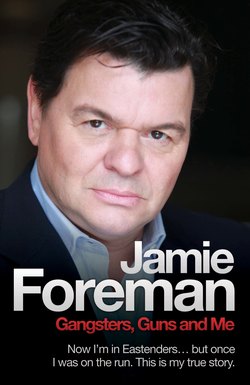

Читать книгу Gangsters, Guns & Me - Now I'm in Eastenders, but once I was on the run. This is my true story - Jamie Foreman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE WAY IT WAS

ОглавлениеI was brought up to be what we call a ‘straight goer’. I was taught to live my life honestly and not to do anything wrong. I was raised to be a good boy. To behave myself at all times and never to take anything that didn’t belong to me.

Yet taking things that didn’t belong to him was exactly what my father went out and did every day. You could call it a moral paradox, but to me it was just the world I was born into. Dad did what he did to put food on our table and clothes on our backs. He did it because he wanted a slice of the good life and he had no other means of getting it. It was what he did; he loved the buzz and that’s the way it was. There are no two ways about it. I come from a criminal background and I can’t say I’m ashamed of it.

I was born the second son of one of London’s most successful gangsters, Freddie Foreman. He had been at it for years before I came along and, wherever he went, his reputation preceded him. For years my dad had been involved in some of Britain’s most audacious armed robberies, and dealing with the most dangerous criminals working in Britain. It was his world, and there was no way my arrival on the scene would change that.

Not that I had much of a clue about what he did. I was just a kid and my dad was, well, just my dad. He might have been out grafting and building his reputation, but it didn’t mean Dad wasn’t there to tuck in his kids at night with a story and a kiss. One of my earliest memories is the rustle of his mohair and silk suit, the faint smell of brandy on his breath, his strong, masculine aftershave and the feeling that I didn’t have a worry in the world. Dad was always there for us. There would come a time when I’d need to be there for him, but that was later. Much later.

‘Us’ was my mum, Maureen, my older brother Gregory and my younger sister Danielle, and, although we moved about a bit when I was young, my childhood really got going in Kennington, South London. We lived in Braun House on the Brandon council estate in a lovely, newly built high-rise flat and, at six years old, I wouldn’t have wanted to be anywhere else in the world.

It sounds like a cliché, but I was born into a time when the indomitable spirit of the British was at its strongest. The adults surrounding me had survived the war and the ensuing austerity. They had seen their neighbourhoods destroyed – there were bombsites on every corner (which made great playgrounds for us kids) – they had run out of food and lost loved ones in the blitzed London streets as well as on foreign fields. Yet they were bonded by values that nowadays are being sadly eroded. There was a marvellous sense of togetherness among the working classes – you didn’t steal from your own, you didn’t hurt your own and, yes, you did leave your front door unlocked. It really did happen, I promise. I remember two old sisters who allowed me and my mates to walk into their flat through the back door and make ourselves a sugar sandwich whenever we pleased. The only rule was that you never went past the kitchen. We never broke that rule, nor did it ever enter our minds to.

In those days, council flats were something to be proud of. All the women used to clean their front steps and the landings, and the only smell on any block was that of Jeyes Fluid. That lovely, clean smell of antiseptic just about summed up how houseproud and respectable most people were back then.

Not that I spent much time around the house. When I wasn’t at Henry Fawcett Primary School, I was mostly off playing with my mates. There was no better place to play than the streets. We’d be out from dawn to dusk, forever inventing new games, fighting new battles. I saw my fair share of fights, but they were mainly between older kids. I could hold my own and was always a good puncher. But I never had a fight with anyone smaller than me. Mind you, there weren’t many people smaller than me.

If it wasn’t Mum calling me in at night, it would be my lovely auntie Nell, a pivotal member of the family. My Nell was a ‘Spitfire’ – small, feisty and beautiful. She looked after me when Mum and Dad needed to keep me ‘at a safe distance’. There’s no denying that Dad’s business meant it was sometimes best if I was temporarily out of harm’s way. But it didn’t bother me one bit – spending time with my Nell and my two beautiful cousins, Barbie and Geraldine, was always a joy. Barbie was like a big sister to me, and I loved her dearly. Nell would take me shopping down Lambeth Walk and then to the pie and mash shop – my favourite. Still is today. She was always fussing over me with the best food she could afford. I remember sitting in her tiny council flat in Lambeth North with her and my other aunts watching the Saturday-afternoon films on BBC2 while they drank tea and smoked cigarettes. You could have cut the smoke with a knife. I just loved sitting there with my gorgeous, indomitable aunts watching A Tree Grows In Brooklyn or some other weepy, and seeing them by turns crying, laughing and gossiping about anything and everyone the films reminded them of. They often talked of the war and, although there were plenty of painful memories, it inspired such awe in me when I saw them laughing the past away together. Those precious afternoons played a huge part in teaching me to laugh in the face of adversity.

Becoming aware of what Dad did, and of his power in the criminal underworld, was a gradual process. I would have had to be blind, deaf and dumb to think that he was a regular man working regular hours in a regular job. However, as a kid, I wasn’t told any more about him than I needed to know. And the truth was, I didn’t need to know much. Not that I wasn’t interested. The older I got, the more fascinated by the mystery of it all I became. As a result I was a sponge for everything that happened around me. It was like being a detective in one of the movies I loved – Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep, say – only the case I was working was my life, and it was anything but dull.

I remember walking with my auntie Nell down Lambeth Walk one day, and a man stopped me in the street. I must have been five or six years old, and I could immediately sense the alert in Nell. She obviously recognised the bloke as one of Dad’s enemies, and immediately created a bit of a brouhaha before stealing me swiftly away. It was incidents like this, combined with my dad’s insistence that I always told him where I was going, that made me realise I had to be on my toes when I was out and about. That is still true today. No one told me I was unsafe – I’m sure Dad always had me covered without telling me – but to certain people the Foremans were a prime target and I was taught not to take anything, or anyone, for granted. It was a valuable lesson that has stayed with me all my life. I developed a sixth sense for smelling a dangerous situation, and it would help me through many a tight spot in the future.

There was plenty more for me to soak up when Dad moved us from our council flat into one of his new businesses, the Prince of Wales public house in Lant Street in the Borough. It was so exciting for a seven-year-old. To say my dad owned a pub was a big step up in my social circle – being the son of the local publican gave me a great degree of kudos with my mates that I have to admit I liked. Of course, there was another side to the enterprise that I was only dimly aware of back then. As well as being a good money earner, the pub was a good front.

It was at the pub that I began to get more of an inkling about who, and what, my father was. Criminal or not, Dad was a man who didn’t take kindly to bad manners. And it soon became clear that, as a landlord, he wouldn’t have these principles trifled with. My mum told me that, soon after we moved in, he had a run-in with the local bully, who obviously didn’t know who my dad was. One day Dad was laughing and joking with some customers at one end of the bar while the bully was playing darts down the other end.

‘Quiet down there,’ said the bully, pointing a finger at my father. ‘Man at the oche.’

Dad glanced up, the smile vanishing from his face. Mum sighed. Something was about to happen, and it wasn’t going to be the start of a beautiful friendship. All the signs were there – Dad was icy cool, calm and collected, with that flicker of anger in his eye. Not great news.

Casually, Dad walked across the pub, past the bully and up to the dartboard, which he ripped from the wall. He opened the door to the pub, walked outside and threw it on to the street. He’d been meaning to get rid of that dartboard, so I suppose this was as good a time as any. It might have ended there, but while my dad was outside the stupid sod who’d started it all decided to shut the pub door and lean on it. He was trying to shut my dad out of his own pub. Mum sighed again. Now there would definitely be trouble.

Dad charged the door, which burst open and sent the bloke flying. Quick as a flash, Dad picked him up, knocked him spark out with one punch and slung him out the door.

‘No more darts in here,’ he said, dusting his hands off before resuming his chat with the customers. Before long, laughter filled the room again.

There was a body and a dartboard in the street. Word soon got around with the locals that Dad wasn’t to be messed with.

The pub quickly became a South London hotspot. Everyone used to go to the Prince of Wales, but they all called it Foreman’s. It was a lovely little place – red flock wallpaper from Sanderson, wood half-panelling on each wall and, on one of them, a beautiful 16th-century map of London. Around the walls hung silhouettes of Dickens characters – Uriah Heep, Mr Bumble, Bill Sykes and Oliver Twist surveyed us all. Dickens was significant because the great man himself had once resided in Lant Street when his father was in Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison just around the corner. The house Dickens lodged in had been demolished, but Dad had acquired its lock and key and proudly displayed it in a glass case. I even attended the local primary school called – you guessed it – Charles Dickens Primary. Little did I know that one day I’d play one of literature’s greatest villains, Bill Sykes, in Roman Polanski’s film of Oliver Twist.

Foreman’s was the first pub in South London to have a wall-mounted jukebox. It played all of the latest releases before they hit the charts, thanks to the A.1 Stores in Walworth Road. They made sure you heard it first in the Prince of Wales. The atmosphere was always electric. It was the kicking-off place for young people’s nights out before heading off to clubs in Herne Hill, Hammersmith, Streatham or the West End. Young ‘faces’ from the manor – the Elephant and Castle, Walworth Road and Bermondsey – would come in with their beautiful girlfriends and the place had a sexual charge that was any young boy’s dream. I’ll never forget how it felt walking through the bar and being grabbed by all these pretty young women who wanted to say hello to little Jamie. By the time I’d crossed the bar I’d have lipstick marks all over me, and I loved it.

Dad’s business extended further than just selling beer, but that didn’t mean it was a pub full of criminals. His ‘firm’ used to congregate there, of course, but they happily rubbed shoulders with the rest of the young crowd. No one needed to know that they were calling in favours and doing a bit of business at the same time. My godfather Buster Edwards and the other Great Train Robbers would often drop by, as would the Krays, who were good friends, especially Charlie and his beautiful wife Dolly. But the customers were none the wiser and the atmosphere was always lively and happy.

My dad and his firm were precisely why Foreman’s had a reputation for being such a safe pub. You could take your girlfriend there and be secure in the knowledge that nobody was going to take liberties with you. No one ever caused any trouble. They didn’t dare. If anyone was about to perform, the chances were they’d be dealt with before it even kicked off and slung out without ceremony – the ‘chaps’ could smell trouble at a thousand yards. Dad’s pitch was always in the corner of the pub, so he could see everything that was going on. As a result, the atmosphere wasn’t tense: it was fantastic.

The sixties were in full swing, and our pub seemed to represent that – it was a melting pot of classes and personalities. Pop stars such as Cat Stevens and Manfred Mann were regulars, as was the great footballer Bobby Moore and his wife, along with other West Ham, Spurs, Millwall and Chelsea stars. Actors and actresses – especially Barbara Windsor and the Carry On team – mixed freely with High Court judges and politicians. A highlight was when the legendary Hollywood star George Raft was in town and spent the day drinking with my mum and dad. Unfortunately, the Home Office deemed Mr Raft unsuitable to stay in the country and he was deported back to the States. I wish I could have met him. Still, I have some great photographs of them together.

All manner of men and women came to the pub and had a great time. Young as I was, I sensed that Dad had extensive connections and interests that went far beyond anything I could fully understand. I was part of it, in as much as I was a Foreman, and I used to feel as if I was linked to something slightly nefarious and secretive. It was exciting and exhilarating, and it made me feel protected and safe.

I observed the kind of network that was growing around my father and I began to understand the reputation he had. Moreover, I learned that a man in that world has nothing but his reputation and his name. The values my dad and his firm adhered to were strong: you never fuck anyone over for money; you never hurt one of your own; you never take liberties with anybody; you never bully and most importantly you never, ever, grass. In those days there was more honour among thieves. And, while I was no thief, I grew up around men whose values I had nothing but respect for.

Everyone accepts and adapts to their surroundings, and that’s what I did as a boy. I can’t condemn anyone I’ve grown up with and loved all my life. My family, my uncles (the men close to me who I call uncles), they were all products of their environment and products of their day. Their lives took them down a certain path, and if they were horrible people I would have recognised it by now. They were strong and dangerous people, yes, but they were also kind, generous and caring men. There were equally strong and dangerous men on the other side of the fence – the firms that were the enemy. That was life, and to me what I experienced as a boy was merely part of London’s rich tapestry.

Crime may have been exciting. It may have meant money and power. It may have been the thing that made my dad feel alive. But Freddie Foreman did not want his son to follow in his footsteps. He wanted better things for me.

Dad and I have always had a special relationship. Behind the scenes he was tender, caring and very keen to educate me and make me think. He never once raised a hand to me – he ruled with the mind, not the rod. When telling me off, he would make me see the error of my ways. He always spoke to me as an adult, and introduced me to adult things – from Beethoven to Buddy Greco, Frank Capra to William Shakespeare. Sure, he’d get down on the floor and play soldiers with me, but he would lay out the battle lines with care, and regale me with stories about tactics and great battles. He stimulated my mind and instilled a love of the theatrical in me.

Dad was simply the best dad he could be. As a child I felt such warmth and love that, when my parents told me I had a place at boarding school, I trusted that it was the right move. And, as always, my trust in them wasn’t misplaced.