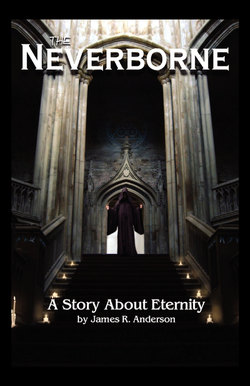

Читать книгу The Neverborne - James Anderson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4

ОглавлениеLasting’s Court in the Neverborne Kingdom

The powerful black robe named Lasting circled the highly polished obsidian floor of his main chamber. Each place he stepped, a crimson pool bled out from his footstep six inches in each direction and just as quickly subsided to shining blackness as the foot left the floor. His arms were folded in front of him so that each hand held the opposite shoulder. His eyes focused on the floor before him.

In aggravation, his steps quickened to an inhumanly quick rhythm. He was thinking about the same thing which had obsessed him for eons – his absolute hatred for the red robe Alaal, now Ruben Barlow.

At one end of the chamber, a spirit hung suspended in a cage. Each time Lasting passed, his right hand shot out and the cage was engulfed in a fireball. The poor spirit, whose only crime was to resemble Alaal, screamed in agony as his body was consumed with fire, only to regenerate when the fire died.

Lasting’s concentration was suddenly interrupted by a messenger, and Lasting’s hand extended threateningly toward the newcomer. The Neverborne neither understand nor practice tolerance.

“Your grace,” said the messenger, falling to his knees in fear. “I believe what you seek has been found.”

Lasting’s hand did not move. “A mortal?” he asked.

“Yes, your grace,” said the messenger, his forehead touching the floor.

“Has this mortal a relationship with the red robe Alaal?”

“No, your grace. But he is the same mortal age and lives in America.”

“America!” spat Lasting. “I hate America. Is the mortal susceptible to our nature? Will he do what I want?”

“We believe he will serve your purposes, your grace.”

“What is his mortal name?”

“William, your grace, called Billy by those who know him.”

“Billy” said Lasting to himself. “Show him to me.”

The messenger lifted his hands and showed Lasting his palms. “Behold, your grace.” Then, images began emerging from the extended hands.

Billy Harold

Boston, Massachusetts – 1961

“What are we supposed to do with you, Billy? Why do you read this tripe?” Mrs. Harold’s voice quivered with emotion as she held the book between her thumb and forefinger. Twelve-year-old Billy stood before her, his blue eyes glancing from knot to knot on the dark hardwood floor.

His father, sitting on the bed with his face in his hands, suddenly grabbed one of the many images of Christ that adorned every room of their Boston Victorian home and leapt to his feet. He gripped the black hair on the back of Billy’s head and pulled Billy’s eyes toward the beckoning arms of the six-inch statue.

“What would He say, Billy? What would the Lord God Almighty say about this filth?” His father violently jerked Billy’s head back and pain again engulfed the boy’s scalp. His father, still jerking Billy’s head, moved his face so close to Billy’s that their foreheads touched.

“Answer me, you blasphemous boy!” Billy felt his father’s spittle spray his face as the grip tightened and knew he needed to answer before his hair was pulled out.

“I was curious,” he said, in a barely audible whisper. His father suddenly released Billy’s hair and placed a huge hand on Billy’s shoulder. He turned his head so that his ear was directly in front of Billy’s mouth.

“What did you say?”

“I was curious,” Billy whispered. His father faced his wife and Billy was left to look at the solid field of white shirt covering his father’s broad back. His father’s hands rose toward the ceiling and struck the hanging overhead lamp. The lamp swung precariously two feet in each direction and Billy wondered if it was going to come crashing down on him. That was fine with Billy - it gave him something to concentrate on other than this latest parental tirade.

“Oh, well,” his father said in mock relief. “The boy was curious. That explains everything. The boy turns his back on everything good and holy, everything he’s been taught since we brought him into his world because he was curious. It’s all right, Mary. The boy was just curious.”

His mother’s large blue eyes were as wide open as possible. She took in a full breath of air in anticipation of a lengthy speech but, as if she suddenly changed her mind, held the breath as she stared in disbelief at her only son, her sholders at the apex. Her left hand shot out and encircled her husband’s hand and pulled it to her bosom as hand and statue sunk between her breasts. The statue’s arms, normally held out in welcome, now seemed to plead for help before death by suffocation. Billy could not help himself. The thought of suffocating between two breasts was just too funny for words so, try though he did, he could not stifle the laugh. There was a fairly large reserve of snot in his nose and, as he involuntarily brought his hands up to cover his mouth, all the air pressure from the laugh was redirected to his nasal passages and snot projected out of his nose at a perfect 45-degree angle, hemming his mother’s black skirt, coating her nylon-covered legs, and landing in blobs on the pointed toes of her black high heels.

As she exhaled, she seemed to implode. She looked down at her shoes and rasped, “Billy!”

His father, with one hand still buried, knocked Billy down with a powerful backhand. Billy knew this would come as it had so many times before. He left his feet, slammed into the wall, and fell in a heap on the bed. His ears were ringing and his head was filled with a sickening pain. Red lights trimmed with white exploded before his eyes and he lay in semi-consciousness.

“John,” his mother screamed, “Don’t hurt him!”

“Don’t hurt him? Why, Mary, I’m not going to hurt him. I’m just going to satisfy his curiosity!”

John Harold, dealer in heating oil and coal, handed the statue to his wife’s safekeeping and, snatching up the book entitled The Occult – from Aphrodisiacs to Witches, knelt before his youngest child. Taking the book so the back cover rested in his palm, thumb on one edge and little finger on the other, he grabbed Billy’s shirt.

“Here, son, take a good long look.” His father lifted him off the bed and slammed him down on the floor, the back of Billy’s head making a cracking sound against the hardwood. John Harold pushed the front cover of the book into Billy’s face and started grinding and rotating the book back and forth. Billy screamed out in pain and his mother heard crunching cartilage. Blood spurted from Billy’s nose and rolled down either side of his face, pooling on the floor.

His mother threw herself on her husband’s back, looping her arms around his bull-like neck as she tried to pull him off of her son. Her legs flailed in the air, searching for leverage to pull her husband back.

“Stop, John! You’ll kill him!” But her husband ignored her as huge muscles bulged, straining at their task.

Repositioning herself, she yelled in his ear, “Stop, John! Enough, enough!” Her husband heard and stopped. As he pulled the book away, it was covered with sticky, red fluid. A clot slipped off the underside of the book and landed sickeningly on the floor. Billy’s face was covered in gore. His head rotated instinctively, his mouth open as the only source of air. Between rotations, blood flowed from his nose into his mouth. As Billy coughed, red bubbles formed and popped between his lips.

John Harold looked questioningly at his wife. “I don’t know what to do anymore, Mary. He’s not my son. He can’t be my son. He’s some devil’s spawn put here to try my faith.” John Harold rose to his full six foot two inch frame. Sweat glistened on his forehead and he leaned menacingly toward his wife. For a moment, she thought he was going to strike her, again.

“I know he’s your son because you carried him for nine months. But, right now, that’s all I know.” He walked out of the room and into the hallway before he turned back to his wife.

“Since we know he’s your son, you deal with him. I’m going to read the Bible with the blood of the wicked still on my hands.” He held up two blood covered palms as if they were trophies. “I will kneel before Him in prayer, triumphant in His cause. You can clean up the mess.” He turned and walked away, breaking into a loud, off-key version of “Onward Christian Soldiers,” stomping his feet loudly in time with his singing. She heard the door to the study slam and knew he would not come out for several hours.

She knelt and forced herself to look at her son. He was lying on his back, his feet folded back underneath him, one shoe untied and partly off his foot. He was semi-conscious and his hands were instinctively covering his face. The flow of blood had partially stopped but he was still coughing. Tears made wet trails through the blood in the direction of the floor. As his mother rolled him over on his side to keep him from choking, a trickle of blood came from the corner of his mouth and dribbled onto the floor. Tears sprang to her eyes as she tried to reposition some of his blood-matted hair.

“Oh, Billy,” she whispered. “Dear, sweet Billy.” She helped him to his feet. He was conscious enough to move his legs as she guided him into bathroom. She soaked a washcloth with cold water and held it over his nose. When he opened his eyes, she saw the residual fear and began to reassure him.

“It’s OK, baby. He’s not here. We’re going to the hospital to get you better.”

She told him to hold the washcloth over his nose while she went to the refrigerator and wrapped ice in a dishtowel. Returning, she said, “You hold this ice over your nose while I get cleaned up. I’ll be right back.”

She left him on the floor of the bathroom with his head tilted back over the edge of the tub. His thoughts intermingled with the nausea and pain. His hatred for his father was a given, something he lived with, like some deformity. He loved his mother, he supposed. He was fairly sure she loved him; sometimes she just didn’t act like it.

His father provided a very comfortable living, and his mother took care of all the money. Billy supposed she was good with money because there was always enough for his father to do what he wanted: go to Bible retreats, boxing matches, or buy the magazines of naked women he kept locked in his desk. The bills were always paid, they ate and dressed well, and his father gave a substantial contribution to the First Pentecostal Church of Greater Boston every Sunday, fanning out the various bills and placing them in Reverend Popejoy’s hand as worshipers left the church. “Here you go, Reverend,” he would say loudly. “I’m paving the road to heaven with my good works.”

Billy had a sister from his father’s first marriage. His father’s first wife died from falling down stairs and breaking her neck. His father and mother never talked about it. His sister Grace was ten years older than he was, and only lived five miles away but never came over unless their father was gone.

When his father was away from home, his mother always called Grace to see if she would stay with Billy. She never refused. She would come over or sometimes his mother would drop him off at Grace’s apartment. Often, his mother was gone all night and Billy and Grace would talk about all sorts of things, especially the occult. Grace called herself a witch. He couldn’t see how because she didn’t even have a pointy hat. Plus, she was nice to him. How could she be a witch and be nice to him when his own father, a church deacon, knocked a back tooth out of his mother’s mouth for burning a roast. He would never tell his parents, but Grace was the person who gave him the book.

When his mother finally returned to the bathroom, she had completely changed her clothes and put on fresh makeup. She also had a white sheet which she wrapped around him.

“Pinch your nose, Billy. It will help stop the bleeding.” He did and fresh pain shot through him.

“Mama, it hurts!”

“OK, baby. Just try to press the ice against it as best you can.” As an afterthought, she added, “And try not to bleed on anything.”

She supported him as they walked down the stairs into the living room, making sure the sheet was always between her and her son. He took small comfort in the familiar surroundings: the Persian carpet, the hat rack and umbrella stand, and the oval stained glass of the front door. He carefully avoided his father’s picture on the mantel.

His mother opened the door and sunlight poured in on them. The Boston summer was hot and sticky, but the fresh air cleared Billy’s head a little. His father’s Continental was parked in the driveway, his mother’s Thunderbird by it.

“Let’s take your father’s car. You can bleed all over his seats.” She unlocked the car and got in the driver’s seat. Leaning over, she unlocked Billy’s door. Billy shifted the ice to his left hand and opened the door. As he bent forward to get in the car, a fresh wave of pain flooded his head. He was no stranger to pain; things like this had happened before. He got in the car, leaned his head back on the seat and closed his eyes. She started the car and backed it out of the driveway. As she drove to the hospital, she turned to Billy.

“Billy, sweetheart, what are you going to tell the doctor when he asks you what happened?”

Bill sighed and thought, here it comes.

“Baby, just tell him you fell down the stairs. People don’t need to know what really happened. OK, sweetheart?”

Billy turned to his mother and asked the question he had wondered about for years: “Why don’t we just leave, Mama? Why don’t we go far away where he can’t hurt us anymore? I hate him, Mama, I hate his rotten, stinking guts.”

His mother, alternating her eyes between him and the road, put her hand out and touched a blood-free spot on his arm.

“I know, baby. But, if we leave, who will support us? Your father makes a lot of money. How can we just walk away from that?”

“We could both work, Mama. I could get a paper route and you could be a secretary or something. Let’s just go, Mama.”

His mother’s voice raised a notch and her look became dark. “Billy, you’d make just about nothing from a paper route and I can’t type worth beans. I’d end up hooking.”

“What’s hooking, Mama?”

She was going to say “It’s what stupid fools who leave their meal tickets end up doing,” but she thought better of it and said, “Nothing, baby. It doesn’t mean a thing.”

Billy knew better but was in too much pain to worry about it. His mother, however, was going to ensure Billy did no real damage when talking to the doctor.

“So, Billy, what are you going to say?”

“I’m going to say my big idiot father tried to shove a book up my nose.”

“Billy?” she said softly.

He sighed, “OK. I fell down the stairs.”

His mother smiled. She still had a beautiful smile.

“That’s my boy, sweetheart,” and Billy thought, It’s too bad people can’t see the tooth he knocked out. He again closed his eyes and tried to find some special place he had read about like Arizona or Virginia City, Nevada, where big good-hearted Indians would take him into their teepees and teach him all the great stuff they knew how to do - stuff like tracking bears and pumas and making fire with two sticks; stuff like knowing what animals think, but maybe only full-blooded Indians can do that. He could be their little white friend and they would give him a pinto pony that would run faster than any big idiot white man father with a big idiot Bible who would hit you so hard that part of the word ‘holy’ showed on your cheek for fifteen minutes. And as his big idiot white man father was chasing him and getting farther behind because his pinto pony could run so fast, the big good-hearted Indians would call all the rattlesnakes together in one spot so his big idiot father would run right into them. And they would bite his father until he looked like a big porcupine fuzz ball with rattlesnakes all over him. His father would scream and twirl and pull at them but they wouldn’t let go because the Indians told them not to. They would tell the rattlesnakes that he was a big idiot white man father from back East where the cities are full of big idiot white man fathers who beat their wives and children and then act like big holy joe guys that never do anything wrong. And then his big idiot father would die with fang holes all over his white shirt and black trousers and all over his face and in his eyes and tongue and everywhere. And then the ants and coyotes and all the other cool animals could come and eat him until only his Bible was left and then his Indian friends could cause a big sand-storm to cover the Bible so no big idiot white man father could use it to beat any more kids.

Billy decided he liked that story and would write it down and put it with his other stories. Writing stories about great ways for his father to die was one of his favorite pastimes.

He opened his eyes and saw that they were in front of the hospital. His mother parked the car and, like she did every time she parked, took out her compact and checked her lipstick and hair. Then she turned to Billy. “Remember, baby, you fell down the stairs. OK?”

“Yeah, I fell down the stairs and hit myself in the exact same spot on every step.”

“Don’t make this any harder than it has to be,” she said sternly. “Besides, you were the one reading that book. You had to know what would happen if he found out. This is your fault, too.”

Billy supposed it was his fault and the beating was just the way big idiot fathers acted. He knew boys who said their fathers never hit them, only made them go to their rooms or took something away. He thought they were lying. And now his nose felt like toasted cat guts. And there was this stupid fly that kept buzzing around his face and he wanted that dead, too.

With great effort, Billy opened the door and got out of the car. He was hoping his mother would help him but she had already stepped up on the sidewalk and was pulling on her gloves. She put out one gloved hand and impatiently motioned for him to hurry. Billy went to her, melting ice and blood dripping down the white sheet. A man coming out of the hospital held the door for them. He emitted a standard-high-to-low whistle and said, “I’ll bet that hurts.” His eyes moved to Billy’s mother. “Anything I can do to help, little lady?” He knew his mother couldn’t help it. She was the kind of woman who dripped sex.

His mother’s eyes stayed straight ahead. “No, thanks.”

He tipped his straw fedora, eyes following her as she walked past and said, “Just thought I’d ask.”

Billy and his mother walked down the hospital corridor toward the front desk. He could hear the busy sounds of a big city hospital and the click-click of his mother’s high heels echoing like a harbinger. He was hurrying to keep up with her, his pain excruciating with each step. They reached the front counter and a heavyset lady in a white uniform looked at Billy and said, “Oh, dear. What happened?”

His mother was quick to respond. “He fell down the stairs. I think his nose is broken.”

The heavy-set lady pushed a clipboard and pen at her.

“Fill out this form and I’ll call for an orderly.”

His mother took the pen and inspected it for any leaks. Satisfied, she began to fill in the form. The heavyset lady picked up the telephone and asked for an orderly and wheelchair.

“Who’s his regular doctor?”

“Doctor Malik, and I was really hoping to see him. He’s been our family doctor for some time now.”

“I’ll call to see if he’s available.”

“Just tell him Mary Harold is here to see him.” His mother lowered her eyes and lightly pushed at the back of her hair.

The heavyset lady looked at his mother in an odd manner but made the call. After a short conversation, she hung up. “He’s very busy but he’ll meet you inside.”

By that time the orderly arrived with the wheelchair. Billy sat down and was wheeled toward to a room with a padded platform, metal cabinets, and a sink. Along the wall were glass jars full of bandages and charts showing people’s lungs, circulatory systems, hearts, muscles, and other medical peripheries.

“Have a seat, ma’am,” said the orderly. “The doctor will be here in just a second.” His mother sat down and crossed her ankles. As she folded her gloved hands and placed them on her white skirt, Dr. Malik came in.

“Well, the lovely Mrs. Harold and young Master William.” Dr. Malik always called Billy young Master William and Billy always smiled like it was funny because he was afraid Dr. Malik would give him shots or something to get back at him for not thinking his joke was funny.

Billy heard another high-low whistle as Dr. Malik leaned over for a closer look. Billy thought Dr. Malik was a pretty good doctor because he always had on a clean white doctor’s coat and a white shirt and striped tie. The coat always had Dr. Malik embroidered above a pocket containing two pens and a thermometer, and of course the ever present stethoscope with the parts that went into his ears wrapped around his neck and the cold part in his thermometer pocket. But the coolest thing was the round metal gadget attached to a black headband. The metal thing pointed upward and had a glass eye hole in the middle. Billy imagined that some great university put knowledge into the doctor’s head by radio waves. The round thing acted like an antenna and the eyepiece directed the knowledge into the doctor’s brain.

“Let me take a look, Billy.” Dr. Malik took the dripping ice towel and tossed it in the sink. He raised Billy’s chin for a better look at the nose.

“Well, it’s definitely broken. How did this happen?”

The mother, patting the back of her hair, said, “He fell down the stairs.”

“Take off your shirt and let me see the other bruises.”

The mother: “No other bruises, doctor. Only his nose.”

Dr. Malik looked back at Mrs. Harold for a full thirty seconds. His mother turned away and looked upset. Turning back to Billy, he said, “Billy has a lot of accidents, doesn’t he.” A statement rather than a question.

“You know how boys are,” said Mrs. Harold. “They’re wild and they have accidents.”

“Billy has had more accidents than any three boys I treat. Why do you suppose that is, Mrs. Harold?’

Billy’s mother looked down and patted her hair. “I really don’t know, Dr. Malik.”

“What do you say, Billy? Why do you think you have three times the accidents of other boys?”

“You mean other boys don’t have these kinds of accidents?

“Billy,” said the doctor, “just from what I can remember, you’ve had this broken nose, two concussions, one broken rib, and several stitches on the side of your head, all from falling down stairs, falling out of trees, and running in the house. You seem like a fairly coordinated boy to me. What’s going on?”

He looked at his mother. She was shaking her head no behind the doctor’s back. Billy decided to take a neutral path and shrugged.

“I see,” said the doctor, and started to probe the nose. Billy cried out in pain.

“This is really going to hurt. I’m going to give you a shot for pain.”

Billy hated shots but he knew he needed one now.

“OK,” he said. “Thank you.”

“My pleasure. And while the medicine is taking effect, your mother and I are going to have a talk in my office.” The doctor said the last sentence like he was a high school principal taking an unruly freshman into his office. After he administered the shot, he opened the door and held it for his mother. Her head was down and her hands were folded in front of her.

“Try to relax, Billy. Your mother and I will be back in about 20 minutes.”

Billy tried to lie down but his nose hurt too much. So he closed his eyes and tried to find a special place. He imagined cowboys had roped his father and were dragging him through the brush while they shot their six-shooters in the air and yelled cool cowboy yahoos. But the image faded as the thought of Dr. Malik helping him took precedence. He heard slightly raised voices coming from the doctor’s office and knew his mother and Dr. Malik were having ‘a discussion.’ Grown ups always call arguments discussions. His parents had them. They would always end up the same way - his mother would say that she wanted to discuss this in private and they would both go to the bedroom. After a while, his father would open the door humming “Onward Christian Soldiers” and his mother would be at her dresser mirror putting on fresh lipstick. When this happened, his mother always got her way.

Billy heard the words ‘victim’ and ‘prison’ coming from the doctor’s office and knew they were talking about his father going to prison. What a wonderful thing that would be: his big idiot father in prison dressed in gray and white striped pajamas and dragging around a big cannonball attached to his leg. He pictured his father with other big idiot men named “Spike” and “Lefty” with flattened noses and scars on their cheeks. He pictured his father strapped in the electric chair waiting to get the “juice,” hoping for a pardon from the Governor but, deep down inside his black heart, knowing none was coming. He saw his father begging his forgiveness before he “rode the lightning,” and Billy standing there with his mother and his new hero, Dr. Malik. Then he pictured playing catch in the front yard with the brand new baseball mitt Dr. Malik had given him, and his beautiful, sweet mother stepping out on the front porch and telling them dinner was ready while wiping her hands on her blue apron. Not white, never again white. He imagined them all sitting down to a wonderful meatloaf dinner, his favorite, and also the favorite of his new father. Dr. Malik was a great man; Meatloaf had to be his favorite meal.

He imagined the three of them driving through Nevada to meet big good-hearted Indians where his new father would exchange ancient medical secrets with wise old medicine men in furry hats with buffalo horns and then smoke a peace pipe. His mother should be willing to leave his big idiot father. Surely doctors made more money than his father. Billy thought Dr. Malik liked his mother; all men liked his mother, and his mother probably liked him. He saw them getting married in front of an Indian medicine lodge with totem poles and surrounded by happy, good-hearted red people in beautiful, soft buckskins, braided black hair and friendly smiles and strong hands that knew no evil holding the reins to a small pinto named “Doc.”

By the time the medication took full effect, the door opened and his mother came into the room. She appeared worried and only briefly looked at Billy. Her arms were folded before her and her shoulders were hunched forward so that her breasts seemed caught in a vice. She went to the far wall and leaned against a poster showing a human heart. She crossed her ankles and focused on her shoes. Billy couldn’t understand what was bothering her. Wasn’t Dr. Malik going to help them?

Dr. Malik came in the room and closed the door. He stepped to one of the metal cabinets and began gathering medical paraphernalia.

“Are you feeling the medicine yet, Billy?” Billy said he was so the doctor came to him with stuff in hand. “If you relax and let me do this, it will be over in about five minutes. You’re going to feel a lot of tugging and pulling, but it’s for your own good. It needs to be done. OK?”

Preparing himself for the worst, Billy said he was ready. He wrapped his hands around the edge of the bed and closed his eyes.

Through the haze of powerful painkiller, he felt tugging and pulling and grinding and gauze pushed up his nose. Then he heard tape ripping and felt the doctor’s thumbs pressing around his nose.

“OK,” said the doctor. “I think that will work.”

Billy opened his eyes and saw the doctor leaning right and left like a sculptor looking for flaws in a statue.

“Well, Billy,” he said. “You are going to be very sore for a few days and you’ll have two beeee-uuuu-tttt-iii-ful black eyes. But, in a couple of weeks you’ll be good as new. Your nose might be a little crooked but that adds character and the girls love it. Don’t they, Mrs. Harold?’

Billy looked at his mother. Her arms still held her breasts in the vice-grip and her back still crushed the paper heart.

“You bet, Dr. Malik, girls love it.” Billy no longer saw worry in his mother’s face. Instead, he saw determination. Billy’s mind filled with relief because he knew she had decided to send his big idiot father to prison with Spike and Lefty and the cannonball and he, his mother, and Dr, Malik would all be happy, maybe not in Nevada, that would be too good, but someplace. He knew that his mother would marry Dr. Malik and that he would get the new baseball mitt and Dr. Malik would teach him how to catch and hit and run.

“Come and look at yourself, Billy,” said the doctor, and helped Billy off the table.

He looked tentatively in the mirror. All the blood had been cleaned away and tons of gauge and bandages and tape were covering his character building, babe-attracting nose. His two beeee-uuuu-tttt-iii-ful black eyes were already metamorphasizing, and his whole face was swelling to stay-puffed marshmallow man proportions.

Billy looked at his mother. She looked tired and just plain worn out. Billy put his small hand on her folded arms. “Do OK Momb?”

After a few seconds, she brushed a strand of hair back from his eyes and said, “I’m OK, baby. Glad you’re better.” Without moving anything but her eyes, she looked at Dr. Malik.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Harold, I’m going to have to tell the police.”

There was a resounding ‘yesssssss’ in Billy’s mind but, as new fantasies began to articulate, he felt his mother’s hands on his shoulders forcing him to move toward the door.

“Wait outside, Billy. I need to talk to Dr. Malik alone.”

Billy imagined they were going to discuss strategic ways of arresting his father and readily agreed. He went through the door and sat down in the hall and listened. He heard low mumbling. Medical people dressed in white occasionally passed and smiled at him. He listened with all his might but couldn’t hear anything. After a few minutes, he thought he heard some moaning but couldn’t imagine what caused it. The door handle turned and Dr. Malik stepped out. His doctor coat was unbuttoned and he was smiling. He put both hands, fingers spread wide apart, on each side of his rib cage and took a deep breath, like he was inhaling wonderful, clean Nevada air. Dr. Malik looked down at Billy and winked.

“Take care of yourself, young Master William. See you in about ten days.” Then he turned and walked down the hall whistling what sounded like “Oh, Bury Me not on the Lone Prairie.”

Billy looked in the room and saw his mother in front of the sink. The water was running and she had wet her handkerchief and was rubbing a spot on her blouse. Her lipstick was smeared and her face looked flushed. And this was one of the few times he had seen her with her hair out of place. After a few more rubs, she held out the blouse so she could see it. Satisfied, she grabbed a paper Dixie cup by the sink, filling and drinking it three times in quick succession. Then she looked at herself in the mirror.

“Mamba?” said Billy.

“Come in and close the door. I have to fix myself before we leave.”

Billy came in and closed the door. “Whad happen? When is Ndanddy gooing to prisond?”

“Daddy’s not going to prison. Nothing is changing. Everything is all right.”

“But Ndanddy hurt bme. He alwaysd hurts bme, and he hurts you, doo. He dneeds do go do prison!” Billy was crushed. What was happening? He had never been more confused in his life. Tears began running down his face and catching on the strips of white medical tape.

His mother turned from the sink and knelt down until she was eye level with Billy. She grabbed his shoulders and shook them. Pain shot through his head.

“Don’t you understand? We need him! We need his money! He’s gone most of the time, anyway. Without him, you’d be pretending you were blind begging quarters and I’d be turning tricks in the red light district.”

Fear, pain, and confusion were writhing in his brain like three greedy, fat snakes fighting for position. “But…but…”

His mother’s voice turned into a controlled, whisper/yell. Her smeared lipstick made her look almost clownish. “For a smart kid, you’re dumber than dirt. Don’t you understand? I’d end up being a prostitute!”

A small light in his brain flickered. He knew what a prostitute was. It was a person who sold her body in exchange for something. He began to make the connection. His father wasn’t going to prison. Dr. Malik wasn’t going to the police; his mother had sold him out for money and a thunderbird and nice clothes. He knew she cared more about a nice house than what kind of abuse she and her son suffered at the hands of a maniac. He knew she was the thing she was trying to avoid. The Neverborne loved the Harold family. It was a home in which they felt comfortable. In a home like the Harold’s’, they only had to apply an occasional nudge to keep the family going in the right direction. As the Neverborne would say, the Harolds were very accepting of their nature.

Billy started spending more time with his sister, Grace. Neither his father nor his mother tried to stop him. Eventually, when he was about sixteen, after an additional concussion, a knocked-out tooth, and a scalded left hand, he completely moved out of his father’s house and in with his sister.

About the same time, his mother left her husband for a jazz musician hooked on heroin. She soon took up the habit and overdosed someplace around Chicago. She was thirty-eight years old and had already begun to lose her looks. Billy never bothered to find out where his mother was buried.

His father choked to death on a chicken bone about two months later. He willed all his money to Reverend Popejoy and the church, where an expensive funeral was held. Only three people came, the Reverend Popejoy and two ushers paid ten dollars each.