Читать книгу San Francisco's Lost Landmarks - James R. Smith - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

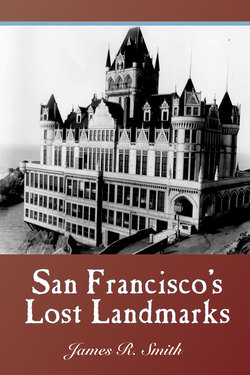

ОглавлениеCliff House number three—Sutro’s French Chalet Cliff House. The rowdy party days were over. Sutro brought civility to Ocean Beach. —Author’s collection

Chapter 3

Ocean, Bay & Wharf-side Attractions

MEIGG’S WHARF AND THE COBWEB PALACE

San Francisco in the mid-nineteenth century demanded entertainment. Pockets jingled with gold. The mines, the burgeoning shipping business, the merchant trade and wild speculation fueled a runaway economy. Keyed to a fever pitch, the city wanted to play, to blow off steam. San Franciscans were soon to show the world that they were not only getting rich but knew how to spend their new wealth as well.

Harry Meigg recognized his new wharf on Francisco near Powell Street as an ideal place for the merchant and tourist trade. Always looking for that extra buck, Harry encouraged his old friend Abe Warner, among others, to open a business on Meigg’s Wharf. In the city’s early days, North Beach began its metamorphosis into the place to be.

Abe opened the Cobweb Palace at the foot of Meigg’s Wharf on the north side of Francisco in 1856. His establishment earned its name by the strings of cobwebs hanging from the rafters. Abe admired both spiders and their webs. He refused to sweep them down and chastised anyone who did. “Filibuster” Walker once poked at a web with his cane. Known in the city as much by his floppy slouch hat and long black cape as by his dissertations, William Walker claimed a reputation as a famed Central American orator. “That cobweb will be growing long after you’ve been cut down from the gibbet,” Abe remarked. A Honduran firing squad executed Walker about three years later.

Today, Fisherman’s Wharf only hints at what Meigg’s Wharf must have been like. The clean smell of the bay intermingled with steamed crabs and shellfish, fresh baked bread, and spices hauled off ships from the Orient. Waves slapped the pilings, stevedores shouted out the contents unloaded from of the ships, and drayers called to their mules as they cracked their whips and rumbled heavy-laden carts off the dock’s. Organ grinders, screaming children, and seagulls added to the wild cacophony of noise intermittently punctuated by gunshots.

Crowds gathered at Abe’s tavern to view his extensive collection of oddities. The Cobweb Palace displayed scrimshaw of sperm whale teeth and walrus tusks. Totem poles from Alaska adorned the entryway. Wonders from the Orient included Japanese No theater masks. War clubs and the like from the South Pacific and taxidermy of all sorts joined the collection. Abe’s live menagerie included trained parrots, monkeys, and various small animals, as well as the occasional bear and kangaroo. One parrot named Warner Grandfather often spouted, “I’ll have a rum and gum. What’ll you have?” He swore in four languages and enjoyed the freedom of the saloon. An old, crippled sailor sat outside Abe’s bar selling peanuts to young couples and children. Meant for tourists, the peanuts often found their way from little hands into the mouths of the parrots and monkeys. All manner of food and leftovers fed the bears. Abe spent almost nothing feeding his animals.

A day of excitement begged a visit to Meigg’s Wharf. More than just a hangout for sailors and sea captains, Meigg’s Wharf and the Cobweb Palace exuded a carnival atmosphere. On any Sunday, young couples and families strolled on the wharf, taking in the sights, visiting the shops, testing their skill at the shooting gallery, and sampling Abe’s free crab chowder. The Palace offered a new experience for the locals and tourists—pier-side dining. The Dungeness crabs were sweet, succulent, and sure to please. Customers dined on simple fare of cracked crab, clam chowder, mussels, and an excellent local French bread.

Abe had a fancy for tawdry paintings of nudes, reputedly collecting over a thousand. Dust and cobwebs obscured most of those hung on the walls. However, Abe was a tidy man, well groomed and of good reputation, the cleanliness of his bar notwithstanding. He held court over all from his usual position behind the bar. Though the drink of choice at Abe’s was a hot toddy made of whisky and gin boiled with cloves, he also served the finest liquors and brandies from France.

The ships at Meigg’s Wharf disgorged everything a growing new city needed. Ready-built mansions with numbered pieces came from New England round the Horn. Fresh fruit and vegetables were shipped in from Mexico and Chile. California couldn’t feed itself yet, let alone a nation. Spices, chinaware, and fine cloth arrived from the Orient. The local fishing fleet offloaded their abundant daily catch. Lumber ships carrying virgin heart redwood arrived from Northern California towns like Scotia and Eureka. And, the goods San Francisco needed often came via Meigg’s Wharf.

Abe with a few of his friends and customers, in front of the Cobweb Palace shortly before it was demolished. That location today can be found at 444 Francisco Street, nearly five blocks from the Bay where Powell meets Jefferson and the Embarcadero. The City constructed a breakwater enclosing Meiggs Wharf then filled in the cove it created. See page 13. —Courtesy of The Bancroft Library,University of California, Berkeley

Pen-and-ink drawing of the interior of Abe Warner’s Cobweb Palace. Parrot Warner Grandfather swings amid the webs that could grow as long as six feet. —Author’s collection

Businesses spawned around the wharf taking advantage of the short hauling distances from the ships. Sardine canneries built up just west of the wharf. The bay teemed with sardine and they provided fine protein for hungry miners. Sawmills opened, taking the raw logs to produce not only lumber, but also the fine wooden trim and scrollwork required for an ever more opulent city. Factories, such as Ghirardelli Chocolate, added to the city’s flavor. Each ethnic group brought its skills, traditions, and trades, making them wholly San Francisco’s.

Meigg’s Wharf, built in the mid-850s by Harry Meigg. —Author’s collection

Abe Warner retired in 1897 at the age of eighty. By then, the state of Meigg’s Wharf reflected a serious decline in business. The shipping trade returned to the piers by the new Ferry Building, where the wide Embarcadero Road and new rail lines could quickly dispatch goods. Fancier attractions elsewhere beckoned the crowds. Nickel trolleys bused folks to Sutro’s Baths at Ocean Beach where a dime gained entry with fifteen cents more to swim indoors. The Baths boasted the world’s largest indoor saltwater pool, which held over a million and a half gallons. The structure also housed a mechanical arcade, a theater with ongoing stage productions, three restaurants, and a museum, all under a magnificent Victorian glass-paned roof covering two acres. Awe-inspiring Golden Gate Park with its paved carriage roads and glorious exhibits drew both the elite and the masses. Stunning views of the Pacific and Seal Rock from the French chateau-inspired Cliff House attracted locals and tourists alike. San Francisco now sported a taste for the fine life and the dingy sights around the old wharf simply would not do.

COBWEB PALACE

Michael Doyle wrote a letter to his grandchildren in the 1920s telling about his childhood and early years in San Francisco. In that letter he related the following:

Northerly, I looked down upon the peninsula’s head with its two blunt horns, Russian and Telegraph hills, quite bare in those days, between which protruded Meigg’s Wharf like a long tongue lapping the waters beyond….