Читать книгу Reality by Other Means - James Morrow - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

An Audience with the Abyss

James Morrow’s Short Fiction

GARY K. WOLFE

At the 1999 International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts — the most eclectic of the various academic conferences dealing with science fiction and fantasy — a panel discussion on the work of James Morrow drew such interest that it became the basis for a special Morrow issue of the academic journal Paradoxa: Studies in World Literary Genres. The impressive list of contributors included writers as well as critics — Samuel R. Delany, Michael Bishop, Élisabeth Vonarburg, Michael Swanwick, Brian Stableford, and F. Brett Cox among them — and the journal has since devoted only one other issue to a single fiction writer, Ursula K. Le Guin. As insightful and brilliant as some of the essays were, they also occasionally indulged in that favorite critical game of connect-the-dots. In trying to situate Morrow’s unique satirical voice, the essayists came up with a dizzying list of possible influences, analogues, and sheer wild guesses — Swift, Voltaire, Twain, and Vonnegut most often, but also Philip K. Dick, Robert Sheckley, Chaucer, Dostoevsky, Kafka, J.G. Ballard, Donald Barthelme, Nathaniel Hawthorne, John Irving, Ray Bradbury, Anatole France, Evelyn Waugh, and for good measure, Nietzsche and maybe Heidegger. And all this before Morrow had written The Last Witchfinder, possibly his most complex and rewarding novel, or The Philosopher’s Apprentice, or his delightful pop-culture fables Shambling Towards Hiroshima and The Madonna and the Starship, or Galápagos Regained, or more than two-thirds of the stories in the present collection.

One of the more bizarre of many bizarre sketches from the Monty Python troupe — whose sense of absurd juxtapositions is not entirely incongruent with Morrow’s own — involved the ridiculously militaristic “Confuse-a-Cat” service, designed to rouse bored and mopey cats from their torpor. Since the beginning of his fiction career in the 1980s, Morrow has been cheerfully providing such a service for readers of science fiction and fantasy, and increasingly for a much broader readership in such literary journals as Conjunctions. The earliest story here, “Bible Stories for Adults, No. 17: The Deluge,” immediately throws us off balance simply by virtue of its central character: what on earth is a prostitute named Sheila, a self-described “drunkard, thief, self-abortionist … and sexual deviant,” doing on Noah’s ark, let alone completely undermining Yahweh’s scheme for the redemption of the human race — which scheme, as she points out, is really nothing more than simple eugenics? The range of deliberate anachronisms, from Sheila’s allusion to a nineteenth-century pseudoscience to her apparent knowledge of how to freeze sperm for later fertilization, was startling enough — and maybe just science-fictional enough — to earn Morrow his first Nebula Award in 1989. (Interestingly, Morrow returns to a very secularized version of Noah’s ark in “The Raft of the Titanic,” in which the crew and passengers save themselves by constructing a huge platform which becomes their home and eventually an independent nation, choosing to forgo rejoining the world altogether after learning of the madness of the First World War.)

“The Deluge” was one of a sharply satirical series of “Bible Stories for Adults” that Morrow published between 1988 and 1994 (another included here, “Bible Stories for Adults, No. 31: The Covenant,” hilariously deconstructs the Ten Commandments). Together with his “Godhead” trilogy of novels (Towing Jehovah, 1994; Blameless in Abaddon, 1996; The Eternal Footman, 1999), these stories helped establish Morrow’s reputation as science fiction’s premier religious satirist. It was a role that science fiction readers, who often felt besieged by the same forces of irrationality that were Morrow’s targets, embraced with enthusiasm.

Science fiction had grappled with religion before, of course, but often in simplistic or sentimental ways. C.S. Lewis appropriated the machinery of the genre to construct heavily didactic Christian parables in his Out of the Silent Planet trilogy (much as he abducted the machinery of fantasy for his Narnia novels), while Ray Bradbury’s story “The Man” used an elusive but thuddingly obvious Christ figure to construct a similar fable of warm faith vs. cold science. Monasticism is treated as a preserver of learning in the post-apocalyptic world of Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, but the novel eventually turns on a church-vs.-state controversy and a familiar critique of self-destructive materialist culture. A few novels, such as James Blish’s A Case of Conscience and Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, sought to engage a more complex interaction between faith and belief, good and evil, while fewer would take on the church itself as a cause of dystopia, as in Lester del Rey’s little-known The Eleventh Commandment, and fewer still, like David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus, would openly condemn the pernicious effects of belief itself. And, of course, Vonnegut had his Bokononism. But more often than not, when science fiction turned to religion, the results were uneasy fictions of accommodation, often featuring sensitive and intelligent Jesuit priests puzzling over mysterious aliens and intractable moral conundra. (Perhaps because of their intellectual traditions, Jesuits have long been favored by science fiction writers, who have seemed much more reluctant to take on, for example, Southern Baptists.)

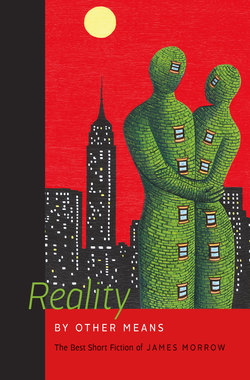

Here, though, came James Morrow, unequivocal atheist, cheerfully profane fabulist, witty scourge of nincompoop theodicies — the one storyteller who could somehow make logical positivism play out like a battlefield exploit and revealed religion like a Marx Brothers movie. Morrow neither apologized for his humanist stance nor retreated into a clever but facile nihilism (as would sometimes happen with Vonnegut, the author to whom he is most often compared). Morrow would not only proclaim the death of God, but show us his massive corpse being towed across the Atlantic like a dead whale. Readers will find no shortage of such religious satire in Reality by Other Means, from the Church extending its right-to-life doctrine to protect the rights of the “unconceived” in “Auspicious Eggs” to the tiny Martian invaders who decide to conduct their own religion-vs.-reason ideological war on the streets of Manhattan (since they simply don’t have room on the small Martian moons where they now reside). Appropriately, the only ones who know how to deal with the Martians are lunatics.

But focusing narrowly on Morrow’s religious satire risks overlooking the considerably broader scope of his work — he’s impatient with all sorts of dogma, the dogmas of academia not excluded — or the significant ways in which he has helped to expand the scope of what science fiction can do. Morrow’s relation to science fiction is an interesting one, and not entirely unconflicted. On the one hand, he has long held, as he did in an interview with Samuel R. Delany in that Paradoxa issue, that science is “the best way we have of obtaining knowledge about the outside universe: provisional, tentative, vulnerable knowledge, to be sure, but still astonishingly substantive,” and his fiction reveals a deep understanding of scientific thinking from Newton (see The Last Witchfinder) to Darwin (see Galápagos Regained) to current physics.

On the other hand, he is far from being a “hard SF” writer, and he doesn’t hesitate to employ pulp pseudosciences when the story at hand calls for them; the magical “Infusion D,” which turns already degenerate men into something like Neanderthals in “Lady Witherspoon’s Solution,” might well have been concocted by Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll, and Dr. Jekyll himself very nearly makes an appearance in the form of Dr. Pollifex in “The Cat’s Pajamas,” with his equally magical “QZ-11-4” substance, which somehow turns beast-men into successful local politicians by multiplying their capacity for empathy (don’t ask; just read the story). There’s also more than a touch of Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau in that tale, but tracing the various ways in which Morrow adapts and reshapes tropes from earlier science fiction might well precipitate another essay altogether. The “science” of vibratology in “The Iron Shroud” is an equally unlikely but ingenious construction of a credible-sounding Victorian pseudoscience (the prolific British paperback author Lionel Fanthorpe also imagined such a science). In “Daughter Earth,” Morrow moves beyond imaginary pseudoscience and fully in the direction of surrealism, as a mother gives birth to a miniature Earth, a global biosphere complete with oceans and a rapidly accelerated pattern of evolution (the extinction of the dinosaurs somehow becomes a moving family tragedy weirdly reminiscent of Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth), while in “Spinoza’s Golem” he moves in the direction of Jewish legend — though this particular golem is actually a kind of steampunk robot which “lives not by magic but by springs and cogs, ratchets and escapements.”

There is also some familiar furniture from science fiction and horror in “The Vampires of Paradox,” which could almost be viewed as Morrow’s answer to Arthur C. Clarke’s famous story “The Nine Billion Names of God,” only in this case it’s a philosophy professor specializing in paradoxes, rather than a computer scientist, whose visit to a remote monastery turns out to alter the fate of the world. Clarke, who often wrote himself into corners that he could only get out of by resorting to a mysticism he didn’t actually believe in, is a good representative of the kind of rhetorical paradoxes in science fiction that Morrow exploits, and “The Vampires of Paradox” brings these to the foreground, beginning with a catalogue of often familiar verbal paradoxes and expanding its scope to include Fermi’s paradox (regarding the apparent absence of other civilizations in the universe) and Schrödinger’s cat (the famous illustration of quantum superposition). Both are among the favorite puzzles of science fiction writers, and Morrow’s examination of them is ingenious — but the story also has its improbable pulp features, such as the roach-like alien “cacos” who feed on paradoxes and attach themselves to humans like Robert Heinlein’s puppet masters, or the Poe-like “tarn” that oozes through a “crack in the lithosphere” and threatens to inundate the world.

Morrow rarely employs anything resembling traditional hard science fiction extrapolation, but in “Martyrs of the Upshot Knothole” — my candidate for the most gnomic story title here — he has done enough historical and scientific research to make almost convincing the longstanding rumor that one of the massive nuclear bomb tests of the 1950s (called “Upshot Knothole,” which helps make sense of the title) took place just near enough to a downwind movie location for the actors and crew to suffer radiation-induced cancers years later. The movie in question is an actual John Wayne epic, The Conqueror, and Wayne himself, who shows up as a central character, may have been among the “martyrs.”

This brings us to another fascinating but seldom discussed aspect of Morrow’s fiction: his enthusiasm for popular culture, movies and television in particular, and bad movies and television in even more particular. His decision to invoke The Conqueror — widely remembered as one of the most egregiously misconceived movies of the 1950s, with John Wayne as a wildly unlikely Genghis Khan — suggests that Morrow’s fascination with (and considerable knowledge of) film is not exactly limited to the classics. Caltiki, the amoeba-like monster that the epistemological explorers encounter toward the end of “Fixing the Abyss,” is borrowed from an actual 1959 Italian horror film, Caltiki, the Immortal Monster, to which the story’s narrator, himself a third-rate horror director, has made a number of knock-off sequels. And when the same explorers encounter Kafka’s Gregor Samsa in his giant-insect form, the narrator thinks of the 1954 monster movie Them! The narrator of “The Wisdom of the Skin” is likewise a filmmaker, reduced to boring educational films of the sort that haunted high school students in the 1950s, while the yeti who decides to study with the Dalai Lama in “Bigfoot and the Bodhisattva” displays an encyclopedic knowledge of Abominable Snowman movies, partly due to his having eaten the brain of a dying NYU film-studies professor who was trying to climb Mount Everest. This same yeti forms an attachment with the Dalai Lama over their mutual fondness for James Bond films, and the oddly Buddhist-sounding titles of some of them (Tomorrow Never Dies, The World Is Not Enough, et cetera).

Nor will Morrow hesitate to employ a pop-movie cliché when it suits his purposes, sometimes inverting the cliché as a means of underlining his own satirical agenda. “The Cat’s Pajamas” ends with a classic scene of enraged villagers storming the mad scientist’s lair, but these villagers are a more eclectic group than they might at first seem: “the mob included not only yahoos armed with torches but also conservatives gripped by fear, moderates transfixed by cynicism, liberals in the pay of the status quo, libertarians acting out anti-government fantasies, and a few random anarchists looking for a good time.” This comes after the beast-folk, having ingested that unlikely empathy drug, have nearly transformed the local government into a compassionate liberal democracy. “Whatever their conflicting allegiances,” the narrator goes on to note, “the vigilantes stood united in their realization that André Pollifex, sane scientist, was about to unleash a reign of enlightenment on Greenbriar. They were having none of it.” The stereotypical mad scientist, in other words, is seen as mad simply by virtue of his being sane, and Morrow uses the familiar figure as a way of skewering no less than six different ideological positions in one sentence. As I mentioned earlier, uncritical dogma, no matter what its ideology, is like catnip to Morrow’s imagination.

Playing with such clichés, conventions, and rhetorical reversals is one of the key techniques by which the author consistently reminds us that we are in a James Morrow tale, no matter how familiar its outward lineaments may at first appear. One of the most elegantly constructed stories here, “Arms and the Woman,” which revisits Helen of Troy, is packed with such techniques. Its very opening line is a reversed cliché: “What did you do in the war, Mommy?” “Mommy” is Helen herself, telling her children her own version of the Trojan War in a frame-tale (another technique that Morrow often uses). Appropriately enough, Morrow sprinkles the story with Homeric epithets — “horse-loving Thebaios,” “brainy Panthoos, mighty Paris, invincible Hector” — but soon the epithets themselves go wonky and anachronistic, as poor “slug-witted Ajax” becomes “slow-synapsed Ajax.” When we first meet Helen and Paris, they are a bickering middle-aged couple who might as well be in a Howard Hawks comedy. Helen, stuck at home, keeps trying to find out what the war is about, while Paris keeps telling her “Don’t you worry your pretty little head about it.” He complains about her weight and graying hair and suggests that, with a combination of ox blood and river silt, “You can dye your silver hairs back to auburn. A Grecian formula.” Then, before taking her to bed, he slips on “a sheep-gut condom, the brand with the plumed and helmeted soldier on the box.”

Do such pointed and punning allusions to contemporary consumer products yank us out of the classical mise-en-scène in which we thought this story was located? Of course they do: they are reminders that we are in Morrow-space, as are such deliberately self-referential lines as Paris later saying “I’m sorry I’ve been so judgmental” or Helen herself, after figuring out a way to end the war, described as “a face to sheathe a thousand swords.” But the most important use of such self-referential anachronisms comes near the story’s moral center, after the “slow-synapsed Ajax” expresses doubt as to why the war should continue after Helen has volunteered to return to her husband. “Because we’re kicking off Western Civilization here, that’s why,” responds an outraged Panthoos. “The longer we can keep this affair going — the longer we can sustain such an ambiguous enterprise — the more valuable and significant it becomes.” “By rising to this rare and precious occasion,” adds Nestor, “we shall open the way for wars of religion, wars of manifest destiny — any equivocal cause you care to name.” The story, it turns out, recasts the most famous war of classical antiquity as a deliberate boondoggle born of masculinist fantasies of self-esteem — the invention of the idea of war itself — with Helen, taking charge of her own destiny, as the spoiler. It is arguably the most overtly feminist tale in this book, even without mentioning Helen’s confrontation with the automaton of her younger self, built to replace her on the parapets as motivation for the soldiers, or her retirement to Lesbos, whose economy involves trading olives in order to import “over a thousand liters of frozen semen annually” — thus accounting for the children who are listening to the story in the frame-tale. It’s an historical fantasia, but nearly becomes science fiction when it needs to. Genre, for Morrow, is at best a suggestion.

Frame-tales, journal entries, and false documents are narrative techniques common both to Morrow and to earlier science fiction. In “Spinoza’s Golem,” for example, the fictional Spinoza’s own account of building a golem is framed by a contemporary museum curator’s efforts to rediscover it, while “Lady Witherspoon’s Solution,” set in a post-Darwinian Victorian England, is another frame-tale with a distinctly feminist undercurrent. A scientific expedition in the Indian Ocean comes across a remote island populated by what the captain concludes to be a race of peaceful Neanderthals, apparently spared the “normal pressures that, by the theories of Mr. Darwin, tend to drive a race towards either oblivion or adaptive transmutation.” But there are, curiously, no females among the tribe. Befriending one of its members, the captain is led to the grave of an Englishwoman, Kitty Glover, and shown her journal, which reveals a different sort of tale altogether. Kitty, well born but reduced to the workhouse, comes under the tutelage of the eponymous Lady Witherspoon, whose “Hampstead Ladies Croquet Club and Benevolent Society” disguises a far darker secret. In terms of literary dissonance, the story begins as a persuasive redaction of the lost-race tale, segues into a Dickensian fable of redemption and charity, and then turns — at least for a moment — into a bizarre Victorian rendition of something like Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, as Lady Witherspoon stages periodic fight-to-the-death battles between men — most richly deserving a stern comeuppance — who have been “devolved” through the mysterious counter-evolutionary serum “Infusion D.” These are the creatures who, when their usefulness to Witherspoon’s entertainments has been exhausted, are shipped off to the Indian Ocean to form what appeared to be the Neanderthal society in the framing story. When Lady Witherspoon asks her protégé if she would agree that “there is something profoundly unwell about the [male] gender as a whole, a demon impulse that inclines men to inflict physical harm on their fellow beings, women particularly,” Kitty responds, “I have suffered the slings of male entitlement,” among which, clearly, is sexual assault.

Given stories like these, it should hardly be surprising that Morrow’s trenchant skewering of all forms of intolerant or merely muddled thinking — together with his erudition concerning philosophy, history, science, and even those bad movies — have made him a favorite among liberal intellectuals and academics. At the same time, however, he occasionally reminds us that he is hardly pandering to our comfort zones, and that herding behavior is not restricted to Victorian patriarchs, religious fundamentalists, or sensationalist media. “Fixing the Abyss,” perhaps the most wildly freewheeling tale here in terms of its plethora of satirical targets, begins with knowledgeable allusions to Martin Heidegger and Jean Baudrillard, then quickly focuses on the potentially dire consequences of academic groupthink. When a mysterious and growing chasm opens on the Penn State campus, threatening all of central Pennsylvania, the narrator suggests that the causes include a resurgence in fundamentalist thinking, a revived international arms race, “the institutionalization of clerical rape, and the aestheticization of suicide bombing” — but argues that the immediate trigger was a lecture by a comparative literature professor who believes that “morality, truth, beauty, and knowledge are illusory notions at best, overthrown in the previous century by perspectivism, relativism, hermeneutics, and France.” “It’s all very well for a scorched-earth, skepticism-squared ethos to enrapture Ivy League humanities departments,” the narrator (the horror-film director) muses, “but when épistémologie noire comes to America’s land-grant universities, we know we’re all in a lot of trouble.”

Almost a commonplace in science fiction criticism is the idea of “literalization of metaphor,” probably first suggested by Samuel R. Delany and later adopted by such equally distinguished writers and critics as Ursula K. Le Guin, in which a figure of speech that would be read as metaphorical in normal discourse can be a statement of literal fact in a science fiction text (one of Le Guin’s examples is “I’m just not human until I’ve had my coffee”). In reality, it’s almost impossible to find examples of such sentences in science fiction narratives, and one could as easily argue that any form of fantastic literature does the same thing (“He’s a nice guy during the day, but a beast at night” could apply to any number of werewolf tales). In Morrow’s fiction, though, we can actually see something like this literalization happening. The epigraph for “Fixing the Abyss” is a quotation from Heidegger: “Language speaks. If we let ourselves fall into the abyss denoted by this sentence, we do not go tumbling into emptiness. We fall upward, to a height. Its loftiness opens up a depth.” In the world of the story, that abyss becomes quite literal, and the equally literal ways in which the world responds to it grow increasingly absurd. If the rift was caused by a kind of critical mass of nihilism, might it not be neutralized, as chemical compounds can neutralize each other, by inundating it with sentimentality? So the first strategy is to dump into the abyss “countless Smurfs and Care Bears, … wheelbarrow loads of garden gnomes, Charles Dickens novels, and Mother’s Day cards, along with ten thousand emergency DVD transfers of Shirley Temple movies.” In other words, literalized metaphors are used to fight a literalized metaphor. When that and a more conventional military expedition fail, “a team of crack nihilists” is recruited, including the film-director narrator, a metal hurlant rock singer, a playwright, and an avant-garde mathematician. Their quest turns into an almost slapstick katabasis, a classical journey to the underworld, only one in which the usual fearsome gatekeepers are replaced by Friedrich Nietzsche, Kafka’s Gregor Samsa (in his insect form), and a financial-derivatives swindler named Roscoe Prudhomme. Finally, they reach the god-like Caltiki — a monstrous amoeba, who congratulates them on having “proven yourselves worthy of an audience with the abyss.” The primordial roots of that abyss, the monster explains, can be traced to “the single worst idea your human race has ever devised.”

And just what is that terrifyingly dumb idea? Again — read the story. Simply by holding Reality by Other Means in your hands, you have proven yourselves worthy of your own audience with the abyss, and it’s quite an interview.