Читать книгу The Ragged Road to Abolition - James J. Gigantino II - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

Abolishing Slavery in the New Nation

Julian Niemcewicz, the exiled Polish statesman and writer, moved to Elizabethtown in 1797 and married Susan Livingston Kean, the niece of former governor William Livingston. He bought an eighteen-acre farm and settled into his new life as a gentleman farmer. His wife had a close association with slavery, as her deceased husband, John Kean of South Carolina, owned over one hundred slaves. After Kean’s death in 1795, Susan owned and traded those slaves, continuing to do so after her remarriage. Even though slavery was integral to the couple’s household, Niemcewicz remained puzzled as to slavery’s place in American society. After discovering that Elizabethtown’s prison kept only “negro slaves who have deserted their masters,” he wondered how Americans could support slavery in a “free and democratic Republic,” especially after they had just fought a long and bloody revolution for that freedom.1

Niemcewicz recognized what historian Edmund Morgan eventually termed “the American Paradox,” the growing interest in slavery in the aftermath of a revolution for freedom. While the American Revolution represented a new birth of political freedom, most slaves remained in bondage after the guns fell silent. Economic imperatives allowed for slavery’s growth in the Deep South while revolutionary ideology pressed for the institution’s end in the Upper South and the North. This freedom paradox helped convince Massachusetts, Vermont, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island to either abolish slavery or pass gradual abolition laws in the 1780s. Likewise, Virginians, Marylanders, and Delawareans questioned the institution by forming abolition societies and loosening manumission restrictions. Though no Chesapeake states went as far as abolition, economic changes and rhetoric equating British tyranny to slavery’s oppression slowly altered perceptions of the institution.2

However, New Jersey did not immediately follow the lead of Pennsylvania and New England. As opposed to Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, who believed the American Revolution was abolition’s “seed,” I maintain that the Revolution helped entrench slavery deeper in New Jersey and served as a bulwark against freedom. The years after the war likewise marked an increase in slavery’s numerical pervasiveness and overall popularity. It took twenty years of abolitionist activity, protests from slaves, and a political realignment to force New Jersey to adopt gradual abolition in 1804.3

In this period of struggle, white and black New Jerseyans debated the ideas of freedom within the context of a growing economic and social interest in slavery. While slavery grew, Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS) members and Jersey Quakers founded the state’s first abolitionist organization, the New Jersey Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, in 1793. However, this largely West Jersey Quaker organization remained weak throughout its existence and actually aggravated racial tensions. By 1800, East and West Jersey had fractured on the slavery question. West Jersey had largely eliminated slavery, while in contrast, most East Jersey whites supported bound labor and saw the West’s advocacy of abolition as an intrusion into their economic livelihood. Slavery became the divisive issue that inflamed a long history of disunity between the two regions that in turn delayed abolition.

Neither abolitionist rhetoric nor resistance from slaves alone tipped the state toward gradual abolition. Instead, the partisan debates between Federalists and Democratic Republicans in the 1790s dealt slavery’s final blow. Unlike the movements in other states where abolitionism developed organically without strong political affiliations, Jersey Democratic Republicans advanced abolitionism to showcase their political suitability as adherents to the true spirit of 1776. They used abolition as a symbol of that revolutionary spirit, which united East and West Jersey interests and empowered the new party politically and morally.4

Gradual abolition was a consequence of this political wrangling and, as in other states, most white New Jerseyans supported it for self-serving reasons. Most abolitionists “dress[ed] it up as a gift” given from “the empowered possessors of freedom to the unfree and disempowered slave.” Such motivations, though, should not mitigate the actions of slaves who advocated for their own freedom in the 1790s. Indeed, many achieved freedom or an amelioration of their condition in slavery and I explore their experiences as well, especially since they helped create the conditions that allowed legislative abolition occur. In the end though, New Jersey offered fewer avenues for slaves to negotiate than other northern states due to slavery’s growth in the state. The lack of strong white support for abolition independent of politics allowed slaveholders eventually to exploit loopholes in the law, which forced most Jersey slaves to walk a complicated path toward freedom even after gradual abolition began in 1804.5

* * *

In 1784, Connecticut and Rhode Island followed Pennsylvania and passed gradual abolition laws while New Jersey abolitionists, supported by Governor Livingston, proposed that their state follow suit. Livingston strongly supported abolition, writing in 1786 that slavery was “an indelible blot . . . upon the character of those who have so strongly asserted the unalienable rights of mankind.”6 In 1785, Livingston and Quaker activist David Cooper had urged the legislature to ban slave importations and enact gradual abolition. Cooper himself readily believed that blacks and whites “are born equally free” and claimed that because the United States had just fought a war for freedom, Americans could not withhold that freedom from blacks. This revolutionary rhetoric fused religious ideology, morality, and Enlightenment ideals into the postwar abolition fight. Hunterdon County abolitionists, for instance, called for a restoration of the “reverence for liberty which is the vital principle of a republic.”7

The 1785 abolition proposal failed because legislators still believed that stripping slaveholders of their property would push the state deeper into economic recession while continuing slavery could spur recovery. Even Pennsylvania, which enacted gradual abolition in 1780, grappled with abolition’s economic consequences in the midst of war. Abolitionist William Rawle, remembering the 1780 decision years later, claimed that “a fear of inconveniences on account of the war then raging probably prevented the legislature from going further” to pass a stronger abolition law.8 New Jersey, a battlefield for the entire war, registered significant economic losses, especially in the heavily slave-populated areas bordering New York. Whites there opposed a quick move toward abolition; Quaker-dominatedWest Jersey supported its speedy adoption. This sectional split furnished “some of the northern counties” who saw “too rapid a progress in the business . . . with an excuse to oppose it altogether.” Livingston had hoped that abolition would “have gone farther,” but economic distress and slaveholder’s defense of property rights limited political opportunities to abolish slavery.9

Livingston also identified the state’s decision to sell the remaining confiscated loyalist slaves at auction at the end of the war as the “fatal error” that doomed abolition in 1785. Their sale gave “a greater sanction to legitimate the abominable practice” and questioned the justice of mandating “the manumission of slaves, without compensation to the owners” while the state simultaneously “avail[ed] itself of the proceeds in cash of the sales of similar slaves.” Livingston concluded that “it must be wrong in both cases or in neither of them.” The decision to sell loyalist slaves therefore opened lawmakers to charges of hypocrisy if they forced abolition after profiting from the state’s own slaves, resulting in few working to advance black freedom.10

After abolition’s 1785 failure, slavery grew increasingly pervasive in both New Jersey and New York. In the 1790s alone, the slave population of New York City expanded by 22 percent and the number of slaveholders by a third. Few slaves were freed by manumission.11 In New Jersey, the number of slaves increased by 9 percent though, as most of West Jersey was dismantling the institution, that figure clouds its growth in the East. In the 1790s, the slave population increased in seven of the state’s thirteen counties. Essex had the highest growth rate (30 percent), while Bergen and Morris each saw a 22 percent increase. This growth of the slave population reflected the need to rebuild the devastated East Jersey economy, the growing demand for New Jersey’s grain crops, and the dearth of available laborers. As young men migrated to larger cities after the war, immigration from Europe no longer filled the demand. In 1797, Niemcewicz complained that “hired hands are expensive and hard to get,” while the owner of a Paterson textile mill reported “three-quarters of [the] machines lay idle because of lack of hands.” Slave labor filled this gap in East Jersey especially as farmers hoped to profit from the increased value of wheat and flour that the nation had seen between 1780 and 1790. Prices had nearly doubled in that decade and increased throughout the 1790s as Europe descended into war. In comparison, West Jersey had “but few slaves and the number of these continually diminishing” according to the New Jersey Abolition Society in 1801, since by that year, three-quarters of the state’s 12,500 slaves lived in East Jersey’s five counties.12

Table 1. Slave Population Growth and Decline by County, 1790–1800

Far from a small cadre of older New Jerseyans who stubbornly kept their slaves against an increasing abolitionist spirit, New Jersey’s slave system attracted new whites interested in slavery’s benefits. Yearly tax records from Newark (in East Jersey) and Morris (in West Jersey) between 1783 and the early nineteenth century suggest little numerical change in the number of slaves held but reveal the popularity of slaveholding among whites. In Newark in 1783 and 1789, 88 different whites owned the city’s approximately 60 slaves. Only 31 percent of Newark’s 1783 slaveholders still owned slaves in 1789, yet few moved out of Newark. Of the 52 slaveholders on the 1789 list, 30 still appeared in 1796, but only 8 continued to hold slaves. Whites who had previously not owned slaves purchased them after the war even as other northern states had begun to abandon bound labor.13

Few slaveholders in Newark and Morris manumitted their chattel, further illustrating a continued interest in slavery. Between 1783 and 1804, Newark slaveholders provided freedom in 10 of 59 wills and probates. For example, Augustine Bayles of Morris County wanted slavery to continue in his family after his death. Bayles bought Quamini in 1780 and promised him freedom at his death if Quamini served him faithfully. On his deathbed in 1785, Bayles told Quamini that he had indeed “been a good and faithful boy,” but one of Bayles’s friends, Daniel Layten, argued that Bayles needed to provide for his wife after his death. Bayles rescinded his manumission offer and ordered Quamini to serve his wife until she remarried, at which time he would be freed. Bayles’s widow, who eventually remarried, held Quamini in violation of Bayles’s wishes. Although Quamini successfully sued for his freedom with the help of local abolitionists, most slaves in New Jersey never received such freedom after their owner’s death.14

As expected, sales of Jersey slaves increased after the Revolution with Jersey slaveholders advertising 201 slaves for sale in newspapers from 1784 to 1804, forty of them children attached to their parents. Female slaves appeared most frequently (60 percent), as enslaved domestic servants became status symbols who could also reproduce if the state ever enacted gradual abolition. However, slaves used in agricultural or industrial production remained valuable commodities and represented a large proportion of these sales.15 The use of slaves in nonagricultural occupations also became popular as slaveholders adapted bound labor to the new industrializing economy. For instance, the Andover Iron Works in Amwell and the Union Iron Works in Hunterdon County both used slave labor. Andover, for example, employed a slave, Negro Harry, in the late 1790s as a hammer-man and allowed him to hire himself out to other forges when business slowed. Likewise, salt works in East Jersey also hired slave labor; one such business purchased Sampson in 1790 to cut wood and do other odd jobs.16

As the number of slaves increased, racism reinforced slavery’s presence as an intense discussion of black distinctiveness and negative characteristics began in local print culture. Reprints of Edward Long’s History of Jamaica (1774) showed Mid-Atlantic whites that blacks were a separate race and sensationalized their association with savagery and war. Almanacs picked up on these discussions and continually portrayed Africans as heathens or devilish apes. Depictions of blacks in literature as inferior and associated with evil followed. For instance, the author of a 1797 pamphlet titled The Devil or the New Jersey Dance described six young whites who hired a black fiddler for an evening. Instead of a single night of festivities, he kept the group for more than thirty days, leaving them “dancing on the stumps of their legs . . . their feet being worn off and the floor streaming with blood.”17

Some New Jerseyans, like Dutch Reformed minster John Nelson Abeel, complained of the dangers of blacks and whites living in close proximity on equal footing and suggested how blacks’ presence could destabilize the social order. Abeel offered that “those negroes who are as black as the devil and have noses as flat as baboons with great thick lips and wool on their heads,” along with “the Indians who they say eat human flesh and burn men alive and the Hotentots who love stinking flesh,” could prove dangerous if freed.18 A 1792 newspaper reiterated this sentiment by claiming that blacks bore “the marks of stupidity . . . in the countenances composed of dull heavy eyes, flat noses, and blubber lips.”19 In New York, racist rhetoric derailed that state’s abolition efforts in the 1780s, while in New Jersey it similarly worked to show blacks as unworthy of freedom.20

Slaveholders who embraced the institution in the 1790s convinced legislators that the institution needed continued regulation and in 1798 they passed a revised slave code that reaffirmed slavery’s legality and confirmed the inclusion of any “Indian, Mulatto or Mestee” currently held as a slave in that category. The reaffirmation of Indian slavery resulted from a court case one year earlier in which Rose, “a North Carolina squaw,” argued that her Indian status “furnishes at least prima facie evidence of her being free.” Elisha Boudinot, a future Supreme Court Justice and abolitionist who assisted Rose, argued that Indian slavery had no basis in law or practice. The defense pointed to slave laws passed in 1713, 1768, and 1769 that made “no discrimination . . . between negroes and Indians.” The court agreed and claimed Indian slaves “stand precisely upon the same footing . . . to be governed by the same rules as that of Africans.” The 1797 court decision and the 1798 statutory reaffirmation of Indian slavery strengthened the differentiation between free whites and enslaved nonwhites and reinforced the place of bound labor in New Jersey.21

The 1798 law also regulated slave behavior, levying restrictions to strengthen the institution. It banned slaves from assembling in a “disorderly or tumultuous manner,” prohibited their movement after 10 p.m., and affirmed longstanding prohibitions on slaves’ ability to testify against free persons. The legislature continued to strengthen slavery in 1801 when it revised a law on slave punishment. That law, like those in the South, allowed courts to sentence slaves convicted of arson, burglary, rape, highway robbery, attempted violent assault and battery, or attempted assault and battery with intent to commit murder to sale outside of New Jersey. Sale or transfer to the Deep South, discussed extensively in Chapter 6, further demonstrated the Revolution’s failure to advance abolitionism.22

* * *

As slavery grew in East Jersey, Quakers and slaves worked to dismantle it in West Jersey. The Society of Friends had been advocates for abolition early on and therefore took the lead in advancing statewide abolition. By 1800, 80 percent of Burlington County blacks and 91 percent of Gloucester’s lived free. In comparison, only 11 percent of Essex County blacks and 6 percent of Bergen’s had gained freedom. This Quaker antislavery activity further bifurcated New Jersey, leaving West Jersey to develop into a free society even before the passage of a gradual abolition law while the institution remained entrenched in the East.23

However, even as Friends advanced abolition, few accepted free blacks as members of their meetings with equal status. Race still proved a barrier for Quakers, though they allowed black participation in certain religious activities. For example, John Woolman officiated the marriage of William Boen, a former Mount Holly slave, even as, the “way not opening in Friends’ minds, he was not received” by the meeting as a member. Instead, he remained affiliated with them until 1814, when the meeting finally granted him full membership.24

Like Boen, other Jersey blacks attended Quaker meetings in Burlington, Gloucester, and Salem in what became a way for Friends to collectively repay a debt owed for their participation in slavery. This Quaker “guilt,” usually manifested as paternalistic assistance, helped the Society become the largest (and only) lobbying group for black freedom in the state. The Salem Monthly Meeting felt so passionately about these meetings that they rearranged their regular worship schedule to allow blacks to use their meeting house at more convenient times. These meetings provided West Jersey blacks with an organized structure to create networks of both white and black allies, which they used to develop business ties, free family members, and gain educational opportunities. In sum, many ex-slaves saw these meetings as an opportunity to develop the bonds needed to survive in a state still ensnared in slavery.25

Calls for abolition routinely came directly from Quaker meetings as well as from those activists who had worked with Governor Livingston. In 1786, for instance, the Philadelphia Meeting for Sufferings, which included New Jersey, wrote to the state legislature to “restore this injured people to their natural right to freedom” and quickly enact gradual abolition. In 1788 they again called for abolition and stronger restrictions on the slave trade. Likewise, in 1792, the Meeting of Sufferings sent a delegation to Trenton to discuss ways to enact gradual abolition. That same year, Jersey Quakers joined those from Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland to petition for the immediate abolition of slavery, citing the “oppressed condition of the African race” and their position as “solicitors on their behalf” following the “precept and injunction of Christ” to mitigate slaves’ pain and suffering.26 New Jersey Quakers again spoke in 1799 through the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to the nation at large for the “spirit of meekness and wisdom in promoting” abolition.27

Quakers, especially abolitionist James Pemberton, also allied with Governor Livingston and worked to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. They sponsored a law that prohibited both the importation of slaves from Africa and of slaves from other states who entered the country after 1776, which tied the measure directly to the Revolution. However, as opposed to New Englanders who organized against the widely unpopular and sinful slave trade at the expense of local slaves, Livingston and his coalition fused the abolition of the slave trade with abolition at home. Despite the renewed push for gradual abolition in New Jersey, Livingston eventually abandoned the combined plan, believing that trying for both ran “the risk of obtaining nothing,” especially since gradual abolition had failed the previous year. Therefore, he claimed it was “then prudence not to insist upon it but to get what we can and which obtained paves the way for procuring the rest.”28

The attack on the slave trade tied Jersey Quakers to a much larger national coalition against the “barbarous custom” of slave trading. By the 1760s, both northerners and southerners, including New Jerseyans, had limited access to the slave trade by levying prohibitive duties. Although the Crown repudiated most of these duties, the Second Continental Congress enacted a ban on slave trading that lasted until 1783. Afterward, activists in individual states who opposed the trade worked to ban it and by 1790, as one newspaper article claimed, “the citizens of the United States [were] so generally united” in the belief of the trade’s barbarity that it made it an easy abolitionist target.29 Even though Georgia imported slaves until 1798 and South Carolina reopened the slave trade in 1803, most Americans opposed it. Closing the slave trade simultaneously helped fulfill the idea of revolutionary freedom, increased the value of those currently enslaved, and, as many thought, limited the potential for future slave rebellions. In New Jersey, Livingston’s coalition found common ground with slaveholders and banned the slave trade in 1786. However, the victory did little to weaken slavery’s hold in New Jersey because few slaves had been imported since the 1760s.30

Although unable to abolish slavery in New Jersey, Quakers and their allies petitioned the legislature relentlessly to make voluntary manumission of slaves easier, arguing that the colonial law requiring slaveholders to post manumission bonds dissuaded owners otherwise inclined to free their chattel. The same 1786 law that banned the slave trade allowed masters to manumit slaves age twenty-one to thirty-five without bond after an examination by two overseers of the poor and two justices of the peace who would certify the slave would not become destitute. It also required owners to support former slaves if they ever required poor relief. Following this law, Robert Armstrong of New Brunswick brought his slave Tony for examination before two overseers and two justices of the peace in 1790. However, when Tony fell into poverty six years later, Armstrong claimed he had released any and all claims on Tony “to all intents and purposes as if he has never been my slave,” to escape paying for his care. Of course, the law prevented this very action and Armstrong had to support his indigent former slave.31

The continued efforts of abolitionists in the 1790s to expand the availability of manumission helped many slaves negotiate freedom for themselves. In 1792, for instance, Burlington and Hunterdon County abolitionists petitioned the legislature to expand the manumission criteria by permitting masters to manumit slaves under twenty-one if the ex-slave was then indentured until twenty-eight. This proposal mimicked Pennsylvania’s gradual abolition law and encouraged slaveholders to sign away their future rights to children after a period of service. Although nothing came of the petition, it shows their desire to emulate a graduated system of abolition, one that extracted labor in exchange for freedom. This became the blueprint for the abolition plan enacted in 1804. In a larger sense though, the expansion of manumission was critical to hundreds of West Jersey blacks who used this viable legal avenue of freedom to achieve what they had strived for since the Revolution.32

The 1786 law also levied fines against masters who abused their slaves, further supporting Quaker amelioration efforts. This requirement led Henry Wansey, an English traveler who toured New Jersey in 1794, to observe that “many regulations have been made to moderate [slavery’s] severity.”33 The law responded to a number of abuse cases, including one involving Monmouth County slaveholder Arthur Barcalow, who whipped his slave Betty for failing to follow his direction to return home. Despite acceding to her master’s will, Barcalow continued to beat Betty. A neighbor testified that Betty “was dead . . . [her] arm bloody and appeared to have been cut with a whip.” The coroner concluded that Betty died of blunt force trauma caused by the broom stick Barcalow wielded, which led a local jury to convict Barcalow of murder. Abolitionists made sure that all mistreatment, not just Barcalow’s extreme example, would be punished under the law. This section of the 1786 law, while spearheaded by abolitionists, helped slaveholders defend slavery as they claimed that their slaves lived as a protected class of servants. Slavery therefore acted as a positive benevolent institution, worthy of support.34

A regulation that mandated masters teach their young slaves to read, also part of the 1786 law, further bolstered a paternalistic defense of slavery and reflected the abolitionist desire to educate young slaves with skills to prepare them for possible future freedom. No record of any slaveholder being fined under this law remains but evidence suggests that some slaveholders, like Aaron Malick, did send their slaves to school, which likely helped some achieve freedom in the future. However, slaveholders before the 1820s viewed reading “as a tool that was entirely compatible with the institution of slavery.” Writing, in contrast, represented an “intrinsically dangerous” skill that slaveholders worked diligently to limit. As abolitionists never forced the issue of writing, the promotion of slave reading seemingly fits into the larger campaign to quell Quaker guilt.35

Quaker efforts to ease manumission requirements and temper slave treatment accentuated the differences between East and West Jersey. Slavery in West Jersey, due to Quaker influence, declined quickly due to manumissions. In Burlington County, for example, the county clerk recorded seventy-five manumissions between 1786 and 1800, which helped shrink the county’s slave population by 17 percent. Similarly, between 1790 and 1800, Gloucester’s slave population declined by 68 percent and Cumberland’s by 38, while those in East Jersey grew by 20 to 30 percent. These ex-slaves added to the already burgeoning free black community that had formed as a result of earlier Quaker manumission efforts.36

Both Quaker advocacy of abolition on a personal level and individual slaves negotiating with masters to gain their freedom worked simultaneously to destabilize the institution. For instance, John Hunt, a member of Burlington County’s Evesham Meeting, recorded his extensive efforts to convince recalcitrant Quaker slaveholders to abandon slavery. These Quakers put pressure on slaveholders to manumit at the same time slaves themselves pressured them for freedom from within. In July 1787, Hunt visited the home of Joseph and Mary Garwood, fellow Evesham Friends, to discuss manumission plans. Joseph purposely avoided meeting with Hunt, which led Hunt to instead “press things closest home upon” Mary. Ten days later, Hunt revisited the Garwoods with fellow Quakers Samuel Allinson and Elizabeth Collins. Mary again stopped the trio from seeing her husband, claiming he was “indisposed with bad fits.” Hunt suspected that Garwood had feigned illness to avoid a confrontation. In this case, Garwood’s slaves and their white allies failed in their negotiations for freedom as Garwood sold them to stave off potential economic losses.37

On the other hand, Hunt and Allinson convinced John Cox to manumit his slaves in 1787, though they failed to accomplish the same with Jacob Brown the following year. Likewise, Hunt visited the home of Micajah Wills and his wife several times between 1787 and 1794, but ultimately failed to convince Wills to manumit his chattel, though he kept in close contact with Wills’ slaves. In 1794 Hunt attended a funeral for one of them, where he remarked that while the slaves “behaved very sober,” the whites in attendance failed to keep quiet throughout the service, a jab at the demeanor of those who refused abolition.38 Other Quakers, including Allinson’s son William, continually toured New Jersey trying to convince individuals to free their slaves. In 1804, for instance, William “set out on a tour into Sussex” on a mission to secure the freedom of two black families, though in 1803 he recorded his displeasure at the task, writing that he had engaged in the “irksome” task of “abolition business most of the afternoon.”39

In addition to individual meetings, Hunt attended religious services held by Burlington Friends for free blacks where they participated in both religious conversations and discussed the latest abolition news, which made them part of the abolition process and gave them power to take action to ensure freedom for themselves and their families. At one 1796 meeting, for instance, the organizers read information on the state of abolition in the North from the PAS, which the blacks in attendance discussed. Hunt remarked that one black attendee, Hannah Burros, took center stage and explained New Jersey’s complicated relationship with slavery to the others. Hunt seemed to think very highly of Burros, visiting her seven months later after she fell ill. Hunt wrote that she was “quite deranged and [had] lost her reason” and that he became emotional at her “sorrowful condition,” praying for her recovery.40

These local Quaker meetings also sought to help educate West Jersey’s free black population to show whites that blacks could learn and were worthy of freedom. In a 1790 letter to Quaker abolitionist William Dillwyn, Susana Emlen claimed that several night schools that taught “the Negroes reading, writing, and arithmetic” had recently opened in Burlington as a way “to atone in some measure for the wrong they have suffered.”41 The schools, opened between 1789 and 1791 by the Burlington Quarterly Meeting, joined those already operated by the Upper Springfield Monthly Meeting. Similarly, Salem Quarterly Meeting in 1790 solicited donations of funds to create integrated schools for both poor white and black children. By 1793, the funds raised by those Quarterlies funded the creation of three schools in southwest New Jersey, with another opening in 1794, all controlled by Quaker educators who taught an integrated student population.42 Likewise, Philadelphia’s Free Black School assisted Trenton Quakers form a larger school to teach reading, writing, and arithmetic in evening classes year round to the city’s black adults. It copied the structure of the Burlington School Society for the Free Instruction of the Black People, formed in 1790, with both struggling against negative perceptions of their students by local whites. For example, in 1793, the Burlington school’s leadership complained that it had encountered many who thought blacks too ignorant and unworthy to educate.43

The Quaker interest in manumission and education led hundreds of slaves to escape slavery but also gave ex-slaves allies to help develop their lives in freedom. Even though some Quaker efforts were undoubtedly paternalistic, freed slaves took advantage of them to create independent households and thriving businesses. One such ex-slave, Cyrus Bustill of Burlington, owned a profitable bakery that sold flour, cakes, bread, and biscuits to local residents and those who travelled on the Delaware. Eventually, Bustill and his family moved to Philadelphia, where he attended Quaker meetings, belonged to the Free African Society, and taught in a school for freed slaves before his death in 1806. Like Bustill, Samson Adams, an ex-slave from Trenton, sold soap, which enabled him to buy a house in town and employ a housekeeper. Surviving records indicate that he had made a number of alliances with whites; almost fifty Trenton residents donated labor, supplies, or money to help him complete his home. The records reveal that Adams traded soap, food, and other goods with blacks and whites throughout the region. At his death in 1792, Sampson had accumulated a substantial personal estate that he divided among his family, with two white customers serving as his executors.44

* * *

Jersey Quakers had quickly realized that they needed an organization to coordinate their abolitionist activities and therefore latched onto the PAS, the most prominent abolitionist group in the United States. Sixteen of the original PAS members lived in New Jersey, many of whom prosecuted cases on behalf of the society. For example, Richard Waln, an affluent Monmouth County Quaker, communicated frequently with PAS leadership in Philadelphia and, as one of its founding members, helped free numerous blacks unlawfully held in bondage. In 1788, for instance, Waln intervened in the case of a Jersey child held as a slave even though his mother had been freed before his birth. Waln and the PAS, like most gradualists, believed litigation was the best avenue to defeat slavery. However, by early 1793 even Waln cited the lack of interest in abolition and the need for a more organized response to slavery in New Jersey. After Trenton PAS member Isaac Collins, who had done much legal work for slaves, ended his membership in the society, Waln lamented that a larger state network would be needed to fervently advance abolitionism.45

Years of communicating with members like Waln had convinced the PAS that it needed to create an autonomous society in New Jersey. In January 1793, a committee formed to organize a New Jersey abolition society and by April they reported that they had founded the New Jersey Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, headquartered in Burlington. The collaboration between the New Jersey society and the PAS continued as members from both organizations routinely exchanged information about specific cases.46 The newly formed society used the Declaration of Independence’s doctrine that “all men are created equal” to find fault with the state for withholding the principles of “justice . . . life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” from “an unfortunate and degraded class of our fellow citizens.” This rhetoric, of course, had been used by other abolition groups throughout the Mid-Atlantic. For instance, Presbyterian minister Samuel Miller of the New York Manumission Society argued that “any civilized country . . . [should] oppose . . . slavery,” especially in “this free country” where “the plains . . . are still stained with blood shed in the cause of liberty” and “the noble principle that ‘all men are born free and equal’ ” reigns.47

Quakers joined the new society en mass and dominated membership in at least five county-level auxiliaries. In Burlington, for instance, Quakers made up 70 percent of the sixty-five total members, while in Gloucester they represented 40 percent of the membership. In proslavery East Jersey, all but four of the members of the Middlesex/Essex chapter came from the Society of Friends and the Hunterdon County chapter even met at the Friends’ Meeting House. The society therefore became the arm of Quaker abolitionist outreach.48

The society continued to provide legal support for slaves and, led by former state attorney general Joseph Bloomfield, widely distributed previous New Jersey Supreme Court decisions to ensure their use as precedent in freedom cases. In one such case, Frank, a free black Middlesex County resident, had contracted with his wife Cloe’s owner, Issac Anderson, in 1778 to purchase her for the sum of 180 pounds. Now both free, the couple had a child, Benjamin, but then separated. By 1803, medical issues prevented Cloe from supporting herself or her son. The local overseers of the poor followed state law and charged Issac Anderson for Cloe and Benjamin’s care as her former owner. Less than a month later, Cloe died, which left Anderson supporting Benjamin. Because Anderson supported him, he believed Benjamin to be his slave. Applying precedent from previous cases, society lawyers sued Anderson and claimed that Benjamin, now twenty-one, had been born free because Cloe’s owner had manumitted her before his birth. After an intense legal battle, Anderson finally agreed that he did not have the right to hold Benjamin but demanded $150 in payment for his expenses related to Benjamin’s upbringing. After some negotiations, the society agreed to pay Anderson the $150 to ensure Benjamin’s freedom.49

Abolitionist lawyers routinely faced staunch opposition from those who attempted to hold onto their slaves through duplicitous means. In the case that provided the legal precedent for Benjamin’s freedom, Joseph Bloomfield argued in 1790 for the freedom of Silas, a child born after his mother, Betty, had been freed in her master’s will but served that master’s family under a fifteen-year indenture. The owner of the indenture, James Anderson (no relation to Issac Anderson above), claimed that since Betty had not yet been freed, her children should be considered slaves. Bloomfield countered that Betty gained her freedom at the moment of her master’s death but remained under contract for fifteen years. He successfully argued that any child born during an indenture subsequent to manumission would be free from birth.50

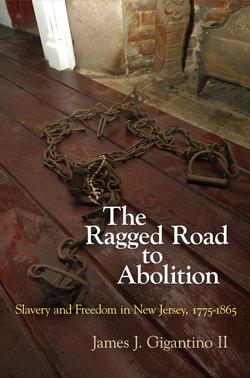

Figure 2. This Membership Certificate of the New Jersey Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery illustrates how white society members saw themselves as bestowing liberty to the enslaved.

Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

The increased presence of abolitionists in New Jersey motivated slaves to take action themselves to press their freedom through the courts since they now had allies who could assist them. Cuff, a slave from Somerset County, had been promised freedom by his master, Gilbert Randolph, either at his own death or when his son, James, came of age. However, when James came of age, Randolph reneged on the agreement and demanded ten additional years of service. Cuff, likely hearing of the court cases proceeding across New Jersey, absconded from his master and eventually convinced abolitionist lawyers to take up his case, one that won him his freedom.51

Abolitionist lawyers also filed suit to protect free blacks from being kidnapped and sold south, thereby limiting the illegal slave trade that thrived along the coast from New Hampshire to Georgia. For instance, in May 1803 the society’s lawyers litigated a case involving the sloop Nancy, owned by Ruben Pitcher, which had left Boston with four free blacks shackled in its hold. All had been held for debts, some as small as six dollars, in the Boston jail. Pitcher paid their debts and arranged for them to work off that debt on his farm on Martha’s Vineyard. A few days later, Pitcher loaded the four onto the Nancy and set sail for Savannah to sell them as slaves. Pitcher docked in Egg Harbor, New Jersey, for provisions, where the four blacks seized the opportunity to escape and fled to local abolitionists who arranged for the Nancy’s confiscation and their freedom. In a similar case, William Griffith, the future president of the society, arranged for the purchase and manumission of Charlotte, a Monmouth County slave whose owner had planned to sell her illegally to the West Indies.52

Outside the courtroom, the society lobbied legislators and participated in abolition conventions designed to address black freedom on a national level. In 1794, the society sent Joseph Bloomfield to a Philadelphia abolitionist convention, which elected him president. The convention called on Congress to halt the slave trade, arguing that its end must occur in order to “vindicate the honor of the United States, the rights of man, and the dignity of human nature.”53 Upon returning to New Jersey, Bloomfield and the society used these ideas of universal justice to argue that New Jersey needed to enact an abolition plan to fulfill the nation’s revolutionary promise. Society members told the state legislature that “natural feelings of the human heart . . . acknowledged by Americans in their act of Independence, as among the most undeniable rights of man” demanded that the state assist in freeing enslaved blacks.54

Bloomfield used this tie between revolutionary freedom and abolition as the main vehicle to support black freedom. Under his leadership, abolitionists gathered dozens of petitions to show that whites wanted abolition. These petitions, signed mainly by society members and Quakers, called for an end to “heredity human bondage” in the state by using the “great principles of justice and truth” from the Revolution. This Enlightenment rhetoric and revolutionary ideology would ensure that “common rights and happiness” be granted to all New Jerseyans.55 On a personal level, Bloomfield firmly believed in this logic, arguing in a 1795 letter to Philadelphia merchant Samuel Coates that in a state whose laws “proclaim liberty and happiness to all her citizens,” slavery could never survive.56

Like gradual abolitionists in other states, few society members believed in black equality; racism still dominated New Jersey’s abolitionist discourse and limited actions that alleviated the social and economic rift between free blacks and whites. In some cases, the society even opposed funding programs that supported free black education and instead focused their attention solely on slavery’s destruction. For example, in 1796 the society forced its Gloucester chapter to recall funds earmarked to educate black children. Even in the society’s pleas to the legislature, it targeted only the legal institution of slavery instead of improving free black life. The society claimed its members could be “consoled with the reflection that in a course of years, slavery would cease with the lives of those who now endure it,” but few tried to advocate for either immediate abolition or for a wholesale change in the way that whites saw blacks. Indeed, on the eve of gradual abolition, society president Griffith claimed that the phrase “in New Jersey, no man is born a slave” should be the mantra of abolitionists. The society’s primary goal remained gradual legal abolition.57

Overall, the society was largely ineffective at advancing abolition statewide. In 1798, it tabled action on several petitions and court cases due to the “the scattered situation of the Society and the extreme difficulty of forming efficient cooperation in those parts of the state where the necessity is the greatest.” Three years later, in 1801, the lack of abolitionist support forced Bloomfield to report to the National Convention of Abolition Societies that “the scattered situation of this Society occasions many embarrassments and difficulties . . . [as] members . . . are often so far apart as to render it impracticable for them” to work together. Thus, the society was never as powerful as societies in Pennsylvania or New York. Jersey abolitionists struggled to coordinate branches across the state without a large commercial center to organize around. The society also received little support from residents in East Jersey, where the majority of the slaves lived and legal cases were heard. The dearth of active East Jersey members and the overabundance of members who happily talked of abolition in counties with few slaves caused difficulty in actually ensuring that the society’s efforts reached those who needed them the most.58

* * *

Though white abolitionists believed their efforts had made great strides, New Jersey’s slaves and free blacks worked equally hard to negotiate for the liberties that they had heard about since the first dissent arose between Great Britain and the colonies. In the Mid-Atlantic, blacks published several freedom petitions, following the lead of New England blacks. For example, in 1800 Philadelphia free blacks wrote to congressional leaders to highlight the Revolutionary antecedents of abolition, claiming that abolition shared much in common with “our struggle with Great Britain for that natural independence to which we conceived ourselves entitled.”59 Similarly, three Connecticut slaves argued in 1797 that they were “in a much worse situation than we were in before the war,” even though Americans had defeated “the tyrant king of Great Britain” who “assumed the right of depriving all the Americans of their liberty!”60

In New Jersey, Revolutionary ideas encouraged slaves to actively seek out freedom themselves, most commonly by running away. However, absconding declined from its high watermark during the Revolution since slavery’s growth in East Jersey made community and family connections easier. In Bergen County, for example, the average distance between slave-holdings dropped from 3 to 1.5 miles by 1800, which allowed slaves to marry in greater numbers and create families that tied them to their local communities. As opportunity and desire declined, New Jersey newspapers printed 40 percent fewer runaway advertisements between 1784 and 1803 than during the Revolution, averaging 5.8 advertisements per year. Young male slaves continued to make up the majority of runaways, with a median age of twenty-five years. These fugitives deprived Jersey slaveholders of essential laborers to repair the state’s economy after the Revolution. As expected, most runaways (86 percent) came from East Jersey, though even this number represents a fraction of the likely total number. Circumstantial evidence, including Niemcewicz’s account of the Elizabethtown jail teaming with runaway slaves in a year in which only one fugitive advertisement appeared, indicates that runaways remained somewhat prevalent in the late eighteenth century.61

Though slower than during the Revolution, abolitionist activity in the 1790s encouraged slaves to abscond from their masters. One such slave, James Alford, left his master’s Rahway farm in 1794 and headed toward Pennsylvania because, as he described years later, he had heard a divine voice that told him he would soon be free if he sought assistance from local Quakers. Sneaking off the farm to the local Quaker Meeting House, Alford met several abolitionists who taught him how to read and write. He discussed with them at length the divine voice he had heard. After his escape, Alford’s master accused the local Quakers of encouraging him to flee.62

Abolitionism exacerbated the long-held white fear of slave rebellion, leading some masters to negotiate with their slaves to stave off revolt. Newspapers reported vivid firsthand accounts of the bloody rebellion in Saint-Domingue while refugees and their slaves simultaneously spread news of the revolt to American ports from Maine to Georgia. Jersey abolitionists claimed that Francophone settlers and their slaves had migrated to Philadelphia in droves, many of whom eventually settled in West Jersey and dramatically increased the region’s slave population. In Nottingham, for instance, almost half of the city’s forty-five slaves belonged to new French settlers.63 Likewise Susanna Emlen, writing to William Dillwyn in 1792, reported on “a new class of inhabitants in Burlington—a number of those unfortunate Islanders whose slaves have risen and made so much disturbance and valuable effects.” Emlen was surprised by both the large number of new slaves and that many of them had actually helped save their masters’ lives during the rebellion. However, she believed few could “wonder [why] their slaves should demand and forcibly take what had so cruelly been withheld from them.”64

The same almanacs and periodical literature that had encouraged white New Jerseyans to see blacks as inferior and animalistic now began to disparage the Saint-Domingue rebels. Bryan Edwards’s Historical Survey of the French Colony of St. Domingo pointedly accused abolitionists of starting the revolt. New Jerseyans, from their Atlantic connections, learned much from Edwards’s book about the dangers of slavery. They sought to protect themselves from a similar rebellion. In 1794, even local abolitionists warned that a general insurrection much like that of Saint-Domingue could occur if abolition did not begin soon.65

To prevent rebellion, both New York and New Jersey further limited slave movement and communication, and curtailed activities conducted without white supervision. New York banned gambling and the use of lanterns to limit arson, while Newark prevented slaves from meeting together or leaving their masters’ home after ten o’clock at night. Despite these regulations, the mid-1790s saw mysterious fires break out up and down the Atlantic coast, which exacerbated worries of slave revolt. In New Jersey, investigators believed that slaves in Newark and Elizabeth had planned to set fire to the two towns and launch a massive uprising. Other potential revolts, such as when Middlesex County executed three slaves for planning an uprising, upset already anxiety-ridden New Jerseyans.66

In addition to the threat of slave revolt, masters faced the possibility that their own slaves could injure them or damage their property. For example, Margaret, a mother of five, burned down her New Barbados master’s barn, while Nance poisoned her Sussex County mistress’s coffee with arsenic, and Sam, a slave owned by Newark’s Caleb Hetfield, stood accused of raping Mary Russel in 1785.67 Crimes like these led Bergen slaveholders to complain of the “many atrocities, acts of burglary, arson, robbery and larceny which have been committed by slaves in this County and this frequent running away from masters.” They demanded state officials pass stricter laws to preserve slavery.68

However, the fear of revolt, running away, and the increased abolitionist activity encouraged whites to more readily negotiate with slaves for freedom and for better conditions within slavery. The growth of slave communities in East Jersey was certainly a result of successful negotiations between masters and slaves. Slaves took advantage of revolutionary rhetoric and abolitionist agitation to argue for their own benefit. In this way, the nature of slavery slowly began to change as masters understood the limits of slavery in the early republic. These changes cushioned gradual abolition’s eventual blow as masters continually sought ways to sustain slavery within the institution’s changing framework.69

* * *

By 1800, Jersey slavery had grown despite assaults from abolitionists, fears of slave rebellion, and the constant ring of revolutionary freedom. New Jersey stood alone as the only northern state without a gradual abolition law, separating white New Jerseyans from other northerners who had begun to think seriously about slavery’s place in the developing nation. An 1803 pamphlet concerning the death of a slave from Saint-Domingue confirmed this difference as the author noted that New Jersey law “authorized his master to remove him as he would a piece of furniture” unlike the rest of the North.70 New Englanders especially used slavery as a way to contrast a free “North” against a slave “South,” with New Jersey fitting into neither region. As historian Matthew Mason claims, “the North was proud to denominate itself as the ‘free states’ in an ideological world that proscribed bondage as immoral.” White New Englanders saw themselves as fundamentally superior to southerners; their identity was based on the embrace of revolutionary freedom which, in their minds, proved their superiority. As New Jersey had yet to abandon slavery, it could not join this imagined morally superior “free” community, nor did many in the state desire to. Slavery still remained an important institution.71

The fascination with a “free” North began at the Constitutional Convention when regional distrust and differences based on slavery became readily apparent. James Madison famously claimed that the states diverged on issues “not by their difference of size . . . but principally from the effects of their having or not having slaves.” Madison believed the main problem in forming a new government lay not in a debate over large versus small states but “between the Northern and Southern” as the “institution of slavery and its consequences formed the line of discrimination” between the two regions. Of course, differences of scale had always existed between the South’s slave societies and the North’s societies with slaves. But since Massachusetts had outlawed slavery and Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island had all passed gradual abolition laws before the convention, the development of “free soil” led southerners to believe that New York and New Jersey would soon follow suit and the idea of a homogenous North opposed to slavery was born.72

Northerners at the convention did not make it difficult for southerners to see the North as a distinctively free region since northern delegates identified slavery as the root of the new nation’s evil. Rufus King, an adamant Massachusetts abolitionist, claimed that “the people of the Northern States could never be reconciled to” the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade. Pennsylvania’s Gouverneur Morris made the comparison even starker when he claimed that slavery “was a nefarious institution . . . the curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed.” Morris boldly challenged southerners to “compare the free regions of the Middle States, where a rich and noble cultivation marks the prosperity and happiness of the people with the misery and poverty which overspread the barren wastes of Virginia, Maryland, and the other States having slaves.” Morris’s language harkened back to the colonial ideal that the Middle Colonies, Pennsylvania in particular, had always been “the best poor man’s country.” There, “noble cultivation” and hard work could make everyone successful, in stark contrast to the South, where slavery had corrupted whites and divorced them from productive labor.73

Though Morris acknowledged, at least tacitly, the Mid-Atlantic’s ties to slavery, he made sure to highlight that northern slavery was not as harsh as the southern institution. He claimed that when crossing into “New York, the effects of the institution become visible. Passing through the Jerseys and entering Pennsylvania every criterion of superior improvement witnesses the change. Proceed south and every step you take through the great region of slaves” extenuates the dissimilarities between North and South. Morris believed that southern slavery was “so nefarious a practice” that it could never be equivalent with the institution in the North.74

Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman likewise argued that slavery in the North was intrinsically different by highlighting that abolition had commenced and “that the good sense of the several States would probably by degrees complete it.” Fellow Connecticut delegate Oliver Elsworth latched onto the idea of “good sense” and argued that “slavery in time will not be a speck in our country. Provision is already made in Connecticut for abolishing it and the abolition has already taken place in Massachusetts.” Elsworth also believed that free labor would expand and replace slavery, further strengthening the North’s economic strength and separating it from the South’s dependence on slave labor.75

Even as northerners tried to separate themselves from southerners, both shared a common belief in black inferiority. New Jersey’s William Paterson offered that he “could regard negro slaves in no light but as property. They are no free agents, have no personal liberty.” Likewise, Morris contended that “the people of Pennsylvania would revolt at the idea of being put on a footing with slaves.” These arguments, while underscoring the hypocrisy of making slaves both persons and property during the three-fifths compromise debate, represented the widespread view that blacks were not equal to whites.76

The combination of sectional differences in the convention and abolition’s success in New England and Pennsylvania convinced many Jersey abolitionists that slavery’s days in New Jersey were numbered. Joseph Bloomfield linked abolition to economic opportunity in an attempt to persuade New Jerseyans that slave labor actually hurt the economy. He claimed that New Englanders “by their enlightened” abolition policy and their employment of “the labor of freeman instead of slaves are daily obtaining advantages over the southern states.” The South, in their maintenance of the “injustice and immobility of their citizens in the unnatural and cruel treatment of their fellow men,” prevents them from an adequate “competition” with “the freeman.”77