Читать книгу Peyote Wolf - James C. Wilson - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

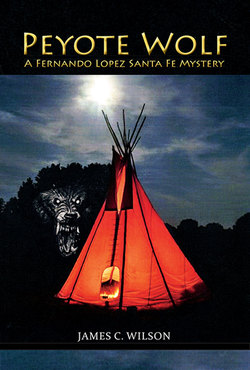

ОглавлениеPeyote Wolf

A Fernando Lopez Santa Fe Mystery

James C. Wilson

Dedicated to Cindy and Sam, my wolf pack.

Preface

I came of age reading the detective novels of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. I loved how these stories evoked a sense of place, especially Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles. Chandler’s The Long Goodbye is still one of my favorite novels. I also loved how these novels could reveal the fractures in the societies they represented: that is, the cultural, ethnic, and class conflicts that divided people.

Living in Santa Fe during the 1970s provided me with much the same material and inspiration. During that turbulent decade the entrenched Hispanic social and political fabric of the city came under siege by an influx of wealthy Anglos from the East and West coasts and from a wide variety of activists and revolutionaries demanding change and seeking power. Among these groups were La Raza and Native American activists and the counterculture movement personified by Dennis Hopper and his followers who invaded Northern New Mexico. I sometimes refer to this decade as the “fighting seventies.”

Peyote Wolf, the first of my Fernando Lopez Santa Fe mysteries, attempts to expose some of the social fractures that still exist in Santa Fe while telling a whopper of a tale.

The Peyote Ceremony

Michael Soto took the bag of peyote from Cedar Chief. He chewed one brown button and passed the bag to the next person in the circle, a woman whose face was partly concealed by a red shawl. Road Chief sat in the rear of the teepee leading the ceremony with his eagle-bone whistle and bag of sage. Taking them down Peyote Road.

The fire provided the only light in the teepee. Fire Chief poked and prodded the coals, then tossed another piñon stick on the fire. He watched the smoke drift up to the open flap in the top of the teepee and dissolve into the blackness. Beyond the opening he could see a patch of night sky, the stars framed by the ends of the teepee poles. As the fire hissed and snapped, the woman beside him began to moan and rock from side to side. Diagonally across the teepee, an Indian boy sitting next to Fire Chief slumped back against the canvas with his eyes closed. The young man from San Ildefonso Pueblo might prove a useful connection in the future.

Road Chief stood, a tall ungainly man with red hair and a handlebar mustache. When Road Chief blew his whistle and began to sing, Drummer Chief joined in, shaking his rattle and beating the ceremonial drum slowly at first, then faster.

It was then he noticed that Road Chief’s wife, who served as Peyote Woman, wasn’t singing. Instead, she was staring directly at him. Did she know he was only pretending to sing along?

Suddenly he felt nauseous, the peyote beginning to take effect. With his eyes closed, he lost all sense of time. His mind skipped over certain moments, then stuck on others. He heard singing and drumming and talking and the constant background noise of the fire crackling and the bodies shifting on the sand. He didn’t open his eyes until he felt someone touch his left arm, an excruciating sensation. Trying to focus, he saw Cedar Chief passing a small bag of sage. He took a pinch of the dusty green leaves and rubbed it on his arms. He felt another wave of nausea swell in the pit of his stomach.

The attacks of nausea were what he hated most about the ceremonies, but somehow he always managed to suffer through them. Truth was, the peyote meetings were essential to business. Many of the tribal objects he sold in his Santa Fe gallery came from the locals he met at the meetings. So he doubled over and waited for the feeling to pass.

Gradually his perception shifted. He sensed movement around him, gradually becoming aware of the silence in the teepee. How long since the singing had stopped? He decided it must be midnight, time for the ceremony known as the Midnight Water Call.

Confirming this, Fire Chief got to his feet, stretched his legs, and followed Peyote Woman outside to get the pail of water used in the ritual. By now he knew the routine well enough.

Road Chief would sing a song of purification, followed by prayers from the other three officials. Next, water would be poured on the ground, the drum, and the altar. Only then would the holy water be passed around the circle for them to sip. They were supposed to take just enough to ease their dry throats, but he always took more. The next chance to get a drink would be at sunrise during the Morning Water Ceremony that concluded the official part of the meeting.

While they waited, they heard unexpected footsteps approaching the teepee, followed by a loud, angry voice. Had an intruder come to disrupt the meeting? Before any of them had time to react, Fire Chief came stumbling through the opening in the teepee and fell on top of his pail, spilling water on the fire. Steam hissed from the wet coals.

“What is it?” Road Chief glanced angrily from Fire Chief to the open canvas flap.

Suddenly a man with the head of a wolf stepped out of the darkness into the teepee.

Cedar Chief screamed at the sight of the wolf mask, with its rows of white teeth, its red tongue and snarling mouth.

The wolfman scanned the frightened faces, his small dark eyes peering out of twin openings in the mask, then raised his arm and pointed a long bony finger directly at him.

For a moment he felt paralyzed by fear. The mask looked like the head of a real wolf. Instinctively, he grabbed a handful of sand and tossed it at the intruder’s eyes. Then he jumped to his feet and pushed past the wolfman outside where he stumbled into the woodpile and fell heavily to his knees. A burst of adrenaline gave him energy and cleared his mind. Ignoring the pain in his legs, he struggled to his feet and took off running across the desert. His car was parked about a hundred yards away, over near José Padilla’s house. The shortest route would take him across a flat, open stretch of chamisa and piñon. That wouldn’t do, too much visibility there.

Instead, he ran toward the deep arroyo offering protection that circled around behind Padilla’s house. He could walk along the sandy bottom out of sight until he came to within twenty or thirty yards from his car. When he was sure the coast was clear, he could make a dash for it and get out of this place, Jacoñita. Away from the man with the wolf mask, whoever he was.

Finding the arroyo turned out to be easier than he expected once his eyes adjusted to the light of the half moon. He plunged down the steep bank and fell forward, sprawling on the cool sand. He paused a few moments to listen for the wolfman. Not a sound, so he scrambled to his feet and crept along the soft floor of the arroyo, being careful to avoid rocks. Several minutes later he took a look around, then climbed to the top of the arroyo and glanced back toward the teepee.

What he saw startled him. The fire inside the teepee illuminated the translucent white canvas from within, creating an eerie lantern effect. He could see shadows of the people inside, silhouetted against the glowing white canvas. The sight puzzled him. Why had the others stayed in the teepee? Where had the wolfman gone?

Something seemed wrong. He wondered if he was being double-crossed. Maybe Road Chief wanted the business all to himself. The bastard. He’d never trusted Reno. Not wanting to waste any more time, he walked faster, hurrying to get to his car. To the east he could see the distant lights of Santa Fe about twenty miles away. Much closer loomed the imposing mass of Black Mesa.

When the arroyo turned south, he knew he was getting close to where he needed to be. Close enough. He clawed his way up the crumbling bank and looked over the top at Padilla’s house. Moonlight reflected off the dark windows and the pitched tin roof of the old adobe. He saw the square shape of Road Chief’s van parked in the gravel lot beside the house. Then his black Porsche, no more than a hundred feet away, just beyond a patch of chamisa. An easy run.

He pulled himself out of the arroyo and, crouching low, moved out into the open. Moonlight and shadow, with strange noises everywhere. He heard the sound of small animals, probably lizards, scurrying under the bushes. From over near Black Mesa came a plaintive howl—a lone coyote.

His footsteps grew louder as he picked up speed. Finally he didn’t care. He ran the last few yards, crashing through a tangle of chamisa, the branches ripping his shirt and scratching his bare arms. When he opened the door and dropped into the driver’s seat, he found himself gasping for air. But he didn’t stop to get his breath. He slammed the door and started the engine. Then he reached for the gearshift.

“Turn off the engine,” came a deep voice from the back seat.

He gasped, his hand freezing in mid-air. In the rearview mirror was the face of a wolf.

There was just enough light to see white fangs and a red tongue hanging obscenely from the snarling, ghastly mask.

Part One: Fernando Lopez

1

Detective Fernando Lopez wished he’d had more time to put on his game face this morning. He didn’t wake up so easily these days, not without his two cups of coffee. Age had begun to drain his energy and stiffen his joints. Hardly fitting for a patriarch, a man of honor from one of Santa Fe’s oldest families.

He opened his 7-Eleven bag and took out the cup of steaming black coffee. He fumbled with the soggy containers of cream and sugar, dumped a little of each into cup and stirred the mixture with a No. 2 pencil courtesy of the Santa Fe Police Department. The taste of freshly brewed coffee jolted his senses. What he really needed this morning was a cigarette, but since he had quit smoking, more or less, he would have to make due with only coffee. He still kept an open pack of Camel Lights with him at all times, just to remind himself that he had the willpower to stop. And in case of an emergency.

From experience he knew he would be totally out of sorts until he had ingested the right amount of caffeine. He always seemed to be in a bad mood first thing Monday morning, but he was in an especially bad mood today because these two Indians were waiting for him when he walked into his office at half past eight. He hated not having time to put on his game face before all the people with problems began arriving.

He crumpled the 7-Eleven bag and tossed it on his desk with the Sonic Drive-In cups and the Great Burrito Company wrappers.

He took a sip of coffee. “What pueblo did you say you were from?”

“Zuni,” replied the older man who’d introduced himself as Robert Naranjo and his friend as Billy Suino. He had a big belly and long black braids.

He frowned. He didn’t see many Zunis. The Zuni Pueblo bordered Arizona, two hundred miles southwest of Santa Fe. Zunis usually took their problems to the Tribal Police or to the Gallup Police.

“We came to you because of this.” The younger man took a folded piece of paper out of his shirt pocket and handed it to Fernando. He was wearing a Los Angeles Dodgers baseball cap pulled down over his forehead and a Nike T-shirt. He looked like the athletic type, slender and muscular, maybe a long distance runner.

He unfolded the paper which turned out to be a short letter addressed to the Zuni Tribal Council. The letter read: “If you want your ahayu:da back, go see Michael Soto, the owner of Sabado Indian Arts gallery in Santa Fe. Soto is trying to sell the ahayu:da around town for $50,000.” The letter was signed: “A friend.”

He read the letter again. It was typed. Cheap paper. Anonymous.

“Would you care to explain?”

The younger man looked angry. “Explain what? We want our ahayu:da back. That’s why we’re here.”

He pronounced the Zuni word: ah – ha – yoo – dah.

Then Suino folded his arms across his chest, as though demanding immediate satisfaction. Wouldn’t it be nice if things were that simple?

Sighing, he glanced at the ugly brown wall behind Suino, surveying his many plaques and awards from the Hispano Chamber of Commerce and the Fraternal Order of Police. His eyes came to rest on his citation framed in silver from the governor of New Mexico commemorating thirty long years of distinguished service to the city of Santa Fe.

Indians made him nervous, even after all these years as a cop. He preferred the term “Indians” to the politically correct “Native Americans.” The fact that his ancestors had intermarried with both Indians and Anglos didn’t make much difference. He couldn’t help feeling they held him personally responsible for the Spanish conquest of New Mexico. The Spanish referred to it as the “Colonization,” but the Indians called it theft, beginning with Coronado in 1540 and culminating in the government of Don Juan de Oñate, the first official governor of the province known as “Nuevo Mexico.” Over four hundred years had passed since Oñate arrived in 1598, but the Indians hadn’t forgotten. Nor had they forgiven.

That was the problem with Santa Fe—too much history. People still held grudges about events that happened hundreds of years ago. Take Don Diego de Vargas and the Reconquest of New Mexico in 1692, twelve years after the northern pueblos had united forces and driven the Spanish settlers, soldiers, and priests, south to El Paso. The Pueblo Indians hated de Vargas and resented the Reconquest as much as or more than the original Colonization.

Was de Vargas a savior or a mass murderer? The answer depended on your point of view. Four hundred years hadn’t eased tensions one bit. And the arrival of the Anglos in the 1800s had just added another layer of grudges.

“I’m sorry, but what’s an ahayu:da?” he asked, hating to admit his ignorance. He wondered what Suino really wanted back. His land? The last four hundred years?

“A sacred war god. One of them was stolen this summer.”

He squinted over the top of his coffee cup. “When you say ‘sacred war god’, what exactly do you mean? An object? A person? A spirit?”

Suino looked offended. He sat erect in the chair, his head held high. He was young and handsome with a long, thin nose and high cheekbones. “No, a carved wooden figure. A sacred carved wooden figure.”

“So then, we’re talking about an object,” he said, reaching for a notepad.

Suino shrugged, not acknowledging his distinction.

“Here, take a look,” the older man said, taking a cell phone out of his back pocket and showing him a photo. “See, our Deer and Bear Clans carve the ahayu:da,” he added, nodding his head, trying to ease the tension between him and Suino. “We place them in sacred shrines on Zuni land. You know, leave them out in the open until they disintegrate. Because when they disintegrate, they replenish the earth.”

He wrote all this down on a legal pad.

Naranjo continued. “Problem is, the ahayu:da can be mischievous gods. They cause mischief if removed and not returned to their rightful places on the reservation.”

“What kind of mischief?”

“Natural disasters, mostly. Earthquakes and floods. Like that.”

He frowned. “Natural disasters?”

Naranjo nodded. “Unless returned to their shrines.”

“You said someone stole an ahayu:da this summer. Do you have any idea who?’

“Could be anybody.” Naranjo shook his round, weathered face. “An art dealer...a grave-robber...one of the hippies who come to hike on our land without asking permission. We see them all the time. We tell them to leave, but they just come back.”

“Even a Zuni,” Suino added. “One who’s become greedy like an Anglo. Or a Mexican.”

He knew Indians commonly referred to Hispanics as Mexicans, but common or not, he didn’t like to be called a Mexican. Nor did he like this Suino fellow. Still, he had a job to do, so he tried to put aside his feelings and assume an air of polite informality. “Can these carvings be sold for as much as fifty thousand dollars?”

Suino shrugged. “How would we know, we don’t sell our own ahayu:da.”

He scratched his head. “Okay. Why don’t you give me a description of the missing ahayu:da.”

Suino corrected him. “Stolen.”

He started to respond, then thought twice about it and took a drink of coffee instead.

Again Naranjo intervened. “It’s slender, about thirty inches long, with a face carved in the wood.”

He recorded the information. Then he passed the notepad to Naranjo. “Write down a phone number where I can reach you. Are you staying in town?”

“We thought maybe you could get the ahayu:da back today,” Naranjo said.

He shook his head in disbelief. They didn’t expect much, did they? “That depends. I’ll talk to Soto, but I can’t promise anything. For all I know, he might have already sold the ahayu:da. Or the letter might be a hoax. I’ll get in touch with you as soon as I can.”

“Then we’ll stay in town,” Suino said.

He didn’t like the way Suino said that. It sounded like a threat. “Suit yourself.”

Suino sprang to his feet and pulled the baseball cap lower on his forehead. Naranjo nodded, sighing as he got to his feet. He gave him an apologetic look, and then turned and followed his young companion into the dimly lit corridor outside his office.

Relieved to be alone, he settled back in his chair to relax. His mind began to clear, a process that seemed to take longer the older he got. Lately he’d been thinking about retiring. His wife wanted him to. His daughters, too.

They’d also convinced him to stop smoking. He finally gave in to their complaints and surprised them this past spring. They didn’t know he still carried around his emergency pack of Camel Lights. What had his wife said last night? Something about his face being as wrinkled as a saguaro cactus. She blamed smoking for all his troubles, including the wrinkles, but he wasn’t so sure.

Who wouldn’t have wrinkles after thirty years of police work? Too many people with bad attitudes. That was a fact.

He didn’t look forward to questioning Soto. Rich gallery owners were some of his least favorite people. He didn’t know much about Soto, just that he’d bought Sabado Indian Arts on the Plaza. He’d seen Soto only once, at some function at City Hall. He couldn’t remember the occasion, but he did remember the small man in the linen suit, very outgoing, a natural salesman. With his short black hair slicked back, Soto looked like a gigolo from a 1930s Hollywood movie. Hard to forget.

He took the opportunity to step outside for a breath of fresh air, just to clear his head. When he returned, he decided he needed another cup of coffee before making any decisions about how to proceed with this ahayu:da business, so he went down the hall to the coffee machine. He didn’t like to drink coffee that came from a concession machine, but at the moment he didn’t want to walk down the street to the Great Burrito Company.

From the hallway he spotted Fidel Rodriguez talking to the police dispatcher at the front counter. Sure as the sun rose every morning, Fidel or one of the other metro reporters from the Santa Fe Independent would show up at the station about eight o’clock to read the police log for the latest criminal activity in the area. They loved the juicy stories, the murder and mayhem stuff. Fidel was one of the few reporters he admired because Fidel didn’t sensationalize.

Fidel had manners. That was more than he could say for most of the hotshots who worked for the Independent.

“Fidel.” He held up his cup.

“Are you buying?” Fidel, a small dapper man wearing a blue work shirt and red paisley tie, minus the jacket, asked.

“Sure, if you can drink this shit,” he grumbled.

Fidel stuffed a notebook in his back pocket and stepped behind the counter.

He inserted more quarters in the coffee machine and handed Fidel a small paper cup filled with murky black liquid. “Santa Fe Concessions.” He shook his head. “I think they’re trying to poison us.”

“Doing a pretty good job, too. You look like hell.”

“Yeah, that’s what my wife says. She tells me I’m smoking too much.”

“I thought you quit.”

“I did, sort of.”

Fidel laughed. “So what do you have for me this morning? Any road kill last night?”

“Road kill? I hate that expression.”

“Sorry, cabrón. Just a little humor.”

While they talked, the police dispatcher answered a telephone call at the front desk. Linda Stephens jotted down the information and then turned to him. “Hey, Fernando, this must be your lucky day.”

He liked Linda, a leftover hippie from the 1970s who’d managed to preserve her sardonic sense of humor. He saw her peering over the counter at him, steel-gray Afro, thick glasses, and a big smile on her face. From years of experience he knew what her smile meant—big trouble.

“Yeah?” he asked tentatively, not really wanting to know.

“Guy by the name of José Padilla just called to report a homicide in Jacoñita.” Linda pushed the glasses back on her nose.

“Jacoñita? Where’s Jacoñita?”

“You know, out by San Ildefonso Pueblo.”

He nodded, remembering.

“Guess who our lucky victim is?”

Expecting the worst, he wasn’t disappointed when he heard Linda say, “Michael Soto.”

2

He shaded his eyes from the glare of the sunlight striking the tin roof of José Padilla’s house and wished he hadn’t forgotten his sunglasses. Just last week his wife had bought him an expensive pair that were supposed to block out 99.9 percent of all harmful rays. Estelle liked to warn him about cataracts, caused by too much sun coming through the deteriorating ozone layer. Leave it to his wife to always find something new to worry about.

Not surprisingly, Tomas Trujillo hadn’t forgotten his sunglasses. The Ray-Bans were an essential part of his look, as were the short-sleeve shirts rolled up even shorter to reveal the bulging muscles left over from his days as a linebacker on the Santa Fe High School football team that won the state championship a few years back. He didn’t care much for Trujillo—a deputy sheriff from Santa Fe Country—for the simple reason that Trujillo could never stop playing the tough guy. Trujillo had a short fuse and was always getting into trouble with his superiors for slapping people around. One of these days he would slap the wrong person and get his ass suspended.

He patted the pack of Camel Lights in his shirt pocket, always there if he needed them, while he listened to Trujillo and Padilla argue over by the crumbling adobe wall near the house. Padilla was a lousy liar, no doubt about it. He claimed not to have discovered Soto’s body until eight this morning, a few minutes before calling 911. That story wasn’t going to wash with anyone, because Soto had been dead at least eight hours by the time he and the lab technicians arrived.

The Porsche, with Soto’s body inside, had been parked all night in Padilla’s yard, no more than thirty feet from his front door. Not even a jury of his Hispanic peers would believe Padilla slept that soundly.

“Don’t give me that bullshit,” Trujillo said. “What happened last night? Why did you wait until this morning to call us?”

“I told you.” Padilla nervously glanced from Trujillo to Fidel, who was listening to their conversation and scribbling notes in his small reporter’s notebook.

“I noticed the car when I came out this morning. I was on my way to Santa Fe to buy groceries, and when I opened my gate—”

Trujillo stopped Padilla before he could finish the sentence. “Come on, you’re not dressed to go shopping.”

True, he thought. Padilla didn’t look all that presentable, wearing filthy white painter’s pants and a soiled blue denim work shirt. Not much of a looker anyway, with his wrinkled fifty-something face, he hadn’t helped his appearance any by not shaving or combing his hair. He reeked of smoke, as if he’d just returned from a camping trip. The nights weren’t cold enough for a fireplace or a wood burning stove.

Trujillo tried again. “What was Soto doing here last night?”

“Please,” Padilla pleaded. “I told you. I found him this morning.”

“Then what was Soto doing here this morning?”

Padilla looked at Fidel, as if searching for a friend.

“He came to buy something.”

“Like what?”

“He wanted to buy an old Hopi kachina I was selling. For his gallery.”

Trujillo persisted. “Why were you selling it?”

Padilla shrugged. “Because I needed the money.”

He turned away, letting their voices blend together.

Let Trujillo take care of the interrogation. He didn’t care, because it gave him more time to look around. He walked over to the shiny black Porsche, looking for something he’d missed earlier. Soto’s body had been slumped against the steering wheel when he and Fidel had arrived. The hole in the back of Soto’s head looked like the work of a small caliber bullet, maybe even a .22 fired at point-blank range. Soto was dressed casually, jeans and striped polo shirt, not the usual suits he wore around town playing the dandy.

Now that forensics had taken the body away, he could start his own investigation. Whoever killed Soto had been looking for something, that much was clear. How else to explain why the contents of the Porsche’s trunk had been tossed haphazardly on the ground? He found a duffel bag ripped open with such force that its zipper had torn loose from the leather. Someone had taken everything out of the bag—a freshly laundered shirt, a pair of chinos, and a black leather shaving kit.

There were other items scattered about the parking lot including a first aid kit and a small Navajo rug. He also found tourists brochures from Taos and Acoma pueblos, an AAA envelope stuffed with road maps, and a white cotton bag empty except for a fine brown dust that he couldn’t identify.

Had the killer found what he was looking for? Maybe, maybe not. He lowered his head and climbed into the passenger’s seat. Sitting in a Porsche was a new experience for him. He drove a Plymouth and had never, even in his youth, owned anything more exotic than a Ford Mustang.

Well, he had news for Soto and all the other yuppies. The Porsche was too goddamned small. Why pay ninety thousand dollars or more for a car that was too goddamned small? Soto might be able to answer that, but Soto was dead.

He studied the car. He thought he smelled smoke. Definitely a hint, a faint trace of wood smoke. It was enough to make him wonder if Soto and Padilla had been camping last night. It was a crazy idea, but at the moment he had little else to work with. The interior of the car was clean except for coagulated blood on the driver’s seat and the floor mat below. No apparent clues to what had happened last night. Opening the glove compartment, he found a flashlight and a map entitled “Guide to Indian Country,” published by the Automobile Club of Southern California.

He unfolded the map, which delineated, in great detail and color, the various Indian reservations in the Four Corners area, including parts of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Someone had taken a black felt-tip pen and traced along Highway 53, the back road to Zuni. The black marker followed Highway 53 as it dipped down from Grants, skirted the El Malpais lava flow, passed through El Morro National Monument, and then followed the Rio Pescado into Zuni. He found one other black mark on the map—a circle drawn around the tiny town of Whitewater, a few miles north of Zuni on the highway to Gallup.

He refolded the map and stuffed it in his back pocket.

Before getting out, he checked the pool of blood under the driver’s seat and noticed a few grains of fine white sand on the floor mat. Sand that fine and that white would have to come from the bottom of an arroyo. He climbed out of the car and looked around. He spotted an arroyo that began somewhere behind Padilla’s house and circled around to the west toward Black Mesa. It was worth a try. He stepped between two dusty green chamisa bushes just beginning to flower and walked over to the arroyo. Not surprised, he saw a scattering of footprints in the sand. There was no way to tell how fresh the tracks were.

He heard footsteps behind him.

“Wait up.”

He squinted into the sun, waiting for Fidel to join him.

“What do you think? Is Padilla lying?”

“Of course he’s lying. You think he wouldn’t notice a Porsche with a dead man inside parked all night in his front yard?”

Fidel nodded.

“Where does this arroyo go?” he mumbled, mostly to himself. He turned and walked along the edge of the arroyo, looking for some sign of recent activity, something. Fidel followed a few steps behind, careful to keep his distance.

Up ahead he saw Black Mesa rising from the desert floor, a slab of black rock silhouetted against the blue New Mexico sky.

He carefully made his way over the rough terrain, avoiding patches of cholla and prickly pear cactus while following the twists and turns of the arroyo. He noticed an abundance of animal tracks, dogs or coyotes, as he moved farther away from Padilla’s house. Then he noticed something else. Part of the bank had crumbled, as if someone had fallen over the edge. Loose rocks had collected at the bottom of the arroyo, near a place where the soft sand had been recently upturned. He thought he saw handprints.

He followed an imaginary line that began at the point of the handprints, passed through the spot where the bank had crumbled, and extended out indefinitely in the general direction from which someone running for his life would have come before stumbling into the arroyo. Soto, perhaps.

“Help me out. My eyes aren’t as good as they used to be. What do you see over there?”

Fidel looked in the direction he pointed. He studied the desert terrain. “Is that an old campfire?”

“Where?”

“Right there, to the left of the piñon trees,” Fidel answered.

He walked quickly toward the trees. He, too, spotted the remains of a campfire. A thin wisp of smoke coiled like a ghost over the black embers. As he approached he realized someone had poured water on the fire not long ago. He kicked at the charred pieces of wood that remained, watching the coals underneath begin to spark and recognized the scent of piñon wood.

It was the same smell he’d noticed on Padilla and in the front seat of Soto’s Porsche.

“Look at this,” Fidel said, pointing to a series of indentations in the sandy earth. The indentations were round, about four inches in diameter, and together formed a circle around the fire. The campfire had been located near the center of the circle. To be exact, the campfire had been located near the center of a teepee, which meant that someone had been camping here or holding some kind of ceremony. New Mexico was overrun with New Age types who were always going out in the desert for retreats and ceremonies of one kind or another, New Age religions or practices that he didn’t understand. He hoped it was that, not what he feared.

He squatted down on his haunches to get a better look. Near the fire someone had drawn, then later partially erased, a half circle in the sand.

He dug in the soft sand, carefully scraping away one layer at a time. He quickly found what he was looking for. What he hoped he wouldn’t find.

“Peyote,” Fidel said, when he held up the small brown button about the size of a quarter.

He nodded. “Soto came out here last night to attend a peyote ceremony.”

Fidel looked at him. “Native American Church?”

“Maybe.” He dropped the peyote button in his shirt pocket. “Give me a hand here.”

Fidel helped him up.

He took a bandana out of his back pocket and wiped his damp forehead. He was already sweating and the day was still young.

Overhead the sun scorched the blue sky, unusually hot for late August. He looked back at Padilla’s house and wished he’d remembered to wear his new sunglasses. Beginning to worry, he thought he could feel his eyes fogging up with cataracts. Soon he’d be blind. Then Estelle would say, “I told you so.” He’d have no one to blame but himself.

“So Padilla belongs to the Native American Church,” Fidel said, after a long pause.

He turned, remembering Fidel. “That’s why he didn’t report Soto’s body until this morning—to give them time to pack up the teepee and get the hell out of here.”

“Why would they want to conceal the meeting? The Native American Church is legal—”

He was interrupted by the sound of a distant “crack” and then the zing of a bullet kicking up sand just to their right in the direction of the arroyo.

“Get down!” he yelled, as the two dived into the sand.

Just then a second bullet struck behind them, closer to the house.

Fidel tried to get up.

“Wait!” He grabbed Fidel around the waist and pulled him back down. “Just listen.”

They heard nothing. Just silence. After about a minute, he rose to his knees slowly, looking around at the distant mesas over toward the Rio Grande. He saw no obvious places where a shooter could be situated. The shot was from a high-powered rifle, fired from a great distance. He could tell by the sound.

“Shit,” Fidel said. “I didn’t sign up for this, I’m a fucking news reporter.”

He ignored Fidel, standing up now and looking around for any possible movement on the mesas, a shooter, a vehicle, something.

“Where did it come from?”

He pointed toward the river. “Whoever it was, he’s probably gone now.”

“Yeah, well I’m getting the hell out of here.” Crouching low, Fidel scurried off into the sagebrush like a human crab, heading toward Padilla’s house.

He made a mental note to send someone out later to try and find one of the bullets. Good luck with that.

He frowned. The day was shaping up even worse than he expected. Getting involved with the Native American Church, or some renegade branch of the church, was the last thing he wanted to do.

Technically, Fidel spoke correctly. The courts had ruled that peyote ceremonies were legal if held as official meetings of the church. The legal issue didn’t bother him. Never had.

But having to deal with trigger-happy members of the church did bother him. They were the kind of people who gathered in teepees at night to gobble peyote, a hallucinogenic drug similar to LSD that induced visions of...what? The world of spirits and apparitions? He didn’t even know what to call it, never being one to believe in a spirit world. He was just trying to make sense of the one he inhabited, the physical world. Just thinking about the Native American Church gave him a headache.

He heard Trujillo’s loud, angry voice coming from inside the small adobe as he approached. He hurried inside, hoping he wouldn’t be too late to stop the rough stuff.

Fearing the worst, he breathed a sigh of relief when he found Padilla unharmed. The disheveled little man stood in one corner of his living room where he seemed to be showing Trujillo a finely carved kachina on the mantle above his fireplace. The kachina stood about eighteen inches tall, but brown and gold eagle feathers on its headdress made it appear much taller. The brightly-colored kachina danced in full costume, with a red cloth sash tied around its yellow waist, waving a gourd rattle in its right hand.

“Soto offered me five thousand dollars,” Padilla said. “It’s probably worth a lot more, because it’s a Hemis kachina carved in the nineteen twenties.”

He walked to the fireplace, negotiating a maze of worn sofas and stuffed chairs faded to a dull beige color. The other two men made room for him.

“When was Soto going to buy the kachina?” he asked suddenly. “Before or after the peyote ceremony?”

Padilla’s jaw tightened.

He could see the tension in Padilla’s face.

Trujillo looked puzzled, as if he’d missed something.

“I can’t talk about the church. Our ceremonies are secret. It’s a question of religious freedom.”

“Not when murder’s involved, it’s not,” he said, raising his voice.

Trujillo moved closer to Padilla, who shrank back against the whitewashed adobe wall.

“Now...I want you to tell me the names of everyone who came to the meeting last night. Then I want you to tell me exactly what happened. Everything from sunset to sunrise.”

3

Arms folded across his chest, he sat at his desk studying the peyote button he’d found at Jacoñita. The button looked harmless enough—brown, wrinkled, and no larger than a dried apricot. He knew peyote came from a small, blue cactus that grew wild in parts of southern Texas and Mexico. The cactus produced white flowers, as well as mushroom-like crowns that contained mescaline, a naturally occurring psychedelic drug that produced vivid hallucinations and deep introspection and finally nausea. Members of the Native American Church prized the dried crowns and used them in their all-night meetings. When chewed during the meetings, peyote induced extraordinary physiological and psychological effects such as visions, bright colors, and dramatic changes in time and perception. Some people argued that peyote unlocked the door to a separate, higher reality.

He knew peyote could be a potent drug, because he’d made the mistake of eating a couple of buttons one fourth of July afternoon at Cañjilon Lakes. It seemed like a million years ago—1968, or maybe 1969. The Lopez family—including an assortment of aunts, uncles, and cousins—had gone up to Cañjilon for a weekend of camping and fishing. His cousin Manuel, who was a member of the Native American Church, brought a bag of peyote and shared it with him and some of the older cousins. He could still remember wandering off by himself to lie in the grass and watch the sky change colors like a giant kaleidoscope. He didn’t remember how long he laid there, only the feeling of being incapacitated, unable to move.

Personally, he didn’t care much for the feeling, or for the sense of powerlessness he experienced while under the influence of the drug. The loss of control frightened him.

Manuel made fun of him. Called him a “tight ass” and lectured him on the importance of seeing beyond one’s individuality. Individuality was a prison, Manuel said.

Maybe so, but he wasn’t comfortable with the loss of control. That’s the way he’d always been. Manuel could go fuck himself if he didn’t like it. Which is what he had told him back in 1968. Whenever it was.

The Indians were different, of course. He had no problem with Indians using peyote. He knew the Navajo and Pueblo Indians had used peyote in religious ceremonies for hundreds of years before the Spanish arrived. Predictably, the Spanish tried to stop the practice by persuasion and, when that failed, force. No doubt about it, the Spanish had been heavy-handed in their efforts to stamp out the “pagan” religions of the indigenous peoples, issuing decrees that prohibited religious dances and other ceremonies, and destroying whatever religious masks and icons their searches uncovered at the various pueblos. Talk about stupidity. It always amazed him that people could be so lacking in judgment.

He did not consider himself religious, a fact that distressed Estelle, but even he recognized that the sword was not an effective means of religious conversion. Times had changed, or so his wife argued whenever they discussed this murky subject. But had they really, given the never-ending ethnic cleansing and sectarian violence that still plagued the world? He could trace his family’s presence in New Mexico back to 1630, the year Salvador de Lopez, originally of Valladolid, Spain, came to Santa Fe. A soldier and a blacksmith by trade, Salvador accompanied a mission supply train up the El Camino Real trail from Mexico City to Santa Fe.

He took pride in his family’s history and in the Spanish contribution to the cultural mix of New Mexico. Still, certain things bothered him, especially the religious persecution of the Indians. Today, most Hispanics chose not to remember that their ancestors brought the Inquisition to New Mexico. In 1625 friars acting as agents on behalf of the Holy Office of the Inquisition set up shop at Santo Domingo Pueblo south of Santa Fe. Some of the earliest Inquisition documents surviving at Santo Domingo concerned the “crime” of peyote use among the Pueblo Indians.

Shaking his head, he took the peyote button, protected by a plastic bag, and deposited it safely in his desk.

Already he saw some progress in the investigation. Padilla now acknowledged that Soto had died last night during the peyote ceremony. No big surprise there. By Padilla’s count eight people had attended the meeting—Sammy Tso and Dora Alvarez from San Ildefonso Pueblo, the five officers who conducted the ceremony, and Soto. While Padilla admitted to serving as Fire Chief, he denied knowing the identities of the other officers, only that the four of them—three men and one woman—lived somewhere near Gallup.

Just where in Gallup, Padilla refused to say. He claimed Soto had organized the meeting and that the other officers were friends of Soto’s.

So much bullshit, that last part. But he had to give Padilla credit. He proved to be a tough nut to crack. Not even Trujillo’s crude attempts at intimidation had broken him.

Once again he read Padilla’s statement:

“The meeting ended about midnight, just before Midnight Water Call. Peyote Woman and I stepped outside the teepee to get a pail of water. She came along to bless the water, but it was my responsibility as Fire Chief to bring it inside. When I turned to go back in the teepee, I heard footsteps coming up behind me. That’s when I saw him, the wolfman. He was wearing a wolf mask, with big white fangs and red tongue. I screamed at him to go away and leave us alone.

“‘Get out of my way!’ he shouted, then shoved me through the door of the teepee. The water spilled, and I fell on top of the pail. When I looked up, Michael Soto and the wolfman ran out of the teepee. Everyone was scared. We waited inside the teepee for about ten minutes, until we heard a gunshot. Then Road Chief went out to see what had happened. When he came back, he told us Michael Soto had been shot dead.

“Dora Alvarez started screaming and wouldn’t stop, so Sammy Tso took her home, back to San Ildefonso. Road Chief said a prayer to call off the meeting, and then we took down the teepee and the poles and loaded them on top of Road Chief’s van. The four of them left before sunrise, about an hour before I called you. That’s it, that’s everything that happened.”

Great. A werewolf was all he needed to make the day complete.

He tossed the paper back on his cluttered desk. He didn’t know what to make of the wolfman. Maybe Padilla had eaten too much peyote, so much that he’d experienced visions of ghosts and spirits and men turning into wolves under the light of a full moon. Or maybe, more likely, it was someone wearing a wolf mask. Someone who wanted Soto dead.

He checked the time. Nearly two p.m. Padilla had been waiting in the back room with Sergeant Antonio Blake for two hours now. They would have to release him soon enough, but Padilla didn’t know that. He hoped the wait with Antonio, a former Marine with notoriously gruff manners, would help refresh Padilla’s memory. Spending time with Antonio was like getting a dose of truth serum.

Finally he picked up the telephone. “Antonio, bring Padilla to my office.” He wanted to ask Padilla a few more questions before releasing him.

Antonio escorted Padilla into the office, then folded his arms and waited for instructions. An angry glare was fixed on the stocky ex-Marine’s face.

He noticed the change immediately. Padilla looked unsure of himself, nervous.

“Sit down.” He motioned to the gray metal chairs where Naranjo and Suino had sat a few hours earlier.

Padilla did as he was told.

He waved to Antonio, who disappeared down the corridor.

“First, I want to know more about Road Chief and the other officers. Who are these people? Do they usually travel together to the peyote meetings?”

“All I know is that Road Chief and his wife were friends of Soto’s.” Padilla sighed, tired of answering the same questions.

He raised his eyebrows. “Road Chief’s wife? Peyote Woman?”

“Right. They live out near Gallup. So do the others, I think. Like I told you before, Soto arranged the peyote meeting himself. He wanted to hold it near San Ildefonso, so I let him use my land. Soto did the rest.”

“But you served as Fire Chief.”

Padilla shrugged. “It’s common for the host to act as Fire Chief. Fire Chief watches the door of the teepee, brings in wood and tends the fire, things like that.”

“Was Road Chief a Zuni? Were any of the officers Zuni?”

“Zuni?” Padilla looked puzzled. “Road Chief’s an Anglo. So’s Drummer Chief and Cedar Chief. Peyote Woman might be Zuni. Some kind of Indian.”

He gave Padilla a legal pad. “Write down descriptions of them. Everything you can remember.”

He walked to the window and looked out through the Venetian blinds at the municipal parking lot that separated the police station from the new Santa Fe Public Library. He could still remember when the library was across the street, before some silly developer with the backing of City Council came up with the bright idea to build a pueblo-style mall called the First Interstate where the old library stood.

“Okay.” He walked back to his desk. “Now tell me this. Why did Soto want to hold the peyote meeting near San Ildefonso?”

Padilla blushed. “Well...he was looking for business.”

“Business? What kind of business?”

“For his gallery. It was like I told you before. He was going to buy my Hopi kachina. And I’d sold him other things, a couple of santos and a buffalo dancer kachina. So had Dora Alvarez, I think. That’s how Soto got a lot of the merchandise for his gallery. He bought it from people like Dora and me.”

He frowned, not liking what he was hearing. “You mean Soto staged the peyote meetings? He used the Native American Church in order to locate tribal objects and family heirlooms to buy?”

Padilla shrugged.

“Is that how he stole the ahayu:da?”

Padilla stared blankly at him. “The what?”

“The ahayu:da. Did Soto steal that, too? Or did he buy it from someone who did?”

Padilla shook his head, either confused or pretending to be confused. He couldn’t decide which.

“Some poor slob who had to sell his own tribal heritage for a few dollars?”

“So what?” Padilla shot back, raising his voice for the first time. “At least he paid for what he took.”

He glared at Padilla, surprised at the little man’s outburst.

Padilla no longer bothered containing his hostility. “Tell me, what else are we supposed to do? Sell fucking trinkets on the Plaza? We’re just trying to stay alive, like everybody else. Look at you. You’ve sold out to the system, you and all the other cops. Who do you think pays your wages? You set yourself against the People.”

“Yeah—fuck you, Padilla!” he snapped, having heard this bullshit before. “What people are you talking about? People like you? Thieves like you? Is that your definition of the People?” He fought hard to control his emotions.

“I’m leaving. If you want me, you know where to find me.”

He watched Padilla walk swiftly out of the office. He was sick and tired of punks like Padilla telling him that he’d sold out to the system. Being accused of selling out was a sore spot with him. He’d heard it repeatedly over the years and was fucking tired of hearing it.

Feeling claustrophobic, he pulled up the Venetian blinds and opened the window to let in some fresh air.

The gentle breeze on his face lifted his spirits. He needed to get out of this cluttered old office that stank of coffee and cigarette smoke and thirty years of police work. He decided to walk over to the Great Burrito Company for a cup of coffee and maybe something to eat.

The telephone rang before he could leave.

“Fidel Rodriguez from the Independent on line two,” Linda said from the front desk.

“Fernando, this is Fidel. I’m calling to find out if there’s anything new in the Soto case.”

Fernando sighed. “Nothing yet.”

“Yeah?” Fidel sounded skeptical, as though insinuating he was withholding something.

“Listen, will you do me a favor?” He changed the subject. “I need some background information. Do you know what an ahayu:da is?”

“You mean the Zuni war god?”

“Exactly. The Zuni carve the wooden figures and then place them in shrines on Zuni land. Sometimes the figures are stolen and end up in museums or private collections. Could you check your files at the Independent for any stories or photographs? Recent stories, especially.”

“No problem. What are you looking for? Is there a connection between Soto’s murder and a stolen ahayu:da?”

“Maybe. Two Zunis came to see me this morning. They think Soto was trying to sell an ahayu:da on the black market.” He could hear Fidel scribbling notes at the other end of the line.

“I’ll be over in a few minutes.” He hung up quickly before Fidel could ask any more questions.

On his way out he winked at Linda.

She smiled and shook her head. “Don’t start.”

He walked down to the Great Burrito Company and ordered a cup of coffee to go, ignoring the tourists sitting at the outside tables. He took the coffee up Marcy Street to the office of the Independent. Only ten minutes had passed since he’d hung up the phone, but that ought to be enough time. If Fidel was as efficient as he suspected.

“Bueñas Dias,” he said to Adellita, the receptionist, as he walked into the newsroom.

Adellita smiled, a young woman with streaks of red sprayed in her hair and tattoos on her bare arms. He didn’t get it. Why would anyone want sprayed red hair? Or tattoos on their arms?

Fidel waved him over to his terminal. “We have one photo in our file. It’s a reproduction of a nineteen twenty-five photograph taken by Edward S. Curtis. The original comes from the Museum of New Mexico Photo Archives. I’ll give you the negative number and our librarian will make you a copy.”

“Thanks.” He spilled coffee on the carpet as he took a seat at the next terminal.

“The most recent story I can find dates from this past spring when an ahayu:da was stolen from its shrine near Thunder Mountain on the Zuni Reservation. As far as I know, it hasn’t been recovered. Before that we go back two years, when an ahayu:da turned up in a Paris auction house. Paris, France. The Zuni took the auction house to court and argued that the bill of sale for the figure was invalid because sacred tribal objects were communal property and could not be sold by an individual. The case is still making its way through the courts.”

“Nothing more recent?”

Fidel punched a few more keys at his terminal and then shook his head. “Wait, here’s something else. Several years ago the Zuni successfully pressured the Smithsonian Museum to return an ahayu:da that had been part of the Frank H. Cushing Collection at the Smithsonian.”

He squinted at the monitor, trying to read the screen. “The what?”

“The Frank H. Cushing Collection. You know, the ethnologist who lived at Zuni Pueblo in the eighteen eigthies.”

While they talked, a young woman with long blond hair tied behind her head in a ponytail walked into the newsroom. “Here’s a copy of the photo you wanted.”

“Thanks, Anne.”

Fernando scooted his chair closer. “So that’s what an ahayu:da looks like. I’ll be damned.”

“See, there are actually two kinds, Big Brother and Little Brother.”

He studied the black and white photograph that showed a pile of ahayu:da in varying stages of decomposition. Two of the carved figures stood erect, rising out of a small patch of dried grass and prickly pear cactus, a Big Brother in front and a Little Brother behind.

Just as Fidel said, the two figures were entirely different. Big Brother displayed an elongated, helmet-like face and what looked like a phallus sticking straight out from its middle. More abstract and unformed, Little Brother had no face or phallus, but instead a series of geometric shapes carved on its body—half moons, circles, and crosses.

Fidel laughed. “This is supposed to be an umbilical cord.” He pointed to Big Brother. “In spite of what it looks like.”

But he wasn’t looking at Big Brother. He couldn’t take his eyes away from the symbols carved on Little Brother.

Where had he seen them before? Then he remembered. The very same symbols were drawn in the sand at Jacoñita, in the circle of the teepee.

4

He had never been inside Sabado Indian Arts on the Plaza, one of the newer galleries in Santa Fe. He found himself sitting in the back office with store manager Wanda LeClair, a small shapely woman with strawberry blond hair wearing a tight black dress that revealed every curve. Like Soto, she was drop dead gorgeous, one of the Beautiful People. Except they weren’t so beautiful now. Soto was dead and she had been weeping nonstop since he’d delivered the news about her boss. To escape her blubbering, he walked into Soto’s office and took a seat at the desk. Unfortunately, she followed him, bringing with her a box of tissues. She sat on the black leather sofa wiping her eyes with one tissue after another.

The sound of women crying made him uncomfortable. Something to do with male guilt, he supposed, though he didn’t really care to explore the subterranean levels of the male psyche, his in particular. Too much self-knowledge could be a dangerous thing.

He knew very well that he should say something consoling to her, since he’d been the indirect agent of her grief, having delivered the bad news. Her decision to follow him into the office meant that she expected him to offer comfort of some sort. But what, precisely, could he say or do? Bring Soto back to life? If he could do that, he wouldn’t be wasting his time working for the Santa Fe Police Department.

“I’m sorry,” he said finally. It wasn’t much, but enough to break the impasse.

She nodded and reached for another tissue. “I just can’t believe it. Everyone loved Michael. He was such a nice guy.”

“Not everyone.”

She looked at him in horror, as though he’d uttered something disrespectful to the dead, something obscene.

Taken aback by her reaction, he fumbled for the right words. “What I mean is, Soto had at least one enemy. Can you think of anyone who might have had a reason to kill him? A dissatisfied customer, perhaps.”

She shook her head and brushed the hair out of her eyes, no longer weeping.

“Or, let’s say someone who wanted to get back a sacred tribal object...one that Soto might have been selling on the black market—an ahayu:da, for example?”

“What’s that? You mean the Zuni War god? The carving?”

“Correct.” He explained about the stolen ahayu:da and the letter Suino and Naranjo had shown him earlier.

She shook her head again. “I don’t believe it. Michael wasn’t the type to deal in black market art. Why would he? He made a lot of money selling legal Indian art.”

He shrugged, not getting a read on this woman. Was she as innocent as she pretended? Or was she covering up her involvement in Soto’s black market business?

“Well,” he said finally. “We do know he pretended to be a member of the Native American Church in order to buy tribal objects from the people he met at peyote meetings.”

“Michael may have gone to some peyote meetings to meet people, to make contact with craftspeople and clients, but he wasn’t selling on the black market, I’m sure. I mean, I think I would have known if he was doing something illegal. We were very close.”

“How close?”

“Close enough to know if he were selling stolen property.”

Watching her performance, he began to wonder if she had been in love with Soto. Naturally all the women would fall for someone like Soto. He was handsome, slick, and obviously rich.

“Excuse me. I need to look around the office. If you don’t mind.”

Taking the hint, she stood up with her box of tissues. Then she turned and walked out.

He fidgeted at the desk. Soto’s office was a study in black and white: black furniture, white walls. Even the expensive Navajo rugs hanging on the wall were woven of black and gray wool. The room needed some color, he decided. Surely, with a gallery filled with colorful Indian arts—rugs, pottery, and jewelry—Soto could have added a splash of color to the room. Even one of the kachinas behind the counter would have helped.

He went over to the emergency exit and threw open the back door, exposing the narrow brick alley. It contrasted sharply with the slick interior of Soto’s office. He studied the crumbling brick and adobe walls, splotched with layers of mud stucco and covered with graffiti.

The patched, discolored walls, even the overturned trash cans in the alley cheered him slightly, though he couldn’t say exactly why. The slogans spray-painted on the alley walls were as ugly here as they were elsewhere around the city. Throw open the door, look underneath the glitz, and what do you find? “Go back to Texas.” “Fuck you, Anglo pigs!” Everywhere the same tensions, sometimes hidden, sometimes not.

He walked back to the desk and put up his feet, thinking. He’d already examined the contents of Soto’s desk, including computer printouts listing each item in Sabado’s inventory by number and description, date and price of purchase, and date and price of sale, if sold. None of the entries on these lists looked suspicious, which probably meant that Soto kept his black market activities off-list. The desk also contained a collection of business cards from art galleries in New Mexico and Arizona that Soto may have done business with. Odds and ends. No mention of the ahayu:da.

One thing he did find was a locked broom closet at the end of the hallway, which made him wonder why anyone would lock a broom closet. When he asked to open the door, the LeClair woman said she didn’t have a key, that Soto kept the only key to the closet. That meant he would have to get a warrant and a locksmith to open the door one way or another. He could do all that tomorrow when he had more time and patience.

Still, the possibility that he might be overlooking something else, something obvious, kept him from leaving. He checked his watch. Still enough time to drive out to Hyde Park Estates, where Soto had recently purchased a new condo, and make it home by six thirty.

His wife hated for him to be late for dinner, even after all these years of police work. Estelle had never gotten used to his irregular hours. For thirty years she’d stubbornly refused to reconcile herself to the unpredictable and often inconvenient disruptions of daily routine that came with his job.

Maybe non-acceptance was her form of acceptance. Did that make any sense?

While he considered what to do next, he heard voices coming from the front of the gallery. Wanda was explaining to someone that the gallery was closed for the day. “No, I’m sorry, but you’ll have to leave,” she said, raising her voice. Apparently her words had no effect, because the very next moment she shouted, “Wait! Where do you think you’re going? Stop or I’ll call the police.”

Had she forgotten about him? He was, after all, the police.

He listened to the approaching footsteps. Loud, angry footsteps. Suddenly two men burst into the office, with Wanda following closely on their heels. The Los Angeles Dodgers baseball cap tipped him off even before he got a good look at the faces of Suino and Naranjo. Immediately his spirits sank. He would never make it home by six thirty now.

Estelle would not be happy tonight.

The two Indians paused momentarily when they saw him sitting with his feet up on the desk. Naranjo looked nervous, but not Suino. Suino began to search the office, as if he didn’t exist. An invisible man.

“What the hell do you want?” He was not happy with this unwanted intrusion.

“I told them we were closed, but they wouldn’t listen,” Wanda said.

Suino ignored her. “What do you think we want? We’re looking for our ahayu:da. We didn’t find it in Soto’s room at La Fonda, so now we’ve come to check his gallery.”

He took his feet off the desk and sat up straight. “What are you talking about? Soto lives in Hyde Park Estates.”

Suino looked at him blankly, a look of incredulity on his young face.

“Not exactly,” Wanda interjected, embarrassed for him. “That’s a mistake. The new directory lists his address as Hyde Park Estates, but his condo isn’t quite finished, so he’s living at La Fonda. Had been living at La Fonda.”

Suino looked at him. “You didn’t know that?”

He ignored the question. He stared at Suino for a few moments, then changed the subject. “I forget. Where did you say you were staying in Santa Fe?”

Naranjo answered, sucking in his big belly. “Tesuque Pueblo.”

He smiled. By his calculation Tesuque Pueblo was less than ten miles from Jacoñita—logistically, an insignificant distance for a murderer bold enough to stalk his victim at a peyote ceremony. A wolfman, perhaps. Or someone pretending to be a wolfman.

“Both of you stayed at Tesuque Pueblo last night? Is that correct?”

Naranjo nodded.

“So what?” Suino wanted to know.

“I’ll tell you so what.” He stood up from the desk and walked toward Suino. “Someone murdered Michael Soto last night at Jacoñita, a few miles from Tesuque Pueblo.”

“Yeah? Did Soto have the ahayu:da with him?”

‘We don’t know if he had the ahayu:da with him, but the person who killed him went through his car trying to find it. So tell me, were you in Jacoñita last night?”

“Then it’s still missing.”

“Answer my question!” he shouted.

“How can you find anything sitting around here?”

Losing control, he grabbed Suino by the T-shirt and slammed him back against the wall, cracking the plaster. He twisted the collar around Suino’s neck, choking him.

Suino grabbed his hand and tried to push him away, but he slammed him back into the wall again. Plaster showered the floor.

The sudden violence surprised Wanda, who screamed and ran out of the office.

Naranjo pleaded with him. “Don’t hurt him, please. He’s just a smart-ass kid.”

He felt the blood pounding through his veins, and he heard the muffled voice of Naranjo talking to him. It took a moment, but he managed to control his impulse to smash Suino’s face. Finally he let go of the T-shirt, and then tried to smooth the twisted fabric by patting it against the man’s chest.

It had been a long time since he’d lost his temper like that. He didn’t like the feeling. He needed to do a better job of controlling his emotions.

Suino stared impassively at him, pure hatred in his eyes.

“Come with me—both of you. We’re going back to La Fonda.” He brushed past Wanda, who stood watching from the safety of the doorway, then marched across the wooden floor of the gallery. He heard Suino and Naranjo following along behind.

Walking the short distance to La Fonda didn’t provide enough time for an attitude adjustment. When he stepped into the colorful Mexican-style lobby, hand painted tiles and potted palms, he found it almost as crowded as the Plaza. He heard mariachis playing in the bar and the murmur of a hundred voices talking at once. Oddly enough, he spotted the hulking figure of Antonio at the front desk, talking to Fred Mondragon, the manager.

Some sort of disturbance must have occurred, because Antonio was taking notes while Mondragon gestured toward a bellhop who stood between the two older men. What the hell now? He pushed his way through the crowd toward the blue uniform of Antonio who, at six feet seven inches tall, towered over Mondragon, the bellhop, and everyone else in the noisy lobby.

“What’s the problem?”

Antonio shook his head. “Got a report here that two Indians were seen prowling around upstairs.” He sounded annoyed, as if he thought the whole thing was a waste of his time.

“Not prowling,” Mondragon protested, a neat little man wearing a tan suit and a necktie that was as white as his hair. “Jimmy saw them come out of one of the rooms. Go on, tell the man, Jimmy.”

The bellhop started to say something, then stopped abruptly when he saw Suino and Naranjo coming up behind him. “There. That’s them.” He pointed at Suino and Naranjo. “The two men I saw leaving the room.”

“Grab them!” Mondragon shouted.

But Suino was too fast. He shoved him hard in the back, sending him flying into a man wearing a backpack and then into a tall beanpole of a woman wearing a straw sombrero. Falling, he grabbed the woman around the waist and felt his nose press up against the heavy squash blossom that dangled between her breasts.

“Get off me!” the woman screamed, swatting him on the head with her purse. The blow knocked him sideways and sent him reeling to the floor, where he landed on his elbow. He gasped for air as a sharp pain shot up his right arm into his shoulder. By this time everyone in the lobby seemed to be pushing and shoving and shouting at one another.

He tried to make amends. “Sorry...sorry.”

Amid the chaos, he struggled to a sitting position, fearful of being trampled by the mob of rowdy tourists. No way he could let that happen, he told himself, struggling to get to his feet. Luckily, the tall woman with the sombrero had been pushed back toward the bar where she staggered from side to side like a wounded animal, screaming and flailing away with her purse at anyone who came near enough for her to swat.

“Stop it!” Mondragon shouted, raising his arms. With the help of the bellhop, he climbed up on the front desk and looked down on the angry mob. “Please. Calm down. Stop pushing. There’s been a misunderstanding. Please. Clear out and give us some room. Someone’s been injured.”

He realized that Mondragon meant him. He was the injured person.

Slowly the crowd began to disperse.

As the noise subsided, he could hear Antonio speaking to him.

“Are you okay? Fernando? Are you okay?”

“Yeah...sure...I think so.” He let Antonio help him to his feet. He rubbed his sore arm and then glanced around the lobby.

“They’re gone. They ran outside. Someone said they went up San Francisco Street past the cathedral.”

He frowned. “I know where to find them.” He turned to Mondragon. “Do you want to press charges?”

Mondragon shook his head. “Not really. Not if you can keep them out of here. They didn’t take anything, according to Jimmy. So why bother, unless they come back.”

Both Antonio and the bellhop had to help Mondragon down from the front desk.

Leaving Antonio to make peace in the lobby, he got a key to Soto’s room from the front desk and took the elevator to the fifth floor. As soon as he stepped out he lit his emergency cigarette, tossing the match on the terra-cotta tile floor. The burst of nicotine picked him up immediately, just enough to make him feel capable of taking care of this last piece of business. He bypassed the chance to rest a moment on the hand-carved bench in the sitting area across from the elevator. For a little while longer he would have to run on sheer determination.

Down the dark carpeted hallway—its walls lined with Mexican tiles and pressed-tin light fixtures—he found Soto’s room and unlocked the door. The room turned out to be a small suite complete with sitting room, bedroom, and bath. There was even a balcony overlooking La Fonda’s pool three floors below. The pool shocked him. He had no idea La Fonda had such amenities. Imagine that. Living in a city for sixty years and not knowing that its most famous downtown hotel had a swimming pool. What else didn’t he know about Santa Fe?

“This is a non-smoking room,” someone said from the hallway behind him.

He turned to find a skinny maid with chemically blond hair carrying a stack of clean towels.

“I’m a police detective.” He showed her his badge.

She ignored the badge. “Did you know that John Kennedy stayed in this room when he came to Santa Fe in nineteen sixty?”

“No kidding. So Kennedy and Michael Soto have at least two things in common.”

“Two things?” The maid looked puzzled, waiting for an explanation.

“If you will excuse me.” He closed the door in her face.

Once again he could not locate an ashtray, so he tossed his cigarette in a potted cactus by the door. Then he crossed the room and stepped out on the balcony, which turned out to be a mistake because as soon as he did he spotted the tall woman with the sombrero sitting at a poolside table sipping a gigantic mixed drink. Even from this distance he could see the pink color of the murky concoction, complete with doll-size umbrellas. When the woman pointed him out to her companions, two other women wearing layers of turquoise jewelry, he frowned and went back into the room.

A horrible thought occurred to him. Maybe he would keep running into this woman. Forever.

Sitting on the Taos sofa, he surveyed the room. He couldn’t help but admire the handcrafted furniture, all rubbed with the same gray wash and embellished with the some motifs, zigzag arrows, bear claws, and feather plumes. Not bad for five hundred dollars a day, or whatever Soto paid to live at La Fonda. The sitting room came equipped with a wet bar stocked with bottles of scotch, tequila, and exotic liqueurs. Not bad at all. He put his feet on the coffee table and looked around the room, impeccably arranged and decorated in the best Southwestern style. For people who could afford it.

People like Soto. And John Kennedy.

But for all the expensive Southwestern décor, the room still looked like a sterile hotel room. In contrast, the bedroom looked lived in. On the floor he found a pile of books, a plastic bag stuffed with soiled clothes, and a cardboard box containing Indian pots, individually wrapped in plastic foam.

He checked the two side-by-side trasteros that served as closets. Soto’s collection of Giorgio Armani suits impressed him, as did the rows of silk and linen shirts. A real yuppie, all right. Too fancy for his taste. Then something caught his eye in the second trastero. A row of women’s clothing. Dresses and an assortment of skirts and blouses. Interesting. Either Soto enjoyed cross-dressing, or he’d had a frequent overnight guest. Wanda LeClair?

After he finished rummaging through Soto’s clothes, he decided to call it quits. He’d have to come back tomorrow when he had more time, and more energy. Leaving, he noticed a photograph on Soto’s nightstand. A small photograph in a silver frame of an attractive middle-aged woman standing between two teenage boys, both of whom looked like Michael Soto, sleek and darkly handsome even at that raw age. He guessed it was Soto with his mother and twin brother, even though the woman happened to be blond and fair-skinned, clearly an Anglo. Did that mean Soto’s father had been Hispanic?

Who was Soto? Now the question began to interest him.

But the clock on the nightstand reminded him of the time. Nearly seven. Estelle would be furious.

He wondered if he should call her. Or would calling now, at this late hour, upset her even more? Unable to decide, he retraced his steps to the desk in the living room. When he saw he red light on the phone, he thought for a moment that Estelle might be trying to reach him.

A crazy idea. How would she know where to find him?

He called the front desk.

“Let’s see...yeah, Soto has a message from yesterday,” the desk clerk said. “Call Reno.”

“Reno?” he was confused. “The city of Reno?”

“I don’t know. Call Reno. That’s all it says.”