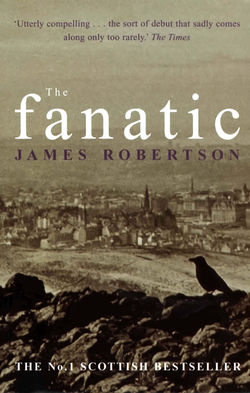

Читать книгу The Fanatic - James Robertson - Страница 12

Edinburgh, April 1677

ОглавлениеSir Andrew Ramsay, Lord Abbotshall, till lately Lord Provost of Edinburgh, considered leaving his long, luxurious wig on the stand where he had placed it earlier, while looking over his accounts. It was a very fine wig, thick and lavishly curled, but it made his head hot and got in the way when he was trying to read. Still, he did not really like to be seen without it; he was approaching sixty, and the wig gave his large face a dignity it otherwise lacked. Without his expensive clothes and headpiece he might have been taken for a publican or a shopkeeper. Not that Sir Andrew had anything against publicans and shopkeepers; on the contrary, he was their prince. Or, at least, he once had been.

He was expecting his son-in-law and although John Lauder was family, Sir Andrew still liked to impress his formidable personality upon the younger man. He stood up, took the wig and, in front of a mirror, carefully lowered it onto his head. He laid the ends of it over his ample shoulders and briefly admired himself, large, sedate and solemn in the glass. That was his style in these times of wild ranters and gaunt rebels. Some might think him fat and graceless, but he saw himself as a dancing-master; nobody could jouk and birl like Sir Andrew Ramsay when it came to politics. He was the great survivor. ‘Andra, ye’re a richt continuum,’ a friend had recently told him. And there was no better evidence of his political brilliance than the fact that, over three decades of war, religious upheaval and governments of utterly different complexions, he had become progressively and irresistibly more and more rich.

He cleared his throat with a grumble of self-approval, and sat back down to his books, his dreams of political intrigue, and his decanter of brandy. He was a merchant, the godfather of the city’s trade, and a laird with extensive properties in Fife and Haddingtonshire. He had served as provost under two regimes, first during the Commonwealth and then after the Restoration, when it suited the new government to install someone with a proven record, rather than trust to the vagaries of council elections. Once he had consolidated a power base on the council, elections were reintroduced and proceeded without alarm. Sir Andrew managed to remain Lord Provost year after year as if, like some portly extension of the royal prerogative, he had been restored to a throne of his own.

Being a man with his own interests at heart he was as amenable to receiving bribes as he was adept at making them. He’d had a knighthood from King Charles, which discreetly obscured the one he’d received from the usurper Oliver Cromwell. Other honours accrued like interest. He was a Member of Parliament, Privy Counsellor and Commissioner of Exchequer. In 1671 he had achieved a further triumph: he was made a judge, an appointment for which he had no merit and only one qualification. His patron Lauderdale, the Secretary of State for Scotland, had raised him to the bench as Lord Abbotshall, although they both despised the law’s proclaimed adherence to that kittle principle, justice. That was the qualification.

It was not a bad record of worldly achievement but there was no doubt about it: what Sir Andrew called management and his enemies called corruption was an exhausting business, and he was no longer young. For years he’d stayed one step ahead of the pack, cajoling here, wheedling there, showing a palm of gold one minute and a fist of iron the next. Sometimes he could be charm itself in the council chambers; other times he would blow in like a gale, driving all opposition before him. Once he’d even had to organise a riot in the street outside the council windows to emphasise his opinion. After twelve successful elections to the provostship, Sir Andrew had had just about enough of Edinburgh.

And then, too, there had been the strained relationship with the Duke of Lauderdale, who’d been breathing down his neck on account of complaints about the competence, even the legality, of some of his decisions in the Court of Session. Finally, three years ago, Lauderdale had suggested that it was time to pull his finger from the fat pie of provostry, that his short stay on the bench must also come to an end, and that he should spend more time with his family at Kirkcaldy. The provost demurred. Lauderdale insisted, and Sir Andrew reluctantly resigned.

But as his glory days were fading, he liked nothing better than to recount them, to anybody who would listen. His son-in-law, John Lauder, who owed him much in terms of placement and preferment, usually had no option but to lend an ear. It was a source of satisfaction to Sir Andrew to have a lawyer on the receiving end of his reminiscences: as a judge he had been deaved with lawyers’ arguments long enough in court, and their contempt for his ignorance was only matched by his hatred of their souple-tongued smugness.

Not that John was by any means the worst. That prize would have to go to his cousins the John Eleises, father and son. The father was in his sixties now, and not so active, but the son was even more offensive, a subversive do-gooder who seemed to show no fear of his betters in arguing against them in favour of outed ministers, rebels and witches. It was Eleis who, with his mentor Sir George Lockhart, had been a ringleader of the advocates in 1674, when forty-nine of them had been debarred from practising because they dared to insist that they could appeal to parliament against decisions made by the Lords of Session, in spite of a royal edict forbidding it. Sir Andrew, though he had by then resigned from the bench, had been outraged by the presumption of these meddling pleaders.

He could not abide the younger Eleis, who had even dragged John Lauder into the advocates’ dispute. John had foolishly stood on a principle as one of the forty-nine, and had been banished out of town to Haddington for more than a year until a compromise was reached: without sufficient advocates, the procedures of the courts ground almost to a halt, and the forty-nine were grudgingly readmitted.

It was a great misfortune that John Lauder was infatuated with Eleis’s devotion to the principles and process of law: it had got him into trouble and would do so again. Nevertheless, Sir Andrew was fond of his daughter’s husband. He and Janet had been married nine years and provided him with five grandchildren to date. Lauder was only thirty, an open-minded, modest man who could yet be moulded.

The Lauders stayed in the Lawnmarket, a stone’s throw from the courts. Sir Andrew’s residence in town was also at the upper end of the hill, but it was not the power-house it had once been. He still made huge amounts of money from various bits of business, and his accounts showed that the Toun itself owed him nearly two thousand pounds in rents and other debts, but he was no longer the driving-force of municipal commerce and enterprise, and folk no longer queued for an audience with him. More and more, he was taking Lauderdale’s advice and spending time at Abbotshall, across the Firth and away from the scenes of his past triumphs. A visit from his son-in-law, then, was not unwelcome, although it was fairly unusual. Their relationship was easy enough but there would always lie between them the shoogling-bog of their differences regarding the law. It was something they stepped around as a rule, to avoid an embarrassing slip on either side; especially on Sir Andrew’s, since he had been so very bad at law and John was very good.

Today however it was John who was on the uncertain ground. He had come with a set of questions anent the Bass Rock and the black dogs that lay in it. He had been down in East Lothian often, sometimes visiting the Ramsay policies at Wauchton, and of course all the while he was in exile at Haddington the coast had been just a short ride away. He had seen the Bass stark in the great grey sea, but had not ventured across to it. The tide or the winds had always conspired against him. Now he was wondering about a trip to view the prison: ‘Would my lord Lauderdale object tae my gaein ower, dae ye think? I wouldna want tae gie offence by speirin if it was only tae be refusit.’

‘Whit for are ye wantin tae gang tae the Bass, John?’ said Sir Andrew. ‘The place is a midden o zealots. Ye’re no seekin business frae ony o them, are ye?’

‘Their business wi the coorts is by wi, I think,’ said Lauder. ‘But I would like tae see the place. It’s a curiosity.’

‘It certainly is. But ye micht no be wise tae disembark there, John. There’s a touch o the rebel aboot ye, as I mind. Yince they had ye in the Bass, they micht no want tae let ye back hame again.’

It was a kind of joke, but he neither laughed nor smiled as he made it. He noted that his son-in-law was at least sensible enough to show some humility in response.

‘I hae learned a lesson frae the advocates’ affair, my lord. I canna pretend that we dinna differ on that maitter, but I am mair inclined tae compromise these days. I’d hae thocht that would be enough tae distinguish me frae the recusants and guarantee my return tae North Berwick.’

It was an even drier joke than Sir Andrew’s. The older man grumphed.

‘Weill, ye’re probably richt. But it’s a grievous dull place, John. There’s naethin there but solans and sneevillers.’ He reached for the decanter of brandy, refilled his own glass and poured one for Lauder.

‘I’m tellt the birds are in such numbers that they’re a marvel o nature, my lord. I would like tae see that, tae step amang them.’ He cleared his throat. ‘And mebbe, if I was there, I would tak anither keek at this fellow Mitchel, that’s been the cause o such grief tae the Privy Cooncil. He’s the only yin that still has a chairge hingin ower his heid, I think. Aw the rest has been convictit.’

‘Mitchel,’ said Sir Andrew, his brow lowering. ‘A vile and dangerous fanatic if iver there was yin.’

‘Aye,’ said Lauder. ‘That’s whit I would like tae see – the worst kind o fanatic. There was hardly onybody got tae see him aw the years he lay in the Tolbooth, as ye ken. But I would like tae see him noo, him and Prophet Peden and the ithers. They hae a kind of philosophic interest tae me.’

‘Ye philosophise ower much for yer ain guid, John. Ye may gang tae study Mitchel, but be assured he will study you harder. He will mark yer face in his een and yer words in his lugs and if ye dinna come up tae his impossible mark – which ye’ll no, no bein a Gallowa Whig or an Ayrshire rebel – and he should iver win free o that place – which he’ll no, if guid coonsels prevail, unless it’s tae mak a journey tae the end o a short tow – he’ll seek ye oot wi his pistols jist as sune as he’s fired a better shot at his grace the Archbishop. Stay awa frae him, and ye’ll no run that danger. Ye can dae nae guid there, and he can dae ye hairm.’

‘His leg is destroyed by the boots, my lord, and his brain is hauf gane as weill, by whit I hear. He’s no fit tae hairm onybody but himsel.’

‘A wild beast is maist dangerous when it’s caged,’ said Sir Andrew. He had picked up his glass, and now, staring hard at Lauder, he brought it to his lips. He took a long, slow mouthful of brandy, the stare never shifting as the stem of the glass rose. With his round drink-bludgeoned face it might have been the blank look of a soft-brained bully, but the eyes were cold and hard like a bird’s, and the large hooked nose was a bird’s beak. He looked as though he had spotted something shiny in the dirt.

‘Speakin o beasts,’ he said, after swallowing noisily, ‘wasna Mitchel an associate o that auld hypocrite Thomas Weir? Perhaps it would be interestin, eftir aw, tae see if he shared ony o his, eh, recreational tastes.’

‘I imagine that connection’s been explored,’ Lauder said, ‘by His Majesty’s law officers. Onywey, Weir’s been deid seiven year noo. There’ll be naethin tae discover there, I doot.’

Sir Andrew regarded his son-in-law gravely. ‘Ye had a terrible affection for Weir’s sister, gin I mind richt. That’s whit vexes me aboot ye whiles, John. Ye will get ower close tae bad company. Fanatics, witches …’

‘I was hardly close tae Jean Weir,’ Lauder said, his face reddening. ‘I didna ken her at aw. I felt sorry for her. It was a bad business awthegither.’

‘Major Weir the yaudswyver,’ Sir Andrew mused. ‘Dae ye mind we visited him in the Tolbooth? No a bonnie sicht … Even you wi yer odd sympathies, John, I think would find it no possible tae imagine hoo onybody could get pleisure oot o carnal relations wi a horse.’

‘We’re gettin waunert, my lord,’ Lauder said.

But Sir Andrew was enjoying himself. ‘In fact,’ he said, ‘hoo exactly dae ye manage it wi a muckle craitur like a horse? Ye could mebbe ask Mitchel if he kens. Dae ye get it tae lie doon, or whit? And when it’s doon, hoo dae ye persuade it no tae get up again when it sees ye approachin wi yer dreid weapon furth o its scawbart? Or mebbe ye let the beast staun, and approach it wi a ladder. It’s a mystery, is it no, John?’

Lauder smiled, to show that he was not too strait-laced to appreciate his father-in-law’s humour. ‘Aboot the Bass …’

‘The Bass is nae langer mine tae say ye can or ye canna gang ower,’ said Sir Andrew. ‘That’s Lauderdale’s domain noo. Ma advice tae ye’s this: bide in Edinburgh. Leavin it’s nae guid for ye unless there’s plague.’

‘I thocht,’ said John Lauder, ‘that wi yer auld interest in the Bass ye micht hae speired o his lordship for me.’

‘He’s the Secretary o State, laddie. He’s mair important maitters tae occupy him than issuin warrands tae would-be philosophers. Onywey, we’re no sae chief as yince we were.’

‘That may be true, my lord,’ Lauder said, ‘but surely it was by yer ain guid offices that the Bass fell intae his hauns? Athoot yersel, he wouldna hae it noo as a prison for the rebels.’

Sir Andrew sat back, wiping his mouth. ‘Ye dinna want tae hear that auld tale again, surely?’ But Lauder sat back too, nodding, while Sir Andrew, who could never resist reliving one of his greatest coups, stroked the tresses of his wig and got into his stride.

‘Lauderdale owed me a favour. It’s peyed noo, that’s the difficulty. The Bass Rock was yin hauf o the bargain atween us, and the tither … weill, the tither was the port o Leith.

‘Ye would only hae been nine or ten, John, so ye’ll no mind this, but when Cromwell occupied us in the fifties, he fullt the port o Leith wi English and had a muckle fortress biggit there, a citadel they cried it, the object being baith tae hae English sodgers watchin ower us and tae set the place up as a tradin rival tae oor ain guid burgh.’

‘Ye can still see bits o the stanework doon there,’ Lauder said encouragingly.

‘Aye, but they’re scant, for it was maistly made o turf. Onywey, the English settlers wantit the port freed frae Edinburgh’s grup, a thing that would hae had the maist grievous repercussions on oor finances. I hadna been a twalmonth in ma first term as provost, but I could see the only wey tae retain oor superiority ower Leith was tae invest in it. Cromwell’s commander in Scotland was General Monk. I had the Cooncil gie five thoosan pund tae the construction o the citadel, and that satisfied Monk – I think he could see Cromwell wasna lang for the warld, and that mebbe it would be silly tae lose aw favour wi us for the sake o a wheen English brewers and glessblawers. Sae naethin changed, and of coorse as sune as the young King wan hame at the Restoration the citadel was ordered tae be dismolished.

‘But noo comes Lauderdale, His Majesty’s new Secretary o State, upon the scene. He’d managed tae get the site o the citadel gien intae his chairge. He was fain o the auld plan and got a charter o regality tae raise Leith intae a burgh. It was a ludicrous notion – hoo could sic a clarty boorach be a burgh? – but Lauderdale had set his mind on it, sae it behooved me tae find a wey roon his plans, jist as I had afore wi Monk, or he would hae broke the trade o Edinburgh. Aw the duties on wines and ale that the Toun levied frae Leith my lord would hae acquired for himsel, and in my capacity as a public servant I couldna let him deprive us o oor richtfu taxes.

‘Sae I says tae him, where’s the sense in fallin oot ower a puckle bawbees? Ye want tae mak a profit oot o Leith – I’ll spare ye the bother o administerin the levies, suppressin corruption amang yer officials and the like. I’ll buy the citadel back frae ye for Edinburgh. And tae compensate ye for the loss o income, I’ll gie ye a lump sum in lieu o the wine imposition. Ye’ll walk awa wi yer pooches fou, my lord, I said, and Edinburgh will keep control o her ain destiny. There’s no mony men that can speak sae free wi Lauderdale nooadays.’

John Lauder acknowledged this with a half-smile. ‘How much was it again,’ he asked, ‘that Lauderdale wanted for being deprived o his livelihood?’

Sir Andrew laughed. ‘Ay, he’s such a puir man! Him wi a hoose in Lunnon and the estate at Thirlestane and land aw ower Scotland. He drave a reasonable bargain, John. Rich men can aye be civil wi each ither. I offered him sax thoosan pund for the citadel, and five thoosan pund for the levies, which was a generous sum, but worth it tae keep my lord sweet – sae he got eleiven thoosan pund aw tellt, no a bad income for nae labour.’

‘The Toun wouldna been happy at peyin oot sic an amount?’

‘The Toun didna hae ony choice,’ said Sir Andrew. ‘I was the Toun in thae days, John. Onywey, haudin the duties in oor grup was my priority. Wi the citizens’ drouth and capacity for liquor, it didna tak lang for the Cooncil tae realise I’d made them a guid niffer.

‘That was awa back in 1662, when the King was newly hame and there were debts and favours fleein aboot the country like a flock o stirlins. Aye, an plenty o scores tae be settled tae, eftir twenty years fechtin an sufferin under the kirk elders. I kept ma heid abune it aw when I couldna keep it ablow the dyke, John, an I advise ye tae dae the same in these troubled days – especially since ye hae Janet an the bairns tae think on tae, an no jist yersel wi yer high notions o the sanctity o law.

‘I held ontae that favour eicht years, and there were times, I confess, when Lauderdale’s position at coort wobbled a wee, when I thocht I michtna get the chance tae redeem it. But then the miscreant tendency began tae stir themsels again, and the government was lookin aboot for a siccar place tae lodge the rebel ministers and keep them awa frae the lugs o the ignorant. That’s when the idea o the Bass insinuated itsel intae ma heid, and I went tae Lauderdale and offered him it. There it was, a muckle lump in the middle o the sea, wi an auld fort upon it – needin some repairs, of coorse – inaccessible but handy enough for Edinburgh, and wha should happen tae be in possession o it? Why, Sir Andrew Ramsay, Lord Provost o Edinburgh, that had gotten it as pairt o the lands o Wauchton frae a puir laird fawn on hard times. I niver would hae thocht the brichtest jewel o that inheritance would be an auld tooth stickin oot in the Firth, but there ye are.

‘I reckoned ma income frae the Rock was nae mair than fifty pund per annum, and that was frae sendin lads ower tae lift the solans’ chicks, but I tellt Lauderdale it could be doubled if there was a permanent garrison pit there, the birds managed on a proper basis, and sundry charges levied on whaiver micht be pit tae live in the place. Hoo muckle would ye want for it, says my lord? Oh, says I, no as muckle as I peyed ye for Leith, it’s only a Rock eftir aw. But, I says, it’s mebbe gotten a hidden value if it keeps the kingdom free o rebels. Oot o Scotland, oot o mind, as it were. Weill, Lauderdale took the hint. I’d been votin his wey in Parliament aw thae eicht years, and takkin maist o the ither burghs wi me forby. Weill, he says, suppose ye live tae be an auld man o ninety, that’s nigh on forty years’ income ye’d be losin. At a hunner pund a year, by your accoont? I’ll ask the King tae gie ye fower thoosan pund for it. And he did, John, he did. Fower thoosan pund,’ he finished hoarsely, pouring himself a fresh brandy, ‘for a lump o rock, a flock o geese and a rickle o stanes that ye wouldna keep pigs in. At that price I didna even fetch back ma sheep – it would hae been ower pernickety, d’ye no think?’

John Lauder could not help admiring his father-in-law’s grotesque self-confidence. He himself was always questioning – his own nature and motives, the accepted norms of daily life, the habits of individuals and of society. But Sir Andrew was like the Bass, a solid relentless rock in a swirling sea of change. He was beholden to him in many ways, certainly he could not afford to offend him, but there were times when he wanted to wring his fat neck. Just now though, he wanted his influence to clear him a passage to the Bass. And there was no motive that Sir Andrew needed to know of, other than the one he had given out loud: he wanted to see James Mitchel, the fanatic to beat all fanatics. He wanted to see what made him what he was.

‘Will ye speak wi the Secretary o State then?’ he asked. ‘He kens me. He kens ma loyalty to the King. I would like to see the prison and cast an objective eye ower prejudice.’

It was a nice touch. Sir Andrew shrugged. ‘John, ye’re a guid lad, though ye whiles keep company I dinna care for. Yer cousin Eleis hasna pit ye up tae this, has he?’

‘This is my concern alane, my lord,’ said John Lauder. ‘John Eleis has naethin tae dae wi it. It’s mair than a week since I last spak wi him.’

‘Then I’ll hae a word,’ said Sir Andrew. Then he seemed to change his mind. ‘In truth, I hardly think it necessary tae fash Lauderdale wi sic a triviality. I can arrange it masel. They are ower lax wi the rebels and permit them parcels o food, letters and visits frae freens and faimly when the boat is sailin. There’ll be nae restrictions, I would think, on an honest leal fellow like yersel.’

Lauder had not told his father-in-law the whole truth. It was correct that he had not seen his cousin John for a week: Eleis had been through in the west, where there was an ongoing outbreak of witchcraft, which had already led to a trial and some executions, and would probably be the excuse for more; he had gone to try to establish who or what was fanning the fire of accusation. But Lauder and he had discussed Mitchel in the past, and they had already arranged to meet later that day. Eleis was due back from Glasgow in the evening, and would meet Lauder at Painton’s shop for some food and drink.

Painton’s shop was half-full, but there was a table in a back-room where they could talk undisturbed over their ale. In fact, Lauder noted with some relief, there was enough noise in the place that they would not be overheard, if their conversation should turn on anything requiring discretion. With his cousin that was always a possibility.

Eleis was full of the witch alarm, which had been dragging on since before the winter. In October Sir George Maxwell of Nether Pollok, a noted anti-government man who had been fined and imprisoned several times for promoting conventicles, had fallen ill, complaining of pains in his side and shoulder, and suffering from terrible night-sweats. Around that time a lassie of thirteen or so, named Jonet Douglas, recently arrived in the area from the north, began to linger around the big house at Pollok. She was deaf and dumb, but managed to attract the attention of Sir George’s three daughters, and told them by means of signs and drawing pictures that she knew what was causing his illness. She persuaded them to send two men with her to a nearby cottage. This was the home of a woman called Jean Mathie, whose son had been locked up some time before for stealing fruit from the Pollok orchard. They entered the cottage, and when the woman’s back was turned, Jonet stuck her hand in at the lum and pulled out a little waxen image wrapped in a linen clout. She gave it to the men who carried it back to the laird’s daughters. The wax figure had two pins stuck in the right side, and another down through the shoulder. They removed these, without saying a word to the patient, their father. That night he slept well again for the first time, without the sweating sickness, and the pains in his body slowly receded.

After a couple of days, when it seemed clear that his recovery would be complete, his daughters told him what had happened. Jean Mathie was arrested and sent, protesting her innocence, to the Paisley tolbooth, where she was pricked for witchmarks, which were found in several places.

‘I am scunnert o the hail] affair,’ said John Eleis. ‘Sir George grew no weill again, as ye mebbe ken, at the start o the year, and you or I would hae pit it doon tae the rheumatics, or creepin age or some such thing. But this Jonet Douglas lass – who, mark this by the way, aw this while canna speak a word but seems tae ken Scots, English, French, Latin and a wheen ither leids when they’re spoken tae her – discovers the auld wife’s son John tae hae made a second doll oot o clay, and when they gang tae the cottage they find it where she tellt them tae look, ablow the bolster in his bed, wi three preens intil it. Noo they had kept the lass back at the door, sae she couldna be said tae hae laid the effigy there hersel, though it seems tae me she could easy hae been there in secret afore, she’s that flittery and daunerin. Sae they cairry John and his wee sister Annabel tae Sir George’s hoose, and tell him whit has occurred. And Sir George begins tae mend again.’

‘Why the sister?’ Lauder asked. ‘Whit was her pairt in it?’

‘Och, the usual thing, ye ken, when ye mix young lassies wi witchcraft. She’s jist aboot ages wi Jonet Douglas, and had a fit o the hysterics, sae they thocht she was possessed. And eftir they had worked on her for a while, of coorse, they discovered that she was possessed.’

‘By Satan?’

‘By a muckle black man wi cloven feet cried Maister Jewel, if ye please. Satan by anither name. Her mither made her lie wi him for the promise o a new coat. And this Maister Jewel had been comin intae see John at nicht tae, throu the windae, wi a rabble o witches at his back, and John kent the witches for his mither and three neibour wifes. He confessed under examination and then aw the weemun were taen and examined and they confessed. Weill, except Jean Mathie, she said she was innocent tae the last. They were aw burnt at Paisley, John and the fower weemun, but the assize spared Annabel, in their mercy and wisdom.’

‘Is it finished then?’ Lauder asked. ‘Or is there mair tae come?’

‘Mair,’ said Eleis. ‘I’ll no deave ye wi the details, but if there’s a witch in aw the west country, it’s the lassie Jonet Douglas. Sir George is seik again, and she’s castin aboot for anither effigy tae find, and I doot she’ll be successfu, for there’s a tide amang the folk that’s cawin her on. Oh, and here’s a thing: she has her voice back. Suddenly she’s able tae speak, and awbody’s bumbazed. She disna ken how she gets the information aboot aw thae witches, she says it jist comes intae her. But no frae the Deil, mind – she has nae correspondence frae him. I wish the doctors would examine her insteid o the folk she accuses – the limmer’s a richt wee miracle o intuition.’

‘She’s a gift tae the folk that want tae hunt witchcraft tae extinction,’ said Lauder. ‘That’s the trouble wi it – ye canna cry the dugs aff yince their bluid’s up.’

‘Oor freen John Prestoun is slaverin at the bit tae be involved,’ said Eleis. ‘If it comes tae a commission, which I doot it must, Prestoun will be hankerin for a place on it.’

‘He aye hankers,’ said Lauder dryly. ‘There’s no an advocate like him for pleadin for himsel. He fell in fast enough wi the royal edict against appeals, and he has the same enthusiasm for findin lanely auld weemun and licht-heidit lassies tae be witches.’

‘I hate these trials,’ said Eleis. ‘I wish I could keep awa frae them. But if I didna plead for the puir craiturs, there’s gey few ithers would – no wi ony conviction, leastweys, for ye canna get a less popular panel than a witch – and the likes o Prestoun would hae a clear road tae drive them tae slauchter. There’s an unpleasant mochness in the air this spring, cousin. That thick feelin afore the thunder breaks. I fear there may be a storm o witchery aboot tae burst upon us.’

‘It may be a fierce summer then,’ said Lauder. ‘Ye’ll ken better than I, but I hear the west is awash wi fanatics forby witches, that they haud their conventicles weekly on the moors, wi thoosans in attendance. Lauderdale’s patience must be near whummelt. He claps the recusant ministers in the jyle, but there aye seems tae be mair tae rise and tak their places.’

‘Like hoodie-craws amang the corn,’ said Eleis. ‘It’s the Archbishop that’s forcin that issue, though. Lauderdale, in himsel, disna care a docken where folk gaither tae worship, if they dinna threaten the stability o the land – that’s ma opinion, though of coorse he could niver say as muckle. But St Andrews sees the field-preachins as a slight tae his ain authority, and has pushed and pushed Lauderdale tae act agin them. Sae the conventiclers cairry weapons tae their prayers noo, and there’s some o them jist ettlin for a chance tae defend their cause frae the dragoons. Noo that’s whit Lauderdale canna thole, for it threatens him, and sae ye’re richt, John, skailt bluid will follow.’