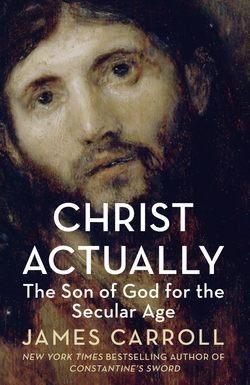

Читать книгу Christ Actually: The Son of God for the Secular Age - James Carroll, James Carroll - Страница 8

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Personal Jesus

Jesus Christ, with His divine understanding of every cranny of our human nature, understood that not all men were called to the religious life, that by far the vast majority were forced to live in the world, and, to a certain extent, for the world.

—James Joyce1

Where Is God?

The word “genocide” and I are exactly the same age. It is, perhaps, outrageously narcissistic of me to strike an autobiographical note in relation to the historic crime that, until then, had no name, yet the coincidence of timing somehow explains the obsessiveness of my Catholic preoccupation with the fate of Jews. So yes, “genocide” was coined the year I was born.2 It was the year that Los Alamos opened and the year Auschwitz became a true killing factory.3 The arc of the years since then defines the curve of the recognitions that shape this book. Awareness of the moral legacy of the Shoah and a felt sense of the radical contingency of life under the threat of the genocidal weapon have largely altered understandings of the human condition itself. The premise of this book is that those recognitions should therefore by now have equally changed the way Jesus Christ is thought of, by believers and nonbelievers alike. No such transformation has taken place. Yet Jesus has become a problem across the boundaries of faith and skepticism, the problem with which this book wrestles.

In my case, the change began with the paired witnesses Anne Frank and Elie Wiesel, whose testimonies overlapped. In 1960, I saw the filmed version of The Diary of a Young Girl as a high school senior at the U.S. Air Force base theater in Wiesbaden, Germany. Holocaust denial was a broad cultural motif everywhere, but in Germany proper, the murdered ones remained—as ghosts. While unacknowledged, the disappeared were nevertheless a felt presence. Our American enclave, for example, was a river town, an easy boat ride up the Rhine from Koblenz, which, we’d heard, was near Hinzert, one of the notorious “night and fog” concentration camps, part of the death network administered from Buchenwald. We sons and daughters of the American occupiers had whispered of such places, wondering what the Germans we encountered knew of them. Yet we were unable to actually imagine the horrors.

Suddenly, with the on-screen dramatization of the Frank family’s plight, the death camps were less unreal. The movie (like the play) ends with Anne’s sweet voice declaring, “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.” But I wondered. I left the movie theater feeling more shaken than I’d ever been by a film. I immediately read Anne Frank’s book, and felt implicated by it. Yes, she wrote those affirming words—but that was before she was taken off to Auschwitz. If she could have spoken from the grave—or the pit—what would she have said, actually? That question was the beginning of my inquiry.4

Anne’s was a real face for the horror, a girl with whom to identify. Many stateside Americans had this reaction to her, I knew, yet on Wiesbaden’s Biebricher Allee, where my Air Force family lived, I was all at once aware of Jews—former neighbors who were simply no longer there. Ghosts indeed. The film and book turned the abstraction of the “displaced persons,” as Jewish victims were still referred to, into a deeply felt anguish. On my street, Jews had been rounded up. Yet what I felt was less empathy than perplexity. I knew better than to assume that, had I been in Amsterdam, I myself would have been at risk in an annex room, like the Franks. No, I would not have been a victim. Then what? Sophocles again.

Elie Wiesel, whose Night I read only a year or two later, just as I was embarking on the religious life as a young seminarian, was another sufferer whose fate troubled me. The book describes the cramped dormitory where young Eliezer slept on the narrow upper berth of a bunk bed, a detail with which I unexpectedly identified, since my own childhood bed had been a shelflike upper bunk above the bed below. It seems wrong now to have made any comparison, yet I did. Under my bunk had been my brother Joe’s bed. Two years my senior, he had been stricken with childhood polio, and the disease, after numerous surgeries, left his legs twisted and shorn of muscle. Sometimes in the night, across the years that took me into adolescence, I would crane over the edge of my bunk to look down at my sleeping brother, expecting that he had kicked his blankets off. I would stare at his skeletal thighs and shinbones, bruised and gnarly with scar tissue. Under Eliezer, in that rancid death-camp dormitory, was not a disease-tortured brother, but his dying father. Eliezer, too, was powerless to help.

A shallow sort of empathy for Wiesel—even if my brother’s suffering went deep—yet I felt it. But that was as far as this recognition could take me. As a young seminarian anxious to prove my faith, I was troubled by the outrageous challenge to God around which Night organizes its narrative. Whatever my sympathy for Wiesel, it could not outweigh the scandal I took from his book’s climactic blasphemy—that, after such death as Auschwitz inflicted on the chosen people, God himself was dead.

In response to a fellow inmate’s called-out prayer at Auschwitz, Wiesel replied, “Blessed be God’s name? Why, but why would I bless Him? Every fiber in me rebelled. Because He caused thousands of children to burn in His mass graves? Because He kept six crematoria working day and night . . . ? How could I say to Him: Blessed be Thou, Almighty Master of the Universe, who chose us among all nations to be tortured day and night, to watch as our fathers, our mothers, our brothers end up in the furnaces?” Then Wiesel reports that a man asked, “Where is God? Where is He?”

In a well-known passage, Wiesel recounts an incident that occurred at Auschwitz. Prisoners were forced by the Nazi guards to stand before the gallows and watch as a child hung from a noose,

struggling between life and death, dying in slow agony under our eyes. And we had to look him full in the face. He was still alive when I passed in front of him. . . .

Behind me, I heard the same man asking:

“Where is God now?”

And I heard a voice within me answer him:

“Where is He? Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows.”5

For Wiesel, this moment epitomizes the death of God, an end of faith that equates, as negating revelation, with the theophany on Mount Sinai. Indeed, Auschwitz was the opposite of theophany—the manifestation of nothingness. Yet it transformed the imagination of many Jews, with history trumping religion as a defining note of identity—history perceived from the point of view of its climax in the Shoah.6

But I did not read the gallows passage as divine abandonment. For me, the vision evoked by Elie Wiesel at Auschwitz was a manifestation—and I would not see for years what a perversion this was—of the depth of God’s longing for human beings, God’s readiness to take their suffering as His own. Quite simply, to me, the young man whom Wiesel saw on the gallows was Jesus on the cross. His death was a replay of the great redeeming sacrifice. Jesus was the answer to suffering—to my brother’s, surely, but also to Anne’s and to Elie’s.

Like Christians of old, I was struck that the Jewish vision—Wiesel’s vision—entirely missed the meaning of Jesus’ death on the cross. In my own version of an ancient Christian surprise, I thought it obtuse of Wiesel—though I’d never have uttered such an insult—not to have recognized in his lynched campmate the agonized Christ, who alone redeems the evil of every abyss.

Enchantment

What one makes of Jesus depends, first, on how one sees the world. Though born near the middle of the twentieth century, I was initiated, like so many of my kind, into a way of thinking and believing that owed more to the Middle Ages than to modernity. I use myself as an example not because my case is special, but because it is not. My faith was grounded in a common teaching that shaped the views of most Catholics and many Christians. Fewer and fewer people in the contemporary age have experience of such a worldview, yet it was the decisive milieu in which every experience of Jesus could be had.

Religion, as I first embraced it, was less a realm apart than all of life, taken together from a certain perspective—a naive perspective, since it was not understood as such; not understood to be merely one of numerous possible vantage points. In my youth, all but unknown to me, premises of belief had supposedly been refuted decades or centuries before. Descartes, Darwin, Nietzsche, Freud, Marx, Sartre: hadn’t they all done their worst—or best—already?7 But the intact cogency of immigrant Catholicism in postwar America—and the same was true in other denominational settings—felt perennial, immune from any possible assault, including those said to have already occurred, whether from a profoundly threatening “science,” depth psychology, or from the erosions of “materialism.” In piety, liturgy, theology, and even metaphysics, midcentury Christian institutions were advancing conceptions of reality that had been untouched by the Enlightenment.

Intellectually, the parish in which our values and understandings were rooted was, well, parochial. But then, in our view, so was the much larger cosmos, consisting of a three-tiered geography, with Earth firmly bracketed by the up and down of heaven and hell, which were actual places to us. If space was constricted, so was time, with the now of this life set off from the then of afterlife. The realm of nature was set off from grace, the immanent from the transcendent. Yet all of these borders were porous. The natural world was under the influence of supernatural forces, which could interrupt history and alter the course of normal lives. Spiritual beings populated not just the cosmos but the air around us—saints, angels, archangels, spirits, and the devil, whose name was Lucifer. In grade school, I was instructed by the nuns to leave room in my chair for my guardian angel, ever beside me. For Catholics, the Blessed Virgin Mary was a vivid presence. Not so long before—in my mother’s lifetime—Mary had appeared to children like me, albeit Portuguese shepherds in the town of Fátima.8 Our Lady was capable of showing up anytime. Sun rays penetrating clouds to form a golden fan in the sky could itself seem an apparition. Was that her?

A Christian could participate in the economy of miracles by way of an earnest recitation of prayers. Specially blessed rosary beads were a feature of the Catholic parish. At Mass, the women absently carried them, wrapped around fists or dangling from fingers, the way office workers now display credentials on clips or chains. Sometimes, watching television from the living room floor, I would glance back at my mother and see her lips moving, only to glimpse the beads in her lap. I recall thinking that they slipped through her thumb and forefinger the way cartridges moved into the machine guns of war movies. A woman who stifled expressions of distress, Mom showed it mainly in her compulsions of devotion. Quiet supplication was her constant mode, and a wealth of aids was available in the form of relics, which she handled like pieces on a game board—the little gold pendants and boxes that enshrined bits of bone or cloth, tokens of the saints who had already overcome all woes and worries. A game board, but more than a game was in play. Relics had one function in our house, as I understood whenever I saw her touch them to my brother’s withered legs. The prize of her collection was a crystal vial of holy water said to have been collected from the stream at Lourdes.9 At night, she sprinkled Joe’s bed before kissing his forehead. I was entranced by, and wholly convinced of, the efficacy of such rituals. It did not occur to me to wonder why my brother’s ordeal was never lessened, or why his legs were never made whole.

All of this defines an enchanted world that was not recognized as such, perhaps, until it was declared “disenchanted” by social scientists.10 As I came of age, eventually learning in school to name and date Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, and Darwin (although not Marx, Freud, or Sartre), Benedictine monks and Jesuits instructed me and my mates on the compatibility of science and faith (Copernicus was a priest!), helping us to avoid the common notion that descent from monkeys, say, undercuts the creed. My teachers, that is, protected the fragile middle ground between atheism and fundamentalism, the middle ground where most American Christians lived at the time, although fewer do so now. But the clerics taught these lessons with an imperative vehemence that showed that religion had things to fear in the secular progression, as Charles Taylor defines it, from living in a “cosmos” that crackles with intimations of the transcendent to being included in a “universe,” which understands itself wholly in its own terms. Reformation, Renaissance, Enlightenment, science, deism, skepticism, and “a kind of galloping pluralism on the spiritual plane”11 left traditional religion on the defensive. And instead of inviting questions, a gingerly Christian education in modern ideas discouraged them. Evolution was real, but so were Adam and Eve. Earth revolved around the sun, but it remained, nevertheless, the center of God’s creation. Man was its pinnacle. Natural law reflected the Creator’s absolute presence in creation, but the laws of nature could be violated by the miracle-working Creator at will. The moral order was arranged in a “hierarchy of being” that was presided over by God, yet leveling principles of democracy were, at least in our America, to be revered. There were as many contradictions in this new cosmology as there were stars in the night sky—and they were taken in stride by chalking them up to “mystery.” The night sky’s galaxies seemed infinite, but—a priori—could not be. Only God was infinite.

And because of the sin of Adam, God was at infinite remove. Our human forebears had abused their gift of free will, and that was what accounted for the suffering that was part of every life. I saw this early. If I could not actually put myself in the place of the first two biblical ancestors who’d started the unbroken chain of human sorrow, I readily attached their bequeathed misery to my Irish grandparents. I sensed the weighted legacy I had from them—the measure of what I knew to call original sin, which might have been the first large idea I made my own. My mother’s mother carried the wound of the Irish famine in her sad eyes, and my father’s father displayed it in his taste for alcohol, which, early on, I recognized in the sour odor of his breath. The “ould sod” was the Eden from which my family had been sent into exile. When, at the end of every rosary recitation, we prayed as “poor banished children of Eve,”12 I thought of green Ireland.

Punishment was a feature of the world first presented to me. As my sense of time began not with the first day of creation, but with the eaten apple, my religion began in the idea of hell. I often lay awake at night, in that narrow bunk above my scar-ridden brother, parsing definitions of the Baltimore Catechism, which made clear that “the damned will suffer in both mind and body, because both mind and body had a share in their sins.” The body’s suffering would consist in being “tortured in all its members and senses.” Fire was the given image. Nausea choked me during those dark-night bouts of anguish, as I struggled to get my brain around “infinite pain, infinitely felt—forever.” Plunging into that idea—down, down, down—was the nightmare that, when I woke just before hitting bottom, made me know why they called the sin of Adam the “Fall.” My first luminous sensation of transcendence, that is, was the horror of eternal damnation. Obsessed with hellfire, I once held my hand over a candle to test the pain. I managed not to cry out, but the blister became infected.

In fact, I was a good boy, rarely punished by my parents. But I dreaded punishment all the more for that—which, no doubt, helped me to be good. The most dramatically locating experience of my childhood was initiation into the Sacrament of Penance: Confession. At age seven or so, I grasped that the confessional booth was the judgment seat of God, which was why the priest, God’s representative, was seated, while we the penitents would kneel. First Confession was prerequisite to First Communion, scheduled for the next day. Ahead of the momentous rite of passage, I was instructed in the rubrics of self-scrutiny, which presented me with what I understand now as my first conscious moral dilemma. I was assured by the nuns that I was guilty of sins and that, in the darkened booth of the confessional, I was to explicitly admit them—not so much to the priest but to God, who was in there, listening. Of course, God already knew what my sins were.

My dilemma was immediate, and simple. I could not think of any “sins” I had committed. The examples offered in the preparation sessions—anger, lying, stealing, taking God’s name in vain, failing to say prayers—defined actions and attitudes to which I had no known connection. Not that I assumed innocence. I was convinced that I had committed sins, but without knowing what my sins were, which was surely another lapse. So, on my knees in the darkened booth, staring at the profile of the priest, whose aroma reminded me of my grandfather, I confessed to neglecting my prayers, although, to my knowledge, I had not. I said I had disobeyed my parents, which I would never have done. I admitted having had bad thoughts, with no clue as to what such thoughts could be. In the recitation of my scrupulously memorized Act of Contrition, I solemnly declared to God that I was sorry for my sins less because I “dreaded the fires of hell” than because they offended Him, who “art” all good—and that was not true, either.13 Avoiding the fires of hell was absolutely the point of what I was doing. No sooner, having carefully made the sign of the cross in sync with the priest’s words of absolution, did I push out through the velvet curtain into the shadowy church than it hit me that, in my first Confession itself, I had lied. Now I had a sin—a mortal one. And God knew it! More than that, it was God to whom I had been untruthful! As I knelt at the Communion rail to say my Hail Mary, I stifled sobs, which the nuns took as a signal of my piety—a further deception. My emotion was moral panic, pure and simple, a draft of the poison of scrupulous self-loathing that can ambush me to this day.

I know now that this was not the intended faith of the Bible, yet it came to me with biblical potency. Oddly, perhaps, religion gave me my first taste of despair—for, despite my youth and, yes, innocence, despair was the distilled essence of all these feelings. I acknowledge that I am describing here the initiation of a susceptible and vulnerable child into fear and guilt—yet this is a system of inculcation many Christians would recognize, the mechanism of what’s called “atonement.” As a system of inculcation, it strikes me now as ingenious. In the melodrama of my own recruitment into the Catholicism of my parents and grandparents was recapitulated the central dynamic of the faith—not as it began, perhaps, but as it unfolded across the centuries: Jesus as the answer to an impossible question.

I retraced the well-trod route: Religion made me aware of God, but God was forbidding and judging. God presided over hell, which was far more vivid to me than heaven, where, in any case, the sovereign was not God but God’s Blessed Mother, Regina Coeli. God’s omniscience boiled down to His capacity to see through to the core of my unworthiness. So why shouldn’t I have viscerally grasped the urgent need of some intermediary, someone to take my side against God and keep me safe? Not safe from Lucifer, mind you, nor from my own concupiscence, which was surely the first four-syllable word I learned, but from the Creator of the universe Himself. For such salvation to take, it had to be offered by one who could counter an enemy God’s threat with equally stout protection, a balancing of the scale, which required nothing less than a friend God. And wasn’t that precisely the offer coming, wondrously, from Jesus Christ, the Son of God? Jesus alone could get God the Father to change His mind about me, from damnation to redemption. So, of course, I accepted at once. I took to Jesus as one drowning takes to air.14

God’s Legs

In the beginning, Jesus was a boy with whom to identify. A favored picture book showed him by Saint Joseph’s side in the tidy carpentry shop attached to the modest house in Nazareth. Jesus, looking to be ten or eleven, used his foster father’s carving tools to fashion a little bird. He was a boy like me, until . . . until . . . he breathed on the model he had made, and it came instantly to life. The bird’s wings fluttered, and all at once it lifted off Jesus’ hand and flew away. The boy who seemed like me was God the Creator.15

That Jesus grew up and accomplished the purpose of his life by suffering, as my brother, Joe, was suffering, sealed Jesus’ significance. Joe is central here because, of course, his condition was the content of my guilt. I was at the mercy of dread that my sin, whatever it was, had caused his polio. The punishment due to me had been cruelly deflected onto him. My healthy legs were the precondition of the scarred blight of Joe’s.

The starting point of the reflection we pursue here was Elie Wiesel’s question in the face of wretched suffering, “Where is God?” Without meaning in any way to equate my bunk bed with Wiesel’s, I am accounting for the answer that was given to me. When, as an altar boy, I knelt before the crucifix at St. Mary’s Church, it was the battered legs of Jesus that transfixed me. God had legs like Joe’s. That the monsignor refused to let Joe become an altar boy because he had the limping gait that went with such legs was my first lesson in the difference between the all-loving Lord and the Church authorities whose kindness is self-servingly selective. Somehow it had become crystal clear to me that Jesus, as God, could readily have avoided the tortured fate of crucifixion, but he’d freely taken it on—here was the nugget of my first belief—for the sake of my brother, Joe. I loved my brother, and so did Jesus. When I looked down from the top bunk, I saw one for whom God’s love was absolute—absolute to the point of the cross. That love established my first sense of the moral order of the cosmos, just as the stars in the sky bespoke its physical order, and as the sure presence of a guardian angel beside me did the spiritual order. The moral order is love. Love embraced Joe. And me. Where is God? God is here, in the bunk bed with us, as love.

But love is tied to suffering. In the liturgical cycle that was the main calendar of our parish, Good Friday defined the year, just as that holy day’s crucifix-centered suffering defined the depth of the Jesus God’s love for us. As an altar boy, I was regularly present for the solemn veneration of the cross, the stripping of the altar, the dousing of the sanctuary lamp, the clothing of every surface with black. The Gospel account of the Lord’s Passion and Death was the first true dramatic narrative that I made my own—as an Athenian boy, perhaps, would have internalized the journey of Ulysses.

As the entire dynamic of a faith that transforms God from enemy to friend had implicitly rooted me in the so-called penal atonement, so the fate of the loving Son as an appeasement of the judging Father brought me, also implicitly, into a world of contempt for Jews. To indict Jews as the instrument of Christ’s suffering does not go far enough. Jews made that suffering necessary in the first place. Following the sure logic of the salvation Jesus offered, I viscerally grasped why those who put him on the cross—notwithstanding that it was a Roman execution device—had to be the Jews. The matter was simplicity itself, since the enemy God from whom Jesus had come to save us was the Jewish God, also known as the God of the Old Testament.

As the merciful, loving God of the New Testament—the “Abba” of Jesus—began to vanquish the damning, vengeful, lawgiver God of Moses, the Jews were naturally determined to defend their brutal deity. If that meant killing the carpenter’s son from Nazareth, the Jewish God willed it. Why else were His high priests in the forefront of the crucifixion? But Jesus triumphed. The God who was Law became Love, with an attitude of boundless mercy for all—except, perhaps, for the Jews who had killed His Son. The Savior saved those of us who followed him from the very ones who had killed him—Jews. Because he did, they could not kill us. Although we never forgot that, if they ever could, they would. Jews were the enemy, period.

So even the religious imagination of a normal Christian child was shot through with the buried fury of anti-Judaism. In my case, as noted, it was through openings crafted by Anne Frank and Elie Wiesel that these overheated currents first broke the surface of awareness. Ultimately, revelations tied to the Holocaust burst forth as the steaming geysers of a late-twentieth-century moral accounting. Because of accidents of circumstance, I myself had no choice but to take the temperature of this fever—hatred as an illness in the religion of love.

I came of age as a Catholic priest. To my surprise, I was initially required by my Church to continue the reckoning I’d begun with Anne Frank. During my seminary training, Christian theology reversed itself in the matter of the “Christ killer” slander, a change sparked just then by the Second Vatican Council, already referred to. The council was itself an overdue attempt to respond to what had been laid bare by the Holocaust.16 Christian thinkers began to contemplate the possibility that Jews had not been wrong to reject the Gospel, given the ways in which it was presented to them. The Christian doctrine that the covenant God made with Israel had been “superseded” was repudiated. Christian preachers of my generation were instructed in new ways of reading Gospel texts that had previously demonized “the Jews.” And a new wave of “historical Jesus” scholarship was launched, in part as an effort to purge Christian attitudes of an anti-Judaism that inevitably insulted Jesus himself, who—surprise!—was Jewish.

When I was a college chaplain in the late 1960s and early 1970s, my priesthood took root in the call to bring Jesus alive for young people, which brought him alive for me. As civil rights, peace, and social justice issues defined my ministry, I found myself emphasizing a memory of Jesus as a resister of unjust social structures and the empire that protected them. During the years of the Vietnam War, haunted by the record of a Church prostrate before the Nazi onslaught, priests like me joined the antiwar movement, however timidly. Silence in the face of a criminal war was not an option. My piety was redefined around the image of Jesus as a man of nonviolence. Indeed, far more was at stake for me than mere piety. Because I was raised to obey, not to rebel, and because my father was himself a man of war—an Air Force general with a key role in the U.S. bombing campaign that would kill more than a million Vietnamese—only the counterweight of a divine sanction could justify my open rejection of Dad’s worldview.

The climax of that rejection came in a midnight jail cell in Washington, D.C., where, with other religiously motivated antiwar protesters, I joined in the singing of verses from Handel’s Messiah. I felt fully and unexpectedly released when we came to Isaiah’s resounding litany, “called Wonderful, Counselor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace.”17 That Jesus was essential to this rite of passage, enabling me to claim my adult identity as a man, separating from my father, sealed my bond with him forever.

As the Catholic hierarchy began to roll back the liberalizing innovations of Vatican II, reimposing restrictions on women and reinvigorating old Catholic rejections of modern thought, I came more than ever to see in Jesus’ conflict with Jewish high priests, scribes, and Pharisees a model of anti-establishment dissent—that Che Guevara figure. I did not realize that I was resuscitating an anti-Jewish motif. As a left-wing priest, I would be “marginal” to the reactionary Church and to war-making America the way Jesus was marginal to the Judaism of his day.18 To see dissent as righteous, in our oppositional culture—also known as “counterculture”—one simply had to reject orthodoxy. The liberation theology that my kind embraced began, in its Gospel template, as liberation from an implicitly Jewish power structure. The Jews.

After five tumultuous years, I left the priesthood to claim a more spacious Christian faith, which freed me to begin a profound recasting of the meaning of Jesus Christ. Only as a former priest was I free to question the assumptions—going far deeper than ancient “Christ killer” slanders—that perpetuate, even in this ecumenical age, anti-Jewish stereotypes. Again and again, I had to confront the ways in which my own attitudes toward Jesus were stubbornly anti-Jewish. As a person in the pew, also, I regularly heard the negative-positive pairing of Old Testament against the New Testament, and the tone-deaf sermons that assumed the war between Jesus and “the Jews.” I still hear such preaching at least once a month.

I staked my future on a writerly conscience, but I never abandoned my first religious insight—about God and suffering. It meant everything to me that the entire religious tradition of which I was still a part began with God’s coming to Moses not because God had seen the sin of the people, but because He’d seen their suffering: “I have seen the affliction of my people who are in Egypt,” He told Moses, “and have heard their cry because of their taskmasters; I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them.”19 Yet it took me decades of work on the sly mechanisms of the anti-Semitic imagination—including two books detailing the history of Christian contempt for Jews20—to reverse my primal identification of the gaunt-eyed Jews at barbed wire with the flayed and battered body of my Lord. Having put Auschwitz at the center of my work, I found it necessary, instead, to look at Jesus with the death camp as a lens—the opposite of my innate urge to see Auschwitz through the redeeming frame of Jesus’ self-sacrifice. At last, I shared the recognition that Dietrich Bonhoeffer had come to in a Gestapo prison; I could see the point that Elie Wiesel had made before the Auschwitz gallows: If Jesus had been hanged there, it would not have been as the atoning Son of God, but as another Jewish victim. Period. If there is to be Christian reckoning, it must begin there.

The Search for Meaning

I have outgrown my childish faith. About time, for a man my age. I’ve left behind naive assumptions about reality irreparably divided between the material world and a separate spiritual world, the bifurcated realms of nature and grace, this life and afterlife. I don’t think that the Enlightenment’s closed system of mechanistic cause and consequence more faithfully renders reality than the spirit-filled world of miracles, but neither do I expect divine interference in history. I hold the faith not because religion can prove its claims for God, but because those claims can make a cosmos that includes self-knowing creatures more intelligible, not less. Proof is not the key; it is irrelevant.

That we know ourselves, and know that we do—there’s the opening to mature belief. One can move through it even in an era when the creation is understood as the infinitely expanding cosmos, rushing madly away from an unknown center, with humanity ever more marginal, insignificant, and puny. Yet we are the puny creatures who know, who think, and who love. We will return to this idea. The point here is that, as humans go endlessly in search of meaning, we also dare to ask what is the meaning of meaning?

“In the beginning was Meaning, and Meaning was with God, and Meaning was God. . . . Meaning became one of us.” That eccentric translation of the opening verse of the Gospel of John—traditionally rendered as “In the beginning was the Word . . .”—points, in an age when the quest for “meaning” has replaced the hope for “salvation,” to a new sense of the relevance of the idea of God, drawing on a particular tradition of Western culture that makes God present.21 A tradition named for Jesus Christ, who, whatever else can be said of him, was a man whose meaning captured what is essential to the meaning of every human fate. And he did this as a Jew—only a Jew, a Jew to the end.

Therefore, the most important way in which I have left behind the childish things of my religion has to do with the Jewish people, whose history remains the key to a plausible and morally responsible faith. I repudiate the hatred of Jews that courses through Christian understandings of Jesus like veins of mineral impurities through marble. “Impurity” in stone hardly defines the wickedness of this history, yet it does suggest the actual pervasiveness of the mentality, belonging, as we have already seen, as much to me as to my tradition. I have no right to judge the hatred of Jews from a place on the moral high horse.

It helps to know how that hatred perverted the story of Jesus, starting with the very human conditions within which the New Testament faith first grew, coming eventually to the apocalyptic climax of 1945, and continuing to the Christian reckoning that has been occurring since then. The long, tragic drama includes unpredicted turns of history more than any will of God. And it shows that, just as the first intimate friends of Jesus betrayed him at his hour of greatest need—all fleeing, except the women—so, too, were the second and third generations of Jesus people treasonous when, however inadvertently, they remembered him in a way that set him against his own people.

Even before that, was there perhaps betrayal when, in the phrase the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus uses of them, “those who first loved him and could not let go of their affection for him”22 stopped proclaiming the Kingdom of God, as Jesus had, and began instead to proclaim Jesus himself as Lord? The primal texts are complex when it comes to this question, as we will see. But what Jesus never did—put himself in the place of God—the Church did, making his humanity deeply problematic. Twenty centuries later, the most fateful consequence of that twist in the story was made brutally clear, for Jesus’ Jewishness had thereby been made problematic, too.

There’s the surprise. The deep past is far more present with us than we think—not only a past that is defined by the figure of Jesus, but a past that took its shape from forces with which, despite seeming dissimilar at first, we are in fact quite familiar. The quest for meaning is never finished. It is open-ended. It is shaped by the imperfections of human perception. Seeking the truth about Jesus can lead to mistakes about Jesus. Our most well-intended efforts are marked by a propensity for error and—most dramatically, as this story will show—by impulses to run from danger. Equally, on the positive side, these efforts are marked by our enduring capacity as humans to surpass ourselves. Once we have tasted the delight of meaning discovered or invented, our thirst will not be quenched. A personal Jesus is never enough. As much as he beckons, so he withdraws at our approach. Such contingencies, for better and worse, drove the faith forward into history, and still do.

Christ actually was like us in all of this, yet for him the lasting anguish would have been, perhaps, in how his elevation as meaning itself, from Word of God to “God from God,”23 ultimately drew attention away from the only One to whom he ever wanted to point. That was his Abba, the God of Love who—this must be emphasized—always was and always will be neither an “Old Testament God” nor a “New Testament God,” but the God of the Jews, pure and simple.