Читать книгу The Nature of College - James J. Farrell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

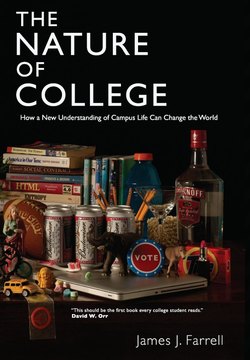

2) Consumption, Materials, and Materialism

ОглавлениеTo parents and professors, students are people engaged in academic learning. To America’s commercial interests, however, students are materialistic consumers and a major market niche. In fact, whole books have been written on taking advantage of this segment of the population. David A. Morrison’s Marketing to the Campus Crowd, for example, notes that college students offer corporate America opportunities for “branding, selling, sub-segmenting, and new product strategies,” and that, conveniently, college students can be less price-sensitive than other consumers, especially when subsidized by what Morrison calls the “Bank of Mom and Dad.” College students are a profitable market, says Morrison, because of the sheer volume of their discretionary spending, along with their high concentration, rapid turnover, avid willingness to experiment, propensity for innovation and early adoption of technology, ever-changing brand loyalties, strong influence on other key consumer segments (and the mainstream marketplace as a whole), and receptivity to the right advertising, sampling, and promotions (in contrast to the average consumer). “The basic mantra behind college marketing,” Morrison claims, “is to generate short-term financial gains to the bottom line and simultaneously establish long-term brand loyalties.” And, as marketing consultant Peter Zollo says of younger students, “School delivers more teens per square foot than anyplace else!”1

If we only consumed discrete objects disconnected from the rest of the world, this might not be a problem, but in buying stuff, we buy into a system of stuff called materialism. Materialism is the way that Americans manage resource flows, both intentionally and unintentionally. When a student buys a computer, she thinks about its advantages for her connectedness, including (sometimes) her connection to academic resources. But while she’s thinking about Internet access and word processing, she’s actually world processing: setting off a chain of demand and supply that has far-reaching environmental consequences. She can ignore the environmental impacts of the purchase because the common sense of consumption lets her focus on her material desires instead of the material consequences of her decisions.

Locating college culture within consumer culture, then, helps us to see how American culture routinely expects us to consume stuff that consumes the world. It helps us to see how advertising pressures and peer pressures combine to make our consumption both “normal” and normative, despite its extensive environmental impacts. At the same time, however, our understanding of our consumption helps us to take control of it, so that we can change the culture of consumption to increase both our happiness and our harmonies with the natural world.