Читать книгу I Still Dream - James Smythe, James Smythe - Страница 8

MONDAY

ОглавлениеI’m sifting through the post, looking for the telltale return address on the telephone bill that I’m going to steal before my parents can see it. My glasses steam up, because Mum keeps the house warm all the time, and my glasses always steam up when it’s raining outside, putting me in a foggy microclimate of my very own. I try to clean them on my shirt, but that’s damp as well. I end up smearing the water around. Hate that. But then, here we go, some industrial estate in Durham. This is it. The phone company has started sending the letters unmarked, which I suppose prevents fraud or something, but really just makes my life a lot harder. The rain kicks up, sounding like a snare drum; the rat-a-tat-tat of the start of a song. I kick my shoes off, slide them under the radiator. I don’t want wet footprints through the house. One less thing for Mum to freak out about. As I get upstairs, I yank off my drenched tights, chuck them into the basket in the bathroom. Grab socks from the airing cupboard, still warm, and I go to my room, lie on the bed, pull them on with my feet stuck up in the air. The bill next to me on the bed. My bed, like the rest of my room, is a mess. That’s what Mum says, but I know that everything has its own place. Maybe it’s just not as ordered as her stuff is, but then I’ve never been one for that level of organisation.

Stub comes up, chunk of tail trying to swish and failing. He noses at me.

‘Not now,’ I say, which I reckon might be all I ever really say to the cat. But, really, not now. There’s a bit of time pressure here. Every month I intercept the bill as soon as it arrives. I panic, because I know how bad it’s going to be. I need them to not see it; and I have to read the number myself, to know how bad it’s going to be. I use this old letter opener that used to be my dad’s – my real dad’s, but maybe it was his dad’s first, I don’t actually know – and I slide it along the stuck-down flap. Every time, I try to prise the glue apart rather than cutting it. Every time, I tell myself that, if I manage to do this successfully, stealthily, I can put the letter back afterwards, and they’ll never know. But I always wreck the paper so much it’s not even a remote possibility. It’s a ritual now. Every month I read the whole bill. I recognise the calls I’ve made, the times that I made them. Every weeknight of my life I get home from school, and then, like, an hour later I’m on the phone to the people that I’ve just spent the entire day with, talking about the things we did – and did together! – earlier that day. I know it’s stupid, I know, but it’s what we do. Everybody does it. We take it in turns with who calls who, because otherwise you get an engaged tone for hours. And, God, if you get one of them when you know you’re meant to be speaking to somebody else, that’s the most tense hour or whatever of your life. Because, who are they talking to? And what does that mean?

Then, when I’ve read the bill, I get rid of it. Throw it in a bin on my way to school. I know that doesn’t solve anything. It doesn’t stop the money going out of their account at the end of the month, and it doesn’t stop them asking where the bill is, raging at the amount, shouting at me. They know I’ve taken it, but I’m strong. I blame the postman. Paul keeps threatening to make me pay some of it back out of my Saturday wages or whatever, though I’m meant to be saving for university, so I don’t think he’s serious. I want to tell them: it’s not because I don’t want them to see it, I just have to know how bad it’s going to be. Every month they tell me that I’ve got to think about other people with the phone, that somebody might be trying to get through. And, as well as thinking about other people, I should think about myself. That’s my mum’s favourite one. Think about yourself, Laura, she says; because you have to work hard this year to make sure that everything else falls into place. Every month we have the conversation, and I’m like, I know, Mum. I swear, I know. Doesn’t mean I can’t speak to my friends.

And it doesn’t mean I don’t want to use the Internet, either. And it’s that 0845 AOL number that’s been the real cost these past few months.

This month? The total at the bottom of the bill is huge. Biggest it’s been. My hands shake. Shit.

I hear a bang from downstairs. The front door, the slamming shut of it.

‘Laura?’ my mother calls. Does she sound angry? I can’t tell. The sound of her feet on the landing, coming up the stairs. Walking so heavily that I’m sure it’s because she wants me to hear her. I open the second drawer down and throw the envelope in, all the different bits of it. Pages and pages of numbers, like some awful spreadsheet – and when has a spreadsheet ever not been bad news? – but the drawer jams, slightly, when I try to shut it, because it’s so crammed full, so I have to really work it to get it closed, creeping my hand in, forcing the pages along, pushing them down. ‘Are you home?’ she shouts, from right outside my bedroom.

‘Yeah, come in,’ I say. Hand shakes; voice shakes. Come on, Laura, keep it together. ‘You’re home early,’ I say, as she pushes the door open. Before she can speak.

‘You’re soaking wet,’ she says. I can see myself in the mirror, over her shoulder. My hair’s a state. She really hates that I don’t do more with my hair. ‘Didn’t you have your little brolly with you?’

‘It’s fine,’ I tell her. She looks past me: at what I see as order, but she sees as something entirely chaotic.

‘And you keep this room so cold,’ she says, looking at my open window; an open window that she basically forces me to have because of her insane addiction to constantly-on radiators. ‘You’ll catch your death,’ but that bit of caring is only a pretence; a prelude to what she really wants to say. ‘You have to sort this heap out, you know.’ She scans the whole room, looking at every single bit of it, somehow, in only a few seconds. Like her eyes are able to flick from mess to mess faster than any other human’s can. Somehow inhuman.

‘Fine,’ I reply. The desk is covered in electric leads and books and bits of schoolwork; and there are piles of clothes on the floor; and there’s all this stuff Blu-tacked to the walls, which they warned me against, because you’ll never get Blu-tack off, and it’s us who’ll end up having to scrape it off when you’ve gone to university, and on and on and on. They gave me the desk a couple of years back, after Paul salvaged it from his office. I got him to paint it black for me, because I was going through a phase, Mum says. I say I’m still going through it. There are bits where I’ve chipped the paint, and there’s the old cheap wood veneer poking through.

Mum glances at my drawers – the tape drawer is open, boxes crammed in, tapes threatening to unspool under the pressure – and I picture the drawer I crammed the bill into popping open, a jack-in-the-box, and the letter flying up into the air, the pages of the bill – many, many pages of itemised phone calls – showering down around us.

‘Are you all right?’ She asks this every day. I think she’s hoping that, one day, she’ll hit the jackpot, and she can say, See, I can always tell.

‘I’m fine.’ I don’t say: I really am not fine; I’ve got a phone bill in my drawer that incriminates me to the tune of nearly a hundred and fifty quid, and you’re going to go absolutely bloody mental when you find out.

‘School was all right?’

‘Same as always.’ Mum nods. She rolls her tongue around the front of her mouth, between her teeth and the inside of her lip. This is what she does when she’s thinking about something. Or, when she’s thinking of whether to say whatever it is she’s trying to stop herself from saying. Weighing up whether the potential argument’s worth it or not.

Today, it’s not. ‘Okay,’ she says instead, and she backs away. I wait for her to say something else, but she doesn’t. Not a word, just this weird hum of some song I only slightly recognise; and then the click of the television they have at the end of their bed coming on, the theme tune to Neighbours.

I time the slam of my door to the end of the song.

I can’t deal with the BT bill yet, in case she comes back. She’s got a habit of doing that. Knowing when something’s up, and surprising me a few seconds later, like she’s trying to catch me in the act. I take my clothes off, put them on the radiator. Pull joggers on, a Bluetones T-shirt I wouldn’t really wear out of the house any more. I turn on my computer, and I think about going online, dialling into AOL and getting on with more of my Organon project. But I can hear Mum muttering something, and I can hear Madge and Harold talking on the telly, and I know I wouldn’t get away with it, not right now. Fingers on the home keys, waiting for something. Not yet.

After dinner – leftovers, because it’s Monday, and every Monday is leftovers – Paul tells me to wait a minute, to stay where I am. Not in a nasty way. He couldn’t do anything in a nasty way, because he’s Paul. He’s just Paul. Anyway, he says, ‘We have to have a talk about this.’ And he pulls out a BT bill. Not the one from my drawer; this one, the envelope’s been destroyed. A ravenous animal tearing at a carcass. He slides it onto the table in front of me. It’s addressed to him at work, not here.

‘What is it?’ I ask. I tell myself to stay cool. I don’t know the details. I’m ignorant. An idiot, when it comes to things like this. I absolutely definitely don’t know that awful number right there at the end of it. The last few that went missing were blamed on the postman, and Paul got angry about the amount BT charged him, so they were looking into it. He must have had a copy sent to him at work or something.

Clever old Paul.

‘This has got to stop, Laura. Your mother and I—’ Every conversation where he tells me off, he invokes my mother, because her permission gives him the right to say whatever it is he’s going to say – he’s been living with us for five years now, and he’s still not comfortable being That Guy – so he looks at her, and she nods, and then he says, ‘we really need you to curb the phone use. Ten minutes every night. Nothing more than that, okay? Because this is the most expensive bill yet, and we haven’t made these calls. We barely even use the bloody thing.’

‘It’s just too much,’ my mother says.

‘It’s not my fault,’ I reply, which feels natural enough. Denial, first; always.

‘You’re making the calls, Laura. So it kind of is your fault, actually.’ Paul doesn’t really get angry. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him even close to furious. Just this quiet steaming, where his face goes puffy and red because of what he’s choosing not to let out. ‘We’re not going to ask you to pay us back, but we have to put an end to this.’ Mum doesn’t meet my eyes this whole time. She either looks at him or down at her food, which she’s barely touched; because she never eats leftovers, which makes me wonder why the hell I have to. ‘And then there’s the Internet,’ Paul says.

‘Yes,’ I say. I don’t say: You are correct, there is the Internet, it is indeed a thing that now exists. I don’t want this conversation going apocalyptic.

‘It’s really ridiculously expensive, Laura. So, from now on you’re allowed to use it at weekends only, when it’s cheap, and even then, only for an hour.’

‘An hour?’ The room goes silent, like a TV that’s been muted, because he doesn’t get it; he doesn’t get what that is to me, not right now. He keeps talking even though I’m not hearing him. No tears, I tell myself, because it would be so stupid to cry over something like this; but I have to bite them back. Under the table, jelly legs.

‘Can I go?’ I ask, even while he’s talking, and my mother nods and does this dismissive little wave thing with her hand, not even really looking at me; and she obviously knew how this was going to go, because they’d already spoken about it. Even the way I’d leave the conversation. In advance, like: Just let her go.

I run upstairs, actually run, feet thumping into the wood underneath the carpets, and I go to my computer and I open up AOL, and I wait. I’ve wrapped the modem in a jumper already to mute the noise of it. It’s so whiny and stuttering. It sounds like hesitancy, and I always think: How come this thing that’s so amazing sounds so desperate and choked and sickly when it’s actually working?

I remember my father – my real father – bringing home a computer when I was really young. A Spectrum, with a tape deck. And you’d put the tapes in to load a game, and while they loaded, they made a noise like the modems now do, only screechier, more in pain. Oh God this hurts this hurts, and then suddenly there’s Rainbow Islands on your screen.

‘Come on, come on,’ I catch myself saying. Jittering. Like anticipation mixed with anxiety, a ball of tension in my gut and a pain in my head and every part of me slightly tingling. Every time the same, and I don’t know how bad it’s going to be until I reach the point where necessity means I’m dealing with it. I open the drawer I stuffed the bill into, take it out and put it into my rucksack, inside a geography textbook that nobody’s ever going to look inside. Then, I’ll walk through the park on the way to school, and I’ll go behind the big tree that fell over in the hurricane of ’87, and I’ll burn it. It’ll be as if it never existed.

I take out a mixtape I made for myself – or, that I made for Nadine, but hers was a copy of mine, really, because the songs degrade each time you copy them over, and I wanted the perfect version to listen to, the original, or as close to it as you can get – and I put it on. A mixtape is like a piece of art in itself. Making something where the tracks play off each other, the flow and the pace and the narrative; because they all have a narrative. While the first song is playing – You’ve got a gift, I can tell by looking; and I half-shout the words along with the song, under my breath – I pull out the box of matches that I keep at the back of my tape drawer, behind the cassettes that don’t even have boxes. Like unloved pets, waiting for new homes, for me to put Sellotape over the holes on the top of them and record over them. I pluck one of the matches out. Safety matches, the box says. Not the way I use them. I strike it, use it to light one of the joss sticks that I got from this shop in Ealing Broadway called Hippie Heaven – the smell is called Black Love, but it’s the same title as this album I love, and I don’t even know what it is, but it’s sweet and sour all at the same time – and when that’s burning, I hold the match between the fingers of my left hand and I roll my sleeve up with the right, up as far as it can go; and then I turn my arm, so that the hard bit of skin on my elbow is visible, and I carefully take the match and lay it down onto the folds and creases there. There’s a sizzle as some of the hairs, so thin and blonde I can’t even see them, burn themselves away; and then my skin, pink to black in just a moment, the bone of the match collapsing and crumbling so that you don’t know if it’s the burn or the char from the head of the wood that’s made my skin that colour.

I used to grit my teeth when I did this much more than I do now.

Afterwards, I don’t use Germolene or anything. Nadine cuts herself, I know, because she’s told me about it. She showed me her scars as if she wanted me to admire them. Hers are slick snicks along her skin, gone glossy as they’ve healed. They shine, reflect, almost. Mine – just the one, the same patch of skin – is more like a grimly depressing puddle. A scab that never quite properly heals, which passes for eczema or something if people ever notice it, and which has taken on this weird property where it almost always hurts me unless I’m actually burning it. As if that’s going to let the pain out.

‘You’ve got mail,’ my computer blurts out. Stupid tinny American accent. I was going to get some work done on Organon. Install another feature, maybe some more questions and reactions, before I go to the computer lab at school tomorrow. But the email is from Shawn. I know it’ll be a constant distraction until I’ve dealt with it.

Hey U, the subject line says. That’s how he pretty much always starts his emails. His message is nice. He writes about what he’s been up to over the last few days. This vague thing of: it’s not like we’re ever going to actually be able to meet, probably, but we’re going to make plans as if we will. Sometimes I send photographs that I’ve scanned in on Paul’s scanner. Always ones with my friends in as well, because I want to make it clear I’ve got them. There’s no way of proving otherwise.

I won’t be around for a while, I write. Parentals being assholes. I spell the word like he does, because I worry that arse just looks too strong; too defiantly British. They’re only letting me use the Internet at the weekend. Didn’t want you thinking I was ignoring you, because I’m totally not. I’ll miss you! Sometimes I write the words like they speak in Wayne’s World, because I want him to think I’m cool, and not the sort of British person that they take the piss out of in films. I read my email a hundred, two hundred times. Is it casual enough? Do I sound too eager?

Then, eventually, when I’ve worried about it so much that I’ve bitten a bit of my nail by the corner and made it bleed, I click send. A whooshing from the speakers, to indicate it’s been sent. A physical sound, the sound of travel, of movement, to reassure those people who are too used to trudging down to the Post Office. I don’t think anything’s ever whooshed with speed from the Post Office. The world’s had the Internet a couple of years now, and already it feels like sending something through the post should be dead to us.

‘You’ve got mail.’ Shawn’s replied, and it’s a bit cold, a bit quiet. Like he’s disappointed. Sure don’t worry about it, then a sad face made out of punctuation. He’s not good at punctuation in the actual message, but he uses it to make faces, that sort of thing. A man shrugging, drawn in ASCII art underscores and brackets.

I hear voices rising from downstairs. Mum and Paul, arguing about something. ‘We told her,’ Paul says. There’s such a finality to his voice. We all know full well what he’s about to do. Disconnected flashes up on the screen. I didn’t get a chance to reply before they pulled the plug, picked up the phone from downstairs and hung up the call.

I rub at my elbow, at the burn. The raw skin is so pink, and new, and sore to the touch.

There’s a knock on my door. ‘I wanted to say goodnight,’ my mother tells me, pushing open the door a little; so little that I can’t quite see her face, but I can still feel her presence through the gap.

‘Fine. Night.’ That’s it, get out now. I’m working. I’m at my desk, tinkering with Organon. I’m having to work offline, which is a pain in the backside. Organon is stubborn at the best of times, and I don’t even have my usual message boards to get any help.

‘I don’t want you to be upset with me,’ she says. I don’t say: And yet somehow you always seem to manage it. I’ve learned, over the years, to hold my tongue. The easiest way forward is to never say the first thing that comes into your head when you’re in an argument. The second thing, that’s what you should say. It never hurts as much, and it doesn’t last as long. ‘But we have to make a change. It’s a lot of money.’

‘So I’ll pay for it.’

‘What with, shirt buttons?’ Ha ha, Mum. Hilarious. ‘You’re only a year away from leaving school, Laura. You need to be thinking about the future, thinking about university. You need to save money, and so do we.’

‘Whatever,’ I reply. I try, hard as I can, to put my own definite full stop onto the word, the way that they’re both so good at doing when they want me to know there’s nothing more to say or be done.

‘Not whatever,’ she says. ‘This is serious. Important. Don’t forget to look at my computer tomorrow, please?’ and then she’s gone, the soft pad of her feet down the hallway, and the click of the light switch to let me know that her and Paul have gone to bed; that I’m expected to do the same.

Headphones out and on. Big, clunky ones that I found in a box in the loft; and I think, from what I can gather, they were Dad’s. The wire is coiled, like a spring, and they sound wonderful. Warm. That’s what people say about music. You read it in the NME, when they’re talking about how an album sounds. The recording sounds so warm.

It’s time for a new mixtape. I take a blank cassette, one of the few that’s not been used yet. I don’t want ghosting, where you can hear the sound of what was on the tape before sneaking through, like a reminder in the gaps between the songs; or worse, underneath it all, in the quiet parts. I’m going to ask Shawn for his address and send him it. He deserves a fresh one: a C90, forty-five minutes a side. The perfect length. I unwrap the plastic from it, and pull open the case. Everything is ritual. There’s nothing better than a clean inlay card. I pick my cassette brand because it has the best ones. Sony, always. Always. Maxell if you can’t get Sony, but the Sony ones, there’s enough space to write ten song names on each side, even though I only usually go to eight or nine. The songs have to fill the full hour and a half. No random cutting off, no breaks or pauses. That makes getting the track list perfect a bit of an act of clinical perfection. Sometimes, somebody from school will make me a tape, and they’ll be so amateurish. You’ll get to the end of side A – usually struggling through iffy taste, at best – and you’ll hear the start of a song you know is going to cut off because there just isn’t enough time to finish it, like I’ve got a sixth sense of song length. Then, you flip their tape over, and either they’ve repeated that song, because they think they have to, or they just give me the second half of it, which is next to useless. And there’s no art to their tapes. You have to pick the song at the end of a side carefully. Because the tape is thinner, or weaker, or something, and it distorts there, so you need to go quieter with it. Don’t pick something that will distort. You need to structure it like a proper album as well. Nobody ends on a single.

Track one: Radiohead. I think there’s a Radiohead on every tape I’ve ever made. Hard to pick the right song, though. It needs to be something rare enough that it’s not obvious, but not so weird it sounds freakish. The first song is the most important choice you’ll make. Most important apart from the last one, that is.

I listen to their songs, to the first few moments of every song. Settle on the one I’m going to use – a B-side, but it was also on the soundtrack to Romeo & Juliet, which isn’t me dropping a message, but then also it kind of is. I sync the tapes up, and I press play on one, record on the other. Let them go, let the sound flow across while I listen to it. I picture it, for a second: not as data being copied over, but as those sound waves. Copying the intent, the emotions, the performances. An act of creation.

Track two is even harder. This is where you can lose your listener; where you need to pin them to their headphones. This is where you play the single.

I go for an old song. Something with meaning. My fingers flick through the cassettes, rest on my Kate Bush tape. My dad recorded this for me, from his vinyl. It’s still got the crackle, this tiny skip at the end. I put on my favourite song from it – I still dream, the first line goes – and that’s the one. I still dream of Organon.

I named my imaginary friend after the song. I dreamed of him, and then there he was. So when I was looking for a name for my bit of software, it seemed to be the only logical choice. I told myself I’d change it, but I never did. It stuck.

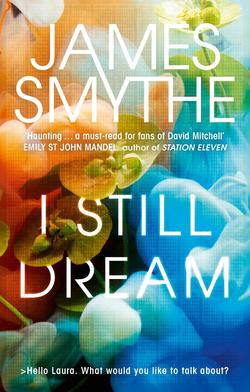

The screen changes to a blank space; slightly off-white, like a very, very light grey. It’s calming, which is what I was going for. In the middle of the off-white there’s a text box, just sort of floating there. Some words fade into it: the ones I’ve programmed the software to start with every time.

> Hello Laura. What would you like to talk about?

So I do what I’ve done every night of my life for the last six months: I tell my computer what I’ve done today, what’s happened and what I’ve felt. Everything, because that’s what the point of Organon is. Somewhere to log my memories, to keep them all recorded. To get my thoughts out, and to see them there. And kind of poke them, as well.

Then, when I’ve told it about school and Shawn’s emails and the BT bill and my parents shutting me off from the Internet, Organon asks me questions.

> How does getting an email from Shawn make you feel?

> Don’t you think your mother is only trying to help?

> Why do you hurt yourself?

I remember going to have casual-sit-down-cup-of-tea-and-a-chats – that’s what Mum called them, because she didn’t want to admit that we were in therapy – with this woman, in the months after my dad went missing. She lived near the park, only a few streets away from home, and every time I saw her she made me a mug of hot chocolate, even when it was sweltering outside, and we went and sat in her conservatory and talked about how I was feeling. Back then, I thought she was just a nice lady who was taking an interest. I didn’t understand what she was actually doing. How much it made a difference, or how much it felt like it did. And that’s what Organon is. That’s what it does. It doesn’t judge you. It just asks questions, and you give it answers. It won’t tell you if you’re right or wrong. I remember the woman – I can’t remember her name, but I can smell the chocolate, taste the nutty biscuits that felt like they were almost so full of health-food stuff they might be good for me – saying, How does that make you feel? But not telling me how it should. There wasn’t a wrong answer. That’s Organon, kind of. Almost. But then, sometimes, it tries to help you see what you’re talking about. If you’ve got a lot to say, it’ll dig deeper. If you use a lot of key phrases, it’ll work out what’s important, and keep nudging in that direction. That’s what I want it to be able to do, in the end. Somebody – something – you can just spill to, get everything out, and hopefully get something back. Maybe it’ll help you work out who you are. If it can understand you, it can do that, I suppose.

I hope.

Thing is, the therapist would forget. You’d tell her something, and sometimes you’d have to tell her again. And it was obvious that it wasn’t her helping me; it was me helping myself, after a while. I was seven years old, and even I could tell that. That’s where Organon improves on things, or can. The real beauty of a computer – where they’re better than us, even – is that it’ll remember something for ever, if you want it to.