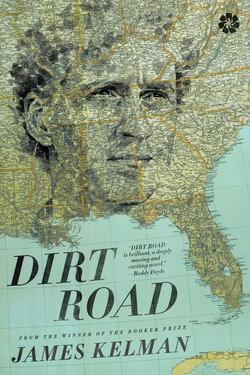

Читать книгу Dirt Road - James Kelman - Страница 9

ОглавлениеIt was half five in the morning when his father wakened him. Murdo lay in bed an extra few minutes. There was a lot to think about. But that was all, thinking; he finished the packing yesterday. Soon he was up and downstairs for breakfast. Dad had eaten his and was doing the last-minute check to electric switches and gas taps, water taps and window snibs. In a couple of hours’ time people would be going to school. Murdo and his father were going to America.

Then they were off, walking down over the hill and on down to the ferry terminal, Dad pulling his suitcase, Murdo a step behind, rucksack on his shoulders. Dad had wanted him to bring a suitcase too but what a nightmare that would have been.

It was a good morning, fresh and new-feeling. An old neighbour and his dog were returning from the newsagent. He saw their luggage and was ready to stop for a chat. He told long stories and Murdo quite liked listening but just now there was no time. Murdo gave him a wave. Dad had barely noticed the old guy anyway. Father and son carried on down to the pier.

A guy Murdo knew was by the entrance to the ferry terminal. His young brother had been in Murdo’s class at school. The guy was working and there was no time to blether. The early morning ferries were busy. People crossed to the mainland on a daily basis to get to their work. Murdo’s father was one of those and must have recognised a couple of the passengers but he didnt nod to any of them, not that Murdo saw. Dad didnt talk much anyway. As soon as they sat down he brought out his book and began reading. Murdo sat thinking about stuff. If anybody had asked what about he wouldnt have known. All sorts and everything. Soon he got up to go outside. I’m just going out a minute, he said.

Dad nodded and continued reading.

Murdo had made this ferry crossing a million times but it was still enjoyable. He leaned on the barrier seeing down towards the island of Cumbrae. Next thing they would be flying over it. But they would hardly see it because it came so close on the take-off. Murdo had only been on a plane once before, for a holiday in Spain. So that was twice, there and back. All he remembered was a happy time. What made it so happy? He stopped the thought. But it was not even a thought. The image from a photograph. His mother and sister were there.

When Murdo thought of “his family” that was what he thought about. The family was four and not just him and Dad. Mum died of cancer at the end of spring. This followed the death of Eilidh, his sister, seven years earlier from the same disease, if cancer is a “disease.” He could not think of cancers like that because the way they hit people. One minute they were fine but the next they were struck down. More like a bullet from a gun was how he saw it: you walk along the street one minute and the next you are lying there on a hospital bed, curtains drawn, nothing to be done and nobody to help. The cancer his mother and sister suffered struck through the female line and ended in death. Males cannot help. All they can do is be there and be supportive. What else? Nothing, there is nothing.

That was weird, not being able to do anything, thinking of doctors and all medical science yet nothing. Murdo found that difficult. His Dad must have too. Murdo didnt know. It was not something they spoke about.

He was standing by the rail, enjoying the sea-spray, that freshness. Nobody else was there. Too blowy. Either they were inside where Dad was or else had stayed in their cars. Boats were better than planes. Even wee ones. If ever he made money he would buy one. Even before a car he wanted a boat. With a boat ye could sail anywhere. Depending on the engine, or maybe the sails. Guys he knew had boats; their dads anyway, or uncles. It would have been great. His father didnt bother. When ye take one back and forwards to yer work every morning ye dont want to be doing it in yer spare time. As if traveling on a ferry was the same as sailing a boat. It was the kind of daft thing Dad said, because he couldnt be bothered talking seriously about stuff.

Then the guy was there whose young brother was in Murdo’s class at school. He already knew they were headed for America and was wanting to know how long they were away. Murdo said, Two weeks I think.

Ye think! The guy chuckled.

Well maybe it’s two and a half. Murdo grinned.

The guy clapped him on the shoulder, still chuckling, took a last couple of puffs of his fag and flicked it overboard. Murdo knew it sounded daft, not knowing how long they were away for but Dad hadnt told him. Or had he? Maybe he had. Sometimes Dad said stuff and he didnt take it in. He would have had to ask to know for sure, and he didnt like asking. One question at a time.

The truth is he didnt care how long he was going away. Forever would have suited him. It didnt matter it was America. America was good but wherever. Things closed in. It was not Dad’s fault, just life. Murdo was nine when his sister died. With Mum he was sixteen. People die and you cannot do a thing. All the cannots; cannot cannot. Nobody nothing nothing nobody. Cannot cannot nothings for nobody. The person is just nothing. You cannot help. Nobody can. People say how it eats inside you. It is true. That was it with Mum. Every moment of the day thinking about it from first waking in the morning till last thing at night: is she asleep or awake, and what do her eyes look like, is she seeing stuff or are they that other way, just nothing, her eyes just nothing.

People say about getting away. Yes to that. It was the best thing ever could have happened.

The ferry was set to dock. Dad was waiting for him. He shrugged when he got there. It was a particular shrug. It meant Murdo should have been there two minutes ago and should watch it in future. This was a bit daft. Ye could miss getting on a boat but not getting off. How could ye miss getting off? The ferry docked and that was that. Dad was like this when it came to stuff. Maybe he thought they would miss the train. But how could they miss the train? It was there to connect with the ferry. If for some reason it was postponed they would just jump a bus. Dad had left time for emergencies.

They walked fast with the other passengers. Some raced to get the best seats on the train. On board Dad said,You got everything?

Murdo shrugged. Yeah. He was unsure what Dad meant. Dad had the passports, the visas, the tickets; everything, Dad had everything. All Murdo had was himself and his money which was just about nothing. He went in for his phone, the pocket where usually he kept it. It wasnt there. He tried other places. Maybe it was in the rucksack: he never kept it in the rucksack.

Dad was back reading his book. Dad read books. The train started moving and the ticket-collector was coming. Murdo gazed out the window, then tried his pockets again. The idea of leaving it behind! What a nightmare. Surely not? How could he have? He couldnt. Yes he could.

Dad was watching him. Alright Murdo?

Yeah Dad.

Dad nodded, turned a page in his book. Murdo waited until the ticket-collector had passed along the train then unzipped the compartments in his rucksack one by one. Still nothing. He really didnt have it. He actually didnt have it.

Dad was watching him again. Murdo said, Dad I’ve left my phone. I’ve left it. I had it on the kitchen counter ready to take. I dont know, I just, I forgot to lift it.

Dad said, Have ye checked all yer pockets?

I’ll check them again.

He checked all of his pockets again and every part of the rucksack but the phone wasnt there. He really had left it. Murdo said, Dad I’m sorry. I’m really sorry.

Dad nodded. A bit of peace without it I suppose.

Murdo sighed, zipped up the rucksack and stared out the window. That was him now, nothing. What did he have? Nothing. This was the first stage of the journey then there were all the rest.

The flight to Amsterdam was an hour and forty-five minutes. Then twelve hours to America! Twelve hours! Once the doors closed that was you; locked in, barred and bolted. And nothing except some stupid movie. Or else whatever, like if they had some kind of in-house sound system, maybe iTunes or something. Imagine a pill. Ye went on board and they gave you it to swallow. Next thing ye were getting off. They could hit ye on the head with a hammer. That was you out until ye got there. Memphis was the place they were landing. Although dont speak too soon. People said that. They touched their head for luck. Touch wood so touch yer head, as in a joke; which was stupid when ye thought about it. Yer head is not wood. So dont touch it for serious things. People say that too. If ye do need good luck never ever touch yer head. Not even as a joke. Murdo understood this way of thinking. Never say a thing until it is done. Dont take the fates in vain, they dont like it. Mess about with luck and it might turn nasty. Amsterdam to Memphis was a very long way. How far? Murdo was not quite sure. The lucky thing was his rucksack, it was light enough to carry on board.

Imagine the whole Atlantic Ocean. Having to swim it. Thousands of miles of water. Although if the plane crashed ye would be dead in five or ten minutes. He heard that someplace. Unless the pilot managed to land at a good angle so the plane could skite along like how a sea-plane lands on the water, and if ye had enough time ye would grab the rubber dinghy. The pilot signaling the Mayday emergency. Other boats coming to the rescue. Fishing boats and cruise-liners; all sorts; even yachts. Some yachts sailed long distances. It depended whereabouts they crashed although the middle of the ocean would be hopeless. Then escaping the plane, who was sitting beside you? What if it was a big fat guy? Imagine it was an old lady, or a wee kid or a baby, they went first and might need help unless if the baby’s parents were there they would be the rescuers. So it was the old lady left behind, and other old people, depending how strong they were, and the ones that were disabled and needed pushchairs. Then all the luggage in the hold, what would happen to it? The luggage would all be lost. Bobbing about on the sea. People would want to save their own stuff but there would be no room on the dinghies.

Water can be calm this time of year. It was maybe a good time for flying. Murdo liked the water at night, seeing the waves glint. Then if it was a night where ye could see all the stars. Olden-day sailors used the sun and stars to guide their boat. There was good stuff online about it. The joke in school: please sir if Mercury is in Venus is it a bad day for geometry? Although things like stars and luck irritated Dad. Especially luck. Dad didnt believe in luck. He was wrong.

Ye cannot control yer health. If something goes wrong and has nothing to do with you, what else is it but luck? Genes is luck. If it is there in yer genes then that is you. People said it was “meant.” That annoyed Murdo never mind Dad. It was like God decreed. God would never decree somebody dying. It was complete nonsense. What about the ones that didnt die? What was decreed for them? Were the ones that died only put here for the sake of the ones that didnt die? What was decreed for them? Was Dad only put here to marry Mum then for their daughter to die then his wife as well? Then if the plane crashed and Murdo drowned but Dad didnt. So everything was for Dad, and God was decreeing it all for him? Is this why Murdo was on an airplane, so he would die in the crash? What about the pilot and the other passengers? Did they all die for the benefit of Dad? It was total nuts.

In a movie there was a woman in a crowded airport kept seeing this figure and it was a ghost flitting here and there. The woman knew the ghost was “for her” and was looking to find it. The ghost kept one pace ahead and the woman could never reach it till then she missed the plane. The plane crashed and was never seen again. So the ghost there was good, more like a friendly spirit. Murdo didnt believe in ghosts but spirits were different; spirit worlds, “presences.” There could be a presence. He used to get a feeling when he was doing something like eating a nectarine. It was Eilidh, his sister. She loved nectarines.

***

At the Amsterdam terminal nobody in the waiting area for Memphis was from the Glasgow plane. Not one Scottish voice apart from him and Dad. Different people from all different parts of the world. Four Muslim girls too. Probably to do with school or their religion. Religions have different things about them. Maybe this was part of theirs. They wouldnt have noticed Murdo.

Although why not? People get noticed and he was a person. Imagine speaking their language. One of them could have asked a question and nobody knew what she was saying except him. Maybe they were getting hassle to do with being Muslim. And he would say something and she would be amazed and happy at the idea of this guy knowing.

In Memphis airport they kept close together. Long lines of people queued at the place for visas and passports. The lines twisted round to make use of the floor space. Cops or maybe soldiers walked up and down with guns and sticks in holsters. Some had rifle weapons cradled in their arms.

Dad touched Murdo on the elbow, thinking he was staring but he wasnt, he was looking. Everybody looks. Ye see something new and so ye look. People do that. Why not? Otherwise they wouldnt have eyes, they wouldnt see where they were going. Who to talk to, they wouldnt know. Some people were kept to one side, looking about or staring at the floor; children, everybody.

Then a security man poked Dad on the arm. Dad was annoyed. The guy knew he was but didnt care, he just gave him a look as if “hurry up hurry up.”

In the carousel section the luggage hadnt arrived but the conveyor belt was moving. Murdo went in for his phone automatically. This time he didnt try all the pockets. That was that, he didnt have it. Dad should have had his own phone anyway instead of relying on Murdo. He said he wasnt, he said he was just taking a break from using phones. Fair enough for texting and making calls but for like checking information, if ye couldnt go online, it was just a problem.

People were shoving forward to get a better view of the luggage. Kids too and it was a bit dangerous. Dad kept watching in case one of the kids fell or got their hand stuck someplace.

Outside the restricted access area friends and relatives gathered; some holding cards with names written. Maybe somebody was waiting for them! Who could it be? Nobody. Uncle John and his wife were hundreds of miles away. There was an airport in a town near where they lived but only for domestic flights. They could have made a connection but it cost too much money. Dad had other relations in America but whereabouts nobody knew, only that they were there.

Signs and directions for taxis, connecting flights, buses, hire cars and trains. A big queue at the information desk. Dad left Murdo to guard his suitcase and joined the end. American people everywhere, walking fast; all going someplace. Even their clothes looked different. America was not only a country but the whole continent.

Dad was signaling him. What was that about? Keep yer eye on the suitcase! Murdo signaled back to him. He dropped his rucksack on top of it and squatted beside them. Dad was right; there was bound to be thieves, even in airports. Thieves watched and waited. How could you tell a thief? Even if a guy was shifty or dressed poor it didnt mean anything.

People wore different clothes here. Plenty guys in short trousers; old ones and fat ones. Some wore cowboy hats. Ye expected rifles and ropes to lasso cattle. One man carried an accordeon-case and was wearing cowboy boots as well as a cowboy hat. The case was amazing. This beautiful design and all studs and shiny buttons. He must have done it himself; if that was the case what like was the accordeon! The music would be different too. This guy was more like Mexican or South American, so different rhythms and different dances, but some of it would be the same; ordinary walking and fast walking, and slower like a woman stepping or skipping along; or doing that bouncing step women did especially: Step we gaily on we go, heel for heel and toe for toe.

Dad had reached the information desk and was speaking to the man behind the counter who was old for a job like this, straining to hear what Dad was saying then looking at him like he didnt know what he was talking about. Dad was irritated and called something to the other information worker who was a black woman with thick glasses and grey hair. She also was old and Dad came away soon after looking as if he hadnt learned much at all. The way he strode back Murdo knew they were leaving. He pulled on the rucksack before Dad grabbed the suitcase handle.

So that was them now, outside the building, fresh air at last.

The heat was immediate, the sun striking into yer eyes and yer head; even breathing, ye were aware of the difference in air. But folk were smoking and that had an effect. It made him dizzy as a boy and sometimes nowadays he felt the same, especially if he hadnt had much to eat. Not since sandwiches on the plane. Hours ago. And when before that? Amsterdam; sandwiches again. No wonder he was starving.

A local bus would take them to the main bus terminal. Plenty queued at the bus-stop, including soldiers. Some were Murdo’s age or not much older. Females and males. Maybe they werent real soldiers. Although back home you could join at seventeen and didnt need yer parents’ permission. Murdo was sixteen but coming up for seventeen. He fancied the navy. Imagine Dad coming home from work: I’ve joined the navy Dad. But if it was his life, why not?

At the main bus terminal people were ordinary but mostly poor-looking. All ages, some with phones, sitting texting, checking stuff out, listening to music. A big screen gave information. Buses were late and customers had to be patient. Some had their eyes closed, dozing. Others stretched out sleeping on the floor. If ye were alone ye would be careful. Police patrolled and had a dog, maybe for sniffing drugs. They had guns too. Actual guns. Big sticks and handcuffs, talking to each other while they walked like having a wee laugh to each other, but watching people at the same time. Dad said, Dont stare son.

I wasnt staring.

If they look at ye just look away.

Okay.

He hadnt been staring but there was no point making a fuss. How long since they left home? Ages. Hours and hours. Maybe they could sleep on the bus. Imagine big comfy seats and just lying back, like really comfortable and just closing yer eyes. But if the bus was late what then?

They found space on a bench. Soon Dad had his book out and was reading. Murdo could have brought one. He didnt think of it. Because he didnt know he was going to need it. What did it matter anyway, it was too late; too late for that and too late for this, this and that and that and this, just stupidity, when did that ever happen, forgetting the phone, where was his head, that was the question, all over the place.

Across the side of the hall the police had stopped a guy and were getting him to open his bag. They searched inside, probably for dope. The guy’s clothes were out in full view, socks and stuff, underwear. He stood with his head bowed staring at the floor. It wasnt nice.

Dad hadnt noticed. The lassies too, ye couldnt help noticing them; one with bare legs and a short short skirt, quite skinny, and guys staring and she was just like standing there.

Better not thinking about stuff. Music would have helped. A nightmare without it. There was a new system he fancied but it was impossible because of money. Everything was money. It tied in with useless old phones and headsets that dont work. Dad said read a magazine. Okay but ye still heard people talk. Murdo did but Dad didnt. Dad was oblivious to everything. Murdo needed music. So if people talk ye dont hear it, ye dont piece it together. It didnt matter when or where, yer mind just drifted, away into anything, ye didnt even know, just drifting, thinking without thinking, making his mind go in a different way, just to like go cold, make it go cold, but it was difficult, difficult, just like

Dad nudged him. You sleeping?

No.

I could have been away with all the luggage; even your rucksack, I could have lifted it off yer shoulders. I could have stolen everything.

Dad I wasnt sleeping.

Ye were.

I wasnt.

Yer eyes were shut.

I was counting to ten and opening them.

Dad sighed. Ye’re too trusting. Look after yer things is all I’m saying. There’s thieves everywhere.

Murdo nodded. Dad glanced up at the destination screens, closed the book and checked his watch. Come on, he said, we’ll stretch the legs. There’s still forty minutes. A walk will do us good. Get the oxygen pumping.

Murdo was glad to be walking but they kept inside the bus station. He would have preferred going outside, even just for a look. Here they were in America and he hadnt been outside. Memphis, Tennessee; that was the song.

They found seats on another bench near a soft drinks machine. Murdo was hungry. Dad didnt seem to be. Folk had food and were eating it on their laps. Ye wondered where they all stayed. Was it an ordinary house with ordinary rooms, a kitchen and a living room? A settee and chairs and a table. He couldnt imagine them cooking a meal like toast and beans or a boiled egg, a bowl of porridge. It really was a foreign country. An old guy passed near to them. He wore a fancy jacket with curved pockets and a string tie with big jewels like a cow’s head with horns and a thing poking out his mouth—what was that? the end of a cigar maybe. He scratched his bum while he walked; skinny legs through his trousers, his shoulders hunched in. He sat down on a bench nearby then was talking out loud to himself; this wee old man. His body shape was like a walking stick. It was religious stuff he was saying. Put your trust in the Lord, put your trust in Jesus. Murdo smiled watching him.

Another man was coming past, hobbling as though his feet were bad and he called to the old guy, Amen brother amen. Maybe he was being sarcastic. Or was he a true believer? He didnt look like one; more like he was on his way to work. What kind of work? What did people work at? The same as back home, it would just be the same things; mending stuff and factories, fixing electricity and plumbing; working in supermarkets and garages, cafés. Where did they come from? Where were they all going? Some would be seeing their relatives. The old guy was talking again. His face was kind of angry. Put your trust in the Lord, put your trust in Jesus.

The funny thing was he seemed to be looking at them. Dad was reading his book and hadnt noticed, but he did eventually because of the voice. The old man raised his hand up: The Lord hath them chastened sore, but not to death given o’er.

Dad half smiled, acting as if it was nothing but how come the old man was looking at them? It was more Dad than Murdo. The old man gave him a real angry look. He said the word “Jesus” again and brought his finger down the way a teacher does.

Obviously he was cracked. Maybe he didnt like foreign people. But it made other people look across, so it was a bit embarrassing. Dad noticed too. Murdo whispered, Is it because we’re foreign?

Dad shrugged. I dont know, I’ve no idea.

When is the bus coming?

The bus. Soon. Dad smiled slightly then gazed at the floor.

Other people wouldnt know they were foreign. Or would they? So what if they did? People think things even when they dont know a single thing about ye. Dad tried to ignore the old man but that was not easy. Then he stared straight at him. But the old man stared straight back and wagged his finger: If it be the will of Jesus! He will renew them by his spirit, if it be his will. Uphold them by his love, if it be his will, I’m talking the will of Jesus.

Murdo didnt like the way the old guy was saying it, and how it affected Dad. Because it did affect him. It shouldnt have but it did. And that was unfair, so unfair. After what Dad had been through he was the last person, the very last person. He believed in God too. Murdo didnt but Dad did. Murdo knew this from when Mum was in the hospice. A minister came through the wards and sometimes spoke to Dad. Dad was okay about listening but Murdo wasnt. It was none of the guy’s business. How come he was even there? If nobody belonged to him, how come? He just hung about. Visiting Mum too, how come the guy visited her? A minister. Murdo would never have let him. How come Dad let him? Did he ask Dad first? Because Mum would never have asked for him. Never. Him being there like that, a stranger, and Mum lying there, not able to do anything, not even hearing him and him sitting beside her and talking about all that stuff. What did he have to do with it? Nothing. Poor Mum. Listening to him. Okay she was Dad’s wife but she was Murdo’s mother. Imagine he held her hand. Ministers did that. Even thinking about it. Horrible.

The Lord hath them chastened sore, but not to death given o’er. Murdo hated that kind of stuff.

***

On the bus out of Memphis he was on the inside seat, Dad on the aisle. The final destination seemed to be New Orleans but they were changing buses long before, and other changes after that. Murdo wasnt sure except they had to watch out for themselves. Dad was keeping track of things. He had all the stuff, all the information and tickets and whatever else, everything. Dad had everything. That was just how it was. He didnt tell Murdo, although Murdo could have asked. He should have, he didnt, they werent talking much.

The first stop was a wee town without a proper bus station. Nobody was waiting. The driver let two passengers off on the street. He had a smoke while getting their luggage out the side compartment then stood to the rear to finish it. Onwards again, passing alongside the main motorway then veering off on a smaller road that was quiet for long stretches. Nobody seemed to be talking, maybe a murmur from somewhere, hardly anything. Maybe they were snoozing. Murdo too. He saw a wide river and it was the next thing he saw. He surely must have been dozing. He turned to Dad, whose eyes were shut. Was he asleep? Murdo said, Dad . . .

Dad opened his eyes. It took a few moments for him to register the surroundings.

Murdo said, What river is that?

Dad squinted out the window then sat back. I’m not sure, he said. He looked again but with bleary eyes and soon closed them.

Even seeing the river! Imagine a swim. A swim would have been great. Just being on the water. If ever he got money it was a boat first. Sailing anywhere ye wanted. People had yachts and sailed round the world. They took a notion and went, and arrived at a harbour. They moored and went ashore. Anybody there? Where am I? Is this Australia? Not knowing anybody and just being like free to do anything at all, anything at all. Oh no it’s Jamaica. Jeesoh. A boat came first before anything.

The idea of a swim. Murdo was tired and sweaty. It had been cold before; now it was muggy.

Later they were in another town, large enough for its own wee bus station although parts were quite old and with broken windows and stuff, peeling plaster. The driver was taking a break and so could the passengers. Some lit cigarettes as soon as they stepped down off the bus, maybe went to the toilet. Others got out just for the sake of it; Murdo and Dad among them. Two people were leaving the bus and three people came on board. Eight o’clock in the evening and warm, a smell of dampness. Dad had the bus tickets out and was studying them against the itinerary and receipts. He glanced again at the tickets. Where’s the driver? he said.

The driver? said Murdo.

Dad muttered, I need to check something, then headed along to the waiting area and joined the queue at the information counter.

Murdo stood a moment then followed the sign to the gents’ lavatory, through a door and along a corridor at the side of the main building. A man was at the sink. He was still at the sink when Murdo finished urinating. Murdo washed his hands then put them to the hot air machine. The man was still there, and staring at him. Definitely. He was staring at him. He was. And Murdo left fast, wiping his hands on his jacket going along the corridor. He was not scared. More like nervy. This made ye nervy, stupid damn things like this. How come him and not somebody else? The guy wouldnt have done it with Dad there. Never. Only him, because it was him: oh he’s young, he’ll be too scared to do anything. That was the guy, that was his thinking, staring at him like that, and Murdo moved quickly because if the guy came after him, what if he came after him? Murdo would get Dad, he would get Dad. There was the exit at the end of the corridor and out he went.

Where? Where was he? On the pavement outside the bus station. It was the wrong exit. There were two, at the opposite ends of the corridor. One kept ye inside, the other led ye out.

He was not going back in, he was not going along the corridor. So like if the guy was there. Imagine he was there. Murdo was not going in, he was not going in. He looked for the entrance drive-in off the road; the one used by the buses. It was along to the side.

This must have been the main road, where he was standing. It was long, straight and wide. The odd thing was the lack of traffic. Parked cars but none moving. Not even one. It was a Saturday night too. Maybe this was the outskirts. Oh but the sky was amazing. Murdo couldnt remember ever seeing one like this. A kind of orange into red and so very clear. Probably it had been hot during the day, and would be tomorrow.

On the opposite pavement along was a place with its name in flashing lights: Casey’s Bar ’n Grill. Nearer to that a couple of shops with wide windows. Outside one was a huge wheel like from a covered wagon or else an old stagecoach. It was propped against a wall, just lying there. The pavement continued round the side of the building. A jumble of stuff lay there too. Now away in the distance a truck was coming. The typical style with the funnel. It was great to see. Murdo crossed the road before it came then watched it go, with two wee flags flying on top of the cabin.

The pavement was made of wood and when ye walked it made a clumping noise. The other shop was a pawnshop. A pawnshop! He hadnt thought of that. Pawnshops in America.

The huge wheel was rusty and mottled. From an actual covered wagon maybe. He touched it, then chipped off a flake of rust with his right thumbnail. Other stuff lay roundabout. Old farm tools made of iron, rusty and ancient-looking. All dusty. Everything. Did people ever pick them up! Did they ever buy anything!

This first shop was antiques and had two great-sized windows. Ye couldnt believe how good it was like all stuff from the old west. Amazing. Guns and handcuffs, rifles. A wide bowl contained arrow heads and another one with sheriff badges; Marshal of Dodge City, the Pony Express. Some were ordinary stars, others with circles and points. An Indian chief’s headdress with feathers and like branding irons and all whatever. Round the side of the building was a plough. Behind that an open space with the front part of a stagecoach, including the bit the horses got roped into. Real stuff and all just lying there. If ye had had a car ye could have taken anything ye wanted.

Next door the pawnshop. On the window ledge lay an empty ashtray full of cigarette ends, with that fusty old tobacco smell. Good stuff. Laptops and base units, consoles, tablets; digital headsets and all kinds of phones. Old stuff too, televisions and hi-fi equipment; video cams, old-style computers. Plus big hunting knives and daggers with long thin blades. Swords too and like strange-looking things, balls and chains or something. Then farther along assorted mouth-organs, two saxophones and two acoustic guitars.

And an accordeon!

It looked okay. He wouldnt have minded a go. A bit shabby but so what if it sounded right. It sat snug between a keyboard and a bass guitar. Ye wondered whose it was? Somebody from way back. Some old guy. Probably from Scotland, or Ireland, an immigrant; maybe he played in a band. Or used to—he died and his family sold off his stuff. Because they didnt have space to keep everything; it was just a wee house where they lived. Maybe the old guy stopped playing. That happened. People can play music forever then one day they give it up. So when the guy first came to America he had to work in a factory to make ends meet for his wife and family. So he shoved his instruments in the cupboard. Maybe the keyboard and bass guitars were his too, like his own rhythm section. Murdo had three guitars, one from when he was a boy, the other two along the way. Ye started on one instrument and ended up on something else. He had a keyboard too, and he was wanting a fiddle.

Then music from Casey’s Bar ’n Grill. The door had opened and two guys appeared, lighting cigarettes and continuing a conversation. A bus pulled out from the side street across the road, turning out onto the long wide road. And Murdo ran, ran, ran straight across that road into the side street entrance round to the bus park area which was empty except for Dad. Dad was standing with the suitcase and rucksack at his feet. Nobody else there. He saw Murdo and started walking towards him almost like he didnt recognise who Murdo was.

Murdo felt the worst ever he had. Ever. He couldnt remember anything ever worse before. This was beyond anything. Dad wasnt even looking at him, just nothing.

Aw Dad, Dad, I’m so sorry.

Dad nodded. The next bus is tomorrow, he said. He pulled out the handle on his suitcase, headed along to the waiting area. Murdo followed him, carrying the rucksack in his hand. Only two people were there. One was a black guy holding a sweeping brush, just watching them. The other was the woman at the information and ticket desk, she was black too. I need to phone Uncle John, said Dad, I need to tell him the situation.

Dad I’m so sorry.

Dad indicated a bench next to the door, and left him the luggage to guard while he crossed the floor to speak to the woman. She listened to him and passed him coins for the old-style payphone by the entrance. He went to make the phone call. Murdo just sat, there was nothing else. He came back and that was that, they were going to a motel for the night.

Dad walked a pace ahead out the bus station. A taxi-office was round the next corner; a few taxis were parked. Dad entered the office. Murdo stayed out. A guy with a beard and a turban opened the door of a car and gestured at him to get in. Murdo shrugged but waited for Dad; for all he knew it was a different taxi. The guy closed the door and folded his arms. A few minutes later Dad came out and passed the guy the suitcase. The guy shoved it and Murdo’s rucksack in the boot.

When the car was moving Dad stared out one window, Murdo stared out the other. What he had done was stupid and there was no excuse. If he had known the time he would never have left the bus station; never gone anywhere except the bathroom. It was that guy staring at him. If he hadnt been there it would have been okay. He should have told Dad. He was not going to. Maybe he would, not just now.

A mile farther on he spotted a shop down a side street with its lights on. There was a porch and a couple of people stood chatting. Soon they were at the motel. This was a long, one-storey building with an open corridor: the Sleep Inn. Sleep in and ye slept in, it was clever. The guy at the reception office was young, more like a student working part-time; a black guy. He did the paperwork with Dad then gave him the key.

They walked by the edge of the carpark, along the side of the building. Their room was way towards the end. Only five cars were in the carpark. Did that mean only five rooms taken in the whole motel? No. He saw lights in a few of them so other people were here. Up on the outside corridor laundry hung on the rail to dry. Farther along two people sat on chairs on the open landing gazing out over the carpark. There were no tall buildings. No hills either. They would be seeing right over to wherever. An old man and old lady. The old lady didnt look at them but the man did and he called down: Howdy!

Murdo waved up to them: Hiya!

This was the first he had spoken to an actual American. Along at the room Dad could hardly open the door. The handle was shaky and about to fall off. Then the key wouldnt go in the lock. Then when he managed it the key would not turn. Now he had to grip the handle but it shook like it would fall off. Maybe he was forcing it too much. He stood for a minute breathing in and out. Then he got it to work. Bloody squirt of oil, he said, that is all it needs.

The room had double and single beds and an old-style television on top of a cupboard. One wardrobe. It only had three hangers inside. They werent unpacking so it didnt matter. Dad sat on the end of the double bed, still in his jacket and shoes.

Murdo checked out the fridge. He was starving. Dad must have been too. Completely empty inside; sticky patches and not too clean. The microwave was working but ponging. Although ye get pongs cooking food so it didnt matter too much. When had they last eaten? Maybe there was a takeaway someplace.

The cupboard underneath the television smelled of damp but contained cups, plates, plastic cutlery and an electric kettle. In the bathroom there was a shower as well as a toilet bowl and washbasin. The handle on the toilet bowl wouldnt pull properly. Murdo jerked it a couple of times but couldnt get it going. No toilet paper! Murdo couldnt find any. He didnt need it, but what if he did? No soap either. He rinsed his hands. And no towel!

He came out the bathroom wiping his hands on his jeans. Dad was lying stretched out on the bed, hands clasped behind his head and staring at the ceiling. No toilet paper, said Murdo.

Dad sighed.

Maybe people bring their own.

What a thought.

Murdo shrugged. No towels either.

Dad raised his head to see him. Just use yer own, he said. Dad paused a moment, then added: Did ye bring one?

No.

I told ye to bring one. I deliberately told ye.

I was keeping space.

Keeping space? What ye talking about keeping space? What are ye not goni wash? A two-and-a-half-week holiday?

Murdo looked at him.

Eh? Murdo, I’m talking to ye.

Sorry Dad.

How are ye goni dry yerself at Uncle John’s? Run about the house and cause a draught?

Dad, they’ll have towels.

Who’ll have towels? Who ye talking about?

Uncle John and Aunt Maureen.

Murdo, we’re visitors. It’s called “being polite.” People bring towels when they’re staying with people. That’s why I told ye to bring one: not because Uncle John and Auntie Maureen dont have any of their own. Of course they’ve got towels. We’re guests, and we act like guests. We look after ourselves. Things like towels, toothbrushes, toothpaste, that’s what ye bring; ye bring them with ye.

Dad shook his head, unlaced his shoes and kicked them off, then stretched back out on the bed.

Murdo said, Dad maybe it’s a mistake, like the guy in the office, maybe he just forgot to put the stuff in. They might keep it all in the office.

Dad’s eyes were closed.

Will I go and ask? said Murdo. I was wondering about teabags as well. They’ve got the cups and the kettle so maybe they’ve got teabags too; maybe they keep them in the office.

Dad opened his eyes.

I was thinking too if there was a takeaway roundabout.

Dad raised his head again. A takeaway? he said.

I’m quite hungry.

Aye well I’m quite hungry too but it’ll keep till morning.

There is a shop.

I never saw any shop.

We passed it in the taxi.

Forget it.

Dad it’s not far. I’ll go myself like I mean I know where it is. It’s only round the corner.

I know ye’re hungry son I’m hungry too. It’s good ye’re offering but we dont even know if it’s open.

It was when we passed.

Aye well it might not be now.

The reception guy’ll know. Dad they’ll have sandwiches and stuff, bread or whatever, a packet of cheese; cold meat or something.

Dad sighed. Murdo, he said, I’m knackered, it’ll wait till morning.

Can I not just ask the guy? He’ll tell me. If he cant I wont go like I mean it’s easy to do and just having a walk Dad . . . Murdo shrugged. I’m really hungry. The microwave’s working too I mean like maybe I could get stuff to cook like a frozen meal. Beans and toast or something.

That’s getting complicated.

Well just sandwiches.

After a moment Dad said, Okay. But nothing that needs cooking. See if ye can get a loaf of bread and the cheese separate. And teabags, get teabags.

Will I get water?

Check with the guy, maybe tap-water’s okay to drink. Dad took money from his pocket while Murdo pulled on his boots. He passed him a twenty-dollar note. Will that be enough d’ye think?

I dont know, said Murdo.

Dad passed him another five.

***

He checked with the guy in the office. The shop opened till late. He forgot to ask about toilet rolls and towels. He would do it on the way back. It was just good to be walking. Warm and with a nice smell, and different sounds; insects and birds maybe. For a Saturday night it was quiet; not like a town. No pubs or anything, cafés or takeaways; nothing like that. The houses were mostly single-storey buildings made out of wood. Some gardens were cluttered with junk; others stoned over as parking spaces. At one house music from an open window. People sat outside, laughing and talking; black people; kids too. They saw him passing.

He reached the traffic lights and turned the corner. The lights were still on in the shop. There was hardly a pavement. It was quite strange; ye had to walk on the street or else on the edge of people’s gardens. Roots of trees were growing in some and ye could have tripped over. Two young guys were on the porch entrance to the shop, just hanging out; watching him. They looked about fourteen.

It was an ordinary kind of shop but with all different stuff, in-

cluding magazines and books and like a medicine counter. Murdo lifted a basket and saw the girl serving. She was good-looking, with bare shoulders and a blouse that was loose. What age was she? Just about his, whatever, sixteen or seventeen. She saw him and was staring. He was white and a stranger. Other customers were black. He passed along the first aisle. He didnt know what things were there or what they cost. Some were the same as back home; same tins and packets, soups and breakfast cereals. Other stuff ye had to look at twice or else see the labels. He was thinking for sandwiches. Dad wouldnt care except how much it cost. They would save money if they made their own.

Murdo found the bread but the shelf was near empty; only wee loaves left. He took two. But for butter ye would need a whole tub of butter and that was too much. And how much cheese? Not that much. Unless there was cold meat. The cold counter had big thick sausages that looked good but maybe ye had to cook them. He picked up a packet to see and saw the girl looking across like if he was going to steal it! Ha ha. A packet of sausages. They were no good anyway if ye had to fry them. Farther along he lifted a pack of cold meat then checked out the cheese counter. A pack of ready-cut cheese-slices. Cheese was cheaper than cheese-slices but ye needed a knife to slice it. Tomatoes made good sandwiches too but ye needed a knife for them.

The girl was watching him again. How come? She knew nothing about him except he was white. Probably she thought he was American. He kept on down the aisle but his face was red now, if she really did think he was stealing. He had to lift stuff to see the price. He didnt have any option. Prices were on everything and he was able to check it against the twenty-five dollars. Cheese and bread, a carton of orange juice and one of milk. A packet of lettuce and a bottle of water; a wee tin of beans and a carton of fruit yoghurt.

The girl was serving a woman but looking across at the same time. So was the woman. Maybe they both thought he was stealing. If ye took too long people thought ye were waiting yer chance. He was just working out the money. If there was change out the twenty-five he would buy a couple of bananas. A few were a reduced price in a basket next to the cash till. Bananas made good sandwiches too. They were overripe but would be fine inside. He queued behind the woman.

The girl’s name was Sarah: the tab on her blouse said it. An old-fashioned kind of name. Murdo gazed at the floor not to look at her, then away towards the door. Really she was beautiful. A girl’s bare shoulders always look good but hers really really did. And just a beautiful face. That is what ye would say. A smooth face like ye get with lassies and her hair pulled back so it was like her forehead was really smooth too, and how her neck went, then her boobs too like her cleavage, she was just really good-looking.

Then it was his turn and she ignored him. She didnt even look at him. Although he was the customer and she was the server it was like up to him, he was to talk or whatever. That was wrong. Definitely. And he was blushing again. She lifted the grocery stuff out his basket, scanning it through the machine.

Then he noticed the prices on the screen, they were different to the labels. Everything was dearer. Every single thing.

Murdo waited to see the total. It was way more than it should have been. She didnt say a word, not looking at him, just waiting for the money. Except he didnt have enough. It’s too dear, he said, it’s charging too much.

Huh?

Yer machine’s charging too much.

She frowned at him, not understanding him. He lifted the first thing to show her, the packet of cheese, it dropped out his hand. She picked it up. He pointed to the price on the label. It says four forty-nine but the machine charged more, I watched it. The same with everything. Your machine charged more, it’s just like every single thing it added on money. The total’s all wrong.

She stared at him. Oh you’re talking about tax, she said. You got tax on these things.

Tax?

Each one you got there it’s got the price then it’s tax on top. Is that what you’re talking about, tax? The girl held her hand out for the money. You’ll see it on the receipt.

It totalled more than thirty dollars. He didnt have enough money. He showed her the twenty-five. You’ll need to take stuff out.

Huh?

Murdo passed her the lettuce and the yoghurt. Does that make it? he asked.

Mm. She started packing the food into a brown bag, paused to place the two tins on a tray behind her. To the side of the cash register was the basket of loose bananas. She did a new cash total and gave him the receipt. He was waiting to see the change. A little more than one dollar in coins. How much for bananas? he said. Can I get two please?

Pardon me?

Murdo held out the change to her. Can I get two bananas please?

She packed in two bananas beside the rest of the food and pushed the full bag across.

Thanks, he said.

Sure. She watched him lift the bag. Where you from? she said.

Scotland.

Scotland?

Yeah.

Mm.

He held the bag close to his chest and exited the shop, up along the street and the main road. He started smiling. Because it was good. He felt that. Just everything. America. He liked it. It was different. Had she even heard of Scotland! Ha ha, maybe she hadnt. It was strange to think. America, an American girl. Imagine she smiled at him. Maybe she did. She could have.

Mum would have liked it here. Everything was new; away from the old stuff. Fresh air and breathing. Fresh breathing. Everything! Murdo felt that strongly. He didnt care about stuff. School and the rest of it. They would all wonder where he was. Ha ha. Here. Thousands of miles away. It was great, just bloody great, and he walked fast: food to eat. Dad too, he must have been hungry.

It was dark by now. He remembered the toilet rolls. In the motel reception office the guy was on the computer. He had a wee pile of books beside him. He must have been a student right enough. Murdo said: We dont have any toilet rolls.

Huh?

I mean like toilet rolls?

You need toilet rolls huh?

Well we dont have any.

The guy turned and opened a cupboard door, withdrew two and gave them to him.

Do we not get any towels?

Huh, you want towels?

Yeah well there arent any.

Okay.

Are we not supposed to get towels?

Sure, yeah. Who’s in the room?

Me and my father.

The guy opened the same cupboard door, brought out two towels and handed them across.

Thanks, said Murdo.

Sure.

Back in the room the television was on but he could see Dad had been dozing. Dad yawned, watching him come in the door and carry the towels and toilet rolls into the bathroom. Murdo laid the food and drink along the foot of the single bed then knelt to unlace his boots.

Dad said, Well done son.

The office guy was fine. He just gave me the stuff.

Good, said Dad. What about the shop? How was the walk? Did ye meet anybody?

No.

Dad yawned. Did ye get teabags?

Instead of answering Murdo knelt to retie the bootlaces.

Did ye not get any? asked Dad.

No but I will now, said Murdo, quickly knotting the lace on his left boot.

Dont bother.

No Dad I’ll go.

No ye wont.

Dad ye need tea.

I dont.

Ye do.

I dont.

Dad, ye need tea!

Calm down.

But Dad

I dont need tea. We have needs in this life but tea isnay one of them. I’ll survive. Dad lifted the towels and toilet paper and entered the bathroom.

Murdo sat a moment then switched on the television. He watched it while preparing the food. When Dad came out the bathroom he saw it on top of the cupboard. Good stuff, he said, well done.

I’ll go for tea in the morning, said Murdo.

Dont worry about it.

No, he said, I’ll go.

***

Last thing in the evening he went in for a shave. He hadnt done it for a while. The mirror over the washbasin was more a large flat tile but it worked alright for looking into. There were these pimples around his chin. When he shaved the safety-razor cut them, it cut off the tops. The risk was more pimples. The blood out a pimple caused that to happen. It made them spread. Ye had to be careful if ye scratched them, it could leave scars and brought plooks and boils. Ye were better patting yer face dry with the towel instead of wiping it.

Mum used to give him a separate towel. It was her told him about patting instead of wiping because wiping makes pimples spread. His werent as bad as some. But he didnt have a heavy growth. Some guys did. Dark hair meant ye shaved more. If ye were black ye wouldnt go red at all. How could ye? Then with pimples, probably it disguised them. Ye wouldnt see them as easy if ye were black. He could never imagine that girl in the shop having pimples. Girls get pimples but ye dont think of it. Sarah. It was a good name. He liked her and he could imagine her; she had good lips. People have different lips. He saw his own in the mirror and what did they look like? Thin; thin lips. A guy he knew played the pipes and he had thin lips where ye might have expected thick ones. Because playing the pipes, it was what ye would expect. Some guys were horrible-looking; gross, the worst imaginable. Yet they had girlfriends; wives and children too. So they got kissed. Gay guys kissed each other. Everybody kisses and gets kissed.

When he dried his face there were spots of blood on the towel. The usual wee cuts round his chin and neck. He splashed on the cold water again, patted his chin dry. Dad had the television on when he appeared. He looked over. Murdo said, I was shaving.

Oh.

Murdo shrugged. He sat on the bed with his back to the top end. It was relaxing watching television, except Dad kept the volume low and there were no good programmes and the adverts were like every second minute, the voices droning on, but it was comfy, and thick pillows just like sinking in. Dad woke him later. Ye’re better getting inside the sheets, he said.

Murdo undressed and got inside the sheets. A while passed and he was awake again. This time it was the middle of the night. The bedside lamp had been switched off. Although the curtains were drawn light came through the underside. He thought he heard voices. The television was off. One voice mumbling. Was it Dad? Was he praying? Murdo couldnt tell, not individual words. He didnt want to listen. Dad prayed when Mum died. Murdo didn’t—except only before with the pain Mum suffered ye needed to block it out, how she held his hand, gripping it, because with the pain, gripping his middle three fingers like squashing them tight, the pain she was in. Please God make her not in pain, please God. But she was, except with the medication heavier and ye saw her eyes, poor poor Mum, inside her eyes, just like hollow, a hollowness. People said, Oh ye must pray. Murdo tried it before. Not after because what did it matter. People prayed at the funeral. What for? So they wouldnt die? Oh God please make me live forever.

The voice had stopped talking. It must have been Dad. Unless it was Murdo talking out loud. Or in his sleep so he woke himself up. That happened. Dreams woke ye up. Or nightmares. Or something between. Not dreams and not nightmares, and not like wet dreams or whatever, and not music although sometimes music but weird music just like systems and things to do with planets, alien worlds and spirit worlds; worlds for dead people. Stupidities all crowding in, crowding out yer mind; the last nonsense ye heard on television, the more stupid the better. Why did they not just shut up? Some voices Murdo hated and ye wanted to drown them out.

What time was it? Who knows.

Mum and his sister, Eilidh. What world were they in? A spirit world, always surrounding you and you surrounding it. You are within it but they are within you.

***

He was awake early next morning and lay on in bed. Only a minute then he was up and the clothes on. Dad was sleeping. He didn’t want to wake him. The bus was not until mid afternoon so it was okay. Dad liked long lies. The same when Mum was alive, the two of them. There were times they didnt show until after eleven o’clock. It made ye think of something else. So what yer Mum and Dad? if it was sex; sex is sex.

Murdo slugged milk out the fridge and left it at that. Teabags and Sunday breakfast. On his way out he lifted a ten-dollar note from Dad’s money and clicked shut the door. With luck he would be there and back before he wakened.

The same five cars in the carpark. A clear blue sky. Already it was warm. So peaceful. What other day could it be but Sunday! Is there something beyond enjoyment! This was more than enjoyment! No cars hardly at all. He was hearing sounds but quiet ones; insects and birds. Definitely. Mum would have loved it.

The sensation that he was seeing everything but nothing was seeing him. The road was here and him walking it. Nobody else. Not Dad and not anybody. He didnt know anybody. He hadnt seen Uncle John and Aunt Maureen since he was a baby. He didnt remember them. Who else? Nobody. Except that lassie in the shop, if ye could say he knew her. But he did. Sarah. And she knew him. Ha ha, it was true, she knew he was Scottish, whatever age she was, maybe older than him, but not much like if she was seventeen; another couple of months and him too. Ye were a man at seventeen. People said that. Sixteen is a boy and seventeen a man. Oh what age are ye? Sixteen. Wait till ye’re seventeen.

Would she be there? Maybe. Although late last night and now this morning: that was long hours to work. A girl like her who was very very good-looking and like just very very pretty, she was still a girl working. So if it was long hours that was the job. Otherwise get another. Ye needed money. That was him too, he needed money, he needed to work. So he needed to leave school. Things came back to that. It didnt matter America or Scotland.

He turned off the main road, going along the side street and hearing music, the closer he got, it was accordeon. A waltz. Jeesoh. People say about their ears playing tricks. With him it was his brains and floating away someplace thinking about whatever he couldnt remember, maybe his sister was there. He never knew until he “woke up,” although he wasnt sleeping.

Murdo and the music. Walking in the beat. The beat was him walking, walking in the rhythm. Going along the street and nobody else. This waltz playing; a nice one with a real good feel, that proper rhythm there for the dance; relaxed, yeah, that was the swing, doodilladooo. That feeling too he had been here already. Or was here already. Not talking about last night.

He approached the shop. It was open. Nobody at the entrance porch. Instead of stepping onto that he kept walking, following the music round the side of the building. A few trees were here, scrawny ones. He stayed behind them, so they wouldnt see him. An old lady, the accordeon player, sitting on a chair wearing a big hat and the girl out the shop—Sarah from last night—playing washboard, stepping from foot to foot. Another lady sat next to her, not as old, but quite old.

The old lady and the girl, it was great seeing them, something just beautiful about it, seeing the two of them there in the music. The accordeon itself; cream-coloured and as fancy as ye ever would see, light glinting in the morning sun, and that brilliant sound! What a sound! That was special. That was so special.

And the girl scrubbed it along facing the old lady who nodded her head on that two three beat rhythm, glancing around at the folk watching, smiling a little but only in the music, like how some musicians did that even when their eyes were shut. This lady kept on looking, seeing the people watching, keeping her eye on them. Murdo liked that. This was her playing, she was playing. She had her way and there she was.

Murdo didnt move in case people saw him. He was not hiding, only keeping out the way.

The other woman on the porch was not so old as the musician. But what age was that? Murdo didnt know. She had a hat on too, with a fancy sort of gauze stuff trailing down the back. She sat upright with her feet firmly to the floor, moving her right hand to beat time in a sharp movement like cutting or chopping; this was her right hand beating time but it was the three beats and her wrist jerking: flicking, cutting and flicking. She could have been on drums the way she was doing it; this rigour she brought to it, which seemed to set up a response like ye sometimes hear in music:

I told ye so, I told ye so, I told ye so.

A lot of musicians did that. They played something to you and you played something to them; stupid things:

you should know better, you should know better

behave yerself behave yerself

dont you start, I told ye; dont you start, I told ye

Naw ye didnay, naw ye didnay. I told you, I told you.

That was the other musicians telling ye, giving ye a wink and a nod of the head. It was two-way. You were on the melody. Behave yerself. That was the rhythm. The rhythm was telling ye to behave yerself. Guys Murdo played with did a lot of that for fun. And it was fun. You liked it and so did the audience and the dancers danced and off ye go, the dancers danced and away ye go, tricka tricka tricka, tricka tricka tricka.

The song ended.

Murdo wondered what would happen but nothing did happen. Somebody clapped and somebody laughed, and the accordeon player spoke to people. This was a community place composed of back gardens running into each other; some had fences and some didnt. Kids played wherever; girls throwing a ball and a couple of boys horsing around. A dozen folk were sitting on chairs, dotted about the grass. A few were standing.

The accordeon player spoke a few words to the girl then it was one, two and away they went into another. This was an upbeat number with a real driving rhythm, but in that same style again. But then it stopped. The old lady broke off out of nothing, and spoke a few words to the girl, then played in from a couple of lines before, and stopped again, and restarted, and off they went.

They were rehearsing! Of course! It was the real stuff. Ye knew that just by listening. It was so so obvious. This old lady was special! Jeesoh, man! Murdo was chuckling, and felt like laughing!

There was a lyric this time; the old lady on vocal driving it on and jees she really was something! God . . . And the way people responded to her. They knew. Murdo couldnt make out the words, then realised why: it was French! She was singing in French! Maybe some English. The girl and the lady with the fancy gauze hat were chorusing the line endings. It was a new kind of music for Murdo and exciting how it rocked along, that humour too, and funky, just brilliant for playing, and for dancing; the kids were jigging about. Murdo chuckled then was startled to find a guy standing next to him and right there in his face; angry-looking, so angry-looking. Murdo stepped back. The guy spoke in a low grunting voice. What you doing here? Huh? What you doing here? You shouldnt be here; this aint your place.

Eh it was just eh . . .

This aint your place. What you doing round here? What you spying on us!

The music had stopped. The guy stepped forwards and pointed Murdo out to them. People were staring. Murdo was embarrassed at being caught but was not spying if anybody thought that. Why would he spy? It was music. He saw the girl at the side and tried to smile but couldnt, but he called to her: I’m not spying.

Now she recognised him and she raised her arm. Hey! I know him! He came in the store last night.

This aint the store, said the guy.

Oh he’s foreign Joel. Hear him talk, he’s not American.

The lady with the fancy hat said: The poor fellow! Not American! Mon Dieu!

He didnt know about tax! said the girl.

Both women laughed. The guy who had caught Murdo was still annoyed but no longer angry-looking. He was older than Murdo but not that much.

Murdo shouldnt have been there at all because it was other people’s gardens. He knew that. It was just the music. I heard the music. Murdo said, I was going to the shop. I heard it and just eh—I followed it round.

The two women found this funny. The accordeonist said: Hey now children he is enjoying my music. You think I didnt see him? I saw him from early. He’s audience! You think I wont see audience?

She dont get that much nowadays, said the other lady.

The accordeonist raised her hand. I saw him the moment he come in these trees there! She studied Murdo:You like the music?

It’s great.

Great huh! She gazed at him.

Yeah. He shrugged. I play too.

She continued to gaze at him. Oh now, she said, I know you play. I saw how you were looking. What you play boy Cajun? You play Cajun?

Eh . . .

Come up here! she said. Murdo went immediately to the porch. You Irish? she asked.

No eh, Scottish.

Scotland, said Sarah.

It’s another country, said Murdo. It’s near Ireland, and the music’s like not too different I mean like eh . . . Murdo sniffed, and gestured at the older lady’s accordeon. I would play, he said. If ye think I mean eh if ye wanted me to I mean . . . Murdo stopped, aware of Sarah watching him and he blushed immediately, tried to stop it but couldnt. Last night she was almost angry. Now she was friends and really she was beautiful. Her name too, Sarah, an old name. Old names were good. The name “Sarah” was right. As soon as ye said it ye knew it was hers.

The accordeonist made a comment in French to the lady with the fancy hat, then studied Murdo. She nodded to Sarah: Go get him a box honey, get him the turquoise.

Sarah went to the house behind the porch.

So boy what’s your name?

Murdo.

Murrdo. She grinned, stressing the “r.” Well now Murrdo my name is Miss Monzee-ay: people call me Queen Monzee-ay. Can you say that?

Queen Monzee-ay.

This here is Aunt Edna.

Welcome, said the other lady.

Queen Monzee-ay waved at the guy who had surprised Murdo. He is Joel, he is my grandson. Sarah on rubboard is his sister.

Sarah is my granddaughter. So now you know us. So how come you are here?

Well I was going to the shop like I mean the store.

No now boy I’m talking here, in this place, this town. This is Allentown, huh? How did you come by here?

Aw, well, what happened, we missed the bus. Me and my father eh . . . we missed the bus, like that’s why. We’re just passing through.

Aunt Edna clapped hands. Now he’s got it!

Queen Monzee-ay chuckled. Sarah returned now. She was wearing a hat; a daft round thing, but it looked good and made ye smile to see. She held the accordeon out to him. The top she was wearing didnt have sleeves so her shoulders were bare like last night. Thanks, said Murdo. He took it from her, pulled it on and touched the keys.

Queen Monzee-ay said, Now Murdo you play how you play.

The accordeon was tuned to B-flat. He hadnt played for a while and his fingers were not flexing right. A strange sensation too like the skin on his fingers was too tight or something and he was wanting to widen the gap between the tips of his fingers and the fingernails. People were watching but he was okay. They were wanting him to play properly. He knew they were and he wanted them to hear. That was that, he played a jig he had learned a few months earlier. He was still with the band at that time, before Mum’s health deteriorated. It was fine, he knew it was fine. Some kids were here and he hoped they might dance. They didnt but it was okay anyway. Aunt Edna applauded: Bravo m’sieur.

Queen Monzee-ay said: Want to play it again?

The same one?

The same one.

Off he went the second time. He saw her preparing to play, then she did. In she came, she played a rhythm almost like straight into him. Brilliant. Murdo played the jig a little differently now; shifting ground was how he thought of it, but it meant him doing fast steps. Mum had described it as “capering.” She enjoyed it when he “capered.” He sometimes did it with the band, jigging about, just depending how it went and if he was taking the lead. If he was playing a jig he was doing a jig. That was how he thought of it. Ye were not just playing for the tune ye were in it. He did it here with Queen Monzee-ay, and she played into him. Her name fitted: a real Queen, real music, real style.

She played another of hers with Sarah on le frottoir—which was rubboard in French. It was a fast number, swinging, rocking. Just so good. Queen Monzee-ay looked for Murdo coming in like she had on the jig and he was ready for it. She was fast. Thinking of

somebody old, she said how she was slowing; not her brains but

her fingers. Murdo didnt think so, my God. Arthritis she said but it was a joke how she said it. She was not slow at all, not lightning fast but near to that.

“Zydeco” was the name of the music. Murdo knew nothing about it and had never even heard the name before. He had heard the name “Cajun” but not music so much as a place, like a land or a country, the “country of Cajun.” But he had never heard the word “Zydeco” before.

Sarah was laughing, and that daft hat she was wearing, just so—how to describe it? Murdo didnt know except it made ye grin, make anybody grin. More like a sailor’s cap. Back home ye saw rich guys on yachts wearing them. Sarah was great. She was fun. A real lassie just laughing. That was her! She was just like special! Ye knew it! Anybody would! The real granddaughter. She was Queen Monzee-ay’s real granddaughter.

Queen Monzee-ay led in on another uptempo number, with a smashing chorus line where Sarah joined in, emphasizing the Frenchness. It was sexy how they did it and it made ye laugh, really, good fun:

Ooo la la something something

Com si com sa something something

And Aunt Edna too, whooping and clapping, her right hand beating time, wrist jerking, the flicking and cutting movements; shouting comments in French; all just kidding on, she was kidding on and kidding him on too. He knew she was. He didnt care. It was just the best, really, for Murdo it was the best fun and he hadnt had it for a long time, for a long long time.

At the doorway of the next house a man and woman appeared and were listening. Sarah came up close to Murdo: Ma and Dad, she said.

Queen Monzee-ay wanted one from him now and he played a Canadian waltz; from Newfoundland, the nearest part of Canada to Scotland. It had a cheery effect. Sarah’s Ma and Dad danced to it. Queen Monzee-ay played a harmony line and at the end she said, Hey now Murdo, see what you can do with this one. And it was another good rocking tune of her own, she called it “Fresh Air Does You Good!” L’air frais fait du bien! Just add the croutons, she called.

Midway through she stepped aside, keeping a rhythm and pushing for him to take the lead, urging him on. Show me show me. She may as well have been shouting. But it was fine and in he came, using a thing he had been working on a while ago. He knew it inside out and could do what he liked with it, jazzing it up with his take on this new way of doing it. It was fine, he knew it was. Queen Monzee-ay focused on his playing, giving the briefest of smiles. She came up close and laughed, You are the croutons boy!

He kept it going then caught her signal and stepped aside. She came in where the next verse should have been and ran somewhere else. It was brilliant what she did. Her playing reminded Murdo of a guy used to play mandolin in the band. He was only there a short period but for the time he was it was one of the best times ever they had. Where he led you followed. Where to? Anywhere. Wherever he took ye! That was where ye went. His playing led ye into it, and ye got there and just jumped off. Murdo loved that, and here now with Queen Monzee-ay. She was in that league; she brought it out. It was there in ye and she brought it out.

When they stopped for a break she and Sarah did funny curtseys to him and he did a stupid kind of bow. Queen Monzee-ay said, How long you been playing the box Murdo? She pointed at the turquoise. I’m talking that one right there. You played that one before . . . !

Murdo smiled, then replied, Yeah, it’s kind of good.

So how long you been playing?

Well like since I was a boy, nine or ten.

Yeah.

I’m coming up for seventeen.

Old man huh! Queen Monzee-ay chuckled. Sounded good huh, two boxes?

Definitely. Two boxes is always like well special, it can be special.

Yeah. Yeah, it sure can. When it happens son but aint too often it happens. Session this morning now it’s toward a thing we’re doing two weeks from now. You know I am retired!

Sarah cried: Gran you’re not retired.

Queen Monzee-ay smiled.

You’re not retired.

Sure honey, I can do gigs, one-off gigs.

She got to be invited first, muttered Aunt Edna.

They all invite Gran, said Sarah.

Queen Monzee-ay winked at Murdo. Blood of my blood.

Sarah said, But they do invite you they all invite you. If you see on YouTube, you dont look but if you did, these old clips and what folks are saying.

I know. Queen Monzee-ay smiled.

They all want to invite you.

Yeah and the band honey, like this time too, they want the band alongside me. I said no to that. Queen Monzee-ay shrugged, and said to Murdo, I dont mobilise the boys nowadays except it’s something worthwhile, and there aint much of that these days.

Zydeco dont travel, said Aunt Edna.

Oh we get around some, said Queen Monzee-ay.

Only they dont like to pay, muttered Aunt Edna. Oh please come please come; please come play for us Miss Monzee-ay you are a legend, an all-time star of the world; you are the Queen of Zydeco music. Only we cant pay you no money!

Queen Monzee-ay chuckled. She still gets angry!

Sure I get angry. You got to live on fresh air.

Sarah’s brother Joel had brought them coffee on a tray. He also brought drinks for Murdo, Sarah and himself; fizzy stuff with ice and bits of ginger and green herb leaves floating, but tasty.

Oh Aunt Edna, said Sarah, tell Murdo about the band not getting paid that time like when you brought out the “piece”!

You tell him. Aunt Edna said, I need to smoke.

Yeah, said Queen Monzee-ay, taking off her accordeon and propping it against the wooden surround. She rose to her feet, massaging her side.

Both the older ladies smoked. They lifted their coffees and moved from the porch to where chairs were set on the grass. They sat there smoking cigarettes. An older man came to sit with them and they chatted, out of earshot.

Sarah continued the story: You know a “piece” is a handgun Murdo? Aunt Edna helped Gran and the band out sometimes, like on the road? Organising the money. Joel and me grew up on these stories and they are so wonderful. Our mother told us too, from when she was a kid. Gran took her on the road.

Jeesoh!

Yeah, said Joel. All over. That was Ma’s education like dives and joints and blues clubs man zydeco and jazz and like whoh! She like . . . man, that was her, that was her education.

Murdo laughed.

You play in a band? said Sarah.

Yeah well . . . Murdo looked at her.

You always want to play music?

Murdo shrugged. Yeah.

She’s a writer, said Joel.

I’m not a writer.

Yeah you are.

Sarah sighed, closing her eyes. I want to be a writer.

She’s going to do the course, said Joel. It’s like a college course?

Dad says I should go to New York City but Ma says it’s too cold.

She means dangerous, said Joel. New York City is dangerous.

It’s not dangerous.

Ma says it is. Dad too.

Oh yeah they want the west coast, but how dangerous is that, like LA? My God! They take pistols to class.

No they dont. Joel chuckled.

Yes they do.

No they dont.

I dont care, said Sarah, they got courses anyplace you want to name; Creative Writing Programs, and it’s like anything you want; poetry and fiction-writing; feature movies; documentary you know like politics; even a novel, imagine a novel! Oh my God! Sarah danced a step, then paused and sighed. Gran lived on the west coast for years. Her and the band . . . Sarah sighed. Dad says I dont need to go anywhere, they got courses here in Mississippi.

Huh! Joel shook his head.

Yeah, said Sarah, but it’s the program’s important Joel and they got some closeby. Dad says so. Ma too.

Oh yeah, yeah, they just want you home.

Sarah was silent for a moment. How come you are here Murdo?

Oh. Well, yeah . . . Murdo frowned.

Like here in Allentown?

Yeah. I dont know, we just eh . . . we were traveling to Alabama and that is east really; so how come Allentown like heading south, yeah, I dont know. I looked at the map in the bus station and it was like how come we landed here if it should be east?

Didnt you know this was Mississippi?

Mississippi? No, I mean like not Dad either, my father, I dont think he knew either.

Sara and Joel grinned.

Dad’s doing the directions. I think it was bad information up in Memphis like us getting a bus from there then like missing the bus here; even the bus driver I mean he was not helpful.

You missed the bus here? said Sarah.

Yeah well anyway who cares.

Queen Monzee-ay was watching from her chair, and she gave a wave. Murdo waved back, and got a bad feeling in his stomach. It sounded like he was poking fun at Dad and he wasnt. He didnt mean to. It was me anyway, he said. I forgot my phone so like for directions. Murdo shrugged. My Dad’s fine, he said. Really, he’s fine. It’s not his fault at all, it’s mine. Missing the bus was my fault like I mean not his. It’s just eh we dont talk that much really, being honest. My mother died eh . . . Murdo smiled. Sorry, he said, just eh . . .

Oh Murdo, said Sarah.

He scratched his brow. Yeah, quite recent, so it’s . . . it’s been tough I suppose really, ye would say. Dad especially because like my sister . . .

Sarah was staring at him.

God, he said and breathed in. What I mean like she died as well sorry, I dont mean to be saying this like I mean sorry, it’s a long time ago like I was only nine, jees I mean a long long time ago.

Oh God Murdo.

Yeah, she was only twelve. Murdo smiled, not looking at Sarah; nor at Joel, but away way over their heads, the heads of people; almost like he was floating, his voice coming from someplace else.

Sarah’s hand was on his wrist. Oh Murdo.

He opened his mouth to take in air. Joel was looking at him as well. Murdo shrugged. Just to tell ye, he said, it was a tumour, like hereditary. Through the female line. Murdo bit on the side of his lower lip. Males dont get it, he said. So the likes of me, I’m okay and Dad I mean. It doesnt affect us. It’s weird with Eilidh but—my sister—even just now, I open the door and it’s like I expect to see her.

Murdo grinned. She’s more of a pal. I think of her like that; a pal, a pal that died. Jeesoh, sorry. Murdo scratched his head. The turquoise accordeon was where he had left it.

He made a movement towards it, he wanted to play one for Sarah. Joel too but Sarah especially. Joel wouldnt mind; brothers and sisters. Brothers and sisters were fun. This tune too, it was a fun thing he had been learning; an old fisherman’s song, just stupid stuff about being fed up with the cod-fishing and then getting married and being fed up with that too if yer wife was ordering ye about all the time, so ye were like glad to go back to the fishing again. And ye had to know what a cod was like: cods are huge! And wives, wives are wives but they are girlfriends too.

He reached for the box, pulled it on and started right in on it, playing right into Sarah so she had to step back, and she was so taken by surprise she kind of shouted and it made people look. Joel laughed. Murdo sang the lyric when he played it, jigging about on the chorus. It was how he practised too. He wasnt great on vocals and didnt do it much but on this one he did.