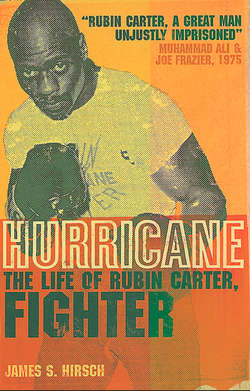

Читать книгу Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter - James Hirsch S. - Страница 10

5 FORCE OF NATURE

ОглавлениеTRENTON STATE PRISON did not tolerate dissidents. The gray maximum-security monolith ran according to an intractable set of rules that completely controlled its captives’ lives. Prison guards often said: “The state always wins,” meaning, rebellious prisoners ultimately comply. Rubin Carter would test that motto unlike any other inmate in New Jersey’s history. But opposition to authority was nothing new for him. It was, in fact, his nature.

Born on May 6, 1937, in the Passaic County town of Delawanna, Carter learned early on that the men in his family are not intimidated by threats. His father was one of thirteen brothers who all grew up on a cotton farm in Georgia. According to family lore, one brother, Marshall, was once seen fraternizing with a white woman. Panic surged through the house as word arrived that the Ku Klux Klan planned to crash the Carter home. The boys’ father, Thomas Carter, sent several of his sons to Philadelphia, instructing them to return with fifteen guns—one for each member of the family. The Klan arrived, but the Carters, fortified with weapons, stood their ground, and the hooded riders retreated. Shortly thereafter, the family packed up and moved to New Jersey—although each brother would return to Georgia to select a bride.

The Klan story, no doubt embellished over the years, impressed on Rubin the importance of family pride and unity. His father, Lloyd, also regaled his seven children with stories of tobacco-chewing crackers in the South hunting down black men, then tarring or hanging them. On cold nights at home, Lloyd Carter told these stories around a coal-stoked burner as his children ate roasted peanuts sent by relatives in the South. Rubin, in stocking feet, would stretch his legs toward the crackling stove and let his mind race through the Georgia swamps, chased by whooping rednecks and howling dogs. The specter scared him, but he felt protected by the closeness of his family.

When Rubin was six, the Carters moved to Paterson, to a stable, racially mixed neighborhood known as “up the hill”—a few blocks away from poorer residents, who were literally “down the hill.” Lloyd Carter made good money with his various business enterprises. He traded in for a new car every two or three years, and the Carters were the first black family in the neighborhood to own a television. But working two jobs six days a week—Sundays were for praying—wore him down, and his wife, Bertha, worried about his health. A lean, strong, bespectacled man just under six feet tall, Lloyd defended himself by quoting the Holy Scriptures. “Bert,” he said, “‘whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.’”

Lloyd Carter also disciplined his children with a religious zeal. A deacon in his Baptist church, he forbade the children from playing records or cards at home. Listening to the radio or dancing in the house was also prohibited. While he spoke softly, he carried a hard switch, and Rubin gave his father ample reason to use it.

The boy’s penchant for fighting often earned him swift punishment, but Rubin felt he had good reason to fight. He stuttered severely, stomping his foot on the ground to push the words out, and bitterly fought any kid who teased him for this impediment. His father had stammered as a youth, and his father had struck him with a calf’s kidney to try to cure him. Somehow Lloyd did overcome his speech problem, but he didn’t give his son much help. On the contrary, Rubin’s parents believed an old wives’ tale that severe stuttering indicated that the speaker was lying, which meant Rubin seemed unable to tell the truth. His response was to avoid talking, but that fueled the perception that he was stupid. To compensate for his stumbling tongue, the boy excelled in physical activities. He was muscular, fast, and fearless, and he saw himself as a protector of other people, particularly his siblings.

His brother Jimmy, for example, was two years older than Rubin, but he was studious, quiet, and prone to illness. When the Carters lived in Delawanna, Jimmy was sent to the basement to fetch coal from the family bin, but a neighborhood bully who was stealing the coal beat him up in the process. With his parents off at work, Rubin went to the basement himself to avenge the Carter name. It was his first fight. As he later wrote:

A shiver of fierce pleasure ran through me. It was not spiritual, this thing that I felt, but a physical sensation in the pit of my stomach that kept shooting upward through every nerve until I could clamp my teeth on it. Every time Bully made a wrong turn, I was right there to plant my fist in his mouth. After a few minutes of this treatment, the cellar became too hot for Bully to handle, and he made it out the door, smoking.

Bullies were not the only victims of Rubin’s wrath. In a Paterson grammar school, he once looked out his classroom door and saw a male teacher chasing his younger sister Rosalie down the hall. He raced out the door, tackled the teacher, and began swinging. The school expelled Rubin, prompting his father to beat him with a belt. But the beatings at home did not deter the boy, who continued to lash out at most anyone, even a black preacher who lived in the neighborhood. He owned a two-family home, and when he saw Rubin, at the age of ten, flirting with a girl who also lived in the house, he shooed him off the porch. But Rubin punched back with all his strength. The dazed preacher reported the incident to Rubin’s father, who stripped his son, tied him up, and whipped him.

Lloyd Carter feared that his son’s pugnacity would cost him his life one day, specifically at the hands of whites, and that fear led to a searing childhood incident. Each summer, Lloyd and his brothers drove their families in a caravan from New Jersey to Georgia, where they stayed with relatives, worked on farms, told stories, and sang and prayed together. On one occasion after church, some cotton farmers gathered in a grove to sing and picnic. A white man selling ice cream bars stopped nearby, and children carrying dimes raced to get a treat. Rubin had barely torn his wrapper when his father landed a heavy blow on his face, sending Rubin and the ice cream in opposite directions. Lloyd Carter never said why he struck his son; years later Rubin realized that his father feared white men, and he wanted his son to feel that same fright as well. Instead, the nine-year-old, his face puffed and bruised, came away with a very different lesson. He had taken his father’s best shot, and now he no longer feared the man. Moreover, Rubin determined that he was never going to let another person hurt him again. Not his father, not a police officer, not a prison guard, not a mayor, not a bum. Nobody.

Young Rubin welcomed any physical challenge—the more dangerous, the better. He swam in the swift waters of the Passaic River, jumped off half-built structures at construction sites, ran down mountains, and rode surly mules on his grandfather’s farm. On a swing set in the Newman playground, he swung so high that he flipped completely around in full circles. On one occasion, he and a friend, Ernest Hutchinson, were cutting through a backyard when a big bulldog ran at them. “I was going nuts, but Rubin told me to stand behind him,” Hutchinson recalled. “All of the sudden, the dog leaps and—bam!—Rubin hits him right in the chest. The dog rolled over and couldn’t catch his breath. I’ll never forget that. We were ten years old.”

Rubin continued to rebel against his father’s rules. Even on a simple walk to P.S. 6 on Carroll and Hamilton Streets in Paterson, he had to make his own way. Lloyd Carter stood on the porch of their Twelfth Avenue home and made sure all his children took the safest, most direct route. When the brood was out of his sight, Rubin ducked into an alley, hopped a fence, and took a different, longer way. He was literally incapable of following the crowd.

But misdeeds landed him in more serious trouble—with both his father and ultimately the police. Rubin stole vegetables from a garden owned by one of his father’s co-workers, ransacked parking meters, and led a neighborhood gang called the Apaches. When he was nine, the Apaches crashed a downtown marketplace, stealing shirts and sweaters from open racks, then fleeing to the hills. Rubin gave his stolen goods to his siblings. When his father saw the new clothes, price tags still attached, and was told that Rubin was responsible, he beat his son with a leather strap, then called the police. The boy was taken to headquarters—his first encounter with the police. He would always resent that his father had initiated what would become a lifelong battle with law enforcement officials. The following day, the Child Guidance Bureau placed him on two years’ probation for petty larceny.

For all the confrontations between father and son, Rubin noticed that he liked to do many of the same things as his father. While his two brothers and four sisters often begged off, Rubin hunted with his father and accompanied him on trips to the family farm in Monroeville, New Jersey. His mother told him that his father was hard on him because Lloyd himself had also been a rebel in his younger days. Now, the father saw himself in his youngest son.

That did not become clear to Rubin until he was in his twenties, when he and his father went to a bar in Paterson where the city’s best pool shooters played. As they walked in, the elder Carter quipped, “You can’t shoot pool.”

A challenge had been issued. Rubin considered himself an expert player, and he had never seen his father with a cue stick. Indeed, Lloyd hadn’t been on a table in twenty years. They played, betting a dollar a game, and Lloyd cleaned out his son’s wallet.

Rubin, shocked, simply watched. “Where did you learn to play?” he asked.

“How do you think I supported our family during the Depression?” his father replied. “I had to hustle.”

Unknown to his children, Lloyd Carter had been a pool shark, and his disclosure seemed to clear the air between him and Rubin. “Why do you think I always beat on you?” Lloyd said later that night. “You wouldn’t believe how many times your mother said, ‘Stop beating that boy, stop beating that boy.’ But I saw me in you.” Lloyd Carter had also rebelled against authority, and he knew that was a dangerous trait for a black man in America. “I was trying to get that out of you,” he told his son, “before it got hardened inside.”

It was too late, however. Rubin’s defiant core had already stiffened and solidified.

For all the turmoil in his youth, Carter actually fulfilled one of his boyhood dreams: he wanted to join the Army and become a paratrooper. In World War II the Airborne had pioneered the use of paratroopers in battle. It was not, however, the division’s legendary assaults behind enemy lines that captivated Carter. Nor was it the Airborne’s famed esprit de corps or its reputation for having the most daring men in the armed forces. Carter liked the uniforms. Even as a boy he had a keen eye for sharp clothing, and he admired the young men from Paterson who returned home wearing their snappy Airborne outfits: the regimental ropes, the jauntily creased cap, the sterling silver parachutist wings on the chest, the pant legs buoyantly fluffed out over spit-shined boots.

By the time Carter enlisted, however, the uniform was not his incentive. At seventeen, Carter escaped from Jamesburg State Home for Boys, where he had been serving a sentence for cutting a man with a bottle and stealing his watch. On the night of July 1, 1954, Carter and two confederates fled by breaking a window. They ran through dense woods, along dusty roads, and on hard pavement, evading farm dogs, briar patches, and highway patrol cars. Carter’s destination was Paterson, more than forty miles away. When he reached home, the soles on his shoes had worn off. His father retrofitted a fruit truck he owned with blankets, and Rubin hunkered down in the pulpy hideaway while detectives vainly searched the house for him. Soon Carter was shipped off to relatives in Philadelphia. He decided, ironically, that the best way for him to hide from the New Jersey law enforcement authorities was by joining the federal government—the armed forces. With his birth certificate in hand, he told a recruiting officer that he was born in New Jersey but had lived his whole life in Philly. No one ever checked, and Rubin Carter, teenage fugitive, was sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to learn to fight for his country.

Carter was no patriot, but soldiering allowed him to do what he did best: wield raw physical power. The Army, in some ways, was similar to Jamesburg, the youth reformatory. Carter lived in close quarters with a group of young men, and he was told what to do and when to do it. Individual opinions were forbidden; and just as a reformatory was supposed to correct a wayward youth, the Army was supposed to turn a civilian into a soldier. Carter spent eight grinding weeks in basic training, followed by eight more weeks to join the Airborne. He was then sent to Jump School in Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Recruits were known as “legs,” because graduates received their paratrooper boots. Each class began with about 500 would-be troopers; as few as 150 would graduate. The school’s relentless physical demands thinned the ranks, as recruits were eliminated by the early morning five-mile runs, the pushups on demand, the pullups, the situps, the expectation to run everywhere while on the base, even to the latrine.

Most difficult of all, however, trainees had to learn to leap twelve hundred feet from a C-119 Flying Boxcar. To prepare, they hung from the “nutcracker,” a leather harness suspended ten or fifteen feet aboveground. They lay on their backs strapped to an open parachute while huge fans blew them through piles of sharp gravel until they were able to deflate the chute and gain their footing. There was also the “rock pit.” Soldiers stood on an eight-foot platform, jumped into the air, and did a parachute-landing fall onto the jagged bed of rocks. They then got up and did it over and over again until ordered to stop. To quit was tempting, but the Army sergeants and corporals who ran the Jump School gave those who faltered a final dose of humiliation. They were forced to walk around the base with a sign on their shirt that read: “I am a quitter.”

To Carter, Jump School was “three torturous weeks of twenty-four-hour days of corrosive annoyance.” But when he executed his first jump, he excitedly wrote home about it, flush with pride, and later described the sensation.

There was no time for thought or hesitation. I could only hear the dragging gait of many feet as man after man shuffled up to the door and jumped, was pushed, or just plain fell out of the airplane. The icy winds ripped at my clothing, spinning me as I hit the cold back-blast from the engines, and then I was falling through a soft silky void of emptiness, counting as I fell: “Hup thousand—two thousand—three thousand—four thousand!” A sharp tug between my legs jerked me to a halt, stopping the count, and I found myself soaring upwards—caught in an air pocket, instead of falling. I looked up above me and saw that big, beautiful silk canopy in full blossom and I knew that everything was all right. The sensation that flooded my body was out of sight! I didn’t feel like I was falling at all; rather, the ground seemed to be rushing up to meet me.

The ground, however, gave Carter a jolt of reality. Even though the armed forces had officially been desegregated under President Truman, racial segregation and inequality still prevailed. Riding a train from Philadelphia to Columbia, South Carolina, black soldiers were shoehorned into the last two cars while whites rode in relative comfort in the first twenty-odd vehicles. When paratrooper trainees were bused from South Carolina to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, passing through Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, blacks sat in the back of the bus. At dinnertime, whites ate at steakhouses while blacks had to stay outside and eat cold baloney sandwiches and lukewarm coffee.

This experience pricked Carter’s racial consciousness for the first time. Whites and blacks had mixed easily in his old neighborhood in Paterson, and while Jamesburg State Home segregated the inmates, Carter assumed that whites slept in their own quarters because they were weaker than blacks and therefore vulnerable in fights. But as his bus rolled through mountainsides of quaking aspens, he saw white farmers guzzling beer at resting stops, their drunken rebel shrieks grating his nerves. Their pickup trucks carried mounted gun racks, and they eyed the black soldiers suspiciously. Carter suddenly realized why his father and uncles drove their families through the Deep South in caravan style. He had thought it reflected the family’s solidarity, but he now understood that it was to provide safety in numbers. He felt angry that his parents had not told him about the true dangers that lay across the land—in the South and throughout the country. This discovery came at the very moment Carter was training to fight for America. He decided from here on he would defend himself in the same fashion that he was defending his country—with guns. If his adversaries, be they communists or crackers, had weapons, so too would he. Carter kept these thoughts to himself, however. Speaking out was not his style. But his silence, about race and all other matters, would soon end.

By the time the winter winds blew through Fort Campbell in 1954, the 11th Airborne was preparing to transfer to Europe. Carter was one of three hundred paratroopers recruited from the States to be part of the advance party. Their destination: Augsburg, Germany. Founded almost two thousand years ago, Augsburg is one of those languorous Bavarian towns that lolls in the shadows of its history. Grand fountains and tree-shaded mansions with mosaic floors evoke a golden age of Renaissance splendor. In the Lower Town, among a network of canals and dim courtyards, small medieval buildings once housed weavers, gold-smiths, and other artisans. Nearby is Augsburg’s picturesque Fuggerei, the world’s oldest social housing project that still serves the needy. Built in 1519, it consists of gabled cottages along straight roads and preaches the maxim of self-help, human dignity, and thrift.

But Augsburg’s patrician munificence and cobblestone alleys were far removed from the fervid world of Private Rubin Carter. He spent most of his time on the Army base, a member of Dog Company in the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment. Each day began at 6 A.M. with an hour’s run on the cement roads surrounding the compound. Even on the coldest winter mornings, Dog Company ran in short-sleeve shirts, their frozen breath from shouted cadences hanging in the Augsburg air.

“Hup-Ho-o-Ladeeoooo!” the sergeant yelled.

“Hup-Ho-o-Ladeeoooo!” the Dog Company echoed.

“Some people say that a preacher don’t steal!”

“Hon-eee! Hon-eee!”

“Some people say that a preacher don’t steal—but I caught three in my cornfield!”

“Hon-eee-o Ba-aa-by Mine!”

Military maneuvers on the steep hills around Augsburg were a weekly exercise. The soldiers clambered up and down the slopes in leg-burning labors, firing blank bullets to secure a hill or to push back an imaginary enemy. But Carter learned what the real nemesis was on his first maneuver.

“Oh shit!” someone yelled. “It’s comrades’ ‘honey wagons.’”

A fetid smell swept across the hills. On nearby cropland, farmers took human excrement from outhouses, slopped it in honey wagons, and spread it across their potato and cabbage fields. There was no defense against this invasion, but Carter never complained. Shit, the stench inside prison is worse.

Carter attended daily military classes in the “war room,” where maps of the European terrain hung on the wall and the platoon’s weapons were stored. He studied heavy weapons, rifles, and mortars, memorizing their firepower. Carter trained as a machine gunner; his job would be to back up the front line.

He liked the rigors and responsibilities of Army life, but his early days in Augsburg were marked by isolation and loneliness. His stutter, as always, deterred him from reaching out to others. He was also afraid that the Army would discover the deceptive circumstances of his enlistment and that he was a wanted man in New Jersey. Best to keep a low profile, he figured. So he never spoke up in class, he ate alone in the mess hall, and he rarely socialized at the service club, where friendships were forged over watered-down beer and folds of cigarette smoke. On weekends, he took the military bus to Augsburg. The town had an aromatic blend of fresh bread, spicy bratwurst, and heavy beer, a piquant scent that would hang on the soldiers’ leather jackets long after they returned to the States. Augsburg’s horse-drawn wagons and pockmarked buildings from a 1944 air raid added to the town’s quaint and battered charm; but for most soldiers, its attractions were the liquor and the women. At one restaurant, each table was equipped with a telephone so that male patrons could ring nearby ladies of the evening and request a date.

Carter, however, rarely socialized and did not stray far from Augsburg’s Rathausplatz, the town square. He had no special interest in its statue of Caesar on an elaborate sixteenth-century fountain. He simply was afraid he would be stranded if he missed the bus home.

The Airborne troops conducted weekly practice jumps in a nearby drop zone. One morning, after falling from the sky, Carter was folding his parachute when he heard a strange voice from over his shoulder.

“How you doin’, little brother?”

Carter looked up but said nothing. A man he had never seen before had landed within twenty yards of him, but the close touchdown did not appear to be accidental.

“I’ve been watching you,” the strange man said, “and I think you’ve got a problem.”

“W-w-what’s that?” Carter demanded, stunned by the stranger’s effrontery.

“We’ll talk about that later,” the stranger said. “Let’s go back to the base.”

Ali Hasson Muhammad was unlike anyone Carter had ever met. A Sudanese Muslim, Hasson had immigrated to America and was now trying to earn early citizenship by serving in the Army. He wanted to give Carter guidance as much as friendship. With braided hair that wrapped around his head and a shaggy beard, he was like a sepia oracle. While other authority figures in Carter’s life—his father, reformatory wardens, Army sergeants—had lectured him, Hasson spoke in parables designed to redefine Carter as a black man.

Walking back to their barracks one night, Hasson told Carter how a fat countryman from Sudan fell asleep while shelling peas in the attic of his cramped hovel. “The hut mysteriously caught on fire, and the village people rushed in to save the farmer,” he said. “But they couldn’t do it, because the man was too fat and the attic too small to maneuver him over to the stairs. The townsmen worked desperately, but without success, to save the man before it was too late. Then the village wise man came upon the scene and said, ‘Wake him up! Wake him up and he’ll save himself!’ ”

Black Americans were also asleep, Hasson told Carter, and they would have to wake up to save themselves. Hasson was a slender man who spoke softly and worked as a clerk because he refused to carry a weapon. But his dark, glaring eyes conveyed the passion of his beliefs. “Nobody can beat the black man in fighting, or dancing, or singing,” he told Carter. “Nobody can outrun him or outwork him—as long as the black man puts his mind and soul to it.” Tears of frustration welled in Hasson’s eyes. “What on God’s earth ever gave the black man in America the stupid, insidious idea that white men could out-think him?”

Carter heard Hasson’s ardent pleas but never really absorbed them. What does this have to do with me? He didn’t understand some of Hasson’s more opaque sermons and euphemisms, and he had trouble believing Hasson’s thesis of black superiority. What evidence was there in his own life to prove such a claim?

The evidence soon surfaced a half mile from Carter’s barracks. The Army’s Augsburg fieldhouse, with a sloped quarter-mile track, a basketball court, and weight machines, was the social and athletic epicenter of the base. Even on nights when frost covered the ground, the creaking gym retained a muggy, pungent atmosphere from the men’s concentrated exertions.

Carter rarely entered the fieldhouse. But after pouring down a few too many beers at the service club one night, he and Hasson took a shortcut through the gym. There, they were stopped cold by what they saw—prizefighting. The 502nd regimental boxing team was in training, and the drills seemed to produce their own wonderful soundtrack: the staccato beat of speed bags, the plangent thuds of fists against heavy bags, the testosterone snorts of determined fighters. Carter and Hasson watched for a good while.

“Shit!” Carter said suddenly. “I-I-I can beat all these niggers.” Hasson looked at him in disdain. “I can see why you don’t open your mouth too much,” he said. “Every time you open it, you stick your foot right in it. So why don’t you just finish the job and tell that gentleman over there what you’ve just told me. Maybe he can straighten you out.”

Hasson motioned to a young, ruddy-faced coach named Robert Mullick, whose blond hair was sheared so short you could see the pink of his skull. His blue eyes sparkled as he reviewed the boxers working out. The boxing ring was the Army’s surrogate battlefield, where champions were wreathed in glory, and the boxing coach trained his men to show no mercy. “Lieutenant?” Hasson said, grinning. “My little buddy thinks he can fight. In fact, he honestly feels that he can take most of your boys right now. So he’s asked me to ask you if you could somehow give him a chance to try out for the team.”

Mullick looked over Hasson’s shoulder at Carter, who suddenly felt his silver parachutist wings hanging heavily on his shirt. Paratroopers were known as a cocky crew, often boasting that one of them could do the work of ten regular soldiers. They were also disliked for another reason: they received higher pay than the GIs, driving up the price of prostitutes.

Now Carter thought his parachutist wings were like a bull’s-eye, signaling to the grim lieutenant that this was his chance to teach at least one saucy trooper a lesson. “So, you really think you can fight, huh?” Mullick asked. “Or are you just drunk and you want to get your stupid brains knocked out? Is that what you want to have happen, soldier?”

Carter’s first reaction was to do what he always did when someone challenged him: knock him down, teach him some respect, show him he wasn’t to be meddled with. But he held back his fists if not his lip.

“I-I-I can fight—I can fight,” Carter stammered. “I’ll betcha on that.”

“You will?” Mullick said, a grin creasing his face. “Well, I’m going to give you a chance to do just that, but not tonight. You’ve been drinking, and I don’t want any of my boys to hurt you unnecessarily. Just leave your name and I’ll call you down tomorrow. Maybe by then you won’t think you’re so goddamn tough.” He turned his back to Carter; the conversation was over.

The next day Carter lay in bed, petrified. He had always been a streetfighter, and a good one at that. His gladiator skills had earned him the position of “war counselor,” or chief, of his childhood gang. War counselors negotiated the time and place of rumbles between gangs, but sometimes they agreed to fight it out between themselves. Carter always relied on “cocking a Sunday,” or slipping in a wrecking ball of a punch when his opponent wasn’t expecting it. He didn’t know how to move around a boxing ring, to counterpunch or to tie up, and his chances of cocking a Sunday on a skilled fighter seemed impossible.

But Mullick was not about to let Carter off the hook. His drunken challenge was a slur against Army boxers, and now he would pay for it. Through a company clerk, Mullick ordered Carter to report to the fieldhouse. When he arrived, the arena was abuzz. Prizefighting was a big sport in Germany, and the impending fight had attracted droves of Army personnel, including sportswriters from Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper. It seemed that the dismantling of a brassy parachute jumper would liven up an otherwise slow day in the Cold War.

Carter stood unnoticed in the doorway, watching two fighters in the ring hammer each other. The short dark fighter was bleeding from a gash over his eye. The other fighter seemed to be suffocating from his smashed nose, spitting out gobs of blood from his mutilated mouth. The crowd stood, cheered, roared for more mayhem, indifferent to who was winning or losing as long as someone toppled over. Carter knew he was out of his class.

When the bout was over, Mullick jumped down from the apron—he had officiated the fight—pushed through the crowd, and found Carter. “Are you ready for that workout now, mister?” Mullick asked. “Or do you have a hangover from boozing it up too much last night and want to call it off?” Carter shook his head.

The lieutenant nodded, wheeled around, and strode back toward the ring, where his fighters were clustered. Carter admired the sweaty black faces. They were scarred and ring battered, but they seemed to have a closeness about them that transcended their ebony surface. They were men of great courage, Carter thought. You’d have to shoot them to stop them, for their pride and integrity couldn’t be broken.

Finally, breaking away from the squad and climbing into the ring was a large boxer with a sculpted chest and stanchions for legs. He shook out his arms, flexed his ropy muscles, and shadowboxed in a glistening ritual. I have to admit, the nigger looks good, Carter thought.

The mob of spectators jumped to their feet and shouted their conqueror’s name. He was Nelson Glenn, six feet one inch of animal power, the All-Army heavyweight champ for the previous two years. Mullick climbed through the ropes and began lacing on his fighter’s gloves. At the same time, he motioned Carter to enter the ring. It was too late to back out, so he climbed in, Hasson on his heels.

Carter felt the adrenaline pump through his stout body and he showed no fear. He felt light on his feet but also strong, resolute. He was not going to flinch, to back down, to quit. He felt a sharp, electrifying twinge of self-respect. Nelson Glenn will have to bring ass to get ass. But he also felt the loneliness, the vulnerability, of the boxing ring. There was no escape.

Hasson tied on Carter’s liver-colored gloves and offered some counsel. “Stay down low, and watch out for his right hand,” he whispered softly. “And try to protect yourself at all times.” Carter nodded.

Mullick called both fighters to the center of the ring to explain the ground rules, but he spotted a problem with Carter. Like Glenn, Carter wore his standard green Army fatigues (long pants, shortsleeve shirt) and tight Army cap, but Mullick pointed to Carter’s shoes. “What are those?” he asked.

“My boots,” Carter said.

Mullick rolled his eyes. “What size shoe do you wear?” he asked.

“Eight and a half,” Carter responded.

“You need boxing shoes,” Mullick said, more in pity than disgust. He fetched a pair from one of his own boxers and Carter sheepishly made the switch. Now he was ready.

The bell rang.

Glenn came out dancing, jabbing, grunting, contemptuous of this no-brain, no-brand opponent who presumed to step into the ring with the champion. Carter tried to stay beneath his crisp left hand, pursuing his adversary like a cat in an alley fight. Carter bobbed, feinted, ducked, then lashed out with his first punch of the fight—a whizzing left hook that caught Glenn flush on his chin, spilling him to the canvas. The blow may have startled Carter as much as Glenn.

Glenn bounced up quickly but was now groggy. He was surprised by the power of a mere welterweight. Carter returned to the attack and bored in with a quick, crunching left hook, then another, then a third, the last shot sending Glenn’s mouthpiece flying out of the ring. Nelson’s eyes turned glassy, his arms fell limp, and he started sinking softly to the canvas. Carter realized he could hear himself panting; the crowd was stunned into silence. Then pandemonium erupted. Spectators stood on their seats, whooping, gaping in disbelief at the knocked-out champion, cheering long and hard for Carter. The former hoodlum was now a hero. He had cocked a Sunday.

The triumph did more for Carter than prove he could slay a Goliath. It gave his life purpose and legitimacy. The boxing ring became his new universe, a place where his splenetic spirit and brawling soul were not only accepted but celebrated. His enemy couldn’t hide behind a warden’s desk or a police badge. He now stood face-to-face with his rival, and each bout had a moral clarity: the best man won, and if you fight Rubin Carter, you better bring ass to get ass.

After the Nelson Glenn fight, Carter never held an Army weapon again. Mullick cut through the Army’s red tape and transferred Carter to a Special Service detachment for boxers for the 502nd. They lived in their own building, three glorious floors for twenty-five men. The first floor held a vast recreational area, with ping-pong tables and pool tables, as well as a kitchen. The second floor was sectioned off with bathtubs and shower stalls, whirlpools and rubbing tables, while the top floor had secluded sleeping quarters. This was nirvana in the Army.

Carter was accepted immediately by the other boxers, including Glenn. For one who always preferred isolation, he felt strangely comfortable with these men. Some were black, some were Hispanic, some were white, but they were all fellow warriors. They felt no need to engage in the braggadocio common among the other soldiers. The only vocabulary that mattered was boxing. Past fights, future fights, championship fights. Carter spoke the same language as everyone else, and winners had the final say.

Soldiers who saw Carter’s matches have vivid memories of them more than forty years later. William Mielko, an Army sergeant, remembered Carter’s entering the ring in Munich to fight a member of the 503rd regiment. When the announcer declared the names of the boxers, two bugles blared, and a six-foot six-inch, 250-pound heavyweight entered the ring wearing a black hood over his head with two slits for his eyes. His body was wrapped in shackles. It was a frightening spectacle, but when the heavyweight rid himself of the hood and chains, he faced Carter. “Carter looked over at his trainer,” Mielko recalled, “and the trainer said, ‘First round.’ ” And that was the round in which Carter knocked him out with a furious combination of punches.

In one year Carter won fifty-one bouts—thirty-five by knockouts—and lost only five, and he won the European Light Welterweight Championship. But he was even more proud of a very different accomplishment.

Again, it was Hasson who tackled the matter of Carter’s speech impediment. No one had ever spoken to Carter about his stuttering except his parents, who said that the problem would disappear if he stopped lying. Rubin was at a loss. All he knew was that if anyone laughed at his clumsy tongue, he would flatten him. Hasson, however, saw Carter’s speech problem as a barrier not only to communication but to knowledge. Wrapped in a coat of silence, Carter came to believe what others said about him: he didn’t talk because he was dumb, and education was useless for someone with such low intelligence.

When they first met in the drop zone, Hasson’s comment—“I think you’ve got a problem”—was an oblique reference to Carter’s stammer. Later, on one of their walks across the base, Hasson spoke bluntly: “Your stuttering is a permanent troublemaker, and if you’re too embarrassed to go back to school, then I’ll go with you.”

The two men enrolled in a Dale Carnegie speech course at the Institute of Mannheim, where they were briefly stationed. The institute breathed prestige, with tall white marble columns and long, winding staircases. Carter thought it looked like something the Third Reich would have built. Many of the German students spoke more English than Carter did. The classes themselves were taught by kind, middle-age German men who imparted sage advice.

“Just think about what you’re going to say first, then say it,” one teacher said. Carter learned that he could sing songs without stammering, and he was able to replicate the relaxed fluidity of music in his own speech. He practiced by chanting Army cadences (“Hup-Ho-o-Ladeeoooo!”) as well as gospels from his church in Paterson. Words soon flew out of his mouth like doves released from a cage. Freedom! Powerful oratory was no stranger to Carter. He had five uncles and a grandfather who were all Baptist preachers, and his father’s voice was so resonant that churchgoers sat near him just to hear him pray. Rubin too proved to be a persuasive, even gifted, speaker who used ministerial cadences in stem-winding speeches. He also felt free to expand his own mind. His formal education had ended in eighth grade, and the only books he ever read were cowboy novels. Now he attended classes on Islam four nights a week and embraced Allah, renaming himself Saladin Abdullah Muhammad. “Allah is in us all, and man himself is God,” Hasson told Carter.

While Carter’s new religious faith would wane over the years, his discovery of books and passion for knowledge sustained him through his darkest hours. He never forgot what Hasson once told him: “Knowledge, especially knowledge of oneself, has in it the potential power to overcome all barriers. Wisdom is the godfather of it all.”

Discharged from the Army on May 29, 1956, Carter returned to Paterson with the intention of becoming a professional prizefighter. But he quickly discovered that he could not elude his past. He was arrested on July 23 for escaping from Jamesburg and sent to Annandale Reformatory, where inmates’ short-short pants evoked the image of incarcerated Little Bo Peeps. Carter was released from Annandale on May 29, 1957, but embittered about his reincarceration, he shelved his boxing ambitions, got a job at a plastics factory, and began drinking heavily. He liked to spend time at Hogan’s, a club that attracted pimps and hustlers, pool sharks, and virtually every would-be gangster in the black community. Carter was enthralled by the diamonds they wore, the bills they flashed, and the luster of their shoes.

Less than five weeks after he was released from Annandale, Carter left Hogan’s one day after a good deal of drinking. Walking through Paterson, he went on a brief, reckless crime spree. He ripped a purse from a woman, a block later struck a man with his fist, then robbed another man of his wallet. All the victims were black. When Carter reported to work the next day, the police arrested him. He pled guilty to the charges of robbery and assault but could never explain or excuse why he committed the crimes. He served time in both Rahway and Trenton state prisons, where he received various disciplinary citations for refusing to obey orders and fighting with other inmates. He did not make a particularly good impression on prison psychologists. In a report dated August 30, 1960, one psychologist, Henri Yaker, commented on Carter:

He continues to be an assaultive, aggressive, hostile, negativistic, hedonistic, sadistic, unproductive and useless member of society who will live from society by mugging and who thinks he is superior. He has grandiose paranoid delusions about himself. This individual is as dangerous to society now as the day he was incarcerated and he will not be in the streets long before he will be back in this or some other institution.

Carter was released from prison in September 1961, but that description—assaultive, sadistic, useless—would be used against him long into the future.

In the sixties, the center of the boxing universe was the old Madison Square Garden, with dingy, gray locker rooms and a balcony where rowdy fans threw whiskey bottles at the well – dressed patrons below. During bouts, a haze of smoke from unfiltered cigarettes hovered in the air. Men in sport shirts sipped from tin flasks in between rounds, while other fans sat with cigars, lit or unlit, that never left their lips. The Friday-night fights, televised across the country and sponsored by the Gillette Company, were an institution, and a marquee boxer could earn tens of thousands of dollars. But before reaching the big time, the pugs had to fight in satellite arenas in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Akron, and elsewhere. In later years, cable television would put any hot boxing prospect on the air after only a few fights. But at this time fighters typically had to learn their craft and pay their dues over several years before receiving that sort of publicity.

Rubin Carter felt he had paid his dues—in prison. While incarcerated, he concluded that prizefighting was his best hope of making a living and avoiding trouble. He trained in prison yards for four years, lifting weights, pounding the heavy bag, and accepting bouts with all comers. Once he left prison and entered the ring as a professional, it was soon evident that few could match his blend of intimidation, theatrics, and might. This crowd-pleasing style resulted in his first televised fight only thirteen months after he turned pro, when he knocked out Florentino Fernandez in the first round with a right cross to the chin. A black-and-white photograph of Fernandez falling out of the ring, his body bending like a willow over the middle rope as Carter glared down at him, sent an unmistakable message: the “Hurricane” had arrived.

Carter never really liked his boxing nickname. It was given to him by a New Jersey fight promoter, Jimmy Colotto, who saw the marketing potential of depicting a former con as an unbridled force of nature. Carter’s preferred symbol was a panther. In the ring, Carter’s trainers wore the image of a panther’s black head, its mouth open wide, on the back of their white cotton jackets. The image had nothing to do with race or politics (the Black Panther organization was not formed until 1966). Carter simply admired the panther’s speed and stealth, its predatory logic.

But Hurricane stuck, and for good reason. When Carter entered the ring, he was a force of nature. His head and face were already glistening from a layer of Vaseline. He wore a long black velvet robe and a black hood knotted with a belt of gold braid. There was something ominous, even alien, about him. When the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission ordered Carter to shave his goatee for a fight in Philadelphia, some sportswriters opined that the goatee was the seat of Carter’s power. The boxer looked foreshortened and brutally compact. The lustrous pate, the piercing eyes, the bristling beard, the sneering lips—and the violent criminal record—sent frissons of fear and delight through the crowd. Before a match, the announcer would introduce other boxing champions, past and present, in the crowd, and the conquerors would hop up in the ring, wave to the fans, and shake hands with the opposing fighters. Carter, however, refused to shake hands or even acknowledge their presence. Prowling around the canvas, he kept his eyes down and, in the words of one opponent, looked like “death walking.” When the battle began, he attacked straight on, punches whistling. No dancing, no weaving, no finesse. He rarely jabbed. Just heavy leather. Carter liked the violence.

While Carter often found trouble on the streets, his training camp in Chatham provided sanctuary. He and several sparring partners escaped to camp six weeks before a bout. They awoke at 5 A.M. and ran up to twenty miles through steep, wooded hills. Carter liked the dark frigid mornings best, when icicles formed in his goatee and the only sounds were the pounding of shoes on pavement and the stirrings of a sleepy cow.

After an eggs and bacon breakfast and rest time, Carter resumed his training in the small gym. He jumped rope for forty minutes, pumped out five hundred pushups, lifted neck weights, pounded the heavy bag and speed bag, pushed against a concrete wall to build muscle mass, and did chinups until he dropped.

A sparring session was no different from a televised fight: in each, Carter locked out the rest of the world and tried to destroy his opponent. At the beginning of his career, he lived in Trenton and trained in the same Philadelphia gym as Sonny Liston, the feared heavyweight who reigned as champion from 1962 to 1964. Liston’s heavy blows made it difficult for him to find sparring partners. One day Carter volunteered to go a few rounds, despite giving up five inches and fifty pounds. While most boxers spar to improve their footwork, punching combinations, or defensive maneuvers, neither Liston nor Carter had the patience for such artistic subtleties. Both were former convicts—Liston for armed robbery—and they rarely exchanged more than a few words. Theirs was an unspoken code of respect through pugilistic mayhem, and they sparred fiercely and repeatedly. But after one three-round session, Carter removed his battered headgear and found it soaked with blood. He was bleeding from both ears. He fled from Trenton that night and moved to Newark. He knew if he returned to the Philadelphia gym the next day and Liston needed a partner, he would do it again. He could never turn down a challenge, even if it meant risking serious injury.

Like Liston, Carter beat his sparring partners unmercifully. To soften the blows, Carter used oversize gloves and his partners wore a foam rubber protective strap around their ribs. In training camp, he sparred against three or four boxers a day, always punching against a fresh body. These sessions were followed by more calisthenics, then by a few rounds of shadowboxing, then by a shower and a rubdown. After a dinner of steak, fish, or chicken, Carter took a walk in the clean country air and thought about the next day’s workout.

Only two years after he became a professional fighter, Carter wanted a shot at the middleweight title. He had won eighteen and lost three, with thirteen knockouts. But in October 1963, he lost a close ten-round decision to Joey Archer, and he needed a victory to put him back on track for a shot at the championship. That put him on a collision course with Emile Griffith.

Griffith was a native of the Virgin Islands who moved to New York when he was nineteen. His boss encouraged him to try his hand at boxing, and he was an instant success, winning the New York Golden Gloves. He turned professional at twenty. Griffith liked to crouch in the ring, stick his head in the other guy’s chest, and pound the midsection. He could also dance and jab, backpedal and attack; he never tired. And he was deadly. In a bout at Madison Square Garden on March 24, 1962, Griffith took on Benny “Kid” Paret for the third time in less than twelve months, the decisive match in a bitter war between the two men. Paret provoked Griffith at their weigh-in by calling him maricon, “faggot.” That night, Griffith was knocked down early, but he pinned Paret in the corner in the twelfth round and felled him with a torrent of angry punches, prompting Norman Mailer to write later: “He went down more slowly than any fighter had ever gone down, he went down like a large ship which turns on end and slides second by second into its grave. As he went down, the sound of Griffith’s punches echoed in the mind like a heavy ax in the distance chopping into a wet log.”

Paret was removed from the ring on a stretcher, lapsed into a coma, and died ten days later; he was twenty-five.

At the end of 1963, Griffith was the champion of the welterweight division (for boxers 147 pounds and under) and had been named Ring magazine’s Fighter of the Year with a record of thirty-eight wins and four losses. Now he wanted a shot at the middleweight crown (for boxers 160 pounds and under), and that led to his match with Carter.

Their bout was to take place in Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena on December 20. The two men were sparring partners and friends, but in the days leading up to the match, Carter launched a clever campaign to strike Griffith at his point of vulnerability: his pride. The idea was to provoke him before the fight so that he would abandon his strongest assets—his speed and stamina—and go for a quick knockout. Carter began planting newspaper stories that Griffith was going to run and hide in the ring and hope that Carter tired. In a joint television interview the day before the fight, the host asked Griffith if he dared to stand toe-to-toe with the Hurricane.

“I’m the welterweight champion of the world,” Griffith snapped. “I’ve never run from anyone before, and I’m not about to start with Mr. Hurricane Carter now!”

“Then I’m going to beat your brains in,” Carter shot back.

Griffith laughed in the face of Carter’s hard glare. “I’ve never been knocked out either,” Griffith said. “But if you don’t stop running off at the mouth, Mister Bad Rubin Hurricane Carter, I’m going to turn you into a gentle breeze and then knock you out besides.” Griffith was now seething, so Carter raised the temperature a little more.

“Knock me out!” Carter said, turning to the live audience. “If you even show up at the arena tomorrow night, that’ll be enough to knock me out! I oughta cloud up and rain all over you right here. You talk like a champ, but you fight like a woman who deep down wants to be raped!”

The audience, knowing what happened to Benny Paret, gasped. Griffith clenched his jaw. Carter had laid his trap.

The following night, the city’s steel plants and foundries spewed smoke into the frozen air. Inside the Civic Arena, Griffith’s mother was in the crowd, and the champion entered the ring as a confident 11–5 favorite. Griffith started out methodically, firing jabs, standing toe-to-toe, swapping punch for punch. He wanted to prove that he could take Carter’s best shots and win a slugfest. This was exactly what Carter had hoped for.

Carter popped him in the mouth with a stiff jab; Griffith responded with an equal jolt to Carter’s mouth. Carter pumped a jab to his forehead; Griffith fired one back on him. Carter backed up, looked at him, snorted, then raced in with a jab followed by a powerful left hook to the gut.

The air came out of Griffith, who tried to grab Carter, but Carter slipped away. “Naw-naw, sucker,” Carter mumbled through his mouthpiece. He drilled home another salvo of lefts and rights—“You gotta pay the Hurricane!” Carter yelled—then dropped Griffith with a left hook.

“One! … Two! … Three.”

The crowd was stunned into silence, then stood and cheered. Griffith staggered to his feet to beat the count, but he was now an easy target. Carter smashed left hooks to the body and devastating rights to the head. Griffith dropped to the canvas, badly hurt. He tried to stand but stumbled instead. The referee, Buck McTiernan, stepped in and stopped the fight. The time was two minutes and thirteen seconds into the first round. “A left hook sent Griffith on his way to dreamland!” the television announcer yelled.

Carter’s upset cemented his reputation as one of the most feared men in boxing. It also earned Carter a shot at the title the following year. But the Griffith fight marked the pinnacle of his boxing career. Carter lost his championship bout on December 16, 1964, to Joey Giardello, a rugged veteran whose first professional fight had been in 1948, in a controversial fifteen-round decision. Giardello’s face was puffed into a mask while Carter was unmarked, and a number of sportswriters who saw the fight thought Carter won. But challengers typically have to beat a champ decisively to win a decision, and Carter didn’t.

The bout occurred on December 16, 1964. The following year, Carter received another jolt—this time, political. He was invited to fight in Johannesburg, South Africa, a country about which he knew virtually nothing. He had never heard of Nelson Mandela or the African National Congress or even apartheid. But just as the Army exposed him to bigotry in the Deep South, boxing now put him in the midst of a more virulent racism. Arriving in Johannesburg a couple of weeks before his September 18 bout, he was guided around the city by Stephen Biko. In years to come, Biko would become the leader of the Black Consciousness movement, advocating black pride and empowerment, and would found the South African Students Organization. But in 1965, he was an eighteen-year-old student and fledgling political activist, and he gave Carter a quick education in black oppression. Walking through Johannesburg, the American’s roving eye glimpsed a tight-skirted white woman. “Whoa, man!” he said. Biko grabbed Carter’s arm. “You can’t say that. They’ll kill us! They’ll kill us!”

Racial strife was indeed high. The previous year, Nelson Mandela and other black leaders were handed life sentences for conspiring to overthrow the government. The ANC had been banned in 1961; but clandestine meetings were still being held, and Biko took Carter to some of these nocturnal gatherings. There he learned about black South Africans’ bloody struggle, dating almost two hundred years, for political independence. He also had his own encounter with the South African police. He was almost arrested one night for walking outside without a street pass.

The boxing match was against a cocky black fighter named Joe “Ax Killer” Ngidi who had a potent right hand. More than 30,000 fans packed into Wemberley Stadium on a sunny afternoon, and as Ngidi danced about the ring in a pre-bout warm up, Carter noticed that some of the fans were carrying spears.

“I don’t know what that means,” his advisor Elwood Tuck told him, “but get that sucker out of there quick.”

Carter was confident. South African boxers, he believed, viewed the sport as dignified and noble but lacked savagery. That shortcoming could not be applied to Carter, and even though he was a foreigner, his ferocity made him a crowd favorite in South Africa. When he KO’d “Ax Killer” Ngidi in the second round, fans stood on their feet, raised their spears and yelled, “KAH-ter! KAH-ter!” But after Carter reached his dressing room, he was pinned in by a mob of supporters, and the scene turned ugly. To leave the stadium, a battalion of gun-carrying Afrikaner cops formed a wedge and told Carter and his entourage to follow its lead. As they pushed through the crowd, a white officer pummeled several black fans. Carter, outraged, moved to strike the cop, but was blocked by one of his handlers and was once again reminded that such a move would ensure his own demise.

In the following days, Carter was named a Zulu chief outside Soweto and given the name “Nigi”—the man with the beautiful beard. He was now an African warrior, and he wanted to apply the same principles in his second homeland that he always applied in the U.S.: blacks must use whatever means necessary, including violence, to defend themselves. From what he could tell, South African blacks were defenseless, armed with rocks and spears against the Afrikaners’ guns and rifles. Before Carter left Johannesburg, he pledged to Stephen Biko that he would return.

Carter had committed crimes before, but now he was going to do something far more dangerous. He was going to smuggle guns to the ANC. First, he prowled bars in New Jersey and New York, where hardluck customers traded their guns for drinks and tavern owners ran a second business in arms sales. Carter accumulated four duffel bags for their weapons, then persuaded Johannesburg promoters to set up another fight. This time, his opponent would be an American, Ernie Burford, against whom Carter had split two previous matches. That Carter would travel all the way to South Africa to fight another American made no sense to outsiders, and he told few people about his true motivation, not even Burford. If the South African authorities caught him running guns to the ANC, he would probably never have left the country alive. But the trip turned out to be a great success. He delivered the guns to a grateful Biko, and he knocked out Burford in the eighth round on February 27, 1966.

Eight months later, Carter was arrested for the Lafayette bar murders, and he never heard from Stephen Biko again.

In a few short years, Biko founded the Black Consciousness movement, advocating black pride and empowerment, and he would become one of the most celebrated leaders of black South Africans’ fight against a murderous regime. His activism, however, frequently placed him under police detention, and in 1977 he died from head injuries while under custody, provoking international outrage. He was thirty years old.*

After Carter’s loss to Giardello, his boxing career lasted for twenty-two more months. During that period he won 7, lost 7, and had 1 draw. (He ended his career with 28 wins, 11 losses, and 1 draw.) He blamed the losses on increased police and FBI harassment, in New Jersey and elsewhere, and there is credibility to that excuse. The Saturday Evening Post article, which included Carter’s intemperate remarks about the police and his own ruffian past, was published in October 1964. Carter, according to Paterson police records, was arrested twice in the next six months on “disorderly person” charges. (He was found not guilty on one charge and paid a $25 fine on another.) In a sport that requires complete focus, Carter’s concentration was no doubt disturbed by these rising tensions with the law.

But Carter’s own stubbornness hurt him. He worked out with intensity but resisted his trainers. One, Tommy Parks, devised an ingenious double-cross. He began giving Carter “opposite commands.” If he wanted Carter to do roadwork the next morning, he would instruct his fighter to sleep late. Five A.M. would roll around and, sure enough, Carter was ready for roadwork. His footwork needed sharpening? Parks told him to concentrate on his punching. Invariably, Carter followed the “opposite command,” thereby doing exactly what Parks desired.

Carter also lacked discipline. During training, he would get bored at night, sneak out of camp, and go to Trenton or another town to meet women and carouse. He never drank in front of his trainers, but Parks thought he knew when Carter had been tipping the bottle. His skin seemed to grow yellow and his eyes were in soft focus. Carter once had a sparring match in Newark with a tough but unaccomplished fighter named Joe Louis Adair. Carter had been drinking the previous night, and he was sluggish in the ring. Adair knocked him down in the first round, and a newspaper published a story about the Hurricane’s improbable pummeling. “Rubin was a Mike Tyson with heart,” Parks said in an interview years later. “But drinking was the bane of his career.” Carter, asked about that assessment, agreed.

Parks specialized in working with troubled kids, but he was removed as Carter’s trainer in 1963 because the boxer’s manager wanted a white trainer to improve Carter’s marketability on television. But the change hurt in the ring. Carter preferred black trainers like Parks and said his subsequent white trainers varied in effectiveness. His own effectiveness may also have been diminished because he stopped scaring opponents. His invincible armor, once cracked, gave his competitors more confidence. Carter’s image and tenacity still made him a crowd favorite, though, and at the end of 1965 he was ranked fifth among middleweights by Ring