Читать книгу The Last Sheriff in Texas - James P. McCollom - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Keep Austin Weird” T-shirts wouldn’t appear for another half century, but the capital was already well distanced from Old Texas by the 1940s. Austin was a two-hour drive from Beeville, but it was so much farther away.

The Texas soul was split between its two great institutions of higher learning. The University of Texas at Austin embraced the values of urban Texas—expansion, outreach, the future. Texas A&M College was the corps: honor, agrarianism, tradition. The University offered liberal arts, philosophy, the school of law—the broad understanding of the universe. A&M was devoted to engineering, geology, agriculture—learning how things worked, building things, making them better. The University of Texas aspired to be the finest institution in America, the Harvard of the west. Texas Aggies cared nothing for Harvard. They aimed to be the finest institution in Texas, which meant you were the best anywhere. The University was a fraternity and sorority school of eleven thousand men and women at the undergraduate level alone; it was set in the beauty of the hills of Central Texas. A&M was a military school of seven thousand males laid out on the stark lands of the Brazos River bottom. Austin was Athens. College Station was Sparta. The Aggies mocked the fraternity boys in Austin, where the only cowboys were the “Cowboys,” just another exclusive frat rat club, safely distanced from the working cowboy by fortunate birth. Texas students told jokes that made the Aggies into clodhoppers, coarse and obtuse.

In an earlier decade, Johnny Barnhart would have gone to Texas A&M. Joe Barnhart, Johnny’s great grandfather, had left the Pennsylvania Dutch country to join the Texas Army in 1836, the year of Goliad, the Alamo, and San Jacinto. When Texas won its independence, the army settled north of Austin, near Round Rock, where he and his family farmed and ranched for fifty years. Johnny’s grandfather, another Joe Barnhart, sold out in the 1890s and bought a bigger spread near Childress, in the Texas panhandle. Johnny had heard his grandfather tell about seeing the bullet-ridden body of the outlaw Sam Bass at the blacksmith’s shop in Round Rock in 1878. Johnny’s father, the third Joe Barnhart, was a trick-riding cowboy good enough to be a U.S. Cavalry riding instructor at the start of World War I. Joe Barnhart had left ranching long ago to establish an insurance and real estate business. His older son, Joe IV, studied medicine. Johnny was in law school. Most sons of turn-of-the-century ranchers had moved on. In 1900, four of five Texans were rural. By the end of World War II, rural Texans would be less than half the population. By 1950, more than 60 percent of Texans would be classified as city folks. In downtown Beeville, Joe Barnhart and his friends wore business suits and fedoras, even in summer.

Each year on Thanksgiving Day, the mutual denigration between the Aggies and the Longhorns was celebrated on the football field. For the Longhorns, the game was a reason for the last big party of the season. For the Aggies, it was the defense of Texas tradition. Dead serious, jaws set, the Aggie band took the field in military uniforms, horns and drums resounding with

GOOD-BYE to Texas University, Farewell to the orange and the white,

Here’s to the good old Texas Aggies, they are the ones who show

the fight! fight! fight!

The Texas Aggies, like everyone else playing against time, rarely won the Thanksgiving Day game. They lost again that year that Johnny led the yells: 6–0.

Johnny’s year as head pep leader saw UT’s first female cheerleader. Patsy Goff was so good at tumbling that the student body revolted against the no-females policy mandated by the band director, Colonel Hurt. (The colonel, a displaced Englishman, feared the sight of bare female legs would distract the public from the band’s on-field performance.) The others on the pep squad were a Texas boy named Coy Foster, and two beach boys from California, in Texas for the wartime V-12 program.

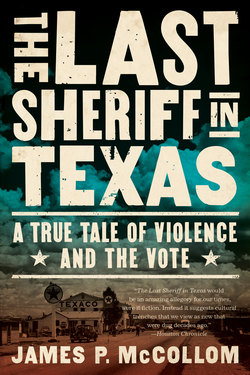

California! Johnny loved to hear them talk about the West Coast. Together, they worked several California cheers into the Longhorn list. California was just another ingredient in the vast new world of knowledge and experience that was the university. But to his surprise, Johnny found that for the California boys, none of the world’s great issues were as interesting as Texas. They were fascinated, enthralled with Texas. They wanted boots. They wanted rodeos, horses, range. Barbecues. Deer hunts. They wanted to know all about those things that people opening Time magazine in November 1947 had read under the headline Texas, where a tattooed thug had pumped a sheriff full of lead, had bloodied his white shirt, but did not cause his white hat to fall from his head. The California boys wanted to know about the real Texas. They wanted to know about Vail Ennis.