t be right, Ricky thought. Stickies are double dangerous, for one thing. Rads and heavy-metal poisoning, for another.

He looked to Ryan for confirmation. He sure as nuke wasn’t contradicting the somewhat-scary mate.

But Ryan frowned thoughtfully.

“That’s true enough,” he said. “That’s what blew up the world, after all.”

“Some would blame the cold hearts of the whitecoats, lover, never mind the darkness of their souls,” Krysty said drily.

“That ‘some’ being you.”

She grinned; he shrugged.

“Well, ‘some’ aren’t wrong,” he said. “But they still had their reasons, which fieldstripped down to that.”

“I’d say it was the madness of shutting themselves off from the natural world in order to try to control it,” the redhead said.

“Sounds like the same thing, to me,” Nataly said. She turned to Trace. “Captain, we’re coming eight up on the confluence.”

Trace nodded. “Right. Everybody, get to your stations. Break time’s over. The big river’s mood doesn’t look bad today, but wrestling this bitch of a barge through the turbulence where the streams join could get triple ugly triple fast.”

“You best put your toys away and step lively too, Ricky,” Ryan said. “I think we need to have weapons in hand when we hit the Sippi. With the captain’s permission, of course.”

“Why’s that?” Myron asked. The bespectacled engineer sounded more curious than challenging.

“Junctions are good places for bad things to happen,” J.B. stated, settling his fedora more firmly on his head. “Like crossroads. Reckon rivers aren’t any different.”

“They used to say the Devil hung out at crossroads,” Mildred said. “Back in the, uh, day.”

Ricky turned his face down to hide his grin. The “day” she meant was back in the long-dead twentieth century, where Mildred had lived most of her life. She had undergone a routine abdominal surgical procedure and something had gone wrong. She’d been frozen in a cryogenic procedure and shipped to a cryocenter in Minnesota just as the balloon was going up on the Big Nuke.

Trace nodded. “You’re right, Ryan. Take your people to full alert. But stand ready to lend a hand if it turns out the river’s what we really need to be worried about.”

Ryan nodded.

“Get that winch back together double quick,” Myron said, all business now.

“But we haven’t finished cleaning it,” Maggie protested.

“Yes, you have,” Myron told her, his tone at once gentle and commanding. “You’ll just take it apart again and clean it after we’re headed up the Sippi for Feliville.”

“Aye-aye, sir,” she said glumly. Then she sat back on her heels, looked at Ricky and suddenly grinned.

When she did that she was positively cute, he thought.

“All right, champ,” she said. “Show me what you’ve got.”

* * *

THE DECK ROLLED beneath Ryan’s boots as the Mississippi Queen chugged into the joining of the Yazoo with the Sippi.

His Steyr Scout Tactical longblaster in hand, he stood at the bow, with Krysty at his side. The rest of the companions were spread out around the eighty-foot-long vessel’s perimeter, interspersed with armed members of the Queen’s regular crew. Doc Tanner, his LeMat combination handblaster and shotgun at the ready, held a position to Krysty’s right. J.B. was to Ryan’s left, holding his Uzi, and Mildred flanked him farther astern. Jak Lauren, their young scout, stood in the stern. He was ready to run down the thick hawser by which they towed a hundred-foot barge stacked high with lumber and bales of cloth and leap aboard to repel any would-be boarders with his knives and .357 Magnum Colt Python revolver.

Finally, Ricky Morales, having reassembled the power-winch to his stern task-mistress’s approval, lay on his belly on the flat roof of the main cabin, ready to snipe with the DeLisle replica carbine he had helped his uncle make by hand, in happier times on his home island of Puerto Rico. Although it couldn’t really be called “sniping,” since the weapon lacked a scope, the boy could consistently hit his mark with whisper-quiet shots out to a hundred yards.

In the event Ryan’s people had to reach out and touch somebody—as Mildred put it in her quaintly anachronistic freezie way—any farther than one hundred yards, Ryan’s Steyr, which did have a scope, could do the job.

Not that Captain Conoyer believed there’d be any trouble. But she hadn’t batted an eyelash when Ryan suggested turning out as many hands with blasters as possible to wait for it, just in case. Having hired him in part as a sec consultant, as she put it, she had the sense to listen to him on the subject.

Over a third as wide across the beam as she was long, the tug was surprisingly stable as she chugged confidently out into the crosscurrent from the Sippi. As ballast she carried tons of big metal scrap chunks, plus crates of weapons and ammo that were the actual prizes from this current voyage up the Yazoo. The cream of the crop was a Lahti Model L-39: a bolt-action antitank rifle firing 20 mm armor-piercing rounds, in cherry condition, consigned to a wealthy baron up the big river. Or so Ryan was told; sadly, Captain Trace had refused to open the crate despite the near-drooling entreaties of J.B. and his apprentice armorer, Ricky.

The Queen began its turn to starboard almost as soon as it cleared the banks to the north. Ryan glanced back over his right shoulder, along the vessel’s length toward the barge. He knew that getting it safely around the corner would be the trickiest part. But Trace had taken the helm herself, and just in their brief time aboard Ryan and his friends had learned she was expert in piloting the boat.

The one-eyed man was just as glad the Queen wasn’t a pusher-style Sippi tug, of the sort her crew told Ryan had dominated the river before the nukeday. Bigger and of all-steel construction, they used to push not just single barges, but sometimes two or more in series—each many times larger than the wooden one the Queen was dragging toward Feliville—with their square prows. He didn’t even want to try to imagine how pulling off a maneuver like this would have worked in such an arrangement.

He was unlikely to find out. Nukeday had triggered colossal earthquakes that had started shaking up the continental US even before the warheads stopped detonating. None was worse than the quake caused by the New Madrid Fault Line that ran by the Sippi from north of Memphis to St. Louis. The blasts, quakes and seismic water surges had smashed most of the vessels on the river into twisted junk, left them high and dry when the great river actually changed channels, and even tossed them inland, sometimes even into the hearts of major cities.

They had become mother lodes of fabulous scrap for generations of especially intrepid scavvies. Or for barons willing to enslave the people of the villes they ruled to the arduous and dangerous work of ship-breaking. These days most of the river traffic was wood-hulled, driven by steam engines or, as the Queen was, by scavvied Diesels. And when they hauled barges they were content to pull them.

As Ryan turned his face forward again, he scanned the seven-foot weeds that obscured the Yazoo’s north bank and the east bank of the Sippi. He wasn’t sure what he expected to see, but he expected to see something. His gut told him that trouble was coming.

But it gave him not the slightest clue as to what that trouble would actually be. Nor where it would come from.

He looked back out across the Sippi and saw a geyser of water shoot up into the air, fifty yards ahead and a little off the port bow of the turning tugboat. A heavy boom hit him with an impact as much felt as heard. It was a sound he was all too familiar with.

He spun to look south. Steaming up the river from the south came four boats, a quarter mile away and closing slowly. They were a ragged assortment, no two alike, and none as large as the Queen herself. They had a strange, ugly, bruised glint to them in the afternoon sun, and were gray mottled with red. Black plumes billowed from their smokestacks and were swept away east by a crossing breeze.

Yellow light flared from the bows of the nearest two, accompanied by giant puffs of dirty-white smoke.

“Red alert!” he turned and shouted toward the Queen’s cabin. “Cannon fire! We’re under attack!”