Читать книгу Instrumental - James Rhodes - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

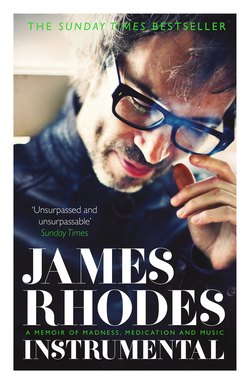

ОглавлениеTRACK FOUR

Bach-Busoni, Chaconne

James Rhodes, Piano

(shut up, I’m proud of this one)

Bach wrote several groups of pieces in sixes – six partitas for keyboard, six for violin, six cello suites, six Brandenburg Concertos and many more. Musicians are weird like that.

There was a piece of music that Bach wrote around 1720 which was described by Yehudi Menuhin as ‘the greatest structure for solo violin that exists’. I’d go much further than that. If Goethe was right and architecture is frozen music (what a quote!), this piece is a magical combination of the Taj Mahal, the Louvre and St Paul’s Cathedral. It is the final and longest movement of his second (of six, of course) partita for violin. It is a set of variations (sixty-four of them, I counted) on a theme that drags us through every emotion known to man and a few bonus ones too. In this case, the subject is love with her attendant madness, majesty and mania.

Brahms said it best in a letter to Schumann’s wife: ‘On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind.’

THE SEXUAL ABUSE WENT ON for nearly five years. By the time I left that school aged ten I’d been transformed into James 2.0. The automaton version. Able to act the part, fake feelings of empathy, and respond to questions with the appropriate answers (for the most part). But I felt nothing, had no concept of the expectancy of good (my favourite definition of ‘joy’), had been factory reset to a bunch of fucked settings, and was a proper little mini-psychopath.

But something happened to me bang in the middle of all of it that I am convinced saved my life. It remains with me to this day and it will continue to do so as long as I’m alive.

There are only two things I know of which are guaranteed in my life – the love I have for my son, and the love I have for music. And – cue X Factor sob-story violins – music is what happened to me when I was seven.

Specifically classical music.

More specifically, Johann Sebastian Bach.

And if you want to be ultra detailed, his Chaconne for solo violin.

In D minor.

BWV1004.

The piano version transcribed by Busoni. Ferruccio Dante Benvenuto Michelangelo Busoni.

I can keep going with this for a while yet. Dates, recording versions, length in minutes and seconds, CD covers etc etc. No wonder classical is so fucked. A single piece of music has dozens of extra little pieces of information attached to it, none of which is important to anyone other than me and the other four piano-mentalists reading this.

The point is this: in anyone’s life, there are a small number of Princess Diana moments. Things that happen that are never forgotten and have a significant impact on one’s life. For some it’s the first time they have sex (aged eighteen for my first time with a woman, a hooker called Sandy, who was Australian and kind and let me watch porn while we did it in a basement flat near Baker Street for £40). For others it’s when a parent dies, a new job starts, the birth of a child.

For me there have been four so far. In reverse chronological order, meeting Hattie, the birth of my son, the Bach-Busoni Chaconne, getting raped for the first time. Three of these were awesome. And by the law of averages, three out of four ain’t bad.

I’ll take it.

A few things about Bach that need clearing up.

If anyone does ever think about Bach (and why would they?), the chances are they will see in their heads an oldish guy, chubby, dour, bewigged, stern, Lutheran, dry, unromantic and in dire need of getting laid. His music is considered by some to be antiquated, irrelevant, boring, shallow and, like the beautiful architecture in Place des Vosges or Regent’s Park, belonging to other people. He should be confined forever to cigar adverts, dentists’ waiting rooms and octogenarian audiences at the Wigmore Hall.

Bach’s story is remarkable.

By the age of four, his closest siblings have died. At nine his mother dies, at ten his father dies and he is orphaned. Shipped off to live with an elder brother who can’t stand him, he is treated like shit and not allowed to focus on the music he loves. He is chronically abused at school to the point that he is absent for over half of his school days to avoid the ritual beatings and worse. He walks several hundred miles as a teenager so he can study at the best music school he knows of. He falls in love, marries, has twenty children. Eleven of those children die in infancy or childbirth. His wife dies. He is surrounded, engulfed by death.

At the same time that everyone he knows is dying, he is composing for the Church and the Court, teaching the organ, conducting the choir, composing for himself, teaching composition, playing the organ, taking Church services, teaching harpsichord, and generally going mental in the work arena. He writes over 3,000 pieces of music (many, many more have been lost), most of which are still, 300 years later, being performed, listened to, venerated all around the world. He does not have twelve-step groups, shrinks or anti-depressants. He does not piss and moan and watch daytime TV drinking Special Brew.

He gets on with it and lives as well and as creatively as he can. Not for the fanfare and reward, but, in his words, for the glory of God.

This is the man we are dealing with here. Drenched in grief, emerging from a childhood of disease, poverty, abuse and death, a hard-drinking, brawling, groupie-shagging, workaholic family man who still found time to be kind to his students, pay the bills and leave a legacy totally beyond the comprehension of most humans. Beethoven said that Bach was the immortal God of harmony. Even Nina Simone acknowledged that it was Bach who made her dedicate her life to music. Didn’t help her so much with the heroin and alcohol addiction, but hey ho.

Clearly he was not going to be emotionally normal. He was obsessed with numbers and maths in a scarily OCD way. He used the alphabet as a basic code, where each letter corresponds to a number (A B C = 1 2 3 etc). BACH. B=2, A=1, C=3, H=8. Add them up and we get 14. Reverse that and we get 41. And 14 and 41 appear all the time in his works – number of bars, number of notes in a phrase, a hidden musical signature placed at key points in his works. It probably kept him safe in that weird way all those afflicted with light-flicking, counting and tapping tics feel safe. When it’s done right.

Aged twelve he would sneak downstairs when everyone was asleep, steal a manuscript that his dickhead brother wouldn’t let him look at, copy it out and hide it before carefully placing the original back where it belonged and going to bed for few hours’ sleep before rising at 6 a.m. for school. He did this for six months until he had the entire musical score that he could study, pore over, inhabit.

He loved harmony so much that when he ran out of fingers he would put a stick in his mouth to push down additional notes on the keyboard so he could get his high.

You get the idea.

Back to the Chaconne. When his first wife, the great love of his life dies, he writes a piece of music in her memory. It is for solo violin, one of the six (of course) partitas he composed for that instrument. But it isn’t really just a piece of music. It is a musical fucking cathedral built in her memory. It is the Eiffel Tower of love songs. And the crowning achievement in this partita is its last movement, the Chaconne. Fifteen minutes of shattering intensity in the heartbreaking key of D minor.

Imagine everything you would ever want to say to someone you loved if you knew they were going to die, even the things that you couldn’t put into words. Imagine distilling all of those words, feelings, emotions into the four strings of a violin and concentrating it into fifteen taut minutes. Imagine somehow finding a way to construct the entire universe of love and grief that we exist in, putting it in musical form, writing it down on paper and giving it to the world. That’s what he did, a thousand times over, and every day that alone is enough to convince me that there is something bigger and better than my demons that exists in the world.

Enough hippie.

So in my childhood home I find a cassette tape. And on the tape is a live recording of this piece. Live recordings are, always, unequivocally better than studio ones. They have an electricity about them, a sense of danger and the thrill of a moment in time captured forever just for you, the listener. And of course the applause at the end gives me a little bit of wood because I dig things like that. Approval, reward, praise, ego.

I listen to the tape on my battered old Sony machine (with auto-reverse – you remember the almost magical joy of that?). And, in an instant, I’m gone again. This time not flying up to the ceiling and away from the physical pain of what’s happening to me, rather I’ve gone further inside myself. It felt like being freezing cold and climbing into an ultra-warm and hypnotically comfortable duvet with one of those £3,000 NASA-designed mattresses underneath me. I had never, ever experienced anything like it before.

It’s a dark piece; certainly the opening is grim. A kind of funereal chorale, filled with solemnity, grief and resigned hurt. Variation by variation it builds and recedes, expands and shrinks back in on itself like a musical black hole and equally baffling to the human mind. Some of the variations are in the major key, some in the minor. Some are bold and aggressive, some resigned and weary. They are by turns heroic, desperate, joyful, victorious, defeated. It makes time stand still, speed up, go backwards. I didn’t know what the fuck was happening, but I literally could not move. It was like being on the receiving end of a Derren Brown trance-inducing finger-click while on Ketamine. It reached something in me. It reminds me now of that line in Lolita where she tells Humbert that he tore something inside her; I had something ripped apart inside me but this mended it. Effortlessly and instantly. And I knew, the same way I knew the instant I held him in my arms that I’d walk under a bus for my son, that this was what my life was going to consist of. Music and more music. It was to be a life devoted to music and the piano. Unquestioningly, happily, with the doubtful luxury of choice removed.

And I know how clichéd it is, but that piece became my safe place. Any time I felt anxious (any time I was awake) it was going round in my head. Its rhythms were being tapped out, its voices played again and again, altered, explored, experimented with. I dove inside it as if it were some kind of musical maze and wandered around happily lost. It set me up for life; without it I would have died years ago, I’ve no doubt. But with it, and with all the other music that it led me to discover, it acted like a force field that only the most toxic and brutal pain could penetrate.

Imagine what an aid that is.

By this time I had managed to find an exit strategy from the school of rape and applied to some provincial fuck-bucket of a school in the country. But I had now become a kind of classical music superhero – off I went to boarding school aged ten, piano music as my invisibility/invincibility cloak.

It was a bit of out of the frying pan and into the industrial meat grinder, because I was by now a very odd kid, all tics and bed-wetting and spaced out and just weird. I threw up continuously on the way there, was so terrified I didn’t speak to anyone for the first few days, was wandering round shell-shocked like some bomb survivor with his hearing broken and his brain still reverberating.

I was also the only Jew at this school. They literally had never even seen one before. I was like a science experiment – kids actually touching and prodding me to see if I ‘felt different’. And they only knew I was Jewish because the cunt of a headmaster announced to the entire school at assembly one morning that I’d be absent for a day as I was celebrating the Jewish New Year. Which fell about a month into my first term.

But it didn’t matter. Really it didn’t. Because in comparison to what else was going on this was nothing. Regular beatings, blowing older boys (and staff) for Mars bars (I was more innocent back then – money meant nothing, sugar everything), torturing animals (newts, flies, nothing bigger that I can recall should that ease the disgust of the animal lovers amongst you), hiding, spending countless hours in locked toilet cubicles either bleeding and shitting or fucking and sucking. Throwing myself at older men and boys and doing anything they asked of me because, well, that was what you did. In the same way as shaking people’s hands meant hello, offering yourself to some perverted bastard because you recognise ‘that’ look (paedophiles – don’t think for a minute you’re anonymous to those who’ve been through it) was absolutely normal and expected. Like being on holiday aged ten and going off with a dude in his forties (there with his family) into the toilets to blow him for an ice cream and still not classing it as abuse even today because I chose it. I gave him the nod. I led the way. I wanted an ice cream.

But I had music now. And so it didn’t matter. Because I finally had definitive proof that all was well. That something existed in this horrific fucking world that was just for me, did not need to be shared or explained away, that was all mine. Nothing else was, except this.

The school had a couple of practice rooms with old, battered upright pianos in them. They were my salvation. Every spare moment I got I was in them, noodling away, trying to piece sounds together that meant something. I would get to breakfast as early as possible, before anyone else, because by this stage any kind of social interaction was too startling and fraught with danger, choke down Rice Krispies covered in white sugar, sit on my own and avoid any and all contact, then leg it for the piano.

I was shit, too. Not that it matters, but really, I was truly dreadful. Look at any one of a thousand Asian toddlers whacking out Beethoven on YouTube for the real thing, then imagine them with three stubby fingers and the brain of an Alzheimer’s-addled stroke victim and you’re approaching my level of skill. I laugh so hard now when parents push their kids up to me at CD signings post-concert and instruct me to tell them how long little Tom needs to practise for each day so that he can pass his grades and be proficient. My response is usually ‘As long as he wants to. If he’s not smiling and enjoying it then don’t worry. If he’s got the piano bug it doesn’t matter – he’ll find a way to make it.’

I found a way. I learned how to read music – it isn’t hard and it’s an essential first step. But of course I had no idea about things like fingering or how exactly to practise. Which finger to use on which note is, arguably, the most important part of how to learn a piece. Get it right and it makes your job so much easier. Get it wrong and it’s an uphill battle that will never be fully secure in performance. There are so many factors to take into account. Here’s an easy one, for example: what combination of fingers will make the melody sound clearest, smoothest, joined up and voiced as the composer intended, while still playing all the other notes and chords that are surrounding it? Some fingers are weaker or stronger than others and shouldn’t be used in certain places; the thumb, for example, is heaviest and will make whichever note it hits sound louder than, say, the fourth finger, and so that has to be considered. The physical link between the fourth and fifth fingers is comparatively quite weak (especially in the left hand) and so when playing passages containing scales you should try and move from the third finger to the little finger, missing out the fourth entirely, in order to make them more even. Trilling (an ultra-rapid alternation of two notes, usually side by side, to create a vibrato, quivering sound) is easiest between the second and third fingers, but sometimes the same hand is playing a chord at the same time and so you need to trill between the fourth and fifth fingers to make everything flow naturally.

Sadly, the easiest combination to use physically doesn’t always work musically (it can make things sound choppy or disconnected, uneven or unbalanced). Where a physical connection between two notes is impossible (too big a jump or simply not enough fingers) you need to learn to use weight to make the join sound totally connected, even if you’re not actually physically connecting them. There must always be awareness not just of the note that you are playing but the relation of that note to what has come before and what is coming afterwards, and using the correct fingering is the surest way of doing that.

Sometimes you can play some of what the right hand is meant to be playing with the left hand to make it easier and vice versa, even if it’s just one note of a chord – but it doesn’t usually say that in the score and so you need to learn to spot opportunities to do it, mark it in the score, remember it, finger it, ensure the melodic line is still clear, that you’re not using the pedals (which sustain and/or dampen the notes) too much, that you are in fact playing all the notes the composer wrote down, that the runs are even and balanced, the chords are correctly weighted (each individual finger must use a slightly different weight and force when playing a chord with five notes simultaneously), that the speed and volume are perfectly judged, graded and executed, the tone (how to use the weight of the hand, arms, fingers to make the chord you’re playing sound a certain way) isn’t too harsh or too soft, the wrists and arms aren’t too tight, your breathing is right, the volume is measured and correct, and so on. It’s like a giant maths puzzle where you get to use logic to solve it. But if you don’t understand logic in the first place you’re shooting in the dark.

The school I was at had a piano teacher of sorts, and he and I had a few sporadic lessons together, but he had no clue either. Of course he didn’t – he was the music teacher who did everything and happened to play the piano at a pretty low level, and so he was the ‘piano teacher’ there. He knew as much about fingering, tone, breathing or posture as I did.

And all of this stuff is purely mechanics. The physical ‘how to’ of learning and playing a piece. It doesn’t even touch on musical interpretation or how to memorise a piece. Christ, sometimes Bach didn’t even specify what instrument a piece should be played on, let alone things like the speed and volume of it. Things got more detailed with Mozart and Beethoven as composers started to indicate those things, but even so they are merely signposts. There will never, can never, be two identical performances of the same piece of music, even when you’re playing it twice yourself. There is an infinite choice of interpretation, and everyone has different opinions as to what is the ‘right way’, what is respectful/disrespectful of the composer, what is valid, what is exciting, what is dull, what is profound. It’s entirely subjective.

And where to even begin with memorising approximately 100,000 individual notes so that even when phones go off, latecomers shuffle in, the wrong finger is accidentally used thus fucking up muscle memory completely, you are still totally secure. Some people visualise the score in their head, complete with coffee stains and pencil markings. Some rely on muscle memory. Some even use the score (which goes very much against the norm in solo recitals but is never a bad thing if it enables a great performance and removes crippling nerves). For me the best way is to play a piece through at a tenth of the normal speed without music because if you can get through it like that then there is nothing to worry about. Imagine an actor rehearsing a giant, hour-long monologue, going through it and pausing for three seconds between each word – if he can do that he knows it inside out and will nail it during performance. Playing it through in my mind, without moving my fingers, away from the piano and in a darkened room is a great memorising tool as well. Seeing the keyboard and my fingers on the right notes in my mind’s eye proves invaluable.

And so learning the piano is maddening because it is at once an exact and an inexact science; there is a specific and valid way to master the mechanics underlying the physical performance of it (even this is dependent on physical attributes such as size, strength, finger span etc), and an inexact, ethereal, intangible route to find the meaning and interpretation of the piece being learned. And figuring out all of this as a vaguely retarded ten-year-old, pretty much entirely on his own and emotionally and physically fucked, was a bit of an ask.

I remember the first time I learned a full piece – the sense of achievement and total, utter delight I felt. It doesn’t matter that it was Richard Clayderman’s ‘Ballade pour Adeline’ (well to be fair it kind of does, I can only apologise) or that it was probably riddled with wrong notes. I had learned something, from memory, and could play it the whole way through. And all the arpeggios sounded fast and impressive and just like the guys on my tapes sounded, and holy shit this is the best thing that’s ever happened to me. Christ how I wanted to play it to people, but there was no one there to get it, to hear it, to understand what it meant. I had to keep it just for me even if my heart was exploding with excitement, and that somehow made it even more special.

I was such a well-adjusted kid.

The only thing that came close to my worship of all things piano was smoking. Fucking smoking. The best invention since anything anywhere. This whole book could be a love letter to tobacco. The only thing greater than being on my own as a kid and playing the piano was wandering around hiding from the world smoking cigarettes. These magical cylinders with the most extraordinary medicinal qualities offered me everything I felt was missing. Getting hold of them was easier than you’d think, especially in 1985 – friendly newsagents, older kids, the odd kind (and horny) teacher. Silk Cut was my best friend.

I look at my life today and realise not much has really changed – Marlboro now, but cigarettes and the piano are the central things in my life. The only things that will not, cannot, let me down. Even the threat of cancer would simply be an excuse to finally watch Breaking Bad in its entirety and take a metric fuck-tonne of drugs.

The thing about smoking that they don’t tell you is how good it is at stifling feelings. Later I found out that in several of the psych wards I was in, they actively encouraged patients to smoke as it made the nurses’ job a lot easier. There is nothing as terrifying to a mentally ill person as a feeling. Good or bad doesn’t matter. It still has the potential to turn our minds upside down and back to front without offering the vaguest clue how to deal with it reasonably or rationally. I am at least forty-three times more likely to top myself if I am not smoking. And so I smoke. Whenever I can, as much as I can. The odd occasion I’ve tried to stop has always been to please other people – the girl, family, society. Never works. I am a master at engineering a crisis that allows those close to me to grant smoking consent again. If there’s a loaded gun (real or imagined) or a pack of cigarettes in front of you, take the smokes every time. I know that’s off-message. But good God they work wonders for me. Even the thought of being able to smoke at a certain future event, be it a concert, party, interview, restaurant, keeps me on a somewhat even keel. Take that away (airports, for example) and I’m going to fuck your shit up. It’s why I more often than not come back out through security for a last smoke and then all the way back through it again before flying off anywhere. Totally worth getting molested by the TSA assholes yet again. I’m not proud of it. I know it makes me seem like a wanker. A slave. A raging addict in total denial. I don’t even care. I am all of those things and I will always be pathetically grateful for Big Tobacco.

So in a way, there were, on a good day, sufficient positive things to counteract the negative and I was happy enough at boarding school. I got into this cycle of terror (bullying, aggressive and unwanted sex, bewilderment) followed by the calm of space to smoke, play piano, listen to music. It reminds me of what it must be like for a soldier to come back from action to his home country for a few days before shipping off again. And this cycle continues unabated today. Terror of being on stage, of being intimate with Hattie, of seeing the psychiatrist, of being with my son and its attendant feelings, of being in social situations, circumstances I cannot control. And relief when home with a piano, locked door, ashtray, US TV shows, alone, uninterrupted. Time alone. The Holy Grail.