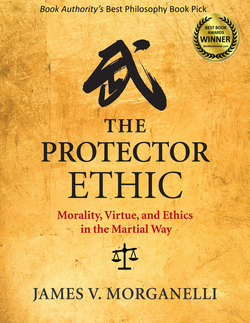

Читать книгу The Protector Ethic - James V. Morganelli - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Moral-Physical Philosophy

ОглавлениеSome believe the ethical and tactical are mutually exclusive, even incompatible. The tactical is about survival, they’ll say—“Kill or be killed.” The ethical is for Sunday school or philosophers, who rarely, if ever, get punched in the face. But this is hardly true—I get punched all the time.

Anytime someone decides to begin martial training, the decision itself is of an ethical nature. Take the three most basic questions anyone who trains must answer:

What am I going to learn?

How am I going to learn it?

Whom am I going to learn from?

These considerations only gain in importance because they do not just inhabit teaching lives; they haunt them:

What am I going to teach?

How am I going to teach it?

Whom am I going to teach?

We answer these questions regardless of our awareness or ignorance of them because choosing to train in martial arts is our vote for the “what, how, and whom.” These questions further call for direction, not just for knowledge of techniques but also for the manner of their use. Manners relate to a person’s qualities, and qualities relate to character. “Manners are of more importance than laws,” the philosopher Edmund Burke wrote. “Manners are what vex or soothe, corrupt or purify, exalt or debase, barbarize or refine us, by a constant, steady, uniform, insensible operation, like that of the air we breathe in.”2 No one can engage the martial without being subjected to the modification of character.

Training does not automatically moralize us just because we do it. It only grants us the opportunity, provided we affix training to its virtuous, life-protecting design. Unless students are faced with the inherent duties of the protector ethic, training is nothing but selfish endeavor. One that can become incomprehensible if we purposely obscure its path due to our own penchant for amusement, or, worse, outright refusal to follow the path where it’s taking us. The biggest concern anyone should have with training is the obsession with technical information—techniques—which is symptomatic of the excessive focus on the self and the continual satisfaction of the ego. Perhaps you’ve heard martial arts destroys the ego, but this is silly. People need a healthy ego to thrive. Training functions as a temper, and it does so by balancing our needs and wants with humility stemming from our duties to self and others.

When training gets selfish, it can grow dark and twisted, a place where everyone is a potential enemy, including people we care about. Instead of becoming that happier, healthier, brighter light to the world that others look to for strength and guidance, we dim, obscured by shadows of our own making. And it’s only in this darkness that the bloodline of the martial way is misidentified as mere “killing arts.” This has the effect of diminishing it, severing the link between tactical strategies and their original, life-protecting principles. The account departs from any sense of responsibility and appeals, perhaps unwittingly, to a base appetite for “might makes right,” a self-satisfaction that degrades training as amoral, neither ethical nor unethical. If it’s neither right nor wrong, it’s just a cold, hard tool that makes it easy to kill.

Now, do not misunderstand me. The knowledge and material ability to kill an enemy hold an immeasurably important place—sacred, even—in martial means and ways. In many respects, maturity in the martial way is paradoxical, as in “learning to die in order to live” or “killing to protect life.” These notions are intrinsic to advanced studies, but because they are not simple to comprehend, let alone physically embody, they are easily misunderstood. And the easiest to misinterpret is the martial as merely mortal.

The fate of the feudal and ancient world was indiscriminate death. People died young, sick, and infirm, as they were plagued by plagues, starved, hunted, and massacred between tribes and clans. History’s brutality is legendary. It was the martial way that tipped the balance to protect and sustain life. Is there any question as to why the warrior class would ascend to the preeminent cultural position throughout antiquity? It wasn’t because the warrior was renowned for his death dealing, but his life protecting. Death was commonplace. Life was special.

If the guiding value of the martial way is only the killing of the enemy, then how do we explain the fact that these ancient arts retain the tactical calculations in order to live through battling an enemy, even though killing may be necessary? It is always far easier to kill and train to kill when one’s life is sacrificial to that goal. Terrorism’s use of the suicide bomb is first and foremost for killing because its aim places it above even the life of the bomber. But the martial way actually coheres to human nature’s life-preserving instincts—even a survival martial art is qualified by the value-of-life notion, survival.

When we depict and participate willingly in a so-called killing art, we revoke training’s ethical standard. And even if we acknowledge the standard, if we don’t train, articulate, and rely on it, we leave it to the misinformed and uninitiated to use its absence against us in a court of public opinion. And, worse, perhaps one dark day in an actual court, where the fearful among us will state the argument for its abolition. It wouldn’t be the first time.

The way of the martial is moral. Whenever we use it, train in it, or teach it to others, we deal with the ethical, the moral in action. And the protector ethic is the outstanding bond, the summit of its endeavor, why it all matters in the first place. Believe it or don’t—the martial way is ruled from within the realm of ethics.

Every physical technique and tactic, every philosophical and strategic conjugation of use, is contingent on this singular point. It is the self-evident, undeniable way of the martial way.