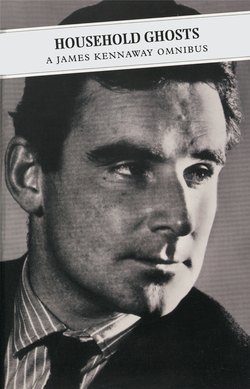

Читать книгу Household Ghosts: A James Kennaway Omnibus - James Kennaway - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеOf that familiar litany of Scottish literary talent cruelly cut down at the age of greatest promise, the case of James Kennaway is stranger than most. When he was killed in a motorway collision in 1968 at the age of only forty, he had already achieved that distinction rare in Scottish literature: an oeuvre which can truly be termed ‘complete’, even though fate decreed that two of his novels were destined for posthumous publication. It was a remarkable legacy for this most anguished of twentieth-century Scottish novelists, and yet a satisfactory sense of aesthetic completion eluded him right up until the tragic, and seemingly predestined, end.

Kennaway’s striving for a perfection of fictional form and style was as worthy of any modernist icon for whom pursuit of the ‘pure’ novel was a quasi-religious vocation. Each of his six novels took a progressively more indirect and sophisticated approach to narrative technique, culminating in the almost shocking minimalism of the posthumous Silence (1972). For all the novels’ formal variations, however, the constants are clear: intensely vivid characterisation, a powerfully visual quality of narrative, and a consummate control of highly sophisticated dialogue. Thematically, their common ground is that of power relationships in the institutional contexts of family, class and nation. Kennaway’s characters are riven by divisions, inflicted and self-imposed and the theme of entrapment, both literal and metaphorical, weaves a bright strand throughout his fiction. His fascination with individuals who are torn between the imperatives of idealistic yearning and social and moral restraints locates his fiction firmly within a Scottish tradition, though only two of his novels were ever set in the land of his birth.

After the remarkable success of his debut Tunes of Glory in 1956, Kennaway asserted, somewhat testily, that he was ‘a novelist from Scotland, and not a Scottish novelist’.1 Like his contemporary and fellow creative exile Muriel Spark, Kennaway’s tangential relationship with ‘a Scottish formation’ is a continuing enigma, and his own distinction – shared by many Anglo-Scottish writers – is a salutary one for a country which must be ever more mindful of the dangers of herding its creative pedigree into cosy ethnic enclosures. Tunes of Glory and Household Ghosts are haunted by a gallery of horribly familiar native spectres – division, defeat, and denial to name but three – but it is also important to be aware of forces within these novels which struggle towards absolution from a nation’s cultural pieties.

Modelled closely on the author’s own bittersweet experiences of army life (he served as an officer in the Cameron Highlanders), Tunes of Glory was an extraordinarily accomplished fictional debut, and remains the finest literary exploration of Scottish militarism – a subject which has received surprisingly scant artistic attention, given its hardly insignificant impact on the nation’s historical trajectory and self-image. The novel remains Kennaway’s most accessible, and its popular reputation was consolidated by the film version of 1960, directed by Ronald Neame. Kennaway’s own flawless screenplay for the film is testimony to the luminous characterisation and visual power of the original text.

The implications of the novel surpass the starkly simple dynamics of the conflict that forms the centre of its drama. Not for the first time, Kennaway takes unprepossessing, if not banal, material and mines from it undetected depths. The barrack-room-boy braggadocio of the swaggering and aggressive Jock Sinclair – a soldier’s soldier fuelled on whisky and a fading reputation for wartime heroics – is brought into self-destructive confrontation with the intro-verted and ineffectual, but seemingly privileged, Eton and Sandhurst officer Basil Barrow, who arrives to depose the working-class, ex-ranker Jock as the new Colonel. The ensuing psychological conflict engineered by the resentful Jock is a sublimated war between two cultures fuelled by class prejudice. This is not just a rehearsal of stale Scottish grievance versus complacent English insensitivity, however, for the novel’s deceptively straightforward narrative subverts the anticipated tragic outcome.

When Jock plays into Barrow’s hands by striking a corporal piper he finds with his daughter, it appears that the former will capitulate first. But it is Jock who finds the endurance to sustain himself long enough to undermine, cynically, Barrow’s inability to take decisive action against him through fear and repressed admiration. Incapable of bearing the psychological strain, Barrow shoots himself. Jock, in turn, finds that the pity and shame suppressed in Barrow have now been awakened in himself. In the closing chapter, in twenty pages of great brilliance, Jock’s hyperbolic funeral orders for the dead colonel are both a moving threnody for the sacrifice of all soldiers, and a mock-heroic deconstruction of the militarist ideology which drags Jock into his final and inexorable mental collapse.

The tragic irony of the novel is that the two protagonists are each destroyed by their inability to comprehend the one virtue they might be said to possess: fear. Within Barrow’s brittle inability to destroy the fellow soldier whose heroism he admires there resides an incipient humanity, which the military code cannot sanction. Conversely, it is Jock’s dawning fear that his very identity as a wartime hero and leader of men is incompatible with the constraints of postwar society, which finally consumes him.

It is no coincidence that Tunes of Glory was published in the year of the Suez Crisis, the humiliation of which effectively symbolised the end of Britain’s aspirations as a post-imperial world power. As an anatomy of the dichotomies and hypocrisies festering within Scottish society – telescoped within the claustrophobia of barrack life – Kennaway’s ruthless grasp of moral irony closely resembles that of his other great contemporary, Robin Jenkins. But Kennaway goes further. In a post-feminist context, it becomes possible to re-read Tunes of Glory as a disturbing study of masculinity itself in crisis. The novel has been faulted for giving its women characters scant treatment, but this is missing the point: the role of women as an ‘absent presence’ throughout the text acts as a metaphorical symptom of the very condition the novel seeks to anatomise.

In Jock’s aggressiveness and Barrow’s passivity we find two irreconcilable forces akin to the ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ principles at war in the male psyche. Absent women figures play a key role in both Jock’s and Barrow’s respective dysfunctions. The reason for Jock’s status as a single parent is left tantalisingly unexplained, whereas Barrow’s recent divorce is clearly implied as a major factor in his instability. Jock’s relationships with the novel’s two women characters – his daughter Morag and his mistress, the failed actress Mary Titterington – both founder on the rocks of male sexual jealousy, and their breakdown ultimately precipitates the events of the tragedy.

Less straightforward are the not infrequent hints of homoeroticism which ripple through the text. It is present in Barrow’s repressed ‘love’ for Jock’s heroic past and Jock’s ritualised and theatrical final tribute to Barrow; it is present as farce in the parodic spectacle of the soldiers dancing with each other in the opening chapter, and it will re-surface as tragedy in a crucial episode in the novel, when Jock and Mary arrive at a moment of short-lived mutual understanding and redemption in the symbolic confines of her dilapidated theatre dressing-room. Mary’s agonised confession of her love for Jock contains the novel’s most candid allusion to the repressed sexual ambiguity which Jock is unequipped to acknowledge:

He held her stiffly, and with hard lips he kissed her brow, by the border of her hair. He asked innocently, ‘Are you saying that you love me, Mary?’

It was agony for her. ‘Jock, of course I am. Of course I am. Like any other woman that’s ever known you,’ she said and she looked up at him for a second. ‘And I’m no sure it isn’t every man, too.’

He laughed at that. He tried to make it all a joke. ‘Here, here, now. That’s a very sophisticated sort of notion. That’s too complex for me.’

Earlier, she has told him: ‘… it’s you that doesn’t see the half of your men’, in an exchange where she cannot decide whether Jock is ‘a child’, ‘a lovely man’, or ‘a bloody king’. Jock cannot see the other potential ‘half’ of himself, only the reflection of the ‘sad soldier’ reflected in the mirror in the couple’s final embrace. The sad soldier is conditioned through the military code to suppress the ‘lovely man’ through a ‘childish’ reflex to order and control the world as the ruler with blood on his hands. It is as much Barrow’s predicament – the other missing ‘half’ in the mirror in this psychologically and symbolically dense scene – as Jock’s.

The subtextual gestures towards issues of gender and sexuality in Tunes of Glory suggest a prelude to Kennaway’s more direct approach in the subsequent novels, where decisive, and assertive, women characters suddenly occupy centre stage. Mary Ferguson’s tortured quest for fulfilment is at the centre of the classic Kennaway love-triangle in Household Ghosts (1961), the novel that reveals most about the author’s ambivalent perspective on his Scottish background and shows an increasing attraction to allegorical frameworks. The household in question is that of a decaying aristocratic Perthshire family whose fortune rests precariously upon the ‘ghosts’ of past disgrace and degradation: the shadow of widowed Colonel Ferguson’s past indiscretions, and his late wife’s lurid working-class past and alcoholic self-destruction.

The combined legacies of myth-making and dysfunction haunt and control the destinies, and relationship, of son and daughter – Charles Henry Arbuthnot Ferguson, known, unforgettably, as ‘Pink’, and Mary, whose turbulent relationships with her impotent husband Stephen and her lover David Dow drive a spare and brittle narrative which contains some of Kennaway’s most taut writing, much of it in anguished and nervous dialogue. Once again, the plot centres on rivalry and self-deception. The central struggle is between the ruthless and self-confessed Calvinist scientist David, whose accusatory and amorous letters to Mary form a subsidiary narrative, and the strangely allied Pink and Stephen, for the love of Mary. ‘They christened her Mary. I cast myself, perversely, as Knox’: David attempts to drive a fissure between Mary and her complex loyalties to the nursery world of parody, mimicry and private language to which she and Pink escape in denial of their destructive behaviour, and their probable incest (implied with extreme subtlety), and to her collapsing marriage.

The effect on the self-effacing Stephen is abrupt: he attempts suicide. It is in the sophisticated portrayal of Pink’s gradual disintegration into dipsomania and drying out in ‘a baronial nut-house’, however, which is the novel’s triumph. As his emotional hold on Mary weakens following their father’s death and the fabric sustaining Pink’s dependency collapses, the writing fluctuates between increasing extremes of tortured parody and barely repressed mania, culminating in Pink’s final bathetic invocation of Rousseau’s last words as he is driven off to the nursing home: ‘T-tirez la whatsit, Belle,’ he said. ‘La farce est jouée.’ Pink is a brilliantly original creation, and he is also the author’s most consummate fictionalist in a novel whose principal concern, paradoxically, is the deadly power of invention itself.

While Household Ghosts wears its archetypal trappings of Anglo-Scottish tensions lightly, it amounts to a disturbing vision of a Scotland so inimical to transcendence that imaginative escape is both inevitable, yet inevitably thwarted. Pink’s, but also Scotland’s, ‘predestinate tragedy’, the novel finally warns, is to be doomed to the plight of ‘the permanently immature’. Only in Mary’s final ability to settle for compromise does this bitter novel offer a glimmer of light.

In a wilfully accelerated and frenetic career, the next seven years saw Kennaway produce a further six novels, a play, and numerous notable film screenplays. He had completed a fourth draft of the novella Silence just days before his death. It is a shocking and startling coda, and so compressed and pure a narrative that one wonders how the author could possibly have followed it. The scale of the work belies the enormity of the subject it tackles: racial violence in urban America. Kennaway’s bittersweet years in the USA as a scriptwriter were to find an extraordinarily potent artistic distillation.

Silence represents the ultimate refinement of the author’s fascination with the dynamics of power. Larry Ewing, a mild-mannered white doctor, finds himself ineluctably drawn into a mission of self-appointed revenge following the ostensible assault of his daughter Lillian by a black youth. The deputation into the ghettoes of Harlem by Ewing, his son, son-in-law and professional associates goes disastrously wrong as a race riot erupts, in which his son, it is subsequently learned, is lynched. Suffering from a stab wound, Ewing flees and takes shelter in a dilapidated room, only to discover that he is not alone. It is inhabited by the near mythical, Amazonian figure of a dumb black woman – named ‘Silence’ – who first abuses, but then protects, contrary to her own prejudices, her traumatised captive.

Kennaway’s fixation with entrapment reaches its peak. The confined couple develop an intense relationship by turns tender, violent and childlike, playing out a sequence of allegorical pairings as Madonna and child, Adam and Eve, Christ and crucifier. In the revelation of their shared humanity, Ewing’s fundamental beliefs and his very identity are challenged, to the point that when he discovers that Silence is implicated in his son’s murder, his love for her supplants grief and hatred. When their retreat is discovered, Silence assists Ewing to escape, but recognising the enormity of her sacrifice, he returns to attempt to save her from her martyrdom to the black extremists who attempt to crucify her. The couple are eventually discovered by the police, who ironically laud Ewing as the avenging white hero. It is when Ewing realises that the authorities intend to torture Silence into ‘talking’ that he commits the final existential act of grace: a symbol of the revelation that ‘it is only in our impossible love for each other that we can defeat the carelessness of God.’

Few fictional attempts to come to terms with the enormity of racism can boast such a simple but apposite fusion of content and form as Silence. Marking the culmination of his increasingly woman-centred narratives, in Silence and her ambiguous inability, or refusal, to ‘utter’ her identity, Kennaway creates the perfect structural reflex for this ‘savage allegory’2 of the oppression which renders the powerless speechless or invisible. ‘There is a staggering strength in your silence. Believe me, the most magnificent pathetic protest of them all,’ Ewing concludes.

In a fashion which is strangely reminiscent of Tunes of Glory, the novella makes sophisticated use of symbolic polarities which might, in less artful hands, appear groaningly ponderous – in this case, the narrative’s shifting patterns of allusions to the colours black, white and red, whether it is Ewing’s blood on the snow, or his first glimpse of Silence’s otherworldly eyes. In this unrelentingly visual text, the elliptical Kennaway narrator seems to have finally vanished into ‘silence’ to be replaced with a rapid and laser-sharp lens. It is the organ of perception which is central not only to the action, but to the novella’s insistence – encapsulated in Ewing’s final devastating seven words – that at the core of racist ideology is how we choose to see.

Seldom can a posthumous work have been so poignantly named, nor its re-publication more justified. The novels gathered here, and the last in particular, will confirm the efforts of critics in the 1980s to afford this mercurial literary talent his due place in the tradition of twentieth-century Scottish fiction as one of its most surprising innovators. That he would have found his assured place within the Scottish literary canon a source of amusement (at best) or irritation (at worst) is all the more reason why we should continue to read him. As the parameters of that canon continue to be debated, Kennaway, it is hoped, will be reassessed not just within the context of his contemporaries, but as a precursor: a novelist whose obsession with form and language, intensely stylised and cinematic narratives, and sharp epiphanies of the Anglo-Scottish turns of mind anticipate contemporary fictional talents as different as A.L. Kennedy, Alan Warner, and Candia McWilliam.

Gavin Wallace