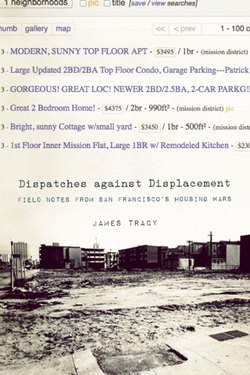

Читать книгу Dispatches Against Displacement - James Tracy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction: Of Delivery Trucks & Landlord Pickets

ОглавлениеI DREAM’D in a dream,

I saw a city invincible to the attacks of the whole of the rest of the earth;

I dream’d that was the new City of Friends.

—Walt Whitman

The housing crisis doesn’t exist because the system isn’t working. It exists because that’s the way the system works.

—Herbert Marcuse

First, a disclaimer: this is a partisan book. With the exceptions of the histories that occurred long before I was born, I was either directly in the fray or close by as events unfolded. In order for this book to be useful, I’ve had to turn a critical eye on people, organizations, and movements near and dear to my heart. This should be read as an organizer’s notebook rather than a comprehensive history of the housing fights in San Francisco. Books brimming with New Urbanism’s quixotic detachment can be found to the left and the right of this one on the shelves of your local bookstore. My urbanism is steeped in the politics of the human right of housing, to the city.

What do I want for the people whose stories populate this book? I want them to win.

In 1992, I drove a delivery truck for a thrift store in San Francisco’s Mission District. I’d loved San Francisco from afar for years, growing up half an hour north. On a typical day, we could pick up a sofa in the Bayview District bric-a-brac on Potrero Hill, and then steal a long lunch staring into the Pacific Ocean. We didn’t just learn how San Francisco’s neighborhoods connected or where to get the best cheap Chinese food or Russian perogies; we were let in on a secret: the mythical San Francisco, the tolerant land of opportunity and wonder, was about to burst at the seams.

In every neighborhood, we received curious donations: the abandoned belongings of the evicted. This was just prior to the official acknowledgement that San Francisco was entering a housing crisis, yet all of the indications were in the back of our truck. The wardrobe left behind by an elderly woman in the Richmond. Children’s toys in the Mission. Occasionally, the landlord would brag about the ouster. One told us, “It took me four months to get them out because of rent control.”

“Where did they go?” I asked.

“Oh, there’s plenty of public housing. I’m sure they will do fine,” he replied.

My co-worker John, who was a little older than I was, was a confirmed socialist. He had quite a reputation as the kind of guy who would show up, newspaper in hand at a rally and denounce everyone around for being soft on capitalism. I never saw this side of him. When we talked about what we were seeing on the job, he would encourage me to read about the unemployed workers’ movements of the Great Depression, where thousands of neighbors militantly defended each other from eviction. He convinced me to read Engels’s “The Housing Question.”1

My activist feet had been wet since high school, politicized through a combination of punk rock, fear of nuclear weapons, and an aborted Nazi skinhead invasion of my hometown. Because of what we saw every day on the job, right to housing stuck in my gut. On the truck I came up with a plan: we would organize tenant councils around specific evictions happening in their buildings or neighborhoods. These tenant councils would form a network, which would then work in solidarity with others for the long-term. The Eviction Defense Network (EDN) was born.

Because I was young, I was certain that no one in San Francisco besides our young organization knew what was to be done. In my mind at the time, the existing tenant rights community was too fixated on electoral fights to be of much use. I believed that affordable housing providers simply compromised politically. (Today, from the vantage point of a nonprofit job, I’m fully aware of my self-righteousness and lack of nuance.)

The EDN played an important role in San Francisco for a while. We were relentlessly independent. Funding a small office and phone with “Rock Against Rent” benefits at a local bar allowed us a degree of autonomy not granted to city-funded organizations. If your grandmother were being evicted, we’d go picket her landlord’s home. If a person with AIDS were being tossed out, we’d find the landlord’s business and shut it down. We were a pain in the ass and proud of it. We never succeeded in building the type of tenant syndicalism we envisioned, but our actions had an impact. Often, the extra pressure would prevent an eviction or at least leverage relocation efforts. When the landlords managed to place a rent control repeal on the ballot, we even ditched our dogmatic stance on electoral politics and joined with others in the tenant movement and helped beat it back by a big majority.

Because of our independence and chutzpah, eventually tenants of public housing reached out for us to join them in their corner of the housing crisis. Their problems were much different than that of the tenants in the private market who we were already working with. Instead of being pushed out solely for private profits, these tenants were caught up in an intricate web of privatization and structural racism. The Clinton administration (as you will read in Chapter 1) decided that the way to deal with public housing’s problems was with a wrecking ball. A typical plan would preclude most of the tenants from returning.

As I got to know the community of North Beach public housing, I learned from them the history of the “other” San Francisco. In 1942, southern black workers were recruited to work in World War II industries in the Bay Area. In San Francisco they settled in the Fillmore District, housed in the homes of Japanese people interned after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Post-war, the Fillmore thrived with black small businesses, jazz clubs, and a strong community. However, this too was not allowed to stand.

The Urban Renewal Act of 1949 allowed local governments to create redevelopment agencies that were able to seize private property through powers of eminent domain. All that was needed was the declaration that a neighborhood was blighted. The fact that the Fillmore had very little blight did not deter the San Francisco Housing Authority from a demolition rampage that displaced over 17,000 residents.

As an outsider, it was impossible to effectively organize alongside public housing residents without understanding the generational impacts of displacement. It would have been easy for me to frame the crisis in terms of cold public policy or my radical utopian aspirations. But for the people I was working with, displacement was just part of a long history of racism and to some minds a genocidal master plan.2

This experience changed me, turning me into the type of urbanist I am today. At the beginning, I didn’t understand the finer contours of institutional racism. If I ever fixate too much on the impacts of white supremacy in the city, it’s because of the stories tenants shared of regular displacement and discrimination.

My love of cities is untarnished and still a little romantic. The city is a place where people from all over the world are concentrated and have the potential to meet and make common cause. Seeing the twin engines of displacement through the market with that of the state has made me extremely leery of complete reliance on either as the only solution for the urban crisis. Today, despite many dozens of well-fought campaigns, San Francisco is even more exclusive and expensive. A modest two-bedroom apartment rents for about $4,000. The city as it is developed and redeveloped bears little resemblance to elected officials’ rhetoric about a sharing economy.3

Cities simultaneously and effortlessly embrace both utopian and dystopian potentials. Most of them were born from human-caused ecological disasters—the clear cutting of forests, the paving of rivers and creeks. Today, the solutions to climate change are in part urban. Density can prevent sprawl and robust public transportation is the best way to cleave drivers from private automobiles. Through zoning and redlining, the political economy of cities has always been shaped by racism and white supremacy. It is in cities where oppressed people most often find each other, demand self-determination, and often forge coalitions. Dour, alienated architecture argues with vibrant design. Cities offer up the worst that popular culture can conjure and also give birth to rebel music such as hip-hop and punk, which in turn become the mass culture of another decade. Displacement replaces radical potential with spectacle. It is the change that kills off all other positive changes.

It doesn’t really matter if one likes or dislikes cities. In 2008, for the first time, the percentage of the world’s population living in cities outpaced those living in rural areas, and that population is likely to grow for the next few decades.4 This makes questions about who governs, lives in, and is excluded from cities all the more critical to those who wish to chart a course for a more egalitarian world.

Throughout this book, I use the word “displacement” instead of “gentrification” in order to emphasize the result of uncontrolled property speculation and the impacts this process has on everyday people. The definition of “gentrification” in the Merriam-Webster dictionary is precise enough: the process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces poorer residents. However, the way the term is used often lacks the same precision. It is not uncommon to hear, as one liberal San Francisco supervisor opined, “A little gentrification is a good thing.” Worlds of contradictions live within this deceptively simple sentence. What is usually meant is that neighborhoods need certain things, like grocery stores and basic infrastructure, to be whole, and that speaker can imagine only the arrival of affluent newcomers as the catalyst for this. It assumes that gentrification is as natural as granola, instead of a deliberate real estate strategy. Let’s assume then that at least some of the people who profess to want gentrification really simply want a thriving neighborhood sans displacement. The final chapter, “Toward an Alternative Urbanism,” offers some ideas about how to fight for development without displacement.

What to do now that cities are not feared in the way that they were fifty years ago? Politicians and pundits frame displacement as either an unfortunate side effect of urban progress or—in unguarded moments—a welcome cleansing. But it doesn’t have to be this way; cities can grow, change, and welcome new citizens without running roughshod over the existing population. It is a mistake to frame anti-displacement politics as anti-change. After all, change is one of the things that made cities interesting places to live in the first place. Immigrants fleeing Latin American death squads and poverty represented change in the Mission District. The difference then was that the old-school Irish, Italian, and Jewish residents did not leave the neighborhood under the duress of an eviction notice. Working-class blacks who arrived in cities during the southern diaspora not only contributed their labor but also helped develop a strong urban cultural life. Those who come to a city fleeing homophobia, wanting to start a band, or to go to school are exactly what a good city is built upon. How then have monoculture and commodity come to dominate?

If the working-class spine of a city is broken, then no one but the moneyed get to dream big dreams in the city.

These dispatches defend the communities that make cities an amazing place to live: the working classes, artists, immigrants, and communities of color. They also make two modest proposals: first, that extending to the excluded the right to the city benefits all, and second, that excluded people can be active participants in building better cities, not just passive beneficiaries of progressive social policies.

The idea of the “right to the city” stems from the writings of Henri Lefebvre, an unorthodox Marxist who proposed that cities were the primary sites of contestation between capital and working-class movements.5 This came as a bit of a shock to his contemporaries, who prioritized struggle at the point of production, such as factories. Today, with so few factories left in “First World” cities, Lefebvre’s work is nothing short of prophetic. Alongside the conflicts over the production of goods, cities are also the sites of clashes over the production of space (campaigns against luxury housing and for neighborhood protections), services (domestic and fast food workers), and human rights (immigrant rights, school-to-prison pipeline organizing). Central to the idea is that “everyone, particularly the disenfranchised, not only has a right to the city, but as inhabitants, have a right to shape it, design it, and operationalize an urban human rights agenda.”6 Thanks to their direct engagement with grassroots organizations, Lefebvre’s intellectual descendants have had an enormous influence on contemporary urban organizing; thinkers such David Harvey, Peter Marcuse, and Harmony Goldberg have been central to popularizing, updating, critiquing, and challenging Lefbvre’s vision.

Today, the right to the city has truly never been further away from reality. Every year, the National Housing Law Project (NHLP) produces Out of Reach, a survey of housing costs, unique because of its emphasis on the links between wages and housing. Its methodology is based on what an average worker must make in order to afford a two-bedroom apartment, a figure they call the Housing Wage. The report has consistently shown that rents far outpace the means to pay not only in high-investment, hyper-gentrified cities like San Francisco, but also in shrinking cities such as Detroit. In 2014, the national Housing Wage is $18.92 per hour, which means there is no state in the entire United States where a typical low-income worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment. San Francisco’s Housing Wage is $37.62, almost four times the municipal minimum hourly wage of $10.74. If current campaigns to raise the minimum wage to $15 prevail, the wage-to-rent gap will still render most housing in the private market out of reach for many.7

Perhaps the moment when one becomes a political radical is the day one stops blaming all of the two-bit players for the problem and starts hating the game. Some of the individual landlords the EDN protested weren’t just greedy, they were a cog in a much more complex urban machine—though I still don’t have a problem with camping outside of a mansion to bring the crisis of displacement to the doorstep of a landlord. The system of real estate practiced in the United States in a dismal one, a cocktail of some of the worst features of serfdom and feudalism. Some of the landlords we pestered were small potatoes—part of the sandwich generation who had to simultaneously take care of parents and children. They bought rental property when it was cheap and they had decent jobs and wanted to cash in on their investment. With the money flooding in from the first dot.com rush, it was hard for small property owners not to. Some didn’t feel like they had a choice. The profits represented college tuitions for their kids, an early retirement, health care and elder care. It was the real estate industry that relentlessly marketed San Francisco as the new frontier.

It wasn’t uncommon for advertisements to read, “Be a pioneer in the former Wild West of the Mission District,” or, “Up and coming neighborhood ready for a new sheriff in town.” As someone who moved sofas for the minimum wage, I couldn’t understand how in hot hell I could be part of the gentrification problem. But just as pioneers were manipulated by robber barons to clear the West, the presence of non-affluent artists, politicos, and punk rockers was needed to soften up the neighborhood.

Beyond the presence of the tattooed and the restless, there was something else going on: it was neoliberalism, something that my generation of activists associated with Chiapas or Bolivia but rarely connected to the home front.

In 1999, the American Friends Service Committee asked me to travel to Seattle to cover the WTO protests for their magazine Street Spirit. Thanks in part to the Zapatistas, the term “neoliberalism” was on everyone’s tongue. I struggled with this; I thought it was strange that so many people who wanted to change the world ignored what was going on in their own backyards. After all, if neoliberalism was simply capitalism with the happy face torn off, weren’t there plenty of signs of it in San Francisco?

“Neoliberalism” is one of the most abused terms in the political lexicon. Like “fascism,” it is hurled as an epithet against any form of disagreeable political or economic activity. Simply put, neoliberalism is both an ideology and an economic strategy aimed at deregulating corporations, removing barriers to trade and commerce, and privatizing public resources. Commonly associated with international trade, neoliberalism has found a second home domestically, imbedding itself in the governance of major American cities.

San Francisco’s economy has often been held hostage by neoliberal thinking, in turn fueling displacement and causing economic well-being and cultural diversity of communities to suffer. In 2001, fifty-two corporations sued the city of San Francisco over a dual payroll–gross receipts tax. The Board of Supervisors, fearing that the suit would bankrupt the city, voted to approve an $80 million settlement. The city paid for this by selling general obligation bonds—meaning that it sucked close to $100 million dollars out of the city coffers in tough economic times. The subsequent years were marked by severe budget cuts to housing, health care, and other essential services.

It would be a mistake, though, to say that the corporate agenda has ruled San Francisco without challenge and compromise. Grassroots organizing has extended workers’ rights and protections to non-unionized service workers through municipal minimum wage and anti-wage-theft ordinances. The city boasts 26,000 units of permanently affordable housing. San Francisco even has its own form of universal health coverage for its residents, regardless of formal citizenship or ability to pay. And, despite the best efforts of the landlord lobby, rent control still offers basic protections for renters who live in buildings built before 1979.8

Yet the fact that San Francisco is even more exclusive and expensive can be traced directly to the embrace of neoliberalism in a progressive city. In 2011, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors granted a tax holiday to Twitter, Inc., the micro-blogging and social networking company founded in the city. Twitter threatened to move south to neighboring Brisbane unless its municipal payroll taxes were forgiven. Local politicians responded not only by granting a $22 million dollar tax break but by also approving a plan that has contributed to displacement citywide. At the time of the tax break, the deal was valued at between $4 billion and $6 billion.

Initial legislation proposed by Mayor Ed Lee would have given Twitter a complete payroll tax break in exchange for sticking around. Modified legislation, which passed, put forward by Supervisor Jane Kim, granted a six-year payroll exemption only for new hires and created an “enterprise zone” (including Twitter’s new digs) on struggling Market Street and in parts of the Tenderloin and South of Market neighborhoods. The tax break extended to all businesses starting up in, or relocating to, the zone.

The enterprise zone economic development strategy grants corporations tax breaks and other advantages in exchange for doing business in an economically downtrodden neighborhood. Even though it is a conservative approach, based on incentives, most enterprise zones at least require the beneficiary businesses to commit to certain levels of local hiring and other community benefits. One problem is that after four decades of existence, they have shown little positive impact. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, employment rates within enterprise zones are no different than similar areas outside of them.9

The Twitter agreement didn’t secure any benefits in a specific, legally binding manner. Tech companies have been widely criticized for promoting media stunts such as community cleanup days in place of grassroots economic development initiatives. Steve Woo, a community organizer with the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation, remarked, “The enterprise zone in the middle of Market Street was created by city officials without any specific commitment of addressing [the community’s] needs and instead prioritized the needs of Big Business.”

Even a progressive official such as Kim, who described herself as philosophically against such tax breaks, felt that she had to do business with Twitter. She pointed out in a public hearing that, without the legislation, all of the revenue from Twitter’s payroll tax would leave San Francisco for the suburbs, and four hundred jobs would disappear from the local economy. Three years later, the tax break has cost the city $56 million. Advocates for the legislation pointed to the boarded-up storefronts on Market Street, and to the “seediness” of the area, claiming it was ripe for renewal. Kim was right—the choice to grant tax breaks was one choice among many that were all nearly as bad. It is a shining example that neoliberalism isn’t just an economic strategy but also works to narrow what people see as possible options. After all, progressives hadn’t put forward their own plan to breath life into boarded-up Market Street—it’s no surprise that new money allied with old corporate property owners and built a coalition to reap massive profits with little thought to community impact.

Other community voices, such as the South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), cited fears of displacement from a second dot-com economic boom. Neighborhoods bordering the “Twitter Zone” are largely working class and consist predominantly of renters. Supporters of the zone pointed out that these neighborhoods were in need of jobs and uplift and argued that because of decades of progressive zoning changes the neighborhoods were immune to gentrification.

The Twitter tax break has proved that many of the community’s fears are correct. A non-subsidized one-bedroom apartment in the neighboring South of Market area starts at about $2,800 and can rent for as much as $8,000 a month. Angelica Cabande of SOMCAN, who led the attempt to defeat the Twitter tax break, explained, “City and state officials have been preaching that everyone needs to buckle down and make responsible decisions and make due sacrifices for the betterment of everyone; it doesn’t make sense that big companies like Twitter get a tax break.” Such is the dilemma facing politicians and policy makers. Employers like Twitter are able to move their offices much more easily than factories and plants did in the past, and this, combined with the current dearth of large employers, leaves cities hostage to corporate demands. It’s the neoliberal economic model applied to local neighborhoods.

Twitter’s economic blackmail has started a trend. Even before the ink had dried on this deal, another company, Zynga.com, delivered a demand of its own: stop taxing stock options, they told the city. Again the Board of Supervisors and the mayor obliged. What this is may be as simple as the politics of a hostage situation: give us the money or we’ll kill the jobs. As you will read, the neoliberal fingerprints are also found all over the demolition of public housing and the weakening of rent control protections.

Looking for the North Star: Radical Community Organizing in the 1990s Bay Area

When I first started organizing, many veteran activists took it upon themselves to buy me a copy of Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals. At one point, I had about a dozen copies on my bookshelf, all of which remained unopened until the latter part of the decade. Although community organizing had been going on in the United States since the first Native uprising, Alinsky, a brilliant and cantankerous Jewish man from Chicago, was often portrayed as its “godfather.” In the early 1990s, several authors and organizers were starting to question Alinsky’s large footprint on social justice work, pointing out a conflicted history of racial justice as well as an economy that was shifting from surplus to austerity.10

What Alinsky contributed was a coherent model, a set of tactics and strategies that were appropriate to large portions of America’s working and middle classes in post-WWII America. He was not ambivalent about the need to shift power away from what today’s activists call the 1 percent toward the 99 percent. Alinsky upheld that conflict, embodied in creative direct action, was essential in empowering the powerless.11 He advocated permanent organizations, rooted in neighborhoods. He wasn’t a Leninist and despised authoritarian versions of socialism. He believed that economic inequality within capitalism would always destroy the potential for freedom. In that sense, he would have been a logical grandfather for a new generation of anti-authoritarian organizers.12 The fact that so many of the organizations that still upheld Alinsky seemed to be tied to the Democratic Party prevented us from a serious study of his ideas.13

He was a complex thinker, and I encourage anyone whose understanding of Alinsky stems from either right-wing Obama conspiracy theories or left-wing diatribes to get to know him in his own words. Alinsky was firmly a man of the progressive left and would have been saddened to know that people who wanted to reinforce the privileges of the already intensely privileged used his teachings.14

Alinsky believed that the United States held unlimited potential for deep democracy. He was a patriot who encouraged organizers to build on beliefs and traditions of the people they organize and situate their stories within American democratic traditions. This would later put him at odds with those radical organizers inspired by Third World revolutions, who had arrived at the conclusion that the United States was an unreformable and oppressive power, corrupt to the core. When considering Alinsky’s importance today, it is more useful to focus on the challenges he posed to organizers, rather than on some of his own flawed conclusions. What forms of radicalism can everyday people actually relate to? How do you organize in a country where most workers identify with, or aspire to be part of, the middle class?15

Much has been written about Alinsky’s struggles with organizing in the context of racialized capitalism. It’s worth exploring this in order to gain an understanding of why so many activists of my generation discounted his importance—and also to complicate simplistic interpretations of his chauvinism. Alinsky’s signature organizing project was in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood, the one made famous by Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle.16 The neighborhood council he created, the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC), helped to transform a beaten down area into a healthier (white) working-class area with improved housing, social services, and improved conditions in the neighborhood’s warehouses.

Alinsky’s critics point out that his reluctance to face race with working-class whites allowed the virus of white supremacy to fester. Alinsky’s friend and biographer Nicholas Von Hoffman commented on the irony that BYNC’s motto was “We the people will determine our own destiny,” and that destiny was purely white.17 The same community organizing skills used to improve the neighborhood could be employed in the service of reactionary racism. This pointed to one of the limits of the Alinsky model, which was dependent on winning the favor of established institutions like churches and unions. If these institutions were contaminated with racism, so would be the community organization they supported.

Alinsky hated this state of affairs but was ultimately caught inside the box of his own framework. Too much of what we now call popular education integrated into organizing struck him as patronizing—too similar to the ideologically rigid methods of the Communist Party USA.18 He honestly believed that organized people would ultimately make the best decisions. This is can be true in many instances, but white supremacy proved itself to be a durable project. Groups such as the Center for Third World Organizing were pivotal in advancing the critique of Alinsky-inspired organizations and making a space for organizers of color to advance their leadership.

If not Alinsky, then what?

Many of the most committed organizers of the 1960s and 1970s had formed the “New Communist Movement” (NCM), which attempted to build the conditions for a Marxist-Leninist party to emerge and guide the nation toward a revolutionary overthrow of the government and capitalism. The character of NCM organizations varied greatly, from earnest working revolutionaries to cult-of-personality demagogues. What united most groups were roots in the 1960s civil rights, anti-war, and student struggles, an analysis that US imperialism was the enemy, and animosity to the idea of “reformism.”19 Throughout the Reagan years, many of these organizations kept left organizing alive through participation in workplace struggles, anti-apartheid organizing, and work against US intervention in Central and South America.

Many of us had contact with these organizers, but ran shrieking at the possibility of actually becoming cadre—for both good and bad reasons. We weren’t stupid enough to believe that criticism of existing forms of communism were simply capitalist propaganda. As young rebels, we questioned the need for secretive and hierarchical leadership forms empowering a small group of leaders. At least in the beginning of our political involvement, my generation of organizers lacked the ideological compass that our predecessors possessed. We knew what we were against but had a hard time articulating what we were for. Were we for radical inclusion or a revolution? In some cases, our ambiguity allowed for a positive experimental approach to organizing, far more accountable to the people we were working with than the vague and mutable ideas of a future revolution. It equipped us for the type of organizing rooted in the politics of door-by-door, face-to-face conversations. It also left us in times of crisis trying to guide a ship without a rudder, ill equipped to answer many of the important questions arising in our work, such as the role of the state and the place of reform in the larger picture of social change.20 Even if we initially lacked a grand unifying theory of social change, my generation of activists had strong international, national, and local influences on our ideas of social justice, starting in the decade in which we came of age—the 1980s.

During the Reagan years, many of the most catalyzing political movements were communicated through the lens of identity politics—battles against racism and homophobia, and for reproductive rights. Campaigns against US intervention in Latin America and in support of South Africa’s apartheid regime also brought many into activism.

As Black South Africans fought to end racial apartheid, the international movement toward boycotts, divestment, and sanctions captured the imagination of many around the world, especially those in the San Francisco Bay Area. This solidarity movement was at its best when it drew connections between local and international racism. It also revealed the complicity of the United States in upholding apartheid, and at the same time provided ample opportunities for local action. Department stores selling South African gold krugerrands were protested, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union refused to unload South African cargo imports. Organizing against apartheid put the conversation about race in the center of our emerging worldviews. Groups such as Anti-Racist Action, Red and Anarchist Skinheads, and others militantly confronted a resurgent white nationalist movement exemplified by White Aryan Resistance, Stormfront, and various smaller neo-Nazi groups, reminding many that the United States had not yet awakened from its own racial nightmare.

At that time, the religious right also began its own form of civil disobedience, through blockades at women’s health clinics. The Clinic Defense (or Clinic Escort) movement brought forth a new generation of pro-feminist, pro-choice, pro–direct action activists.

Solidarity work confronting US military intervention was front and center in the 1980s and 1990s. Groups such as Committee in Support of the People of El Salvador and the Nicaraguan Institute for Community Action regularly sent delegations to Latin America in hopes that “brigadistas” would build an anti-imperialist movement upon their return to the States. These efforts were often the beginning of political consciousness for young North Americans. Related to this was the Sanctuary Movement, a mostly faith-based Underground Railroad for refugees of US proxy wars in the Central America.21

The emergence of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and Queer Nation revitalized queer politics, with a focus on nonviolent direct action methods. Growing up in the Bay Area, it was rare to not know someone who had contracted HIV/AIDS, and ACT-UP’s uncompromising spirit inspired many.22 Queer Nation also made an impact by insisting on visibility in the Bay Area’s suburbs—holding kiss-ins at malls and sports events. Taken together, these big-picture movements helped shape the worldviews of those who would become involved with community organizing in the coming years.

The last decade of the twentieth century was turbulent from its beginning. In 1990, the first invasion of Iraq, under George Bush Senior, brought many thousands of people to the streets. America’s racial tinderbox was ignited once again in 1992, when police offers involved in the beating of Rodney King, a black motorist, were acquitted, resulting in the Los Angeles rebellions. And once again, in 1992, color and hue became central to the activist conversation as indigenous organizers brought forth a series of colorful and often confrontational mobilizations on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the “new” world. For those of us who were struggling to contextualize these upsurges within our own experiences, we arrived at conclusions strikingly similar to our 1960s counterparts: the system of imperialism had both external and internal expressions.

In 1994, Congress passed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the most visible critics of which were a group of revolutionaries in Chiapas, Mexico, who launched an armed occupation of seven Mexican towns to protest the actual and cultural genocide resulting from free trade. To say that the Zapatista Army of National Liberation was inspiring to North American activists is an understatement. Their theory of “leadership through obedience” came with a set of powerful stories and narratives. The story of dogmatic revolutionaries going to the mountains to recruit indigenous people into a political party, only to have their own practice transformed seemed to at least temporarily address the problems we had at home between strict top-down organizations and the covertly hierarchical consensus-based organizing.23 It never fully addressed the problem, serving more as an ethical benchmark than a replicable organizing model. When the EDN was invited to work with residents of public housing, many of us were convinced that we could simply emulate the Zapatistas. Like many before us, we took a great example from another land and attempted to apply it mechanically to our own situations. (Probably not what Subcomandante Marcos or Comandante Ramona had in mind.)24

The pitched protest movements confronting right-wing attacks on the inclusive social progress of the 1960s and ’70s and international revolutionary movements inspired my generation of organizers. Those of us who chose to operate on the neighborhood level believed that we were in fact connecting the dots between the global and the local, confronting the impacts of the global economy, racism, and a rising right in the neighborhoods we lived and worked in.

Throughout my life, I’ve seen moments like this through the battles for home and public space. They are always fleeting, as are the tenuous alliances that bloom and wilt again. Neoliberalism has literally stolen the city from those who most contribute to its vibrancy. While things will never be (and maybe never should) be the same, resistance—not only capital—shapes urbanism.