Читать книгу Modern Japanese Print - Michener - James Michener - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

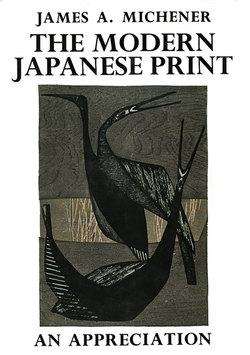

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

I N the early summer of 1959, business required that I be in Tokyo during an exciting time in my life: word kept trickling through from New York telling of the unexpected good things that were happening to a novel I had recently completed, and it looked as if it might be a success. For five years I had worked on the novel, and to have it accepted was encouraging, but the degree of success promised by these first reports went well beyond my expectation. Thus early in the life of the book I was assured that the time I had invested in its writing would be repaid; whether or not the public would like the book would be determined later.

As a result of the good news, I found myself assured of financial independence for a few more years, and I began to reflect upon how unfairly modern society distributes the rewards of art. I knew literally hundreds of able writers who found it impossible to earn a living, while to a few all good things happened. Once I myself had labored at writing for eight years without being able to earn a nickel, and I had been as good a writer then as I was now. Those who try to be artists exist in a world of nothing or everything, and I wish it were not so.

It was in this mood that I was drifting down Tokyo's Ginza one sunny afternoon, idly watching the flow of life along that enchanting thoroughfare. With nothing better to do, I turned west and passed into the warren of little streets and alleys known as the Nishi Ginza. Soon I found myself standing before a window I had grown to know; it belonged to the print shop and art gallery called Yoseido, opened in 1954 by Abe Yuji, third-generation representative of a family of art-mounters which had formerly been appointed to mount scrolls, screens, and the like for the Imperial Household and had also become prosperous in Ginza real estate. Ever since Yoseido's opening, the artistically-minded young Abe had served as the principal salesman for a group of artists who had made something of a splash in the art world.

I entered Yoseido that afternoon and saw on its walls the latest prints by artists I had come to know well. Here was a brilliantly colored alpine scene by Azechi Umetaro, and I studied the manner in which this delightful mountaineer had progressed to new understandings of his art. On the other wall was a marvelous, somber abstraction by Yoshida Masaji, a brooding thing of gray and black and purple, and again I lost myself in contemplating the various plateaus of progress across which this young man had moved in the years I had known him.

Also prominent was a large print in stark black and white, an architectural scene carved in the most ancient tradition by the oldest of the artists, little Hiratsuka Un'ichi, who had been my close friend for many years and who was still one of the greatest of contemporary woodblock artists, regardless of what country one was considering.

Here before me was the work which fifty men had accomplished in the two years since I had last met with them: the scintillating color prints, the vibrant black-and-whites, those done in the old style, and those so modern that they clawed at the mind for recognition. It was a body of magnificent work, one group's summary of how men saw the world and its passions.

As I looked at the prints I could see behind each one the man who had carved those blocks and pressed that paper down into the splashed colors. They were as fine a group of men as I have ever known: schoolteachers, mechanics, intellectual hermits, wild, gusty men who loved to drink, mountaineers, factory workers, poets of the most exquisite sensibility, laughing men, sober men, tragic men. And as I saw their faces staring back at me I experienced a real sickness of the soul, and out of that sickness came this book.

For I, by pure accident, worked in a field (writing) in a society (America) that assured me a decent income, a good living, and some security for the future. But those men on the wall, most of them with a far greater talent than mine, were laboring in a field (print-making) in a country (Japan) that provided only the most meager living, if any. Of all the woodblock artists I have known in Japan only two have been able to make a living from their art, and they have worked like dogs to accomplish even this. All the others have had to devote their principal energies to irrelevant jobs.

It has always seemed to me most unfair that a world which, whether it acknowledges the fact or not, requires art just as much as it requires rice has never discovered a way in which to reward the artist sensibly. A young American, talented to be sure, writes a book about a man who wears gray-flannel suits and from it earns more than a million dollars. Another young American whose equal talents run to poetry cannot even begin to make a living. A third young American with more talent than either of his compatriots turns to sculpturing and literally starves.

Or, to take a specific example, I spend five years at a major project and before it is even published I am assured security for two or three years, while Yoshida Masaji, in Tokyo, works for the same length of time on his statement of a major theme and from it gains almost nothing. Tormented by these injustices, I decided that the least I could do would be to purchase still more of the work of my friends; so I quickly bought all of their recent prints and lugged them back to my hotel room. There, with the help of a maid and a box of thumbtacks, I hung the prints until they completely covered my walls; and then I sat solemnly in the middle of the room to review what had been happening in Japan's art world since my last visit.

I was overcome by the beauty that these hard-working men had created. There was a richness and a variety that stunned me with its opulence, a warmth of comment that was constantly delightful; and I returned to the comparisons that had stung me in Mr. Abe's shop: why should my work be paid for so well and theirs so poorly? I thought: "When I consider what these men have meant to me, I'm almost obligated to do something." For some hours I pondered what to do; one could not simply share one's good fortune with no reasonable explanation, and I had already bought all the prints I could reasonably take home with me. And then an idea flashed into my mind: "Why not make a book so beautiful as to do credit to these artists? Each picture in it will be an original hand-printed work by one of them. Every penny the book earns will go back to the artists. And they'll be paid before the book is printed."

This was the proposal I made that same day to my long-time friends at the publishing house that has done more than any other in the world to introduce the Orient to the West—to Charles Tuttle, the canny Vermonter who had the foresight to expand the family business from its rare-book New England background to include a very active Tokyo publishing operation, and to his discerning Texas-born editor-in-chief, Meredith Weatherby. They studied for less than a minute before agreeing, and the fact that the book was ultimately published is due to their appreciation of what it might accomplish.

This explains the genesis of this book. But it does not describe why the book was worth doing in the first place nor the full debt of gratitude I myself, and doubtless many others, owe these artists.

It is not my intention here to write even a brief history of the artists whose work makes up this book. This has been ably done by Oliver Statler in his Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, which is a lively, informative essay crowded with good reproductions and was also published by Tuttle's. However, for maximum enjoyment of the prints that are to follow, it is necessary that the reader appreciate something of the historical derivation of the artists who did them and of the school that produced the artists.

Starting roughly in the middle of the seventeenth century, a group of Japanese woodblock carvers working in the two great cities of Kyoto and Edo (later Tokyo) branched out from their traditional task of carving illustrations for books and began issuing large single sheets which by themselves were works of art. Quickly the taste of the times required that these striking sheets be adorned by the addition of hand-applied colors. Rather later than one might have supposed, sometime in the early 1700'S, a device was perfected whereby colors could be applied not by hand but by block printing, but for nearly fifty years the resulting prints were limited to only two or three different colors, since registry of the colors from block to block was haphazard.

Even in these early days of the art a unique tradition characterized its technique: the artist drew the design, a woodcarver cut the blocks, a printer colored the blocks and struck off the finished prints. Invariably these jobs were done by three separate men. Sometime near 1765 the printers who worked with the famous artist Harunobu perfected a system which assured accurate registry for any number of blocks, and the great classic color prints, sometimes consisting of twenty different colors applied each from its own block, were possible. From this culminating period—roughly from 1765 to 1850—came the great names of Japanese color prints: Harunobu, Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai, and Hiroshige.

Magnificent work was accomplished by these men. Design was impeccable; color was subtle; execution was of a quality that has never been equaled. Starting in the 1820's, samples of the greatest previous work began filtering into Europe, and in the 1850's many leaders of the French impressionist school were already connoisseurs. The impact of Oriental prints upon the work of artists like Degas, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Matisse is well known. Gauguin writes that when he fled to the South Pacific he took along a bundle of Japanese prints. Without the lessons taught by the Oriental artists, some of the innovations perfected by the impressionists might have been impossible.

But by the beginning of the twentieth century the vitality of the classical school had dissipated, and although there were skilled workmen still trying to accommodate the old techniques to the burgeoning artistic ideas of a new Japan, and although a few fine prints were still issued each year, it was apparent to all that the art of the old-style Japanese woodblock was moribund.

In the early years of the twentieth century a group of experiment-minded young Japanese decided that if their nation was to achieve a vital art, its artists would have to develop new forms comparable to those that had swept the Western world. The impact of this thinking was greatest, perhaps, in the field of oil painting, but more fruitful, possibly, in the inspired work done by a group of woodblock artists, for in this medium the best of the old tradition—fine draftsmanship, excellent design, and the world's best woodcarving—could be preserved and wedded to strong new content. One firm principle was developed: in contrast to the classical system in which the artist merely designed the print, leaving the carving of the blocks to one technician and the printing to another, the newer print artists preached that the artist himself must do the designing, carving, and printing. A new term was devised to describe such a print— sosaku hanga, meaning "creative print," the characters for which have, incidentally, been used as a title-page decoration and are also repeated in the water-mark of the handmade Japanese paper in this book.

If one had to select one man who best exemplified these ideas, he might well choose Yamamoto Kanae (1882-1946), who studied in Japan, traveled widely in Europe, and issued a small number of prints that look as if they had been done by either Van Gogh or Gauguin. I have not seen all of Yamamoto's work, but so far I have never encountered any of his prints whose subject matter reveals that they were made by a Japanese. Almost singlehandedly he projected the modern print school into full international orbit.

The greatest artist produced by the school was Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955), a superb abstractionist who will ultimately stand beside European artists like Klee and Braque. Again, I cannot recall any of his important work that reveals in its subject matter any Oriental derivation. Onchi was an admirable artist, formed by the technical precepts of Yamamoto and the artistic impact of men like Munch of Norway, Kokoschka of Vienna, Van Gogh of Amsterdam, and Kandinsky of Berlin. His best prints are soaring poems reflecting the life of the spirit, and he set his imprint on an entire group of contemporaries.

But at the same time there were other artists who remained indifferent to Onchi's development, and these men worked out a much different approach to both art and subject matter. Hiratsuka Un'ichi, born four years later than Onchi, found that he was attracted to the simplified techniques used by the beginners of the classical school in 1650 and, using these antique processes, he began producing majestic prints in black and white. Connoisseurs quickly discovered how effective such work could be, and since Hiratsuka often chose for his subject matter the timeless architecture of Japan, his prints encouraged nostalgia.

Hiratsuka's technique was quickly adopted by the fire brand of the movement, Munakata Shiko (born 1903), whose rudely-carved Buddhist deities are the towering accomplishment of the black-and-white branch of the school. Better known abroad than Onchi, Munakata is held by most Western critics to be one of the most powerful artists working today.

After these two basic approaches to art had been established, a rich proliferation of technique and subject developed. As the prints in this book show, the contemporary Japanese print artist has the entire world of design to choose from, a subject matter that can be either traditional Japanese or avant-garde abstraction, a palette that ranges the entire color spectrum, and the freedom to use for his blocks any material that will yield a good impression: concrete, paper stencil, glass, realia such as leaves or shoe heels, hand rubbing, waxed paper, modern plywood, and, of course, the traditional block of cherry on which the classical prints were customarily carved.

In studying the work of this school we are watching a group of gifted artists who have been set free, who are no longer imprisoned in the conventions of one small island, and who have made themselves full-fledged citizens of the world. At the same time they remain the inheritors of a permanent tradition, and it is this interplay between the old and the new, between the inner world of Japan and the outer world of Paris, that makes the school so fascinating.

This modern school increases yearly, both in numbers and in versatility. I wish many more of its artists could have graced this volume. Aside from the ten here included and those great names already mentioned, I should like to list a few more who have particularly appealed to me; I can heartily recommend their work to the reader interested in seeing more of this exciting art:

HAGIWARA HIDEO (b. 1913) has produced a striking new kind of work which has won great favor from critics and public alike. With dark, iridescent colors superimposed upon flawless abstract design, he constructs prints that vibrate and give the impression of solid artistic control.

HASHIMOTO OKIIE (b. 1899) specializes in handsomely controlled depictions of Japan's medieval castles, done in great style, with commanding color. His prints are best when hung like Western oils.

HATSUYAMA SHIGERU (b. 1897). An illustrator of children's books, and one of the very best in Asia, Hatsuyama makes a few prints each year, but only as an avocation. They are the most poetic, the most unearthly, and the most subtly enjoyable of the work being done by the contemporaries. Like Klee, Hatsuyama has a private vision of the world, and his prints give exquisite fleeting glimpses of it.

INAGAKI TOMOO (b. 1902) has gained international notice for his highly symbolic studies of cats. An admirable draftsman, he catches the mood of nature in prints that are instantly attractive.

KAWAKAMI SUMIO (b. 1895). A wide audience has been built for his sardonic burlesques of events that occurred in Japan during the days when Europeans were first arriving with outlandish clothes and customs. These saucy prints are thoroughly delightful in a mock-archaic way.

KAWANISHI HIDE (b. 1894). His brightly colored scenes of circuses, harbor life in the port city of Kobe, and restful flower-decked interiors are marked by strong individuality both in palette and in flatness of execution. These are among the most colorful prints produced by the school.

KAWANO KAORU (b. 1916), starting much later than most of his contemporaries, began by issuing a series of prints which gained immediate popular acceptance. They show children caught up in everyday experiences yet depicted in a manner that is shot through with fantasy and loveliness. In any exhibition of contemporary prints, it is a safe guess that Kawano's portraits of children will sell first, his remarkable picture of an adorable little girl emerging from a snail's shell serving as his popular masterpiece.

KITAOKA FUMIO (b. 1918), having been born of well-to-do parents and educated in part in Paris, is probably the most sophisticated of the contemporaries. His prints excel in delicate coloring, firm control of design, and most pleasing over-all effect. He is unusual in that he works equally well in either representational or non-representational subject matter. I am very fond of Kitaoka's work and suspect that he will ultimately be judged one of the most satisfactory of the artists in this school.

MABUCHI THORU (b. 1920) has developed the most distinct technique used by any of the moderns. On flat boards he pastes little geometrical fragments of cigar-box wood until a mosaic has been built up. When blocks thus constructed are printed in strong, yet subdued, colors, the result is enchanting, a kind of pointillism in wood, a Seurat in Tokyo. His prints are big, more expensive than others, and artistically rewarding.

MIZUFUNE ROKUSHU (b. 1912). One of the most ornate styles being used today is that of Mizufune, who builds up on his prints a scintillating texture that is a delight to the eye. It has the quality of fine enamel work, but the simplicity of strong, rude art. When applied to the outlines of the fish that Mizufune often selects for subject matter, the result is positively brilliant. I am very partial to the unpredictable work of this fine artist.

NAKAO YOSHITAKA (b. 1910) specializes in powerful single figures carved with great style and with much attention to texture. They are boldly colored and create strong patterns when seen from a distance. He originally carved his blocks from wet concrete, which accounts for the striking texture of his prints, but recently he has learned to carve woodblocks so as to produce a comparable effect.

NAKAYAMA TADASHI (b. 1927). In design the prints of cranes done by Nakayama are refreshing, in carving superb, and in coloring highly individualistic, strong primary colors having been overprinted many times with flecks of subtly graded subsidiary colors until an ebb and flow is achieved which makes the print unexpectedly rich. The result is most decorative, and it is understandable why these pictures of cranes have become so popular.

ONO TADASHIGE (b. 1909). His finished work looks like a Norwegian or a post-impressionist German oil painting. Trained critics hold that his work is among the most impressive that Japan has to offer. Certainly it has more raw force than that of his colleagues, and anyone seeking diversity in his collection of Japanese prints should certainly consider Ono's work.

SAITO KIYOSHI (b. 1907) is one of those fortunate artists who have enjoyed both critical acclaim (many international awards) and also great popularity with the public (more prints sold overseas than any other modern). His powerful design, fine coloring, and interesting content covering widely scattered fields have combined to make him one of the finest working artists. Never static, he has progressed through many styles, always with distinction.

SASAJIMA KIHEI (b. 1906) has adapted the Munakata technique to the depiction of landscape, which he represents in brilliantly carved, complex, black-and-white designs. Patrons not informed in the arts usually pass Sasajima's uncompromising prints by; foreign museum directors visiting Japan for the first time almost always lug home a sheaf, for his artistic content is high.

SEKINO JUN'ICHIRO (b. 1914). One of the most successful of contemporary print artists, Sekino has issued a long series of portraits, architectural views, and theatrical scenes. One or two of the latter, in bold, twisting design, are among the best prints made in this period, his depictions of incidents in the puppet theater being the best.

SHINAGAWA TAKUMI (b. 1907). I am particularly fond of the work of this gifted abstractionist. He produces large, bright prints of great decorative value, stunning compositions with clashing colors and enormous vitality. I rarely see a Shinagawa that I do not like, and the more I keep them on my walls at home, the more rewarding I find them.

UCHIMA ANSEI (b. 1921). A native Californian but caught in Japan at the beginning of World War II, Uchima has developed into one of the subtler of the print artists. Working in an advanced nonobjective style, he creates tenuous poems in form and color which have been highly praised both in Japan and abroad.

YAMAGUCHI GEN (b. 1903) is perhaps the most international of the artists working today. His prints are of a high quality, few in number, poetic and mysterious in content. He is one of my favorites, a judgment that was confirmed when he won first prize in a world competition held in Europe. His subject matter is fantasy; his artistic mastery is superb.

YOSHIDA CHIZUKO (b. 1924). Wife of the artist who follows, this young woman has recently burst onto the print scene with an explosive series of ultra-modern compositions centering on the jazz world and its reflection in abstract art. Her prints are daringly designed and brilliantly colored. They form a distinguished if surprising addition to the Yoshida canon.

YOSHIDA HODAKA (b. 1926). Son of Hiroshi, brother of Toshi, and husband of Chizuko, this young man has a good chance of developing into the best artist of the family. He has a keen sense of design and is a fine colorist. He has vacillated between objective and nonobjective art but seems to be more at home in the latter style, in which he is continuing to produce prints of great distinction.

YOSHIDA TOSHI (b. 1911). Following in the footsteps of his distinguished father, Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950), who was the best-known of the traditional woodblock artists of his period and who traveled widely in the United States, Toshi has visited many parts of the world and has produced from his travels a series of handsome, interesting prints, those relating to the southwest United States being among his most effective.

It is not generally understood that often a worker in one field of the arts is indebted to men who have worked in wholly unrelated fields. Yet this is apt to be the case. To cite one obvious example, Romain Rolland could not have written Jean Christophe without the artistic instruction he had received from the world of music. In the field of Japanese prints Onchi Koshiro has told us of his indebtedness to European artists like Edvard Munch and Wassily Kandinsky, but he acknowledged an even greater debt to Johannes Brahms, with whom he felt a deep kinship.

My spiritual debt to the print artists of Japan is both deep and inexplicable. I was just beginning a writing career when I first met Onchi Koshiro, Hiratsuka Un'ichi, and their colleagues; so there was a freshness of morning in our association. The Japanese were older than I, more informed in the ways of art, and much more profoundly dedicated to a life of extreme hardship; but I was at a period of my development when it was of crucial importance that I encounter someone with a total commitment to the world of art, and in these Japanese artists I met such men.

I can recall my initial meetings with each of these gifted, almost childlike men. I can remember the powerful impact their work had on me, and how I derived a personal pleasure from their growth as I watched it unfold year by year, always with fresh impetus and newly invented delights. I remember with special acuity the wintry afternoon on which I first met Azechi Umetaro. The stocky little mountaineer, looking twenty years younger than his age, had just had a front tooth knocked out—how I speculated about that—and was only then beginning his adventures into the field of abstract art, which he explained to us with the fresh and winning lisp of a child. He unrolled sheaf after sheaf of new prints, and they were striking in their force and color. I startled Azechi by wanting to buy four copies of each of his latest works, because I wanted to have at hand examples of the manner in which a creative man varied his work from one printing to the next.

Later I came to know most of the artists of the school, and I acquired hundreds of their prints. There was a constant joy in returning to Japan and checking up on their accomplishment during my absence; and they, for their part, were pleased to discover what I had been doing while they were making prints. Often we dined together and I can recall one fine dinner at which some twenty of the artists convened at one of the old restaurants in the brothel section of Asakusa, where artists and intellectuals had been meeting for two hundred years, and in the flush of the night some rather expansive speeches were made. When it came my turn I said: "I won't see you for some years, but in that time you will all make a few more prints that will carry you a little closer to your goal, and I shall write a book or two which I hope will be good. We shall be a world apart, but we shall be working side by side, each helping the other."

Half of my mature intellectual life has been built around this group of men. I have written books which have helped carry their fame to the world; but I have received so much more from them than I have been able to give that at the present casting up of accounts I must owe them at least half of whatever I have been able to accomplish. Wherever I go, I keep their prints upon my wall so that I shall be constantly reminded of this debt.

It is important to record that my affection for this school of artists is neither capricious nor accidental. I did not stumble upon their prints with an untutored eye, to be bedazzled by the first bright art I saw. I served a long apprenticeship in European art and, had I had the funds when I lived so intimately amongst it, I would have collected Renoirs and Vlamincks and Chagalls and Chiricos, for my taste has always inclined that way. Also, before I saw my first contemporary Japanese print I had acquired a substantial collection of the old masterpieces done by classical artists like Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai, and Hiroshige. I was therefore schooled in both the best of European oil painting and the best of Japanese woodblock design.

But it was the impact of this bold new world of Japanese prints done in the full European tradition, yet combining many of the Oriental values of the past, that quite stunned me. I was at an age of my own development when I hungrily required such an experience, and it was fortunate for me that I came upon Onchi and Hiratsuka and Azechi—to name only three—when I did. I cannot specify exactly what they meant to me, what significance they held and still hold, but I suppose their impact derived from three factors. First, they refreshed my education in design, and anyone who wants to work in any of the arts had better know all about that fundamental component that he can master, for the design of a good print poses exactly the same problem as the design of a good string quartet or a decent novel. Second, these artists taught me how exciting it is to experiment in new fields and to exercise the mind to its fullest. Third, they showed me better than I had seen before or have seen since what dedication to art means.

Before these men I am contrite. A life in art for them has been so unjustly difficult, and for me so unexpectedly easy, that a moral chasm exists between us that only contrition can bridge. I suppose that if I had been born a Japanese with an artistic drive toward the creation of excellent form and color I might have had the courage these men have had. But I cannot be sure. Therefore, since they have played so important a role in my education, I have come to think of them with envy and admiration.

This book is an attempt to express that admiration.

In the commentaries that follow, the technical information given on the page facing each print has been based on data supplied by the artists themselves. My own remarks, as will be seen, are more subjective in nature. The contest in which these ten prints were chosen is described in the concluding section of this book.