Читать книгу I'll Bury My Dead - James Hadley Chase - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеI

T HE FOLLOWING MORNING, a few minutes to nine-thirty, Chuck Eagan drove the Cadillac into the circular drive leading to Julie’s Riverside apartment block, and pulled up outside the main entrance.

As he got out of the car, Nick English came through the revolving doors.

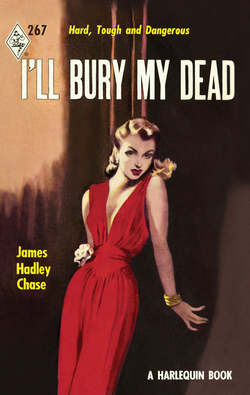

Chuck was wearing his favorite black suit, black slouch hat and white tie. This get-up, which Chuck regarded as the nearest to a uniform he would condescend to wear, set him off as a good frame can very often set off an indifferent picture. In a tuxedo he had looked like a third-rate waiter, but in this black lounge suit and slouch hat tilted over one eye at a jaunt angle, he looked what he was: hard, tough and dangerous.

“Morning, Chuck,” English said as he got into the car. “What’s the good word?”

“I went down and talked to the janitor like you said,” Chuck announced, leaning against the side of the car and looking down at English as he sank into the car seat. “A Joe named Tom Calhoun. He seemed a helpful sort of a guy after I had clinked some money by his ear. Your brother had a secretary. Her name’s Mary Savitt, and she’s got an apartment on 45th East Place.”

“Okay,” English said. “Let’s go there. Snap it up, Chuck. I want to catch her before she leaves.”

Chuck got into the Cadillac and set it in motion. While he drove rapidly through the traffic-congested streets, English glanced at the newspapers he had brought down with him.

All of them devoted considerable space to Roy’s suicide, coupling his name with Nick’s. At least Sam Crail had done a good job, English thought; there was no mention of Corrine. Morilli also appeared to be earning his keep. He had given out that Roy had been overworking, and it was believed he had shot himself in a fit of depression, following a nervous breakdown. The story sounded a little thin, but English was satisfied it would stand up so long as someone didn’t come along to challenge it.

Before leaving Julie’s apartment, English had called his office. Harry had told him newspaper reporters were at the office waiting for him, and he had told him to stall them until he arrived.

He wondered irritably if he were wasting his time going to see Mary Savitt. There was a lot to do. He had to see Senator Henry Beaumont and calm his fears. He had to have a word with the police commissioner. He had to talk to Sam Crail, and then there were the news hounds to deal with. But he was pretty sure if anyone knew why Roy had killed himself, this girl, Mary Savitt, would know. A private secretary had more opportunities than anyone to know the inside workings of her employer’s mind, and unless she was a feather-brain, she must have some idea what had gone wrong.

Chuck said, “Running up now, boss. This joint on the left.”

“Don’t stop at the door,” English said. “Drive on a half a block, and we’ll walk back.”

Chuck did as he was told, then stopped the car. The two men got out.

“You’d better come with me,” English said, and set off with long, quick strides to the brownstone apartment house Chuck had indicated.

A row of mail boxes in the lobby, each with the owner’s name on it, told English Mary Savitt’s apartment was on the third floor. The entrance to the apartments was guarded by a door by which was a row of buzzers. Chuck thumbed the third-floor buzzer, and waited for the latch to click up. Nothing happened, and after pressing the buzzer three times, he looked over at English.

“I guess the nest’s empty,” he said.

“She’s probably seen the newspapers and has gone down to the office,” English returned, frowning.

At this moment the door to the stairs opened and a girl came into the lobby. She was smartly dressed, and she looked sleepy and pale in the hard morning light. She stared at English, and her eyes opened wide. Her fingers went hastily to her hair, tucking in a stray curl under her hat. English watched her reaction indifferently. He had had his photograph so often in the newspapers, he had become used to being recognized by strangers.

He raised his hat.

“Pardon me, I was hoping to find Miss Savitt. She’s out, I guess?”

“Oh, no, she’s not out, Mr. English,” the girl said, smiling. “It is Mr. English, isn’t it?”

“That’s right,” English returned, holding his hat in his hand. “Clever of you to recognize me.”

“Oh, gee! I’d know you anywhere, Mr. English. I saw The Moon Rides High last week. I thought it was a terrific show.”

“I’m glad,” English said, and somehow he managed to convey that he was glad, and her opinion was something to cherish. “Maybe Miss Savitt’s still asleep. I’ve buzzed her three times.”

While he was speaking, Chuck was examining the girl with unconcealed interest. His sharp eyes admired her long, slim legs and he pursed his lips in a soundless whistle.

“Perhaps her buzzer’s on the blink,” the girl said, unaware of Chuck’s scrutiny. She had only eyes for English. “I know she’s in. Her milk’s still outside the door and her newspaper’s there, too. Besides, she never leaves before ten.”

“Then I guess I’ll go up and knock on the door,” English said. “Thank you for your help.”

“You’re welcome, I’m sure.”

He gave her a warm, friendly smile that left her looking a little dazed, and moved past her to the stairs, followed closely by Chuck.

As they walked up the stairs, Chuck said wistfully, “Brother! If only I could pull stuff like that. Did you see the way she looked at you—like jelly going into a faint! All you had to do was to snap your fingers, and she would have…”

“Cut it out!” English said curtly.

“Sure, boss,” Chuck said, rolling his eyes. As he climbed the stairs, his lips moved as he continued to talk silently to himself.

A bottle of milk and a folded newspaper lay outside Mary Savitt’s front door.

English jerked his head toward the door, and Chuck rapped sharply on it. No one answered. Again Chuck knocked, again no one answered.

“Think you could open the door, Chuck?” English asked, lowering his voice.

For a moment Chuck looked surprised, then he examined the lock.

“Nothing to it, but maybe she’ll squawk for the cops.”

“Go ahead and open it,” English said.

Chuck took out a small metal lever from his pocket, inserted it into the lock, fiddled for a moment, then pushed open the door.

English stepped into a neatly kept sitting room—small, well furnished and bright with spring flowers.

“Is anyone here?” he called, raising his voice.

He waited in silence, then crossed the room and knocked on a door facing him.

Chuck entered the room and quietly shut the front door.

English knocked again, then opened the door and looked into a darkened room. Enough light filtered through the drawn curtains to show him that it was a bedroom. He looked toward the bed; it was empty and the blankets were thrown back.

“I believe she’s out,” he said to Chuck.

“Maybe she’s having a bath,” Chuck said. “Want me to go and see?”

English ignored his eagerness and moved into the bedroom, turning on the light as he did so.

He came to an abrupt standstill.

To the right of the door leading into the bedroom was another door. Against this door, and hanging by a white silk cord which had been thrown over the top of the door and fastened to something on the other side, was the body of a dark-haired girl in her early twenties. She was wearing a white silk dressing gown that hung open to show a blue nylon nightdress. What beauty she might have had was spoilt now by her waxen color and her swollen tongue that protruded from her open mouth. Dried blood made a red thread from her nose to her chin.

Chuck drew in a sharp breath.

“Holy mackerel! What did she want to do that for?” he said in a tight, low voice.

English went over to her and touched her hand.

“She’s been dead about seven hours at a guess,” he said. “This is getting complicated, Chuck.”

Chuck came and stood at his side, his eyes appraising the dead girl.

“It sure is,” he said, then went on, “That’s exactly the kind of nightie I want my girl to wear, but she won’t wear anything but pyjamas.”

English wasn’t listening. He stood staring at the dead girl, his mind busy.

“We’d better get out of here, boss,” Chuck said after a long silence.

“Shut up, will you?” English snapped, and began to move around the room.

Chuck went over to the door and waited, his small, hard eyes on English.

“On the mantel, boss,” he said suddenly.

English looked at the mantel. Among the usual junk people keep on mantels was a silver-framed photograph of his brother Roy.

He picked it up.

Written in white ink across the lower part of the photograph in his brother’s big sprawling hand was the legend:

Look at me sometimes, darling, and remember what we’re going to be to each other. Roy.

English swore softly under his breath.

“So he had to fall in love with her!” He looked over at Chuck. “He’s certain to have written to her. His kind always does. Get busy and see if you can find any letters.”

Chuck went into action smoothly, quickly and with professional thoroughness.

English stood aside and watched him go through the various drawers and cupboards in the room. In a very short time Chuck had unearthed a packet of letters done up in blue ribbon which he handed to English, and then continued his search.

English glanced through the letters, recognizing his brother’s handwriting. He had only to read two or three of them to know that Roy and Mary had been passionately in love with each other, and that Roy had been planning to leave Corrine and go away with Mary.

With a wry grimace, he shoved the letters in his pocket as Chuck closed the last drawer.

“That’s the lot in here, boss.”

“Take a look in the other room,” English said, and when Chuck left the bedroom he picked up the framed photograph of his brother and dropped it into his pocket.

Five minutes later, English and Chuck left the apartment, went down the stairs and walked to the car.

“The office, and snap it up,” English said as he climbed into the car. “And keep your mouth shut about this, Chuck.”

Chuck inclined his head, slid under the steering wheel and sent the Cadillac shooting down the road.

II

The intercom on English’s vast mahogany desk buzzed into life, and reaching forward, he pressed down the switch.

“Mr. Crail is here, Mr. English,” Lois told him.

“Send him in, and when he’s gone, come in yourself,” English said, and pushed back his chair.

A moment later the door opened and Sam Crail came in.

Crail was nearly as tall as English, and immensely fat. His hair was black and thick and smoothly oiled. His complexion was pallid and his eyes sharp and beady. His smooth, fat jowls were blue with constant shaving, and his pudgy hands were hairy, his nails immaculately manicured.

Although his appearance wasn’t prepossessing, he was the smartest attorney in town, and had handled all English’s legal work ever since English had begun to climb.

“Hello, Nick,” he said as he pulled up a chair. “This is a bad business.”

English grunted, pushed his cigar box across the desk and eyed Crail speculatively.

“How’s Corrine?” he asked abruptly.

Crail grimaced. He selected a cigar, pierced it with a gold cigar pin, lit it and blew smoke to the ceiling.

“She’s difficult, Nick, and she’s going to make trouble.”

“No she isn’t,” English said shortly. “What do you imagine you’re on my payroll for? It’s your job to stop her making trouble.”

“What do you think I’ve been doing ever since I got there last night?” Crail said a little heatedly. “But she won’t play. Her story is Roy is in debt. He came to you for money, and you threw him out.”

English snorted.

“He came to me for a loan six months ago,” he said. “That’s not much of a story. Why didn’t he shoot himself sooner?”

“She maintains he came to you the day before yesterday.”

“Then she’s lying.”

“Roy told her he came to you.”

“Then he was lying.”

Crail examined the cigar thoughtfully.

“Might be difficult to prove, Nick. The press are only waiting for something to break. She says because you wouldn’t help him, he had to go to some of his old clients to raise the wind. One of them phoned the police. She says you told the police commissioner to withdraw Roy’s licence. With no future in front of him, he shot himself. Her story makes you directly responsible for his death.”

English frowned.

“Did Roy tell her this or is she making it up on her own initiative?”

“She says Roy told her, and that’s the story she’s going to tell the coroner. The inquest’s in an hour, Nick.”

“Yeah.” English stood up and paced over to the window. “She doesn’t like me, does she?”

“No, I guess she doesn’t. She says her life’s ruined, and she doesn’t see why yours shouldn’t be either.”

“The fool! Why does she think my life would be ruined by a yarn like this?” English said, turning from the window. “What put that idea into her empty head?”

Crail shrugged.

“It wouldn’t ruin you, Nick, but it would cause a stink. People think you are rolling in money. Public opinion is a dangerous thing to come up against. She says Roy wanted four thousand to get him out of his mess. Four thousand wouldn’t have scratched your pile. She could make it sound pretty sordid, Nick.”

“He wanted ten thousand and he wouldn’t tell me why,” English said. “I turned him down because I thought it was time he stopped sponging on me. He would have kept on and on if I hadn’t shown him he couldn’t come to me whenever he ran short of money. Look at the way he was living. He didn’t attempt to economize. Why the hell should I keep him and his wife?”

“Sure,” Crail said, “but now he’s shot himself, he gets the sympathy. This could put paid to the hospital idea, Nick. They are only waiting for an excuse to double-cross you.”

“I know.” English came back to the desk. “Now listen, the story is that Roy was overworking. The business was a disappointment. He tried to hold it together, but it was too much for him. Instead of coming to me, he tried to handle it himself, cracked under the strain and shot himself. That’s the story I’ve given the press this morning, and that’s the story you are going to give the coroner. Corrine will go with you and say ‘amen.’”

Crail looked startled.

“She won’t do it. I’ve talked to her, and I know. She’s made up her mind to be difficult.”

“She’ll do it,” English returned, his voice hardening. “If she doesn’t like that story, then I’ll give the press another she’ll like a lot less. Roy had a secretary; a girl named Mary Savitt. They were lovers. They planned to run away together, and leave Corrine out on a limb. Something went wrong; probably Roy couldn’t get enough money to quit. Being the weakling he was, he shot himself. The girl must have gone to the office and found him. She went home and hanged herself.”

Crail stared at him.

“Hanged herself?”

“Yes. I went to talk to her this morning, and found her dead. No one knows yet. Sooner or later they’ll find her, but I’m hoping the inquest will be over before they do.”

“Did anyone see you there?” Crail asked anxiously.

“I was seen going up the stairs. My story is I rang on the bell, and getting no answer, assumed she had gone down to the office.”

“Are you sure they were lovers?”

English opened a drawer, took out the photograph he had found in Mary Savitt’s bedroom and pushed it across the desk. He tossed the packet of letters into Crail’s lap.

“There’s all the proof. If Corrine thinks she can mess up my pitch by telling a snivelling yarn like this, she’s got another think coming. Tell her to toe the line or this muck goes to the press.”

Crail paused long enough to read two or three of the letters, then he put them in his briefcase, together with the photograph.

“This is going to be a shock to her, Nick,” he said slowly. “She was crazy about Roy.”

English regarded him, his eyes hard.

“She doesn’t have to know. That’s up to you. Persuade her to toe the line if you’re all that anxious to spare her feelings.”

“I guess she’ll have to see these letters,” Crail said. “All the same I don’t like it.”

“You don’t have to do the job,” English said. “I can always get another attorney, Sam.”

Crail shrugged his fat shoulders.

“Oh, I’ll do it,” he said. “I wouldn’t like to be as hard as you are, Nick.”

“Let’s skip the sentiment. Did Roy leave a will?”

“Yes. He left everything to Corrine. As far as I can see it amounts to a flock of debts. He had a safe deposit, and I hold the key. I haven’t had time to examine it, but I don’t reckon to find anything in it.”

“Let me know how his estate stands before you tell Corrine,” English said. “We could arrange to find an insurance policy in his safe deposit. Fix it that she has a couple of hundred bucks a week for life. I’ll pay.”

Crail grinned.

“Who’s going soft now?” he asked, getting to his feet.

“Get over to the coroner’s office,” English said curtly, “and make that story stand up.”

“I’ll make it stand up,” Crail said, nodded and crossed the room to the door. “I’ll call you as soon as it’s over.”

III

A minute or so after Crail had gone, Lois left her desk, crossed the room to English’s office door and tapped as she opened it.

English was staring at his cigar with cold, brooding eyes. He looked up and gave her a little nod.

“Come on in and sit down,” he said, and hunched his massive shoulders as he leaned across the desk. “What time did you get to bed this morning?”

Lois smiled as she pulled up a chair to the desk and sat down.

“It was after four, but I don’t need much sleep.”

“Nonsense. Of course you do. Go home after lunch and go to bed.”

“But really, Mr. English…” she began.

“That’s an order,” he broke in curtly. “Let the work wait. You’re always working. Let Harry do what’s necessary.”

“Harry was late, too,” she reminded him quietly. “It’s all right, Mr. English. I’m not a bit tired. We’re working on the fight figures.”

English ran his fingers through his dark hair and scowled.

“Damn it! I’d forgotten about the fight. What was the take?”

“Harry will have the figures for you in about half an hour.”

“Good. Now about last night. What did you think of the setup there?”

“Not much, Mr. English. I went through all the files. There’s been no new business since August.”

English frowned.

“Are you sure? Let’s see, I bought the business for him in March, didn’t I?”

“Yes, Mr. English. I’ve found correspondence dated up to July 31st, but nothing since then.”

“What was he doing then for the past nine months?”

Lois shook her head.

“The place might just as well have been closed. Nothing came in, and nothing went out. At least, there are no copies of letters in the files.”

English rubbed his jaw thoughtfully.

“How about his cases? Did he keep any record of those?”

“He handled eighteen cases from April to the end of July. Twelve of them were divorce cases, three missing people cases and three husband-and-wife watching. But after the end of July there are no records of him having any other cases.”

“What about his books?”

“There was a set in the safe. I took copies of the details from March to July. I thought the police mightn’t like it if I took the books away. I have the copies if you would like to see them.”

“What was his net average take?”

“Around seventy-five a week.”

English grimaced.

“That’s nothing. Did the books show anything after July?”

She shook her head.

“Then how in the world did he manage to run a house like that on seventy-five a week?” English said blankly. “You mean to tell me that since August the business hasn’t earned a dime?”

“He may have kept another set of books, Mr. English, but according to the one I found, nothing came in since August.”

English shrugged.

“Well, okay. What else did you find?”

“There was a card index holder in one of his desk drawers. It had a few blank cards in it. I have an idea the cards that were in use have been taken away.”

English studied her, his eyes interested.

“What makes you say that?”

“From the appearance of the box. The bottom of it was very dusty, and by the marks in the dust it was pretty obvious that there had been a number of cards in the box. I’m just making a guess, but it did strike me that a number of cards had been recently removed.”

“Maybe the box belonged to the previous owner.”

“It looked new to me, Mr. English.”

English pushed back his chair and stood up. He began to prowl around the office, his brows wrinkling into a frown.

“It’s damned funny, isn’t it?” he said after a long silence. “So no business at all was done in the office from August of last year to date. Is that right?”

“Yes, unless copies of letters and dossiers covering that period have been taken away.”

“Any sign of any paper having been burned in the office?”

“No.”

“Well, all right, Lois, thanks a lot. Sorry to have kept you out of bed so late. Be a good girl and go home after lunch. What’s important for me today?”

“You have two interviews this afternoon—Miss Nankin and Mr. Burnstein. You are lunching with the senator at one-thirty. There’s the mail and a number of contracts for your signature, and Harry would like you to see the balance sheet and figures of the fight.”

“Let’s have the mail first. Then send Harry in to me.” English glanced at his watch. “I have an hour and a half before I need worry about the senator.”

“Yes, Mr. English.”

She went out and returned almost immediately with the mail. She sat down at the desk with her notebook ready for his dictation.

Working with his usual speed, English polished off the mail, glanced through a number of contracts that had been initialled by Sam Crail, signed them, then pushed the pile of papers over to Lois.

“Let’s have Harry in now,” he said.

Harry Vince came in with slightly dragging feet. He looked pale, and there were smudges under his eyes.

English gave him a quick glance, then grinned.

“Late hours don’t seem to suit you, Harry,” he said. “You look like something the cat dragged in.”

“I guess I feel like it, too,” Harry said with a wan smile. “I have the figures for you. We have a net take of two hundred and seventy-five thousand.”

English nodded.

“That’s not so bad. Did you put a bet on Joey, Harry?”

Harry shook his head.

“I guess I forgot.”

English gave him a sharp look.

“What’s the matter with you? Don’t you want to pick up some free money? I told you you couldn’t go wrong.”

“I meant to, Mr. English,” Harry said, flushing, “but in the rush it went out of my mind.”

“Chuck made himself a thousand. Didn’t Lois back Joey?”

“I don’t think she did.”

“You two are hopeless,” English said with a resigned shrug. “Well, it’s your own funeral. I can’t do more than put the opportunity to make some money in front of you. That reminds me. Morilli will look in some time this morning. Give him three hundred out of my expense account. He’s supposed to have won it on the fight.”

“Yes, Mr. English.”

English stubbed out his cigar.

“Ever thought of getting married, Harry?” he asked abruptly.

Harry stiffened. His eyes shifted away from English.

“Why, no. I guess I haven’t.”

“Haven’t you even got a girl?” English asked, smiling.

“I just haven’t had time to get around to girls yet,” Harry said in a low, flat voice.

“Well, for God’s sake! You’re—what? Thirty-two or three?”

“Thirty-two.”

“You’d better buck up,” English said, and laughed. “Why, when I was half your age I had a string of girls.”

“Yes, Mr. English.”

“Maybe I’m working you too hard. Is that it?”

“Oh, no, Mr. English. Nothing like that.”

English stared at him, puzzled, then he shrugged.

“Well, it’s your life. Better send that balance sheet over to Asprey, and get him to certify it. I have a lunch date with the senator, worse luck.”

As Harry moved to the door, the buzzer on the desk sounded. English pressed down the switch.

“Lieutenant Morilli is here, Mr. English,” Lois said. “He would like a word.”

“Harry will see him,” English said. “I’m going to lunch.”

“He particularly wants to see you, Mr. English. He says it’s important and urgent.”

English hesitated, frowning.

“Okay, send him in. I’ve still got ten minutes. Tell Chuck to have the car ready.” As he released the switch, he said to Harry, “Get his money ready and give it to him as he goes out.”

“Yes, Mr. English,” Harry said and opened the door and stood aside to let Morilli enter the office.

“You’ve caught me at a bad time,” English said as Harry went out, shutting the door behind him. “I’ve got to go out in five minutes. What’s on your mind?”

“I thought I ought to have a word with you,” Morilli said, coming over to the desk. “We’ve located your brother’s secretary. A girl named Mary Savitt.”

English looked at him, his darkly tanned face expressionless.

“So what?”

“She’s dead.”

English frowned and stared at Morilli, who stared back at him.

“Dead? What—suicide?”

Morilli lifted his shoulders.

“That’s what I’ve come to see you about. It could be murder.”

IV

For a long second, English stared at Morilli, then waved him to a chair.

“Sit down, and let’s hear about it.”

Morilli sat down.

“I telephoned Mrs. English this morning,” he said, “to find out if Mr. English had a secretary. She gave me the girl’s name and address. I and a sergeant went down there. She has an apartment on 45th East Place.” He paused and looked hard at English.

“I know,” English said, taking his cue from Morilli’s look. “I went there myself this morning. I couldn’t get an answer. I thought she must have gone down to the office.”

Morilli nodded.

“That’s right,” he said. “Miss Hopper, who lives in the apartment above Miss Savitt’s, said she had seen you.”

“Well, go on,” English said curtly. “What happened?”

“We didn’t get an answer to our buzz. There was a bottle of milk and a newspaper outside the door, and that made me suspicious. We got a pass-key and found her hanging on the bathroom door.”

English pushed his cigar box across the desk after taking one himself.

“Go ahead and help yourself,” he said. “What’s this about murder?”

“On the face of it, it looked like suicide,” Morilli said. “The police surgeon said it was a typical suicide.” He rubbed his bony nose and added softly, “And he still thinks it’s suicide.” Then he went on. “After the body was removed, I had a look around the room. I was on my own, Mr. English, and I made a discovery. Near the bed was a damp patch on the carpet as if it had been recently washed. When I examined it carefully I found a small stain. I gave it a benzidine test. It was a bloodstain.”

English took his cigar from between his lips and frowned at the glowing end.

“I don’t reckon to be as smart as you, Lieutenant, but I fail to see how that makes it murder.”

Morilli smiled.

“A faked suicide is very often difficult to spot, Mr. English,” he said. “We’re trained to look for the giveaway. That stain on the carpet was a pretty complete giveaway. You see, when I cut the girl down I noticed she had bled from the nose. There were no marks on her nightdress, and I expected to find at least a drop or two of blood somewhere about her clothes. Then I find a stain on the floor. That tells me she died on the floor, and not hanging from the door.”

“You mean she was strangled on the floor?”

“That’s right. If someone surprised her, slipped the dressing-gown cord around her throat and tightened it she would have lost consciousness very quickly. She would have fallen face down on the carpet, and while the killer was exerting pressure on the cord, it is likely she would bleed from the nose, making a stain on the carpet. Having killed her, it would be simple for him to string her up against the bathroom door to give the appearance of suicide.”

English thought about this, then nodded.

“I guess that’s right. So you think it’s murder?”

“I won’t swear to it, but how else did the stain get on the carpet?”

“You’re sure it’s blood?”

“No doubt about it.”

English glanced at his wristwatch. He was already four minutes late for his appointment.

“Well, thanks for telling me, Lieutenant,” he said. “This is unexpected. I don’t know what to make of it. Maybe we can talk about it later on. Right now I have a date with the senator.” He got to his feet. “I’ve got to be running along.”

Morilli didn’t move. He sat looking up at English, an odd expression in his eyes that English didn’t like.

“What’s on your mind?” English asked curtly.

“It’s up to you, Mr. English, but I should have thought you would have wanted to settle this business right now. I haven’t put my report in yet, but I’ll have to within the next half-hour.”

English frowned.

“What’s your report got to do with me?”

“That’s for you to say,” Morilli returned carefully. “I like to help you where I can, Mr. English. You’ve always been pretty good to me.”

English had a sudden idea that there was something very wrong behind Morilli’s visit.

He leaned forward and flicked down the intercom switch.

“Lois? Get hold of the senator and tell him I’m going to be late. I shan’t be with him until two o’clock.”

“Yes, Mr. English.”

He released the switch and sat down again.

“Go ahead, Lieutenant. Do some talking,” he said, his voice hard and quiet.

Morilli hitched his chair forward, and looking English straight in the face, said, “I don’t have to tell you how the D.A. feels about Senator Beaumont. They’ve been sworn enemies ever since the senator got into office. If the D.A. can do anything to discredit the senator he’s going to do it. Everyone knows you’re behind the senator. If the D.A. can make things tough for you, he’ll do it in the hope it’ll eventually hit the senator. If he can involve you in a scandal, he’s not going to be too particular how he does it.”

“For a lieutenant of homicide, you keep remarkably well informed about politics,” English said. “All right, we’ll take that as read. What has it got to do with Mary Savitt?”

“It could have plenty to do with her,” Morilli said. “Doc Richards told me your brother died between nine and half past ten last night. He couldn’t put it nearer than that. He says Mary Savitt died between ten o’clock and midnight. Miss Hopper tells me she saw your brother leave Mary Savitt’s apartment at nine forty-five last night. It’s not going to take the D.A. long to arrive at the conclusion these two had a suicide pact. That your brother murdered the girl, then went down to his office and shot himself. If he does arrive at that conclusion there’s going to be quite a stink in the press, and it’s going to come this way and bound off you onto the senator.”

English sat still for a long moment, staring at Morilli, his eyes like granite.

“Why are you telling me all this, Lieutenant?” he asked at last.

Morilli lifted his shoulders; his small dark eyes shifted away from English’s face.

“No one but me knows it’s murder, Mr. English. Doc Richards says it’s suicide, but then he didn’t see the stain on the carpet. If he knew about that, he’d change his mind, but he doesn’t know, nor does the D.A.”

“But they’ll know when you’ve put in your report,” English said.

“I guess they will, unless I forget to mention the bloodstain.”

English studied Morilli’s white, expressionless face.

“There’s Miss Hopper’s evidence,” he said. “You say she saw Roy leave the apartment. If she starts talking, the D.A. will investigate. He might even find the stain.”

Morilli smiled.

“You don’t have to worry about Miss Hopper,” he said. “I’ve taken care of her. I happen to know what she does in her spare time. She wouldn’t want to go into the box and give evidence. Some smart attorney like Sam Crail might turn her inside out. I mentioned that fact to her. She isn’t going to talk.”

English leaned forward to knock ash off his cigar.

“You realize the chances are a hundred to one that Roy killed the girl, don’t you?” he said quietly. “If she was murdered, then someone is going to get away with it, if it wasn’t Roy.”

Morilli shrugged.

“It’ll be your brother who murdered her if the D.A. hears about the stain, Mr. English. You can bet your bottom dollar on it. Either way the killer gets away with it.” He made a little gesture with his hand. “It’s up to you. I’ll put the stain in my report on your say-so, but since you’ve taken care of me in the past, I thought it was only right I should give you a break when the chance came my way.”

English looked at him.

“That’s pretty nice of you, Lieutenant. I shan’t forget it. Maybe it would be better to forget about the stain.”

“Just as you say,” Morilli said, getting to his feet. “Only too glad to be of help, Mr. English.”

“Let me see,” English said absently, “you have a bet to collect, haven’t you? How much was it, Lieutenant?”

Morilli ran his thumbnail along his narrow, starkly black moustache before saying, “Five thousand, Mr. English.”

English smiled.

“Was it as much as that?”

“I guess that was the sum,” Morilli returned, his face expressionless.

“In that case I’d better pay you. I always believe in paying my debts.”

“I guess that’s right, and I always believe in giving value for money.”

“You would prefer cash I expect?”

“It would come in handy.”

English leaned forward and pushed down a switch on the intercom.

“Harry? Never mind about that little matter I mentioned to you just now. I’m looking after Lieutenant Morilli.”

“Yes, Mr. English.”

English released the switch, stood up and went over to the wall safe.

“You’ve a pretty good organization here, Mr. English,” Morilli said.

“Nice to know you approve,” English said dryly. He opened the safe and took out two bundles of notes and tossed them on the desk. “I won’t ask for a receipt.”

“You won’t need one,” Morilli returned, picked up the two bundles, checked the amount with a quick flick of his fingers and stowed them away in his overcoat pockets.

“Of course the D.A. might not trust your report,” English said, going back to the desk and sitting down. “He might send up one of his people to check the room, and he might find the stain.”

Morilli smiled.

“I like to kid myself that my service to you, Mr. English, is a pretty good one. The stain doesn’t exist anymore. I’ve fixed it.” He moved over to the door. “Well, I guess I mustn’t hold you up any longer. I’d better get over to the station house and write my report.”

“So long, Lieutenant,” English said. When Morilli had gone, English drew in a deep breath. “Well, I’ll be double damned!” he said softly. “The blackmailing sonofabitch!”

V

From the door of the restaurant, English spotted the senator sitting alone at a corner table, his thin elfish face puckered in a frown of impatience and irritation.

Senator Henry Beaumont was sixty-five years old, small, wiry and thin. His face was wrinkled and the color of old leather, and his eyes were steel-gray and as sharp as needles.

He was a man of insatiable ambition; his ultimate aim was to become president. He had started life washing bottles in a drug store, and he was inordinately proud of the fact. World War I had given him the chance he was looking for, and he proved himself an able leader of men, coming out of the Army with the rank of major and two minor decorations. By chance he had been taken up by the boss of the Democratic machine ruling Chicago at that time, and had been given the job of overseer of highways in recognition of his war service. It was while he was holding this appointment that he met Nick English, who was trying to finance his gyroscope compass. Beaumont introduced him to his circle of wealthy businessmen. It was through Beaumont’s introduction that English financed his compass.

When English finally settled in Essex City, he remembered Beaumont and wrote to him, offering to finance him if he cared to run for the post of county judge. Beaumont jumped at the offer, and with English’s money behind him, he was elected.

English was quick to realize that as his business expanded and his kingdom grew, it was essential to have a powerful friend in the political machine. Although Beaumont was no ball of fire, he was at least sharply aware of his debt to English, and was willing to pull strings when English wanted them pulled.

The next move, English had decided, was to get Beaumont elected senator. The opposition was stiff, but again with English’s money and coupled with his ruthless determination, Beaumont became senator. Now, he was to come up for reelection in another six months’ time, and English knew Beaumont was uneasy as to what the results would be.

The maître d’hôtel came hurrying over to English as he stood in the doorway, and deferentially led him down the long aisle to the senator’s table. As he followed the maître d’hôtel , English was aware that everyone in the luxury restaurant had stopped talking and was looking at him with curious eyes.

He was used to being stared at, but today he felt those stares were accentuated by something more than curiosity. The news of his brother’s suicide had caused a sensation, and people were already beginning to gossip about the reason for the suicide.

The senator half rose from his seat at English joined him.

“I thought you were never coming,” he said in his shrill, waspish voice.

English gave him a hard, cold look and sat down.

“I got held up,” he said shortly. “What are we going to eat?”

While the senator was choosing his meal, the maître d’hôtel slipped an envelope into English’s hand.

“This came for you about ten minutes ago, Mr. English,” he murmured.

English nodded, ordered a rare steak and green peas and half a bottle of claret, then ripped open the envelope and glanced at the scrawled message.

Everything under control. Corrine put on a beautiful performance. Verdict: suicide while mind was unbalanced. There’ll be no kickback.

Sam

English slipped the note into his pocket, a hard little smile lighting his face.

“What’s this I hear about your brother?” the senator asked as soon as the maître d’hôtel had gone away. “What the hell was he playing at?”

English looked at him, a surprised expression on his face.

“Roy’s been heading for a breakdown for weeks now,” he said quietly. “I warned him he was working too hard. Well, it got too much for him, and he took the easy way out.”

The senator snorted. His leathery complexion turned a dark red.

“Don’t feed me that crap!” he said fiercely, keeping his voice down. “Roy never did a hard day’s work in his life. What’s this about blackmail?”

English shrugged.

“There’s bound to be all kinds of rumors,” he said indifferently. “There are plenty of people who would like to make a stink out of it. You don’t have to get hot under the collar. Roy shot himself because he was worried about his business. That’s all there’s to it.”

“Is it?” Beaumont said, leaning forward to glare at English. “There’s talk he tried to blackmail some woman, and he was going to lose his licence. How true is that?”

“Every word of it,” English said, “but no one’s going to say so unless he wants a law suit with me about it.”

Beaumont blinked and sat back.

“Like that, is it?” he said, a look of admiration coming into his eyes.

English nodded.

“The police commissioner started this. I’ve had a word with him. He’s not taking it any further. You’ve got nothing to worry about, Beaumont.”