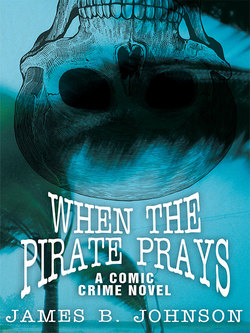

Читать книгу When the Pirate Prays - James B. Johnson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1: MONDAY, 6:30 A.M.

He wasn’t a bad fellow—even if he was out jogging. We picked him up at the old Port Boca Grande Lighthouse on account of the storm squalls boiling off the Gulf of Mexico. I didn’t recognize him then because of his four-day growth of beard and the fact he was wetter than a guppy on bath day.

“Another storm without a name,” he said, not even breathing hard after running against the wind and rain. His black hair was pasted back in a cinematic over-done fashion.

The three of us in the cab of my green ’66 Chevy pickup steamed the windows and, along with the now-lashing rain outside, made it difficult to see where I was driving.

I double-clutched down to second and left it there hoping it was only my imagination that the Gulf was looping over the dunes and onto the road already. Here at the southern tip of the island was where the pirate José Gaspar, in a fit of murderous rage a couple of hundred years ago, beheaded a princess. The mental image made me shiver, for I superimposed the vision of this intriguing good-looking woman with different color eyes back at the hotel. I love a pony tail anyway, and this intriguing woman, she had a pony tail I’d kill for. Not only that, but she smelled good and, something I didn’t understand yet, she had a case of the hiccups you wouldn’t believe. Her name was Mary Lynn.

Tapes sat in the middle, his long Texas legs jammed into his chest from straddling the hump. “This ain’t the most fun I’ve had in a long time.”

“Me, neither,” I said. I’d just had to see the lighthouse one more time before we left. It is my intention to visit every lighthouse in America before I die—and Canada, too, if I should live that long. We have upward of 440 or 450, including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. And there are a couple of lighthouses on St. Paul Island and the Main-à-Dieu Light on Scatari Island, Nova Scotia I’ve been looking forward to visiting. I couldn’t figure out where Gaspar buried the headless woman. It’s said her ghost at times wanders the beach looking for her head. Ugh. I looked, but never saw her—probably too windy.

I had the Chevy GT’s wipers on max. Wind and rain buffeted the truck rudely. The green truck was long past truck social security age but performed like it was forty years younger. We were now driving north on Gulf Boulevard.

The jogger leaned forward. He wore running shoes and blue shorts and orange shirt which had THE SKY IS BLUE AND THE SUN IS ORANGE SO GOD MUST BE A GATOR written on it, referring to the University of Florida Gators and their colors. In addition to the scrubby face, he had thick dark eyebrows and a wide cutting jawline.

“There’s something familiar about this guy,” I told Tapes, straining to think.

A strong gust blew my GT onto the shoulder of the road, and likely sand-blasted the left side.

We’d been on the very southernmost tip of Gasparilla Island for one last look at the lighthouse, wanting to see it at sunrise. Unfortunately, the storm had generated overnight and squalls had blown in right after we got to the Old Port Boca Grande Lighthouse. Now we were heading back to the JG Inn to have breakfast, pack our stuff, and leave. I wanted to return to the mainland, head south and see the Sanibel Island Lighthouse. The jogger had made the same mistake we had and we offered him a ride back to the tiny town.

“There is something familiar about me,” said the jogger with a disarming smile.

“I told you so,” I said. “Is this twenty questions?” When I’m out of sorts, I tend to have a sharp tongue. Right now I didn’t need to split my attention between driving in the storm and verbal sparring.

“Look, Shortcut, if he wants us to know who he is he’ll tell us.” Tapes took out his tin of Copenhagen, shook his head, and returned it to his pocket. He was trying to quit. He’s got a great deal of willpower and likely would succeed. On the other hand, maybe Tapes was in fact human and having a difficult time weaning himself from nicotine.

We passed the Rear Range Lighthouse, a straight metal cylinder with a lattice-work of struts and supports. The Old Port Boca Grande Lighthouse is a wooden structure like an old Southern home, with wraparound porches on three sides of the first level. The next level up was like a crow’s nest, a pudgy neck to the building before you get to the top level. Which is the light itself, a third order Fresnel lens, surrounded by a wooden catwalk. It was three-and-a-half power with a red flash every twenty seconds. I’d timed it. The whole thing rested on pilings so that wind and water could pass through. It was one of the thirty formal and official lighthouses in Florida. When we finished seeing them, we were going to return to Arizona where I needed a job, having just quit mine in disgust, and Tapes already had a job mothballing aircraft in Tucson, passing, of course, through God’s Country, otherwise known as Texas, our birthplace and frequent home. My job had been in Tallahassee and when Becky and I broke up—

“Got it,” I said.

“Windmills or lighthouses?” Tapes asked rhetorically.

We argued about damn near everything. This particular ongoing argument was whether windmills were more aesthetic than lighthouses. I liked lighthouses better than windmills. Tapes preferred windmills. ’Course, lighthouses always had the best locations and scenery.

“Neither,” I said. “He is familiar.” I hooked my thumb toward the jogger. His approximate age, forty-five, finally led me to it.

“Well?” Tapes demanded.

“Henry Beauchamps Gonzáles,” I said smugly.

Tapes scratched his head which was brushing the roof of the cab. “Name’s familiar.”

“You’re from Texas and Arizona and don’t need to know Florida stuff,” I said. “The beard and drowned hair disguised him. Besides, people don’t look the same in person as they do on television on the news.”

Gonzáles looked like he wanted to pull his hair out we were taking so long to acknowledge him. A little vanity never hurt nobody.

“The Democrat Governor of Florida,” Tapes said.

Gonzáles nodded emphatically.

“How come you’re out jogging alone?” I asked, keeping my voice neutral, for running wasn’t anything I was near fond of. Neither was Tapes.

“This island is my home. I own the José Gaspar Inn. I live there, too. I jog every morning and my assigned Florida Highway Patrol trooper feels it’s safe enough before dawn.”

There it was again. Everything around here named for the nasty hombre himself. José Gaspar had kidnapped, imprisoned, raped women all along this coast, not to mention your basic pillaging and plundering. Say 1873, until he killed himself twenty-six years later.

Since then, Gaspar’s become a local legend, time being kind to him as to other killers such as Billy the Kid. Just south of Gasparilla Island stretches Captiva Island, a key where Gaspar kept his kidnapped women. He had captured the Spanish princess and she spurned him, and spit in his face. That’s why he whacked off her head.

The Gulf coast of the island was perhaps fifty yards to the west and I saw no ghosts, headless or not. The wind was now blowing with serious intent and pushing big rollers ahead of it over the dunes, through the brush, and onto the roadway. A dog-sized wad of Gulf froth slapped the windshield and slewed off like spit in the wind.

“Many years ago,” the governor said, “maybe in the early eighties, in Sarasota just north of here—”

“I know geography, we drove through there,” I said and immediately regretted my short-tempered interruption. I’m vain about geography.

“You have to forgive him,” Tapes said, “he just broke up with—”

“You leave Rebecca out of this—”

“Becky,” Tapes corrected, nodding earnestly, “and he ain’t his real self nowadays. Jeez. You got to be especially sensitive around him—”

“The governor doesn’t need to know about my nonexistent love life,” I said testily.

Gonzáles was glancing between us, looking like he just swallowed a handful of chili powder.

I stared at him expectantly, one eye on the road disappearing in and out of the wipers. “Well?”

“Well what?”

“The Sarasota no-name storm,” I prompted.

“Oh, yes. It caused more damage than any named storm or hurricane in a long time.” He scratched his incipient beard. “It dissipated rapidly.”

I grinned at Tapes. “‘Dissipated rapidly’?”

“Now you done it,” Tapes accused Gonzáles with a frown.

“Done what? I mean, did what?”

“Shortcut will use it to death. Everything now will dissipate rapidly. Dinner, clouds—”

“Beer,” I added.

“You’re Shortcut?” asked the governor.

“You’ve heard of me?” I asked.

“Not at all,” said Gonzáles with a twinkle in his voice. Right then, I liked him; he was giving it back to me in kind and, hell, I deserved it. Damn Rebecca—Becky, rather—for putting me in such sour circumstance.

How was I to know Governor Henry Beauchamps Gonzáles would be dead in less than ten minutes? And right after I decided I liked him, him being a politician and all.

“You drive very well,” Gonzáles told me.

“Thanks.” I avoided an ocean by driving on the shoulder of the road I couldn’t see and through a flower bed. The salt water coming up from the Gulf would kill all the flowers anyway. “Like Alcibiades in a chariot race.” It hadn’t been my intention to bring that up, but it just slipped out, my mind being occupied with concentrating on driving and all.

“Who?” asked Gonzáles.

I’d never talked to anybody who knew how to pronounce Alcibiades’ name, so I was guessing. Of course, I ain’t in the classics social circles.

“Alcibiades,” I said, and Tapes groaned. I pronounced it like “Al-kye-bye-aye-dees.” I shrugged mentally. What the hell. I’d never been out to impress people anyway. On the other hand, I hated to make a jerk out of myself. “One of the guys Plutarch wrote about.”

“Ah, the traitor,” said Gonzáles. “He betrayed Athens in favor of the Spartans and ruined democracy.”

“He got a bum rap,” I said. “You ever read what Plutarch says about that?”

“Gimme a break,” said Tapes.

Wrenching the steering wheel to the side to compensate for a strong gust, not to mention not being able to see, I thought about paybacks to Tapes. “Once, Alcibiades entered seven teams in the Olympics. One account has it that he won first, second, and fourth; Euripides disagreed, reporting Alcibiades came in third and that was it. Have I ever told you that, Tapes?” I was not needling him, just reminding him of my idiosyncrasies.

“A hundred times, Shortcut. And you never pronounce his name the same.”

“Well, here’s one I haven’t told you. A. J. Foyt said, ‘Every year I get older and go faster. It’s a helluva deal.’ A. J. must’ve been talking about me.” I looked around Tapes to the governor. “A. J.’s from Texas, too.”

“Who are you people?” asked the governor. “You talk like cowboys, yet you quote Plutarch. You dress like cowboys and drive a forty-eleven-year-old truck.”

“I’m Shortcut. He’s Tapes.”

“Nicknames,” said the governor. “Do you have a real name you answer to?”

“I don’t give that out freely.”

“He doesn’t tell strangers,” Tapes said simultaneously, always protective of my fragile ego.

Gonzáles stiffened.

We’d abused our newly found friendship. I waved my hand in a disarming manner and suddenly the truck slewed and banged into something I couldn’t see. I grabbed the wheel like an astronaut cut loose from the space shuttle. “I’m Billy Birthday and this is Wallace Francis Fidgle.” Tapes was born with the bark on. He was wearing a pullover shirt upon which burgeoned a mushroom cloud over which appeared the words “MADE IN AMERICA,” and under the A-bomb explosion were the words “JUST TRY US.” Very tacky.

Gonzáles nodded approvingly. “What are Plutarch-quoting cowboys doing on Gasparilla Island, Florida?”

“Vacationing and checking out lighthouses,” I said. Generally, Tapes lets me do the talking for both of us. He’s usually very quiet: unlike me, if he doesn’t have anything to say, he doesn’t say it.

“It figgers,” said Gonzáles like he knew he wasn’t going to get a straight answer. “You have a way with words.”

“He says he’s as eloquent as Cicero,” said Tapes, surprising me. We hadn’t seen each other for a few months and he wasn’t used to not talking yet.

“I got a GED,” I said.

Have you ever seen a lighthouse lonely against dark seas and skies? Standing on a spit of sand or stone, lancing oceans and seas, gutting clouds, slicing fog? A majestic version of human engineering, a bastion against the absolute worst nature throws? Were lighthouses music, grown men would cry more frequently.

“Turn right,” Gonzáles directed, indicating with his right pointy finger.

Perceptively, the wind decreased. We drove down a lane lined with giant banyan trees along both sides. The resultant canopy made it even darker. The wind funneled through from behind us, west to east, and scooted my truck along faster.

“Where we going?” I asked.

“The Inn. Surely the bridge will be closed. Might even wash out.”

“We haven’t checked out yet.” The way it looked, we’d be here a few more days.

The governor’s face scrunched up as he stared at banyan limbs whipping about us. “I grew up on the island, and I’ve never seen a storm come on so quickly.” He rubbed a misted spot off the side window. “If that high pressure system is stalled just to the north of us, this storm will sit here for a while.”

“Meteorology comes naturally to some people,” I said, making my smile disarming. “Too bad talking about the weather’s become a cliché.”

“Not at all,” he said. “I listen to NOAA weather radio every morning.”

A flying object shot into my line of sight, just for a second at the end of a wiper arc, and I braced against the seat.

The truck shook and we heard the metallic clang even over the storm sounds. I held the wheel hard, trying not to overcompensate and worrying about the new metallic green paint-job.

Tapes leaned forward. “Left front quarter-panel.”

The GT was driving without malfunction. “Damn. I hate body work.”

Tapes gave me that look.

“Okay, okay.” I shook my head. Tapes usually fixed body damage and I worked on the engine and accessories.

Gonzáles directed us left and right and a couple turns I wasn’t altogether sure about, and there was the José Gaspar Inn. I recalled that in addition to being a lawyer, he had family money. I guess the grand old hotel was part of that.

I drove through the turnaround under the flapping canopy and we dropped him off.

“Thanks,” he said without any sense of closure.

We went and parked the truck, selecting what I thought would be a safe location. Knowing Gonzáles owed us for the ride, I didn’t mind driving over his lawn and parking on the lee side of the big, sprawling inn. The GT nestled alongside the east wing up against a giant gardenia bush which was whipping around like a gutted snake.

Something had hit the roof and ripped the CB antenna off. The CB was inop anyway, and I hadn’t fixed it since modern cell phones came upon the scene.

With a minimum amount of guilt, I hoped that intriguing woman named Mary Lynn was stuck here, too. Tapes says I fall in love at the drop of a hat. But the fact is I’m seldom attracted at first sight. And once I was old enough to figure life out, I’ve tried not to let the fact that a woman is very attractive sway me to favor her. Sure. But this woman’s high forehead and arched eyebrows spoke of quick intelligence. Her two-color piercing eyes got my attention like a red flag to El Toro Diablo and her legs made my gut contract like a tropical disease. Then the specter of Rebecca in Tallahassee cast a great shadow over the cold, desolate land that was my love life.

Henry Beauchamps Gonzáles was probably dead before we reached the side door.

Tapes retrieved his twenty-five-foot Lufkin Unilok tape measure from the glove compartment and, battling the increasing wind, I got our wet weather gear from the cross-body Trukbox in the pickup’s bed. I believe in the Boy Scout motto or, more specifically, the Seven P Principle: Proper Prior Planning Prevents Piss Poor Performance.

It didn’t help the governor a bit.