Читать книгу Elefant - Jamie Bulloch - Страница 14

9 Zürich 13 June 2016

ОглавлениеSchoch’s hand wasn’t the only one trembling. Around this time almost all of them had difficulty holding their cups in the Morning Sun. It smelled of filter coffee, boozy breath and damp clothes impregnated with smoke. The air was terrible, but if a newcomer stood in the open doorway for a moment, scanning the packed lounge for a free seat, those lucky to already have one would shout, ‘Oi!’ and ‘Close it!’

Most had spent the night outside or in an unheated shelter and were here to warm themselves both externally and internally.

Schoch normally came here to drink his second coffee every morning. He’d have his first at Presto, a shop in a petrol station that opened at six.

But this morning he’d overslept and had come straight to the Morning Sun. He preferred the second cup anyway. You could sit down here and the coffee was better. Although he’d taken a while to get used to the pious sayings that hung on every wall in this small, plain lounge, when facing the choice between pious sayings and expensive coffee, a homeless person didn’t have to think too long about it. Anybody who wanted to could get something to eat here too. But Schoch didn’t want to, not at this time of day. His stomach was still too unreliable. You could never be sure how you were going to react to solid nourishment. He needed to give it time. And a little coffee.

By noon his stomach had sufficiently settled down that he could give it something to eat. Depending on his financial situation he’d have his lunch either at Meeting Point, where people like Schoch came to shower and wash their clothes and could eat for four francs, or at the soup kitchen, where the food was free. If he needed something harder than apple juice to wash down his food, Schoch would dine at AlcOven, a meeting place for drunks, where you could also have a shower and wash your clothes, but were allowed to bring your own beer to accompany a cheap meal.

He usually took dinner at Sixty-Eight, where you could get a decent meal for free, but only in the evenings.

At this early hour – it was just after eight o’clock – most guests at the Morning Sun weren’t particularly chatty. But there were always a few noisy ones, those who’d already taken their first drink of the day. Schoch was one of the silent ones. He never drank before ten. And even when he’d had something to drink he didn’t say much. If he did speak, it was quietly, which lent him an aura of mystery. That and the fact that nobody knew anything about him. Everybody knew the stories of most of the others on the streets, knew what they used to be and what had made them end up here. But they knew nothing about Schoch. One day he just arrived on the scene with old Sumi. The two were inseparable, moved around together and supported each other when they were no longer able to stand up straight.

Supposedly, Schoch was also the one who found Sumi when he snuffed it. He didn’t die from drinking, people said, but from having given up.

Schoch didn’t get close to anyone else afterwards. He kept a friendly distance and remained a mystery.

A young man he’d never seen here before, probably a rejected asylum-seeker needing to go underground, freed up the seat opposite. Within seconds Bolle had sat down. Rapping his knuckles on the table by way of a greeting, he said, ‘Shitty weather.’

Bolle was one of the loud ones. He always had something to say, but it wasn’t always new. Schoch normally avoided him, but in this situation all he could do was acknowledge Bolle’s presence. He shrugged and focused on his cup.

Bolle was blind in one eye, which looked like the white of an undercooked egg. Hence his nickname, Bolle, from the old Berlin folk song: ‘His right eye was missing,/His left one looked like slime./But Bolle being Bolle,/Still had a cracking time.’

Bolle tried to get the attention of the elderly lady, one of the many pious volunteers who helped out here. When she looked over at him, he called out, ‘Coffee schnapps, please!’ He was the only one who laughed; everyone else had heard the joke plenty of times before.

Or they didn’t understand him, like the African man sitting next to him, who said, ‘No German,’ when Bolle, still laughing, repeated, ‘Coffee schnapps,’ and grinned at him.

‘No alcohol,’ Bolle explained in English.

His neighbour replied, ‘No, thank you.’

Bolle now had a laughing fit. ‘No, thank you!’ he repeated. ‘No, thank you!’

When he’d composed himself he turned to Schoch and said, ‘They’ve got a new girl working at Sternen.’

Schoch’s cup was by his lips. Before he took a sip he said, ‘Aren’t you banned from there?’

‘I was,’ Bolle corrected him.

Schoch put his cup back on the table and said in the same dispassionate tone, ‘Because you’ve stopped begging the customers for beer?’

‘Because the new girl doesn’t care. It’s all revenue, she says. Earned, stolen or begged, money is money.’ Once again Bolle had a fit of coughing and laughter combined. ‘Earned, stolen or begged,’ he wheezed.

Schoch failed to react and Bolle tried to change the subject. ‘Ever seen white mice? Not real ones, but in your head.’

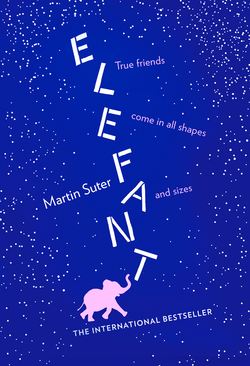

Schoch shook his head. Pink elephants, on the other hand, he thought …

‘I have,’ Bolle continued. ‘Last night.’ His bloated red face suddenly assumed a troubled expression. ‘Do you think that’s a bad sign?’

Schoch wasn’t listening. The memory of the tiny pink elephant had suddenly emerged from nowhere. Had he dreamed it? Or hallucinated?

‘Oi, are you listening?’

‘How do you know they don’t exist?’ Schoch said. He placed a franc on the table for his coffee, got up, rummaged on the rack for his yellow raincoat and left.

‘He’s right,’ Bolle mumbled. ‘How do I know they don’t exist?’