Читать книгу Blackfire - James Daniel Eckblad - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

~one~

ОглавлениеElli Adams lived as if she were always leaving, and people who are leaving are always different from those who aren’t, and so different from virtually everyone else. It wasn’t that Elli Adams wanted to leave, or had to leave, or even that she knew she was leaving. No, it was simply that she felt she was going to be leaving—whether she wanted to or not, and she didn’t know why. Maybe that was why she was so different from the other children—and why they knew she was different. Or maybe it was simply the “separation” issues that attend many children who, like Elli, are adopted.

But, actually, Elli did have to leave—she needed to be at the library—there was a book she wanted to read, and she was hoping they might have it. It was a book of poetry. Elli loved poetry. None of the other kids in school did. And those few who knew she liked poetry would tease her about it. But, then, most kids teased her anyway—if you could call it teasing. It wasn’t funny—at least, not to her. And it wasn’t actually funny to them either, even though they laughed. It simply gave them pleasure to say unkind things to her. But to her, it was like having hyenas gnawing at her back. Wherever she went it seemed there were boys and girls waiting to say unkind words to her as she walked by.

It was certain to happen again as she made her way to the library today. It was Saturday, and there would be lots of kids from school hanging out on the sidewalks. But she was willing to pay the price for another book of poetry. She loved poetry—and she loved poetry because of what it did to her small and confining world in Millerton; poetry took the small, ordinary parts of her every day life and transformed them into something extraordinary—not just seemingly extraordinary, but truly extraordinary. Because poetry took the individual, specific aspects of her ordinary, mundane world and made them into something that was true for the whole world: poetry about a brook, for example, that transformed it—and so the tiny river in town—into the journey that is all of life—transforming the particularly small into the universally large. Perhaps it was, as her adoptive mother alleged, with a tone of disapproval, a form of escape. But if it was a kind of escape, it was only because it allowed her to leave a small world for a much larger one.

Elli walked around the corner toward the library that was three blocks away. She was relieved to see there were no kids on the street. But she had walked only half a block when five or six kids appeared quite suddenly from a doorway across the street—and crossed the street behind her and began to taunt her. “Hey moon-face! Any astronauts land by mistake? Or just asteroids?” And then they laughed. The kids called her moon-face because of the pockmarks or “craters” that a serious bout of the chicken pox had left behind. She didn’t say anything. It only made them tease her more. So, with tears welling, but Elli not daring to let them fall, she continued her journey to the library. It was about the time when she could no longer hear what the kids were saying that she at last reached the large, double bronze doors of the old stone building.

Under vaulted ceilings with low-hanging fluorescent lights, Elli ran a fast check with the computer catalogue and then walked with confidence toward the circulation desk, as if she and the floor beneath her were bosom buddies. She was only 14 years old, but she had had her own library card for nearly 8 years, and she and the librarian, Ms. Simonson, had become good friends. Indeed, there was no place she liked to be more than at the library, and especially when Ms. Simonson and she would sit at the reference desk during slow periods on Saturday afternoons and talk about poetry and literature. She thought it odd that Ms. Simonson was not at the reference desk—and surprised to see a new face at the circulation desk.

“Yes, dear?” the desk clerk inquired.

“I’m looking for a certain book of poetry,” she replied.

“Have you checked the computer catalogue to see if we have it?”

“Umm . . . Yes, I did. But that’s the thing. It said you have the book, and that it’s not checked out, but I couldn’t find it on the shelves. In fact, I didn’t see any poetry on the shelves at all.”

“Oh, that’s right. The new Library Board instructed us to put all of the poetry downstairs to make more room for the expanding technology section. It seems no one checks out the poetry any more.”

“But I do, and I would very much like to check out this particular book. Could someone please find it for me?” Elli asked, as she laid a tiny scrap of paper with scribbling on it in front of the woman.

“I’m afraid I’m the only one at the circulation desk today—perhaps if you came back on Monday someone could help you then.”

“Oh, but I so very much would like to have it today. Will Ms. Simonson be here in a bit? I think she would be willing to help me.”

“I’m afraid Ms. Simonson is no longer with us; the board ordered staffing cuts this past week—and I was hired just two days ago to manage the library on Saturdays. I’ve never worked in a library before young lady, and I’m still trying to learn the procedures. Again, I’m sure someone will be able to help you on Monday.”

Elli heard nothing of what the woman said beyond her saying that Ms. Simonson was gone. Forgetting about the book momentarily, she asked, “How soon will there be a replacement for her?”

“My understanding is there will be no replacement, and that they plan to hire out the management of the library to an operations management company.” She added, as if she were signaling sudden expertise in the area of concern, “There is really very little need for librarians any longer, now that we have the Internet.”

Elli had no idea what the woman could possibly have meant by the remark, and considered it useless to carry the conversation any further. “Would it be possible for me to go downstairs and find it myself? I could spot it easily, I know, and it would only . . .”

“Young lady,” the woman interrupted, seeing that a small line had now formed behind Elli, “I can’t be of any help to you today. You will simply have to return on Monday when someone else besides me will be here. Now,” she added quickly, looking at the man who was behind Elli, “may I help you?”

The man actually reached over Elli’s head and put his books on the desk in front or her. Elli slipped aside to let the man get to the counter. She simply stood there and wondered: why couldn’t she herself go to the basement? That was what she was trying to ask the woman at the desk, but she was never given the chance. She thought to herself, “No one told me I couldn’t go to the basement!”

Elli glanced about the large reading room and noticed to her delight that what appeared to be the door to the basement was not only not behind the circulation desk, but was also open—as if it had been opened just for her, she pretended. Actually, the dark, oak paneled door, just around the corner behind the drop-off counter, wasn’t open very far—just an inch or so, as if someone had intended to close it, but had forgotten to make sure it was closed tightly—or had shut it, but, like many older doors, it just opened by itself. The bright light from the reading room poked through the partially opened door, allowing Elli to see that just to the other side was a flight of stairs—going down.

That had to be it, she thought. But maybe she’d better try to ask permission again before going any further. Elli moved a little closer to the front of the line where she had just surrendered her position to the man whom the woman was now helping. The woman’s eyes caught Elli’s and, sensing that Elli was not going to give up her quest just yet, she glared at Elli with a look that said, “I am not going to talk about this anymore.” And with that, as if sensing Elli’s thoughts, the woman, while walking past the basement door with a stack of return books, pushed hard on the door to make it shut, as if by the slam she was announcing both her authority and a final decision. She followed this with a dismissive look that was enough to persuade Elli to try to find the book on her own. When the woman returned to the circulation desk, Elli caught her eyes, stepped out of line and then headed straight for the bronze doors through which she had entered the building only minutes earlier, hoping the woman would think she was leaving.

When Elli was about four feet from the exit, however, she began to turn ever so slightly to her left—while looking back and giving a furtive glance toward the woman at the desk. When Elli saw that the woman was fully occupied with another young girl, she turned and headed back into the library around the many tall shelves of books, as if she had been the hand of a clock that had moved suddenly counterclockwise from twelve o’clock to nine o’clock, and then to five o’clock, where she located the basement door just twenty feet ahead of her. She could see, peeping above a row of books from the end of a shelf, that the woman at the desk was still occupied. But it was also apparent that Elli would be in her peripheral line of vision were she to make a dash for the door. Elli waited for just the right moment. The woman turned, as if suddenly ordered to do so by a commanding officer in an army, and began walking quickly in the direction of Elli, causing Elli to wonder if she had been discovered. But then, as if suddenly remembering she had forgotten something, the woman turned abruptly on one heel back toward the desk. Elli realized instantly that this was her best and perhaps only opportunity, and made a quiet dash for the door.

Elli tried the knob and found the door locked. She looked for a key and found a rather large and old one on a nail next to the door. She grabbed the chain holding the black skeleton key, unlocked the door and then slipped inside, shutting the door ever so gently behind her.

The head of the stairs she had noticed earlier through the slightly opened door was no longer in sight, and she was standing in pitch-black darkness.

Elli stood still in the small space, not wanting to fall down the stairs, and groped the three close walls enveloping her for a light switch. Like a blind woman trying to “see” another’s face with her hands, Elli let her probing fingers dance lightly over the surfaces of the cracked plaster walls, not wanting to miss the one spot where the switch was located. She found nothing. Perhaps it was a bulb with a switch or pull chain hanging from the ceiling. Elli stood on her toes and waved an arm throughout the impenetrable darkness while she leaned against one wall and then another to keep from falling. Still nothing.

All of a sudden, Elli heard the sound of the heels worn by the acting librarian. They were getting louder—and closer. Elli had to decide either to open the door and disclose her presence or, still in the dark, to lock the door and go quickly down the stairs. With little time for consideration, Elli locked the dead bolt and then groped for the handrail she had discovered in her search for a light. She found it and began an initially swift, but careful, descent. Elli descended no more than a few steps when she heard the knob jiggle, indicating, apparently to the woman’s satisfaction, that the door was locked as she had intended it to be. Elli then heard the heels walk away, as if in victory.

Elli assumed that the bottom of the stairs must be near, and that surely there she would discover a light switch. However, the handrail suddenly disappeared and the steps turned abruptly into stairs of stone that spread themselves like an unfolding fan into an ever-widening spiral. It was, she felt, as if she were a young woman in a wide skirted gown slowly descending the staircase of an elegant mansion to join her waiting escort.

Elli continued her descent on the stairs that, to her astonishment, seemed to have no end, and on a spiral that seemed ever to widen, as if the spiral staircase never intended to reach any sort of ground or pavement whatsoever, but simply existed for its own sake. She balanced herself against the stone wall as she stepped, careful with each footfall to make certain there was always another step or, better, a landing. To be sure to not lose the key, Elli placed the chain about her neck, tucking the key inside her shirt.

“Surely,” thought Elli, “I must have made a mistake—this couldn’t possibly be the stairs to the basement!” Elli stopped and turned, paused for an indecisive moment, and then began walking back up the stairs. But as soon as she began her ascent, Elli heard a door open just several feet below, and the bluish light from the doorway cast a large shadow of her small body on the stairs above her. Elli stopped, startled, and was about to run the rest of the way up the stairs when the voice of what had to be that of a very old man said to her kindly,

“Now, young lady, why would you be leaving when you are almost to the book?”

Elli, more puzzled than frightened, but duly fearful, too, turned toward the door that had opened from the wall only five steps below her, but with the stairway itself still continuing to descend into the darkness beyond the light. She could not see the man, but she could see through the doorway rows of dark wooden bookcases containing what she thought must be hundreds, if not thousands, of old books. The musty odors drifting onto the staircase made her think of what she guessed to be the scent of old monasteries, their libraries filled with devoted scribes and scholars laboring with ideas and words that mattered.

“Hello?” said Elli, as if not quite certain she was saying it to anyone there at all.

“Come in, come in,” the man said with quiet enthusiasm, as if he had been expecting her for hours, or days, or even a much longer time, ago.

With tentative steps and ready to turn and run if required, Elli descended the stairs to the doorway and stood there, looking in. She still saw no one—just a narrow, but deep, room with a number of bookcases that seemed endless in their length.

“Hello?” she asked again.

“Come in, come in!”

Elli took one step into the room and noticed immediately a small man sitting at a very small wooden desk, his face bent over a large old book, the pages of which appeared to have been turned many times over the course of many years.

The man turned a page and then spun around in his chair to look at Elli over a pair of tiny horn-rimmed spectacles. The man, who she judged could not have been more than three feet in height, nor less than a hundred years of age, was dressed in a brown, threadbare robe that was tied at the waist, not unlike those worn by monks she had seen in pictures. And he had a very large head on top of which rested a rather precariously tilted tall, pointed hat. His face reminded Elli of the faces often depicted as those of the man in the moon. He had a wide mouth, a small pug nose, bulging cheeks, and long, half-closed eyes, except that his cheeks and mouth were scrunched toward the center of his face, as if the hands of an unseen mother were pushing them together out of anger at her child. He wore brown leather boots with a metal hook on the top of each upper sole.

The man jumped from his chair, held out a hand for Elli to shake, and said, “I’m Peterwinkle, and I understand that you are looking for a certain book of poetry.”

“Ye . . . yes,” Elli replied, with surprise in her voice. “But how did you know, Mr. . . . Mr. Peterwinkle?”

“No, no . . . it’s not Mr. or Winkle or Peter, just Peterwinkle—all one word! Please, just call me Peterwinkle,” he said politely, so as not to seem scolding toward Elli.

“So, Peterwinkle, how did you know I was looking for a book of poetry? Did the woman at the circulation desk tell you I might be coming, and is she angry with me? And are you angry with me?” Elli asked.

“Oh, heavens no, dear girl! No one is angry with you—at least,” he added soberly, with a faraway look in his eyes, “not at this moment.” And he smiled.

Eager to obtain the book and be on her way, Elli said, “I’m looking for a book by an Adams, entitled . . .”

“Yes,” interrupted Peterwinkle, “I know the book. By ‘Adams,’ with no first name, and the title being simply Poetry.”

“Why yes! But, how did you know?” Elli asked, incredulously.

“It’s the only book of poetry that in all these years has never been checked out. And the only person wanting this book would be the only person to have found me. And so, here you are. And so you must be . . . ?” he asked.

“Elli Adams,” she replied.

“Precisely! Finally!” Peterwinkle said, with a controlled and uncertain gleefulness. “And,” he added, in a voice suggesting that he had almost forgotten the most important part, “it is dedicated to you, by one who will have written the book a very long time ago!”

“To me? . . . and ‘will have been written?’” Elli asked, with complete puzzlement.

“Yes, most definitely! It says: ‘To Elli Adams, without whose life this book could not have been written.’ Now, the only problem, dear girl, is that I don’t have the book at this time.”

“You mean someone else has checked it out? Or . . . it’s lost?!” Elli asked.

“No, no, Elli. None of that,” Peterwinkle assured her. “No one else has it, and it most definitely is not lost.” He paused to sigh deeply, and then he continued, “It’s just that the book has not been written yet, I’m afraid to tell you.” He paused again, and then said, “And, the only question is whether it will be written. I have, you see, the book, with its covers and pages, but there is nothing written on them except, as I said, the title, the author, and the dedication to you.”

“Well,” Elli said, “this is all so very confusing, Peterwinkle, and I’m disappointed that you don’t have the book and that, obviously, I’m simply wasting both your time and mine. So, thank you, and I’ll be on my way,” she said while turning to go.

“But, Elli,” Peterwinkle replied, almost matter-of-factly, “the book will only have been written if you provide the story for the poet.”

Elli turned abruptly back to face the little man. “You’re frightening me now, Peterwinkle, and I shall be going at once,” Elli said as she turned to leave once more.

“Of course I’m frightening you, dear girl! The world is a frightening place, as you well know, and it’s understandable that you should be frightened by me and all that I’ve said, but that doesn’t mean you have to run from that which frightens you.” Peterwinkle smiled kindly at Elli, and made no gesture to suggest he would physically discourage her from leaving.

“Please, come in, Elli, and at least have a cup of tea or lemonade with me, and let me try both to un-confuse you and to un-frighten you.”

Elli turned again, and Peterwinkle motioned toward a small chair next to his desk. Elli sat down, but with the open door in her peripheral vision, just in case.

“Now, Elli, let me tell you a brief story, the rather lengthy ending of which I will have to leave for another time together. Oh, would you like some tea or lemonade?” Elli shook her head slightly, as if not even hearing the question.

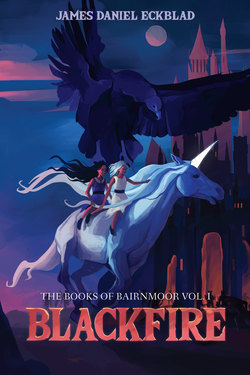

“A long time ago, there was a very grand and beautiful queen named Taralina who ruled the world of Bairnmoor, imbuing it with her love and kindness that became the source of all well-being and happiness throughout the land. She thought little of herself, except as an instrument of all that was good for her people. She desired nothing in return but the love and affection of her people, asking only that they also love each other in the same fashion that she loved them. Prosperity prevailed for all her people for thousands of years, and there was not one who did not enjoy the favor of her rule.

“But, there were a few of her subjects who wanted more, who became envious of her position and power, and who decided to rise up against her. Those who rose against her, whom we will call the ‘insurrectionists,’ knew she had no army—no real defense—except perhaps her stone castle that was built and used for benevolent, not defensive, purposes.

“Of course, the insurrectionists knew there would likely be many who would rally to her defense, but they were clever, and played upon the minds and emotions of the queen’s subjects, telling them that the queen was withholding from them much that they could yet enjoy. There would be larger plots of land, bigger homes, more impressive machines to assist them in their work, and greater freedom to do as they pleased, especially the freedom to rule themselves.

“There ensued a great battle, and many lives were lost on both sides, but in the end the insurrectionists prevailed and then enslaved virtually the entirety of the people, rewarding with wealth and privilege those who advanced the insurrectionists’ rule and punishing those who resisted with terrific poverty, imprisonment, torture, and death.

“The Queen, who was thought to possess enormous power from an unknown source, was easily locked away in the deepest regions beneath the castle, where to this day she remains. No one knows for certain what has happened to her, and the depths beneath the castle remain closed, with the Queen in a locked chamber and the most horrible of creatures guarding both castle and chamber beneath. It is said that another must release her for her power to return and defeat her enemies, taking control once again of the land—and this time ruling forever.

“It is further said, as has been said for centuries, that there is one who is to come who is alone able to release the Queen and who must do so before the insurrectionists have destroyed both the land of Bairnmoor and your world, Elli, sending both into the nothingness from which they can never return. So you see, the world in which you now live is entirely dependent on the world of Bairnmoor for its own continued existence, so that it is not only the future of Bairnmoor that hangs in the balance.

“It has been assumed that this one who is to come to release the Queen will have special powers that will enable that one to accomplish the mission that can be accomplished by no other—if, indeed, it can be accomplished at all. How, even with the greatest of powers, the Queen can be released, is unknown and incomprehensible for me to imagine. Yet there is one—and one alone—who is able to attempt the mission.”

It was not clear whether Peterwinkle had concluded his story. He glanced up at Elli and said nothing further. “Peterwinkle,” Elli said, after a lengthy pause, “I don’t know why you are telling me this story. I don’t even know, with all due respect, sir, whether I believe it or not. All I want is the book of poetry by Adams, and if it does not exist, then I should be on my way, although I am very pleased to have met you,” said Elli, as she straightened her shirt for departure.

“Oh, Elli,” replied Peterwinkle softly, “all of this has very much to do with you.”

“I should be going now,” Elli said curtly as she rose from the chair.

“Elli,” Peterwinkle said, with a deep longing in his eyes, “the Queen is depending on you.” He paused, and then added, looking imploringly into her eyes, “Everyone is.”

Elli sat back down, ever so reluctantly, overwhelmed in both her mind and her heart, her thoughts and her emotions, and with an emerging credulity for the story from which she wanted to flee with her entire being.

“Elli,” said Peterwinkle, as if the statement to be made was simply indisputable, “you are the one chosen to attempt this—yes, this incomprehensible—endeavor, and I am the one chosen to tell you so.”

“But, Peterwinkle, even if any of this—even if all of this—is true, the part that is otherwise false is that this Elli Adams is but a girl of fourteen, and I have no special or great powers whatsoever. So, there is a mistake—and probably someone else who is to come after me—and I am deeply sorry to tell you that, for I see that you have already concluded that I am this one you’ve been waiting for.”

“No, there is no mistake, Elli. You alone are the one to whom this book is dedicated; and the mere fact that you profess to no powers only confirms the veracity of your place in this business. Elli, it is not that you have great powers, but that you will have great powers in the undertaking of this mission. And you are not to do this alone. Indeed, you cannot do this alone. You will have companions to assist you, both from your world and from Bairnmoor, and without whom you would not be able to accomplish what is set before you—if it can be accomplished at all,” Peterwinkle added quickly, as if forgetting an obligatory phrase.

“But, who are these companions you speak about, Mr. Peterwinkle, and why do you continue to say that the mission may not succeed?” Elli asked, a bit perturbed.

“How can anyone assure the accomplishment of anything in the future, Elli? All that one can control is what one does, not the results. But, without your efforts, there is no hope—for any of us.”

“But, I must know, Mr. Peterwinkle: who are these companions of which you speak? Are they great adults, and is it they who will provide the great powers?” Elli asked, insistently, as if to create the answer to her question.

“Oh, Bumblesticks, no, Elli! You will have no adults with you. Only children. For only children will be able to enter the kingdom now, and only children will be able to save it.”

“Then, who are these children you speak of?” Elli asked, now pressingly. “I have very few friends, Peterwinkle, and I can think of none who would want—or be able—to accompany me, even if they believed the story was true.”

“Elli,” Peterwinkle giggled kindly, and then said, as if ignoring her doubts, “it will be three other children whom you most would trust to be without guile, to be loyal to your mission, and to protect your heart. It would be those who would say nothing false, and who would say nothing true they thought would injure you, and who would do all they could against others, regardless of the circumstances, who would seek to hurt you in any way. And,” Peterwinkle added, with a sense of prescient knowing, “I suspect that you know already about whom I am speaking. Am I correct?”

Reticent to speak, for any of a number of reasons pressing upon her mind and emotions, Elli simply nodded and said quietly, “Yes, I believe I do.” Peterwinkle sat silently, fingers folded together on his lap, waiting to hear more.

“There is Beatríz, also my age, who was born in Chile and,” she added, looking firmly into Peterwinkle’s eyes, “who has been blind since birth. And there is Jamie, who is a year younger than I and who comes from a really bad home and spends most of his time alone, with no self-confidence whatsoever—and other kids know it, so they tease him mercilessly, calling him weak and scared and good for nothing.” Elli paused, manifesting an appearance of general incredulity. “And, and . . . then there is Alex. Alex has Down syndrome, and is three years older than I. He’s in the same grade, but he has the mental capacity of someone younger than I. I eat and spend recess at school with these three, but, other than a couple of us occasionally meeting at the library, none of us spends time with any of the others outside of school; it’s safer that way. Guys who pick on us would be more inclined to get rough with several of us than with just one, if you know what I mean.” Peterwinkle nodded affirmatively.

“All of us like each other, and I can’t imagine that any one of us would say anything unkind about the others. I’m certain of that, since each of us has been hurt lots of times by others, and we all know how awful it feels.” Elli paused, and then said, conclusively, “I know of no others, among children or adults, to whom I’d trust my heart.”

Peterwinkle nodded his head approvingly. “I think you should be going—and then returning as quickly as you are able with your friends, for time is of the essence. You may, of course, decline to return, Elli, and you will not see or hear from me again. And no one but you and I and your friends will know of this conversation, and no one in either world will think more or less of you. Life will return for you as it has been, but with one exception. In this moment you have the opportunity that few in any world have, which is to find out who you really are. And the same may be said, I suspect, concerning your friends.”

Elli shivered at Peterwinkle’s final words and said nothing further. Exhausted in mind and heart, she mulled over all that Peterwinkle had said. She left the room, glanced furtively toward the wide staircase descending into the darkness below, and then carefully made her way back up the stairs and out the door, keeping the key with her.