Читать книгу Indian Rock Art of the Columbia Plateau - James D. Keyser - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

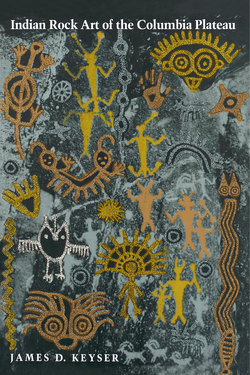

ОглавлениеIntroduction

SCATTERED THROUGHOUT THE Pacific Northwest are hundreds of prehistoric rock paintings and carvings made by the Indians of this region prior to European American settlement of the area. These pictures, carved into basalts along the Columbia River and its tributaries, or painted on cliffs around the lakes and in the river valleys of western Montana, British Columbia, northern Idaho, and Washington, are an artistic record of Indian culture that spans thousands of years. Collectively called rock art by the scientists who study them, these drawings are most often carefully executed pictures of humans, animals, and spirit figures that were made as part of the rituals associated with religion, magic, and hunting.

Rock art in the Pacific Northwest was first noticed by early explorers. Before the turn of the century, government-sponsored expeditions searching for wagon and railroad routes through the region noted rock art at Lake Chelan, along the lower Columbia River near Umatilla, and in northern Idaho. Soon after, anthropologists and other scientists began studying some of these sites. James Teit, an ethnologist who recorded the cultures of Columbia Plateau Indian tribes in British Columbia and northern Washington between 1890 and 1920, interviewed natives who had painted some of these pictures and asked why they had done so (Teit 1928). Since then, his work has been a key to all serious rock art research in the region. Since 1950, numerous scientific articles and two small books about Columbia Plateau rock art have described and discussed the paintings and carvings of many areas in the Pacific Northwest (Boreson 1976; Cain 1950; Corner 1968; Keyser and Knight 1976; Loring and Loring 1982; McClure 1978).

Despite this long history of scientific interest in Columbia Plateau rock art, the public remains relatively unaware of these paintings. Except for occasional newspaper or magazine articles, and limited interpretation of a few sites, little information on rock art has been made available to nonscientists. One result has been the spread of misinformation by sensationalist writers, who have suggested that these drawings are maps or “writing” left by Chinese, Norse, Celtic, or other pre-Columbian explorers.

More serious, however, is that current residents of and visitors to the Pacific Northwest miss the opportunity of understanding and appreciating rock art as a part of our region’s rich cultural heritage. This has led to the defacement (and even the destruction) of some sites by unthinking vandals who obliterate the original art with spray-paint scrawls. Thus, my purpose in writing this book is to help interested persons understand the age, meaning, and function of this art. I hope that this will lead to public appreciation of and concern for these irreplaceable art treasures of our past.

What Is Rock Art?

Simply put, rock art can be defined as either engravings or paintings on nonportable stones (Grant 1967, 1983). Because it is the subject of scientific study, a set of specialized archaeological terms and a technical vocabulary convey exact nuances of meaning to professional scholars. These terms can be confusing to the lay reader, and since the primary purpose of this book is to provide an overview of Columbia Plateau rock art and to describe in general its origin, function, and age, I have used a minimum of this professional jargon. Some terms cannot reasonably be avoided, however, due to the specialized nature of the subject matter. Thus, I define here six terms which may need clarification: petroglyph, pictograph, anthropomorph, zoomorph, rock art style, and rock art tradition. Each of these can also be found in the glossary, which contains a few other specialized terms used occasionally throughout the book.

Petroglyphs

Petroglyphs are rock engravings, made by a variety of techniques. In the Pacific Northwest, pecking was the most common method: the rock surface was repeatedly struck with a sharp piece of harder stone to produce a shallow pit that was then gradually enlarged to form the design. Some Columbia Plateau petroglyphs were also abraded or rubbed into the surface with a harder stone to create an artificially smoothed and flattened area contrasting with the naturally rough-textured rock. Pecked designs were sometimes further smoothed by abrading.

A few Pacific Northwest petroglyphs were made by scratching the rock with a sharp stone flake or piece of metal to produce a light-colored line on the dark surface. Some shallow scratches are now nearly invisible, having weathered over several hundred years. Others were deepened to form distinct incisions still readily apparent. A few petroglyphs show a combination of techniques; most common are animal figures with abraded bodies and scratched legs, horns, or antlers.

Columbia Plateau petroglyphs are most often made on basalt, a hard, dense volcanic stone. The weathered surface of basalt is a dark, reddish-brown to black patina, or “crust,” several millimeters thick. Underneath this patina the stone is a lighter color, ranging from yellowish brown to dark grey. Prehistoric artists engraved deep enough to reveal this un-weathered interior stone so that designs would stand out against the darker background. Reweathering of designs exposed in this way provides a clue to help in dating some petroglyphs.

Pictographs

Pictographs are rock paintings. On the Columbia Plateau these are most often in red, but white, black, yellow, and even blue-green pigments were sometimes used. Polychrome paintings are uncommon, but a few do occur throughout the region. Most frequent are the red and white polychromes of the lower Columbia River and Yakima valley.

Pigment was made from various minerals. Crushed iron oxides (hematite and limonite) yielded red—ranging from bright vermilion to a dull reddish brown—and yellow colors. Sometimes these ores were baked in a fire to intensify their redness. Certain clays yielded white pigment, and copper oxides blue green. Both charcoal and manganese oxide produced black. Early descriptions indicate that Indians mixed crushed mineral pigment with water or organic binding agents, such as blood, eggs, fat, plant juice, or urine, to make paint.

Pigment was most commonly applied by finger painting: finger-width lines compose the large majority of pictographs throughout the area. Some paintings, done with much finer lines, indicate the use of small brushes made from animal hair, a feather, or a frayed twig. Still others were drawn with lumps of raw pigment (much like chalk on a blackboard) or grease-paint “crayons.” These pictographs have a characteristic fine-line appearance, but the pigment appears somewhat unevenly applied in comparison with the small brush paintings.

How this paint has survived on open exposed cliff faces, where pictographs are usually found, has long been the subject of scientific debate. Early scholars, presuming that the paint would fade rapidly, argued that all of these paintings had been done during the last two hundred years. Several reported significant fading at some sites, and even suggested that none of these paintings would last beyond a few more years. Fortunately, they have been proven wrong: scientists have recently discovered evidence that the paintings are not disappearing, as originally thought. Photographs taken at several sites over spans of as much as seventy-five to one hundred years indicate that pronounced fading is not usually a problem. Often, “faded” pictographs are found to have been destroyed by road construction, inundated by reservoirs, or covered by road dust or lichen. When affected only by natural weathering, paintings at hundreds of sites remain as bright today as when they were first discovered.

Recent research by Canadian scientists (Taylor et al. 1974, 1975) has demonstrated why these rock art pigments are so durable. When freshly applied, the pigment actually stains the rock surface, seeping into microscopic pores by capillary action as natural weathering evaporates the water or organic binder with which the pigment was mixed. As a result, the pigment actually becomes part of the rock.

Mineral deposits coating many cliff surfaces provide a further “fixative” agent for these paintings. Varying types of rock contain calcium carbonates, aluminum silicates, or other water-soluble minerals. Rain water, washing over the surface of the stone or seeping through microscopic cracks and pores, leaches these naturally occurring minerals out of the rock. As the water evaporates on the cliff surface, it precipitates a thin film of mineral. This film is transparent unless it builds up too thickly in areas with extensive water seepage. In these instances the mineral deposit becomes an opaque whitish film that obscures some designs, the reason that some pictographs do actually fade from view. However, microscopic thin section studies show that, in most instances, staining, leaching, and precipitation have actually caused the prehistoric pigment to become a part of the rock surface, thereby protecting it from rapid weathering and preserving it for hundreds of years.

Anthropomorph, Zoomorph

Anthropomorph and zoomorph derive from the Greek words morphe, “form”; anthropos, “man”; and zoon, “animal.” Thus, anthropomorphs have human form, zoomorphs have animal form. These words are often used instead of “human” and “animal” in the professional literature to communicate a specific meaning because scientists cannot be sure that the original artist intended a specific figure to represent an actual human (or animal), or merely the concept of humanness, or even the personification of a spirit or other nonliving thing. However, in this book, the terms “human,” “human figure,” “animal,” and “animal figure” are more readily understood, and fine distinctions of meaning are not required.

On the other hand, I have used these two terms when it is obvious that the prehistoric artist did not intend to represent a real human or animal, yet used undeniably human or animal features in a design. Multiple-headed beasts, faces that combine some features of both humans and animals, or otherwise abstract designs incorporating clearly recognizable body parts are categorized as anthropomorphic or zoomorphic, depending on which features are primary. Thus, a grinning human face with a fish tail would be anthropomorphic, while a three-headed animal figure with hands in place of hooves or paws would be referred to as zoomorphic. For the most part, however, if a figure closely resembles a human or an animal (given stylistic conventions), I refer to it using the simpler terms.

Rock Art Style and Rock Art Tradition

Rock art style and rock art tradition are also technical terms with specific meanings. Researchers world-wide define rock art style as a group of recurring motifs or designs (e.g., rayed arc, human figure) portrayed in typical forms (e.g., alternate red and white rays, stickman), which produce basic recognizable types of figures. Usually these various figures are associated with one another in structured relationships, leading to an overall distinctness of expression. Thus, we can define the Yakima polychrome style and easily distinguish classic examples of it from the central Columbia Plateau style, which used the same rayed arc motif and stick figure humans, but in significantly different forms, numbers, and structured relationships.

The characteristics of styles vary across space and through time, however, and some blending occurs between neighboring styles. For instance, some highly abstract anthropomorphic figures that are undoubtedly in the Long Narrows† style are executed as elaborate polychrome paintings more like characteristic Yakima polychrome motifs. Likewise, a few of the rayed arcs characteristic of the western Columbia Plateau style occur in the eastern part of the region, although not as an important motif. This blending occurs to some extent between almost all art styles that are contemporaneous and geographically associated, and sometimes artists will even copy motifs from much older styles, thereby bridging the gap of time.

The greatest blending, however, occurs among styles whose makers are culturally related and who have regular contact with one another. The result is a rock art tradition, extending through time in a defined area, which has two or more styles that are more similar to each other than to any neighboring style. Such is the Columbia Plateau rock art tradition, where stick figure humans, simple block-body animal forms, rayed arcs and circles, tally marks, abstract spirit beings or mythical figures, and geometric forms are combined to produce an art that is recognizably distinct from that of the neighboring areas of the Northwest Coast, Great Basin, or northwestern Plains.

Rock art styles have been generally identified as naturalistic, stylized, and abstract (Grant 1967). Naturalistic art depicts actual things, such as humans and animals, in a reasonably realistic or natural manner. Stylized art renders recognizable forms in a highly conventionalized or nonrealistic manner. Finally, abstract art shows forms that are unrecognizable as naturally occurring things. Of course, no art is composed exclusively of only naturalistic, stylized, or abstract forms, but classification is determined by the type of designs that predominate (fig. 1).

Pacific Northwest rock art is primarily naturalistic, with the exception of the Long Narrows and Yakima polychrome styles localized in the lower Columbia area near The Dalles, Oregon, and a few pit and groove style sites scattered throughout the region. Most Columbia Plateau rock art shows simple stick figure humans and block-body animal figures, rayed circles or arcs, and tally marks. Geometric abstract figures occur in smaller numbers. Frequently, humans and animals are arranged in a composition, often with an associated geometric design such as a rayed arc, circle, or group of dots. The resulting structured composition appears to portray some sort of relationship between naturally occurring objects.

In the lower Columbia area two significantly different art styles—the Long Narrows and Yakima polychrome styles—occur. Dating from approximately the last thousand years, these drawings show an increasing stylization of the human form that culminates in the portrayal of humans and spirit beings as complex mask designs, often with grotesquely exaggerated features. Some animal forms also become more stylized, and polychrome rayed arcs and concentric circles become major components. Apparently Northwest Coast art traditions, which show a somewhat similar evolution of stylization, heavily influenced these two styles. Quite likely, the Columbia River’s use as a major prehistoric trade route from the coast to the interior was partly responsible for the evolution of this stylized art in The Dalles region.

Highly abstract art is not common on the Columbia Plateau. Throughout the region, occasional sites have drawings composed almost exclusively of cupules, dots, and meandering lines; rarely are humans or animals depicted. These sites appear most closely related to the curvilinear abstract art called pit and groove and the Great Basin abstract style that occur throughout the western United States, primarily in the Great Basin area of Nevada and California.

1. Chart of rock art styles

Dating Rock Art

Determining the actual age of most Columbia Plateau rock art sites is difficult to do with certainty, except in instances showing horses or other objects of known historic age. However, a variety of techniques, in combination with the study of stylistic evolution, can sometimes establish relative ages. Six major factors provide clues to general dating of Columbia Plateau rock art: (1) association with dated archaeological deposits, (2) association with dated portable art, (3) portrayal of datable objects, (4) superimposition of designs, (5) patination, and (6) weathering (McClure 1979a, 1984).

Association with Dated Archaeological Deposits

Occasionally, sediment containing dated archaeological items will bury a rock art panel. This may occur in a rock shelter or on an open site where sediment builds up against the rock surface, or when a portion of a rock art panel falls from a vertical surface into an archaeological deposit below. Neither occurrence is especially common, since both require the propinquity of rock art and living areas, rapid deposition of sediment, or partial destruction of the site.

Two examples of buried rock art provide dating clues for the Columbia Plateau. In south-central Oregon, a deeply carved panel of abstract petroglyphs is partially covered by a deposit containing ash from the volcanic explosion of Mount Mazama that formed Crater Lake sixty-seven hundred years ago (Cannon and Ricks 1986). Thus this site demonstrates that Pacific Northwest Indians must have been making abstract petroglyphs before this early date. Of more direct relevance to Columbia Plateau rock art was the discovery—in Bernard Creek Rockshelter in Hells Canyon on the Snake River—of a spall, from the rock shelter wall, that bore traces of red pigment. The painted spall was found in a level that dated between six and seven thousand years ago (Randolph and Dahlstrom 1977). Although it could not be matched to any paintings still visible in the shelter, the fragment does demonstrate that Columbia Plateau Indians have painted pictographs for a very long time.

Association with Dated Portable Art

Many of the ancient Paleolithic paintings and carvings in the famous caves of France and Spain can be fairly securely dated because they closely resemble engraved designs on animal bone that have been found in dated archaeological deposits. In these cases, the portable art and the rock art are sufficiently similar in style and technique to infer that they are contemporaneous. Unfortunately, on the Columbia Plateau portable art is not often found in well-dated contexts, but a few examples are known. Probably the most definitive are near The Dalles, where a number of Tsagiglalal carvings have been found in cremation burials that date between A.D. 1700 and A.D. 1800, and almost identical Tsagiglalal petroglyphs occur on nearby cliffs. Certainly, given the stylistic complexity of this figure, both the portable and rock art examples must be of the same age.

Elsewhere at sites along the middle Columbia, archaeologists have recovered a few pieces of stone and bone sculptured in human and animal form. Some of the human forms show distinctly bared teeth; some humans and animals have ribs clearly shown. All examples with teeth or ribs date within the last twelve hundred years. In the same region are also occasional rock art portrayals of human and animal figures with teeth and ribs. McClure (1984) argues convincingly that these rock art depictions date to the same time period as the carved portable objects. Finally, at an occupation site in southern British Columbia, a small, cylindrical stone painted with red dots and lines was recovered from a context more than two thousand years old (Copp 1980). The designs would fit in any of the area’s pictographs, indicating that simple geometric paintings are of considerable age in the region.

Portrayal of Datable Objects

Rock art from the northern Great Plains region of Alberta, Canada, Montana, and South Dakota shows thousands of historic items, including horses, guns, wagons, European Americans, and buildings. Since the dates at which these objects were brought to the area are known, the rock art is dated to the same time period. Likewise, rock art on the north Pacific coast shows sailing ships that can be reliably dated to historic times.

On the Columbia Plateau, approximately thirty sites show examples of horses or mounted humans (Boreson 1976; McClure 1979a). The drawings include both pictographs and petroglyphs, and occur in all areas of the region. We can reliably date these depictions after about A.D. 1720, when horses were first introduced onto the Columbia Plateau by Indians who had obtained them from Spanish settlements in New Mexico (Haines 1938). A few sites also contain drawings of a gun, a European American, and brands that date to the historic period.

In addition to historic items shown in rock art, depicted atlatls (throwing sticks used to propel stone-tipped darts) and bows and arrows are reliable time markers. The bow and arrow was first introduced onto the Columbia Plateau between two and three thousand years ago; before that, hunting weaponry was the spear or atlatl and dart. Atlatls are shown occasionally in rock art throughout the western United States. On the Columbia Plateau, probable atlatl depictions occur at petroglyph sites near The Dalles and on the Snake River south of Lewiston, Idaho. These panels were probably carved before the Indians acquired the bow and arrow. On the other hand, bows and arrows are relatively common, both as petroglyphs and pictographs, throughout the Columbia Plateau, occurring at sites in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. These designs must date within the last two thousand years.

Superimpositions

Occasionally one design will be carved or painted over another; thus superimposed, the overlapping figure must have been made more recently than the original. A series of superimpositions, involving stylistically distinct examples, can be useful in developing a generalized chronology for a region’s rock art, since the relative ages of each style can be shown. In some areas of the world (e.g., Valcamonica, Italy; Dinwoody, Wyoming; Coso Range, California), frequent superimpositions characterize rock art, and relative chronologies have been developed from detailed analysis of many instances of superimpositioning.

In Columbia Plateau rock art superimpositions are rare, although they occur occasionally in some parts of the region, most frequently along the middle and lower Columbia River. However, despite some tantalizing clues, we have not yet recognized a clear pattern of any specific design or style overlapping another. Instead, it appears that in this area a few superimpositions were done during approximately the past thousand years in a seemingly random pattern. Possibly further study will yield information that is of more value for turning these clues into a relative chronology.

Patination

Many petroglyphs along the middle Columbia River and the lower Snake River were made by pecking through the dark patina on the basalt bedrock characteristic of these areas. This patina, sometimes called desert varnish, is a brown to black stain that colors exposed rock surfaces. It occurs most often on stones in hot, arid portions of the world. Some scientists suggest that this patina forms due to chemical weathering and leaching of iron and manganese oxides from the stone, while others hypothesize that airborne microorganisms oxidize these minerals and concentrate them on the rock surface. In either case, the process is a slow one and desert varnish takes considerable time to develop.

When a petroglyph is pecked or carved through the patina on a rock surface, it exposes the lighter colored interior stone and creates a negative image, with the paler petroglyph showing on an otherwise dark background. If conditions for patina development still exist after the petroglyph is made, the newly exposed surfaces gradually begin to acquire the desert varnish. After a long period the design will be repatinated; it will have essentially the same patina as the unaltered rock face. Although repatination of petroglyph designs does not provide an absolute age (since exposure, temperature, humidity, and other factors influence the rate of patina formation), petroglyphs repatinating differently on the same surface are useful for creating a relative chronology. In such cases, those that appear fresher are younger than those that have repatinated to an appearance closer to the original surface of the stone.

Differential patination has been used on petroglyphs near The Dalles and at Buffalo Eddy on the Snake River south of Lewiston, Idaho, to suggest relative chronologies. At The Dalles, petroglyphs in the pit and groove style invariably are heavily patinated and weathered. At two sites, these contrast with much fresher appearing designs pecked at a later time. The heavy repatination of all of these pit and groove petroglyphs is consistent with that noted in the Great Basin area of Utah, Nevada, and California. There the appearance of this art style has been dated between five and seven thousand years ago. While we cannot automatically assign an equally ancient age to the pit and groove petroglyphs at The Dalles, certainly they are the oldest in this locale.

At Buffalo Eddy, Nesbitt described two rock art styles (1968). A naturalistic style shows primarily mountain sheep, deer, and humans wearing horned headdresses, while a “graphic” style is composed of triangles, circles, dots, and lines arranged in geometric patterns. At Buffalo Eddy, the naturalistic petroglyphs are usually repatinated, some very heavily. In contrast, the graphic designs are reported as fresher looking and cut through the patina on the rock surface. In one instance graphic style designs may actually be superimposed on repatinated naturalistic designs. In this case, the naturalistic drawings of men and mountain sheep clearly seem older than the graphic geometric designs.

Weathering

Variations in the weathering of different designs are often used in conjunction with patination studies, but such variations can also be applied to pictographs, which are not affected by patination. Many Columbia Plateau pictographs show weathering differences: some designs at a site will be very “fresh” looking while others will appear somewhat faded or will be partially covered by mineral deposits. Since different artists likely used paints of slightly different composition and color, differential weathering of pictographs is not as reliable an indicator of the passage of time as is differential patination of petroglyphs, but it does serve to indicate that paintings were made at different times.

The lack of evidence of extensive pictograph weathering during the last century also provides a dating clue by suggesting that some of these paintings could be of considerable age. Photographs taken of the Painted Rocks pictograph site on Flathead Lake in western Montana show the paintings to appear as fresh today as they did in 1903. With such minimal weathering, these (and other similar) paintings could be as much as several centuries old.

A Word Regarding Interpretation

Scientifically accurate interpretations of Columbia Plateau rock art are notably scarce. The written material that presents a realistic idea of the richness of this art tradition (and of the cultures of the artists), along with reasonable explanations of some of the reasons why the art was created, consists of a small handful of professionally published journal articles and graduate student research papers. None of these attempts to deal with more than a small part of the Columbia Plateau province, and very few are oriented toward helping the public understand and appreciate this rock art.

This lack of a comprehensive publication describing and interpreting rock art for the lay public is due primarily to scholars’ reluctance to speculate in print about their subject beyond the limits of statistical confidence intervals, competing hypotheses, and regional style definitions. Thus, the only interpretation readily available to the public often consists of far-fetched “translations” of sites or designs—some of which even go so far as to attribute this art to ancient Chinese explorers, lost Celtic monks, or prehistoric spacemen! The result is a dearth of interesting, scientifically accurate information about rock art written for lay readers.

Elsewhere, other authors and I (Dewdney 1964; Hill and Hill 1974; Joyer 1990; Keyser 1990) have shown that rock art can be interpreted for the general public in a way that both educates and entertains, while still observing the basics of scientific accuracy. Throughout this book I continue this effort. In some cases this involves making leaps of faith (albeit minor ones) that a strict scientific treatment would not. For instance, paintings of horsemen or groups of men with bows and arrows found in the extreme eastern part of the Columbia Plateau (in British Columbia and central Idaho) cannot be positively identified as depicting successful raiding parties returning from the northern Plains. No site was so identified by any of the Kutenai, Nez Perce, or Flathead Indian informants used by early ethnographers in the area. These Indians did, however, recall such raids on Blackfeet, Crow, and Cheyenne villages, and among the Nez Perce there are ledger drawings of such war parties. Informants also indicated that important events were sometimes pictured in rock art.

Therefore, putting these three things together—informant recollections of raiding parties, informant indications that important events were recorded in rock art, and the presence of rock art sites showing armed warriors or groups of horsemen—I feel comfortable speculating that some of these sites do, in fact, show war parties going to or returning from raids on Great Plains tribes. Similarly, the identification of bison hunt drawings, “twin” figures, “spirit beings,” and vision quest pictographs is based on logical deductions drawn from ethnographic accounts, comparison with rock art in other areas (world-wide), and my own experience in nearly twenty years of rock art research. Obviously, in a courtroom much of this would be circumstantial evidence and hearsay, but this is usually the only sort of evidence available to archaeologists. It is exactly this circumstantial evidence that enables us to tell the stories about the people who made the artifacts or painted the pictographs!

This book is, therefore, my interpretation and retelling of some of the myriad fascinating stories with which archaeologists entertain one another around field campfires or in the bars at professional conferences. As such, some of these deductions are not “statistically significant,” and some have alternate explanations in the form of “competing hypotheses.” They are, however, good stories, based on the best available scientific information and thousands of hours of analysis, study, and thought. I hope they make you think about the subject, but more than that, I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I enjoyed writing them.

† Long Narrows was the term for part of The Dalles of the Columbia River. A series of basalt gorges formed steep-sided canyons through which the Columbia cascaded; these are now obliterated by the Dalles Dam.

Map 2. The geographical boundary of the Columbia Plateau, which consists of the drainages of the Fraser and Columbia rivers and the Hells Canyon portion of the Snake River.