Читать книгу The Museum Of Doubt - James Meek - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

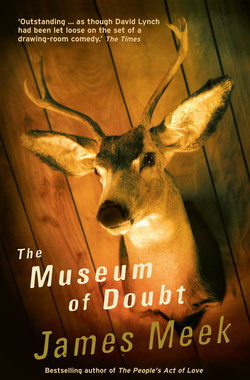

The Museum of Doubt

ОглавлениеI want to give you a demon. I want to give you a demonstration of something unlike anything you’ve ever seen before.

I beg your pardon? she said, Bettina Dron, bed and breakfast proprietor.

I want to give you a demonstration.

He was white tinged with yellow, like splatters of curdled milk, and hair black as a rook in a birdbath. It sizzled up thick and sleek from his scalp, went frying down his chops in whirling vortextual sideburns that ended suddenly, not cut, not shaved, it went from thick to nothing, from jungle to wax. There were moles on his cheeks with the hair pouring in a spout from them like from guttering after a downpour. It was dark and fine. Without touching him she knew his flesh was hot. A thick car crouched behind him on the drive.

Jack Your Firm’s Name Here, he said, sitting next to her on the sofa, their knees almost touching. He smiled. Bettina put one hand to her mouth and another to her heart, it’d doubled its speed. His teeth were so beautiful.

Call me Jack. That’s my Christian name.

Bettina. Her fingers turned her wedding ring.

Why not rent my name? said Jack. I travel the length of the land. I’d be Jack Pinetops-Guesthouse. I was Jack Microsoft for a while but after six months they wanted to upgrade me to a new version and I couldn’t afford the facial surgery.

Bettina was tempted even though her B&B wasn’t called Pinetops. It was called Dron’s B&B. In the furthest synapses of her brain Pinetops had crackled unrecognised, unspoken, till now. There was a regiment of pine trees on Hill of Eye, and from the upstairs window you could see the tops of them. She asked Jack for a price.

A price? said Jack. He smiled, his eyes widened half an inch and his eyebrows seesawed queasily up and down. Surely you can’t mean money? Do they still use money in these parts?

I’ve got a Mastercard.

Mastercard! My dear Bettina, Jack Transaction Pending hasn’t been Jack Mastercard for many a midsummer moon. Do you have any water? I’m thirsty. Can it really be true that you haven’t heard of the Friedrich Nietszche Marketingschule? Every morning we chanted in unison: Does a mother expect to be paid for loving her child? Prices! Bettina, I’m touched.

Tears shone in Jack’s eyes. He took a glass thimble and a packet of peanuts out of his pocket. He scooped the tears into the thimble, ripped the packet open with his teeth, downed the liquid and emptied the nuts in after them. With his mouth full, shaking his head, he went on: To think I would have come here to sell you something. To think I would have come all this way in order to exchange some – some good, some item, some simple service for a unit of currency. Oh, Bettina! For you – do you know, I almost would. But there’s no need. I may appear to you to be a salesman. I have things to give, things to show and much to explain. I have nothing to sell. You may ask: But is there a product? A product, dear Bettina. There are many products. You might as well enter a forest glade on a sunny spring day and ask, but is there a leaf? You might as well look down on the city and ask, but is there a window? Excuse me for one moment.

Jack got up and ran to the kitchen. He stood with his back to the sink and bent backwards till his spine was u-shaped. He slid his mouth underneath the tap and reached out to switch it on. The water gushed in a smooth stream down his throat, which had no Adam’s apple.

Would you like a glass? said Bettina, standing in the doorway, stroking her fingers.

Jack shook his head. Steam wisped from his mouth around the silver tube of water.

Would you not rather use the cold tap? said Bettina.

Jack switched the tap off and sprang up straight. He shook his head and gestured her back to the lounge. She sat down and he squatted on the rug between her and the fire, where pinelogs were burning. The hot water had put colour in his cheeks. His face had turned a chilly pink, like frozen cooked prawns.

Bettina, we’ve moved beyond money, he said. The forces that summon objects to you must be more powerful, more real than money. The force of time, the force of life, the force – dearest Bettina – of love. Tell me this. Have you worked your whole life to earn enough money to get the things you want for yourself and the people you love? Have you?

Yes I have, said Bettina.

Of course you have! cried Jack. Now, let’s sweat the fat off that proposition. First you want to take away the earning and the money. That’s just a mechanism. Do you have to see your heart beating to know that you’re alive? We need to see the big picture. So what do we do, we climb onto the roof and go up the ladder and get into the basket of the balloon and fly up ever so high, ever so high, till we look down on the world below, and everything looks so very different, so much simpler than it did from down on the ground, doesn’t it. Doesn’t it, Bettina? What do we see from way up there when we look down? Mm? D’you know? Mm? Of course you do. We can see the truth! We can see the big, plain truth. And you know what that truth is, don’t you. Yes. The plain truth is that you’ve worked your whole life to get the things you want.

But just tell me one thing, Bettina. Just one little thing, mm? Not a big thing, a tiny little thing, but ever so important. Here’s the thing: what’s work? Mm? What’s work? Hard labour? Climbing the stairs, gardening, is that work? Is it? Breathing, is that work? It can be difficult sometimes, we all know that. Or cooking, frying eggs, making a sandwich, is that work? Can be, may be, might be. Maybe it’s leisure. Maybe you like it. Maybe you don’t. Or breaking rocks. Ever tried breaking rocks? No? More enjoyable than you could possibly imagine. Or strangling chickens. Could be work – could be leisure. For me, leisure, but who knows? Each to their own. Sex. For me, work, but again, some people like to relax like that. You see which way we’re moving here, little Bettina? Work is another one of these primitive ideas. People used to think everything was made up of earth, air, fire and water, and now we know everything is made up of little atoms too tiny to worry about. Everything is smooth. People used to think life was made up of work and leisure but now we know there’s only life. So what do we have now? You’ve lived your whole life to get the things you want. This is like x equals x equals y, right, so let’s strip it down to this: your whole life for the things you want. Are you following me?

I think so, said Bettina.

X equals y, so y equals x, so what do we end up with?

The things I want for my whole life, said Bettina.

Excellent! said Jack. And now, with your permission, sweet Bettster, the Demon-O-Stration.

The salesman reached inside his jacket and pulled out a small box. He opened it and took out a porcelain ornament, a grey and white gull with a yellow beak. He held it up and stared at it. A screen of tiredness dimmed his face, as if he had lent his own sleep and peace to generations against his will and had been reminded he would never get them back.

That comes later, he said sadly, and put the box away. His face filled with energy. He took out a black notebook computer two inches thick and a foot square. He flipped it open, flung out three spindly legs, unfolded the screen till it was a yard across and unhooked speakers which inflated with a spurt of gas to the size of cupboards. Digging in his trouser pocket, he produced a handful of black spheres like squash balls which he tossed in the air so that they hit the ceiling cornice, where they stuck and split open to shine bright spotlights onto Bettina. The theme from Chariots of Fire began to play. Jack took Polaroid pictures of Bettina and fed them into a slot in the computer while the music got louder and the spotlights spun. The lights roamed over her. The lights were bright and warm, almost material, almost moist, as if she was being licked by the tip of an enormous tongue. She closed her eyes.

Jack started to speak but she couldn’t make out what he was saying over the sound of the music, or so it seemed to begin with, until she realised that she’d heard what he was saying a few minutes earlier. After a while, she could remember his words a few hours earlier, and so it went on, his words soaking deeper into the sponge of her memory until she was sodden with reminiscences of his advice and wisdom from her earliest years; advice on fashion, on savings and investments, on home improvements, on what to do with her pocket money, on food and wines, on holidays. She opened her eyes and saw her face reflected in the computer screen as if in a mirror. Her face and the reflected face moved towards each other, swivelled and merged, and Bettina’s mind expanded and stretched thin and taut like the skin of a balloon, so immense that it seemed perfectly flat. Pasted on the inner surface was her life, visible all at once, the baby Bettina waving her fat lacy forearms and fingers across the reaches of the inner space to the wedded Bettina, and the first period Bettina running to the bathroom with her heart beating so strong and hot and indestructible and opposite her on the far side of the sphere the old Bettina yet to come with cold dry soft skin and a stick, and all the Bettinas in between, sleeping, running, crying, laughing, eating, kissing, talking, moment by moment – eight billion Bettinas, one for every quarter-second. The Bettinas were naked and alone with each other. They filled the vault with a sound like starlings in the trees at evening.

The space dimmed and flickered and the starlingsong became an anxious murmur speckled with screams. Something dark and huge moved softly, powerfully across the Bettinas, like a velvet-sleeved roadroller crushing a sea of bubblewrap. In the wake of the strokes the crusher painted through the billions, the Bettinas became fewer and larger and more distinct. Gold, silver and diamonds flashed from their wrists, their necks, their arms and their fingers. They gained tights, panties, bras, blouses, skirts, jeans and sweaters. There were ankle boots, knee boots, fur-lined boots, trainers, stilettos, Chinese slippers, brogues, hiking boots, wellies. The Bettinas were fewer and fewer and wearing coats, fake fur, wool, a broad-shouldered belted raincoat. Rugs unfurled, a dozen televisions, two dozen radios, three cars, four suites, beds, curtains, Hoovers, washing machines, a stack of books and a mountain of glossy magazines. A rattle of pans piling up against the cookers and a river of wine, gin, Martini, cider, Perrier, milk and fruit juice burst from the ovens. There was an avalanche of potatoes, spaghetti, tomatoes, bread, cabbage and a mudslide of chocolate and cheese. Then silence and stillness. Bettina was singular, and alone with her goods in a tightening, darkening inner cosmos. She sat down in an armchair, put her arms out around two of the five washing machines she would possess in her life and drew them close to her.

And just in case you’re still not sure you’ve made the right choice, said Jack, here’s a little something to put your mind at rest: a brand new Samsung microwave, absolutely free*.

Bettina looked up at the ceiling. The lights had gone and the sun of a December afternoon came through the windows. The carriage clock on the mantelpiece chimed 3.15. A dove strummed its crop in the eaves. Jack was tucking the computer away in his pocket. The new microwave waited on the coffee table. Jack stood at the door. He handed her a series of pastel-coloured folders.

All the information you need is in here, he said, opening one of the folders and flicking through the pages, each of which was signed by Bettina. You’ve got Life, our Retrospective-Perspective Material-Amatory All-Activity-Inclusive Time Endowment Plan, with the optional SuperLife Bonus, and the Post-Life Redemption Unit Lump Annuity.

Explain the last part again, said Bettina.

Bettina, said Jack, cocking his head slightly to one side, slanting his eyebrows and putting his hand on his stomach, then his shoulder, then the right side of his chest, then the left side: Hand on my heart. I’ll spend as long as it takes with you. Once more: with Life, you build up units backdated to the beginning of the scheme which after a certain time you begin exchanging for food, goods, property, pleasure, ornaments and accessories – don’t forget the accessories! – until you’re ready to acquire the Post-Life Annuity. The beauty of the Plan is that however much or little you’ve got in the way of goods when the time comes for the Post-Life Redemption, it doesn’t matter – you just hand it all over, pick up your Annuity and go on your merry way.

Where? said Bettina.

Oh, Bettina, said Jack, smiling. He reached out to her, snapped a loose thread from her dress, knelt down, picked an earwig up off the floor, swiftly wove the thread into a harness for the insect and began swinging it from his forefinger. Bettina! Where? I’m sure you began planning that a long, long time ago. There can only be one place, can’t there.

The south of Spain, said Bettina.

Yes! said Jack, laughing loudly. That’s it. The south of Spain! The deep, deep south! He sighed, wiped tears from his eyes and hiccuped. Must be gone, Bettina. I’ve seen the Tullimandies and the Foredeans. No-one else in this neck of the pinetops, is there? He laughed again and went out the door, trapezing the earwig into his mouth.

Bettina heard the salesman’s engine belch and roar and the car take off. She walked to the kitchen.

He must have missed the Museum of Doubt, she said, hoisting the rubbish bag out of the pedal bin. She opened the back door.

The Museum of what? said Jack. His face had reddened, darker than the crimson of the sun going down behind Hill of Eye, and his hair had thickened – not the amount of hair, but the glossy black hairs themselves had fattened out.

Of Doubt, said Bettina. It’s up the road, beyond Mains of Steel. The lassie put the sign up a few years ago after she moved in. You see her coming down with her rucksack to catch the bus for her messages. She bids you the time of day and that’s it.

Jack hunched into his suit. His shoulderblades rose up and his neck telescoped in, his chin tucked into his collar. He looked around, sniffing the air. Dark, he said. Mains of Steel. There’ll be snow. The deer’ll come down to feed. I can’t call by night. Do you have a room?

Of course.

Bless you, Bettling. I’ll get my things.

Jack went through the house, marched out the front door, whistled and clapped his hands. The boot of the car sighed open and Jack moved his luggage upstairs. He had twelve trunks of canvas-covered steel, bound with bamboo. When Bettina knocked later to bring him a towel, she went in and found him in a leather armchair by the fire, dressed in a green velvet dressing gown, typing out a letter with a triple carbon copy on a Cambodian typewriter balanced on his lap. Some of the trunks sat half-open, upended on the floor, exposing bookshelves stacked with scrolls in tasselled leather cases and the scored, mutilated spines of handcopied books. Over the fireplace there were stuffed trophy heads of beasts: a two-headed Friesian calf, a poodle with a forked tongue and a fox which had suffered from Proteus Syndrome.

You’ve made yourself cosy, I see, said Bettina. Would you like some dinner?

I’ll step out for something to eat later, thank you, said Jack.

You won’t find much within ten miles of here.

I’ll find what I need, said Jack.

Later Bettina woke up in darkness. She heard a snap, like a stick being broken, the sound of something heavy being dragged, and the squeak of shoes in snow. The alarm said five am. She went back to sleep. At seven she went downstairs. Jack was already at the breakfast table, picking his teeth with a horn toothpick. He picked up a purse from a pile at his elbow and handed it to her. It was soft deerskin, roughly but well-stitched, branded with the legend A Present From Pinetops.

Thank you very much, she said. Did you cut yourself shaving?

Oh dear, said Jack, burnishing a steel teapot with the sleeve of his blazer and examining his face in it. There is a little blood.

It’s all round your mouth, said Bettina.

Don’t worry, said Jack. It’s not my own. I’m a messy eater. He took out a white handkerchief embroidered with the family tree of the Hohenzollerns, spat on it, dabbed the blood off, stuffed the handkerchief into the teapot and poured himself a cup.

Bettina offered him bacon and eggs and porridge. He shook his head and pulled a sheaf of laminated menus from inside his jacket. Breakfast at Pinetops, they said on the front. Bettina skimmed through.

Consumer Confidence Breakfast – £4.99 Ten Thick Rashers Of Prime Smoked Elgin Bacon Cooked To Your Order On A Sesame Seed Bun With Five Norfolk Turkey Eggs, Hash Browns, Onion Rings, Jumbo Aberdeen Angus Fried Slice, Traditional Scotch Donut Scones, Mashed Cyprus Tatties And A Choice Of Relishes – Finish One Adult Serving, Get Another One Free!

Protestant Work Ethic Breakfast – £4.99 Sixteen Hand-Picked Ocean Fresh Atlantic Kippers In An Orgy Of Pre-Softened Irish Dairy Butter, Tormented By A Treble Serving Of Farm Pure Whipped Cream, On A Bed Of Two Toasted Whole French-Style Loaves, Garnished With Watercress, In A Crispy Deep Fried Eagle-Size Potato Nest – Too Much To Eat, Or Your Money Back!

Wealth Of Nations Breakfast – £4.99 American Style Waffles With Maple Syrup, One Pound Prime Cut Alice Springs Kangaroo Steak, Airline Fresh Oriental Style Fruit Plate With Guava, Pineapple And Passion Fruit, Pinetops Special Chocolate Filled Croissants In Rich Orange Sauce, Whole Boiled Ostrich Egg With Whole Baguette Soldiers, Plus Your Choice Of Celebrity Malt Whisky Flavoured Porridges. Includes Vomitarium Voucher, Redeemable For Second Serving Once Stamped.

I don’t have these things, said Bettina.

Look in your chest freezers, said Jack.

I don’t have a chest freezer, said Bettina.

Look in your kitchen, said Jack.

Bettina went into the kitchen. It had been rearranged to incorporate several chest freezers with transparent lids, piled with frozen pre-prepared breakfasts, shrinkwrapped on trays, complete with disposable plates, cups, napkins and cutlery. In one of the freezers Bettina found a severed deer’s head, complete with antlers. She took it out and dropped it into the pedal bin. The antlers stuck out and stopped the lid from closing. She went back into the breakfast room. Jack was gone.

The snow, a couple of inches, was melting on the road as it got light and the car left sharp black tracks. The branches of the sycamores lining the road were outlined in sticky snow, notched with the thaw. Beyond the farm buildings at Mains of Steel there were no more trees. After the sign reading Museum of Doubt the road climbed into the hills, the temperature dropped and there were heavy drifts. Old Tullimandy came out of the farmhouse when Jack drove past. He shouted and waved his arms. Jack drove on. Tullimandy trotted across the yard to where there was a view of the road and saw a black square, the roof of Jack’s car, speeding through the four foot drifts. It reminded him of the doctor’s computer cartoon of how his blocked artery would be cleared and he felt a pain in his chest. He walked carefully back to the house. Just as well he’d signed up for Life.

The Museum of Doubt was a low whitewashed cottage on the bare hillside with two sash windows and a slate roof. The roof was the same colour as the rocks and scree that stuck out of the snow further up the hill. There were no trees, no walls and no fences. The house had no television aerial. Coal smoke came from the chimney and one of the windows shone with electric light. Jack stopped the car so that the bonnet and the windscreen poked out of the last big snowdrift at the top of the road. He opened the sunroof and climbed out of it. The sun came round the ridge and Jack put on a pair of sunglasses. He went up and knocked on the blue-painted wooden door, under a plastic nameplate which said: The Museum Of Doubt.

She was built like a boy who grows up by the river and has nothing else to do except swim in it. She was thin and fit without being powerful or muscular. Her white face and neck came up out of a Prussian blue sweater thick as a rug and she wore black jeans and old brown moccasins. She had straight copper-coloured hair, cut short neatly. Her eyes listened to what he said but her mouth was blind.

I want to give you a demonstration, he said, sliding his foot over the threshold, stroking the bottom of the door with the tip of his shoe.

Of what? she said, opening the door wide and standing with her hands resting on the doorframe.

Of what you need, he said.

I don’t know what I need.

Then I’ve come to the right place.

No no no, said the woman, shaking her head, keeping her hands against the doorframe, shifting her weight. I don’t mean: I know I need something but I don’t know what it is. I mean: I don’t know what I need, all the time. I’m incapable of knowing what I need, or whether I need anything. I’m not sure I do. It’s my condition.

Eh? said Jack.

My husband used to say that when I tried to explain. I used to ask him why he needed things. He’d say it wasn’t always a question of needing. He’d say, supposing the folk at the British Museum started saying Do we really need all these Egyptian mummies? And they’d say We may want them but I doubt we need them. So they’d throw them out. And then it’d be What do we want with these duelling pistols and snuffboxes and Etruscan vases? What’s the point? You could never be sure you needed any of it. And all you’d be left with would be empty galleries and you’d have to call it the Museum of Doubt.

Jack stared at her for a while, took off his glasses and showed his teeth in a smile. Jack, he said. I’m Jack.

You’re a salesman, said the woman.

That’s an ugly word, said Jack. Let’s forget about selling for a while. I’ll tell you what I’ve come about. Here’s what troubles me. The world is out of harmony. The equilibrium of the cosmos is disturbed. Look at this, now.

He took a set of bronze jeweller’s scales out of his jacket and dangled them in the air in front of the woman.

This is the universe, he said.

He burrowed in his trouser pocket. His fingers dropped two pieces of lead shot onto one scale and four pieces onto the other. The scales dipped.

You see, one side has more than it needs. It’s burdened down with possessions. The spirit is heavy. It’s falling. But the other side has a lack of material things, the possessions it needs to embrace the world. It’s flying away. It’s vanishing. It’s hardly there at all, there’s so little to it. There’s something missing, something it needs. Now watch carefully.

Jack lifted one of the pieces of shot and dropped it in the other pan. The snow deadened the chime. The scales teetered and levelled.

There, said Jack. Harmony. Is that not good? Is that not desirable? There should always be harmony. The side that has too much should always be giving to the side that has too little. Is that not right? The harmony is for ever. And this – he quickly swapped pieces of shot between the pans and waggled his fingers – this is a detail, a process. It could be a revolution. It could be a gift. It could be a sale. It’s over quickly.

I told you already, said the woman. I don’t need anything.

I can show you what you need, said Jack. I can see it. What we have here, between your house and the boot of my car, is a classic disbalance. You don’t have enough, and I’ve got so much. You wouldn’t want to be reponsible for violating cosmic harmony, would you?

No, said the woman. Here’s what I mean. She took the scales from him and tilted them so the shot fell into the snow at their feet. She held the scales up in front of his eyes. Look, she said. No goods. Perfect harmony. She handed the scales back, went inside and closed the door.

Jack laughed, turned and walked a few feet away from the house. He knelt to scoop up a handful of snow and kneaded it in his hand. It fizzed, crackled and steamed. He smeared it over his face and shook his head violently from side to side like a dog which has come out of the sea. He ran back to the house and rapped on the window with his knuckles.

Adela! he shouted. Let me see the museum! I want to buy a ticket!

The door opened and the woman stood in the doorway as before. Jack stepped away from the window.

How did you know my name? said Adela.

It was written on your genes, said Jack, unsteadily. He sounded drunk.

Adela looked down at her trousers.

In invisible … ink. Jack’s eyeballs had turned almost white and he was swaying.

Are you OK? said Adela, moving a pace towards him. His face had turned the same colour as the snow-covered hills behind his head.

Help me, said Jack, sinking to his knees. His body convulsed with coughing and drops of blood sprayed from his mouth. He fell forward onto the ground and twisted onto his back.

Adela went over and knelt beside him, chewing her lip. She pressed her head between her hands.

Cold, whispered Jack. Help me.

Adela took the shoulders of his jacket in her fists and dragged his body over the threshold of her house into the hall. She closed the door. Jack began to cough again. A spurt of blood came out of one corner of his mouth. His lips parted and what appeared to be a tonguetip made of horn appeared.

Huming imma hroat, said Jack. Pu-i-ou. He dry-retched and the horn jerked a little further out. Adela saw his tongue flapping hopelessly against it.

Adela reached down and tugged the piece of horn gently. It yielded. She pulled harder and the antler slid out of Jack’s mouth like the drumstick of an overcooked chicken, along with the attached deer’s head. Adela flinched and she dropped the head onto the floor. She took a step back, swung her leg and delivered all her force to the head through the toe of her moccasin. The head leaped from the hall, out through the doorway and into the sky, spinning into a mighty curve, the antlers humming as they scratched the air. She never heard it fall. She slammed the door shut and turned round. Jack was gone.

She found him standing in the kitchen holding a cardboard box. He wasn’t coughing any more and there was no more blood around his mouth. His face was dead of movement. He didn’t blink. His eyes were big, black and blank, liquid, without subtlety, like the deer’s.

You’re better, she said.

This is for you, he said, holding the box out towards her.

We’ve been there already, said Adela. There’s no need here.

I see need. I don’t see anything here except need, said Jack. Deep within his still face an expression stirred, like a big fish far below the surface of an old lake. He began to fold the box in on itself, punching in the lid, folding down the sides until it was flat, then folding it in half over and over again until it was small enough to put in his pocket. He smiled and spread his arms out wide. His fingers fluttered in space. Adela, you’re lovely, but somewhere along the way you’ve forgotten what life is about. An empty house like this one means an empty life.

No, said Adela. You have to leave.

Adela, said Jack. Listen to me, Adela. Maybe if I say it out loud it’ll start to sink in: you haven’t got a fridge.

The house had a kitchen, a bedroom and a bathroom. It had five pieces of furniture: a sofabed, a chair, a cupboard, a kitchen table and a stool. There was one cup, one plate, one bowl, one knife, one fork, one spoon, and one pan. There was a two-ring gas cooker. There was a drawer of clothes, another of bedding, and five books. The walls and ceilings were bare white and the floor was covered in linoleum which’d been supposed to look like varnished wood when it was new.

There aren’t any prizes for living like this, said Jack.

Living like what?

A failure. You’re suffering from PRAS. Post-religious asceticism syndrome. You think that by not having any possessions your soul becomes purified and you become a saintly being, superior to people who buy glossy magazines and furniture and collect records. That’s great. That’s what Pol Pot thought. The truth is the consumers are the virtuous ones. They express their love for life and for each other and for humanity by buying. That’s how the world becomes a richer place, full of colours. The ones who go out and shop, they’re the real noble spirits of the universe. They understand how ugly their lives would be if they didn’t buy homes and fill them with wonderful goods. You’ve got to own things, Adela, as many things as possible. It’s not a question of being poor. The fewer things you own, the less human you are, and the harder it is for you or anyone else to understand whether you’ve got a life at all.

I wish you’d leave, said Adela.

Jack’s head lolled. He lurched forward and sideways, found the stool and sat down on it. He put his elbows on the table and rested his head in his hands.

I’m still not a hundred per cent, he said. Can you get me some tea?

I haven’t much tea left, said Adela.

Jack pushed the heels of his hands up into his cheekbones, looked at her from under his eyebrows and laughed, a tiny, wriggling, greedy laugh, like the body of a worm kinking through a salad. Then he sat up straight, folded his hands pentitently on his lap, found the laugh and killed it. He blinked, sniffed and pinched his nose.

I see, he said.

I’ve got enough for myself. I didn’t ask you to come in.

Yes, of course, said Jack. I’m sorry. It was selfish of me to ask. I’ve behaved badly today. You can’t forgive me, of course, I don’t expect you to. Please – give me a moment, and I’ll leave.

I didn’t––

Please. Don’t speak: it’s my fault: I provoked you. A minute to collect my thoughts.

They remained like that in the kitchen for a long time, Jack sitting upright on the stool with his hands on his lap, head inclined slightly, gazing at the skirting board, Adela standing watching him in the kitchen doorway, resting her weight on one leg, gently rubbing the tips of her thumbs and index fingers together. There was no sound: no birdsong, no music, no engine, no clockwork, no running water, no wind. When Jack began to cry, Adela heard the tears moving, a noise like dust slipping down a shallow slope of brass. Jack’s back bent and his shoulders shook and he clenched his praying hands between his thighs.

Don’t do this, said Adela softly.

Tears dripped from Jack’s jaw and he rocked to and fro. His voice came lost from a roofed-in maze inside him. All the years, it said. All the days. All the hours. When Adela heard the words a memory of a dream she had never had came into her mind. There was a statue of Jack in the desert, up to his calves in blowing sand. The statue was made of soft, porous stone, deeply scored by the wind and the rain. Jack’s face was slashed with parallel diagonal lines and pocked with air bubbles. His hands were outstretched, perhaps offering some gift, but the gift had long since worn away and he looked like a leper appealing for help. Around him millions of figures wrapped from head to foot in twisted black rags were hurrying across the dunes, the cloths streaming in the wind. They carried smoking buckets of fine sand which they would dip into the ground to replenish, without stopping. Every so often one of the figures would fall and not get up, the drifting sand covering them.

Adela went to the clothes drawer, fetched a white cotton handkerchief and offered it to Jack, who took it and pressed it to his face with both hands. Adela sat on the edge of the table, looking out through the window.

My husband was in sales, she said. That was what he said to other people about what he did. It was what he told me the first time we met but he was looking at me in such a way that I thought about sailing ships. I’m in sales, he said, and I thought of him standing up in the rigging of a sailing ship with three masts and a hundred white sails, all hoisted and full in the wind, and all because of me. It was like Are you happy? Happy? I’m in sails! What he meant was he sold car components. He never said that. He said I’m in sales. Like trouble. Or debt. Or love.

I was waitressing in the daytime and clubbing at night. I had friends, good people. I was dead happy half the time. The only thing was I could never take the happiness home with me and enjoy it later, by myself, whenever I felt like it. It seemed simple enough when you had it but it wasn’t, it was complicated happiness, it had too many ingredients, the people I needed, the places I went, the right sounds, the right drugs. I did a little dealing myself and I met some people who helped me out, I turned into a restaurant manager, and I got a mortgage on a basement flat with a garden in a city. That was a change. It was painted and varnished and all the rooms were empty. I walked in the first day with an ornament I’d just bought and put it on the mantelpiece. It made the place look even emptier and I took a couple of days off work and broke the limit on all the plastic I could get. I got furniture, rugs, candlesticks, scatter cushions, little boxes. I had a passion for the little boxes. I had brass ones, teak ones, birch bark ones, laquered Japanese ones. None of them had anything in them. I wanted all the empty space I had hidden in pretty enclosures. And there were so many candlesticks. Of course I had to get matching candles to go with them.

One time I realised I hadn’t seen one of my best friends for a long time. We’d known each other for years, slept together a few times. I thought about it and decided I hadn’t seen him since I bought this monster bronze coffee table with a verdegris effect. I hadn’t missed him, either.

I was in a big pileup on the motorway in the fog. You couldn’t see the bonnet of your own car in front of you and we were all tanking along at fifty. There were three dozen cars and trucks went into each other. The cars at the front caught fire but I was close to the back and I stayed in my seat, hands on the wheel, watching the lights flashing at me on the dashboard with that ticking sound they make, listening to the screams and shouts from the fires up ahead. I turned the volume control on the radio to try to make them quieter. A man with a bare chest knocked at my window. He was covered in blood and oil and dirt and he was carrying a handful of cotton strips he’d torn from his shirt to make bandages. He asked if I was OK. He was going to be my husband.

He drove me home later in my car. I asked him to. I liked him. I could see he liked me. He told me he was in sales. I didn’t say much. I was in shock because my car was damaged and when it happened I realised that since I’d bought it, I hadn’t once gone clubbing, and it didn’t hurt.

I loved him. I loved him much too much. I loved him like dying of cancer. He didn’t feel the same. He was a good man and he loved me like a favourite dog. I mean he was really fond of dogs. But he never had one while we were together. For him it would have been like polygamy.

He was a collector, he was an enthusiast, he hoarded facts and gadgets. He collected Marvel comics, Motown records and Laurel and Hardy films on video. He had to have them all. Carpentry was another thing. He got very good at that though he never made anything we needed. He kept adding extensions to the bird table. He called it the bird table of Babel. One day, he said, the god of birds would get angry with his work and destroy it.

There was this time I tried to sit down with him and explain the way things were. I told him about how I’d replaced one of my best friends with a coffee table and swapped going out clubbing for a car. I told him how all the nice things we had in the kitchen, the copper pans and the sky blue crockery, how they were taking up space where other things used to be, a walk, a date, a sky. And he said he knew what I meant, you change as you get older, your possessions get a hold on you, and you need to own more things to be satisfied. And I said well that wasn’t exactly what I was meaning, I meant that love and owning things and having a good time were all spaced out along the same spectrum and you couldn’t take it all in at once so you tuned in to different parts and right now I was just tuned in to him. He was like a radio station that played one song and all I wanted to do was listen to it over and over again.

And he said I know what you mean.

And I said Do you?

And he said Yes, even though it’s irritating for other people and they can’t stand it, all you want is the same thing over and over again. I’ve got all the Laurel & Hardy films on video but the only one I watch is Sons of the Desert.

And I said So what’s the point of having all the others.

And he said It’s the complete set.

And I said But you don’t need the others if you only watch one.

And he said I like having the collection. I like having it there. It makes me feel complete.

And I said So you don’t know what I mean.

I came back from the restaurant without a job after I tore up the menus and started asking the customers why they ate so much when they weren’t hungry. I began taking things to charity shops. First the candles, then the candlesticks, the boxes and the scatter cushions. It was a while before my husband noticed and when he did I said we don’t need them. I decided we didn’t need the pictures, the plants, most of the kitchen equipment and the gardening stuff. It was only when I took the TV and video away that he got angry. When I told him we didn’t need them he said there was more to life than need. He was a salesman, of course, like you. He said I was ill. That was a bad day. It wasn’t as if I gave the electrical stuff away for nothing. It got easier after that. I managed to get rid of his records and his comics. I thought he was going to kill me then, although there wasn’t much left in the house to do it with. What are you so upset for? I said to him. You didn’t need any of that stuff. You’ve still got me.

He left that night, after calling me a Jesuit, communist, Big Brother, fanatic, hermit, freak, nun, prude, evangelist, sanctimonious killjoy, Calvinist and bore. I said I loved him and asked if he really needed that other wristwatch? He said is there anything you need? I said I need you, and I took his hand and put it down inside my pants. He said I was a sex-mad Puritan who ought to be put away. He took what he could load into his car and left. It took me weeks to empty the house and sell up to get enough to buy this place and live on. The last thing I got rid of was that ornament I put on the mantelpiece. Then I was ready to open the Museum of Doubt.

Jack had stopped crying. He was sitting with his shoulders still bowed, looking up at her, listening. He looked younger. His eyes were full of wonder and attention, like a child at the theatre, and his face had a cast of wisdom without experience. You’re right, he said.

Adela smiled out of one corner of her mouth. I’ve convinced you, have I, she said, looking out of the window.

I was always convinced, said Jack. It only needed someone to say it. I don’t have to ask how you live without music. You listen to yourself instead. You read the same five books over and over again. The world in daylight is your television.

You’re making me sound like a mad hermit. I am a hermit. I’m not mad, though.

Jack frowned and stood up. I’m wondering whether we really need this stool, he said. He sat on the floor with his back against the wall.

The floor’s cold, said Adela. I don’t like to be uncomfortable. I thought you were a salesman?

I was until today.

What happened?

I met you.

Adela sat down on the stool, leaned her elbow on the table and looked down at Jack. Not so funny, she said.

When I began to sell, it was good. It was paradise. It was my calling. I never thought of it as making money. The money thing was an obstacle in the way of me handing out gifts to people. I’ve walked and ridden and driven the roads for a time. For a long time. I’ve seen the clients’ homes get bigger to make space for the things I gave them. The homes are brighter now, especially the kitchens. I brought those small, dark homes so much light, space and music. I brought them so many cameras, so many motors, so much food. Why did it take so long for me to understand they didn’t really need it? Nobody turned me away before you did.

First you make me out to be a hermit, now you’re turning me into some kind of preacher, said Adela. I just live this way. I don’t care who else does.

A second sun put its head above the ground and ducked back. Yellow light splashed Adela’s skin, cycling to orange and red. A hammer of air cracked the glass of the window in half with a single vertical line and the Museum of Doubt trembled.

You car’s just exploded, said Adela.

They went to the doorway. There wasn’t much left. There were no flames. The frame smoked for a few moments and then the smoke blew away, like a blown-out candle. The frame and the wheels collapsed inwards into a neat pile.

Propane gas canisters and that line of self-igniting chemical heaters, said Jack, shaking his head.

It began to snow, rubbing white into the black star burned in the night’s fall. Jack walked to the nest of entwined metal, reached his hand into its oil-roasted depths and pulled out a new toothbrush in a cardboard and cellophane box. It was all he could save. By the time they went back inside, there was a snowstorm.

Adela lit the fire in the bedroom and they sat on the sofabed, watching it.

I could walk down the hill tonight, said Jack.

Best not to, said Adela.

I was wondering what I’d need to open a branch of your museum.

What you wouldn’t need.

Yes. But after I got rid of everything I wasn’t sure I needed, what would be left.

Adela looked away from the fire and turned to him. What would be?

Jack reached into his pocket and held out the toothbrush.

Adela smiled. Is that it? I think maybe you must be planning to stop in someone else’s museum.

Jack raised his eyebrows. Look, he said, beckoning Adela to move closer and examine the toothbrush. It had a blue plastic handle and white plastic filaments. The word Colgate was written on it.

Look, he said again, when she was next to him, looking down at the toothbrush, held in his two outspread hands like an offering. When you eat, you use the brush to spear the food – he gripped it brush-end up and made a downward stabbing motion – spindle it, or brush it towards your mouth. When you sit down, you use it to brush the ground clean. When you want something to read, you use the word Colgate as an index for the things you know by heart. C is the Code Napoleon, O is Orlando Furioso, L is for Little Lord Fauntleroy. That’s the way it goes.

You can’t sleep under your toothbrush when it’s snowing, said Adela. What do you do then?

You hold it up in front of you like this, said Jack, go and knock on the door of somebody you know, and ask for help.

Adela laughed, looked away and looked back into his face, still smiling. She stayed where she was, close to him.

You didn’t have to call it a museum, said Jack. You must have been wanting people to come. You don’t doubt you need visitors, do you?

No, said Adela, shaking her head. Her eyes were deep and bright and looking into his, where she was falling from altitude towards an unlit continent, self-eclipsed, falling and knowing nothing of the forest canopy about to catch her, only certain it was warm and filled with prey.

D’you know what I need?

Maybe I do. I don’t know what I need but I know what I feel like.

Jack reached out an index finger and placed it between her lips. Adela opened her mouth a little and stroked the finger moist in a pout. A message of salt travelled into her and the answer was raw hunger. She closed her eyes, the moon rose and she was high with longing to wound a creature. She opened and closed her jaws and pressed her teeth into the finger, wanting to meet bone, wanting the knuckle to break. She felt blood run down her chin and the hunger stopped. She opened her eyes and saw Jack’s head hung back, his finger unharmed and unmarked. There was no blood.

Oh, your finger, she said. She took it in one warm fist and squeezed it, kissed the tip. I didn’t mean to hurt you. I wanted to bite your finger off but I didn’t want to hurt you.

Jack raised his head. You didn’t hurt me any more than I wanted to be hurt, he said. Stand up.

Adela got up and Jack unfastened her jeans and took them down. He touched her vagina with his lips and looked up at her. I’d like to fuck you with my tongue, he said.

Yeah, go ahead, said Adela.

When they were tired they lay overlapped on the sofa facing each other, boy-thigh girl-thigh boy-thigh girl-thigh, elbows propping them up at either end.

I’m in sails, said Jack. With an ‘i’.

What is it you sell? said Adela.

I sell as much as anyone can ever get.

And how much does that cost?

It doesn’t cost anything. It’s just Life.

I don’t get it.

Life. Guaranteed to last a lifetime. All you can eat, all you can drink and all you can wear before you die.

But you’d get that anyway.

Would you? You haven’t.

I haven’t got life? Do I not seem alive to you? You thought I was alive enough when you cried my name a minute ago.

Jack looked away. His body slackened and tensed and his face closed, as if he was preparing to reshoulder an intolerable load after a moment’s rest. He said: You are alive. You’ll die one day like all the rest but you never got what they call a life. That’s what they’ve got, life. But you’ll live till you die. It’s not the same. You’re alive.

Adela shook her head. D’you want something to eat?

Jack shook his head. You can’t spare it.

There’s soup. You’ll have to have some.

Only if you let me pay.

Don’t be stupid.

Here, said Jack. He reached into his jacket and took out a small box. He held it out to Adela. This survived. Take it. For the soup.

Adela looked at the box for a while. OK, she said. She got up, put on her jeans and sweater, took the box and walked towards the kitchen.

Adela, said Jack. What was that last ornament you got rid of when you left your old place?

A gull. A grey and white porcelain gull with a yellow beak.

Some time later Adela went to call Jack through for the soup. He was gone. She looked in the morning for his tracks in the snow, but they had been covered up by the freshly fallen.

She opened the box and took out a grey and white porcelain gull with a yellow beak. She went up behind the house to the tall rocks, laid the gull on a flat place, took a heavy stone and pounded it to powder. By evening the weather turned and rainclouds crossed the ridge. Rain fell and washed the powdered porcelain off the rock, where it mixed with the melting snow and was carried away to the river on the floor of the glen.

* Subject to availability