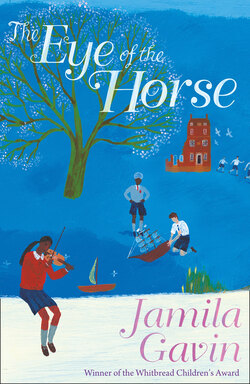

Читать книгу The Eye of the Horse - Jamila Gavin - Страница 11

FIVE The Prisoner

ОглавлениеIt was Saturday. Maeve Singh came downstairs and stood in the doorway of her parents’ flat. Her body was still girlishly thin and undeveloped, as if she had grown up reluctantly. She held herself awkwardly stiff, like a tightly-coiled spring; her lips pressed together, her pretty face taut and defensive.

Her paper-white skin looked almost translucent as the sunlight fell across her face.

She was dressed to go out, though without much effort. She would have looked drab, except that the sun seemed to ignite the coils of red hair, which fell to her shoulders from beneath a panama-shaped green hat, and enriched the otherwise dull brown of her shapeless coat.

Her little daughter, Beryl, stood half-behind her, knee-high, clutching her mother’s coat in one hand, while sucking her thumb through a tight fist, with the other. She wasn’t dressed to go out, and knew that she was about to be left. Her light brown eyes shifted uneasily round the room, settling first on Jaspal, her half-brother. She was frightened of him. He always scowled and looked angry. He didn’t like her, she knew that. He hardly ever looked at her.

Marvinder was different. Beryl loved her. Marvinder seemed pleased to have a sister, even if she was only a half-sister. But Beryl would get used to being only half; half a sister, half-Indian, half-Irish . . . not as wholly Indian as their father, Govind, and not as wholly Irish as her mother, Maeve. Her skin was neither white nor brown; her hair neither black nor red. Only her eyes, her pale, flecked-brown eyes like the skins of almonds, were exactly the same as her father’s eyes and exactly the same as Marvinder’s. But she would not know this yet. She didn’t look in mirrors – at least not to assess herself. Her mirror was other people, and she saw herself the way they saw her.

‘Are you ready?’ Maeve asked. There was no enthusiasm in her voice.

Jaspal, Marvinder and Maeve’s young sister, Kathleen, had been lolling in front of the fire, engrossed in comics. Marvinder got up immediately, and pulled down her coat from the door, and Kathleen went over to her little niece, to coax her into staying. Jaspal rudely ignored Maeve and went on reading.

‘Well, come on then,’ Maeve was impatient. ‘Get your coat on, Jaspal. We’ll miss the bus. Good grief, we only go once a fortnight and, after all, it is to see your own father.’ She almost spat out the word ‘father’ like a bitter pill.

‘Can I go see Dadda!’ wailed Beryl.

‘Yeah, take Beryl. I don’t want to go,’ Jaspal muttered.

‘Come on, bhai,’ urged Marvinder, and she chucked his coat at him.

He reacted angrily. ‘Look what you’ve done, you stupid idiot!’ he yelled, dragging his comic out from under the coat. ‘That’s my comic. You’ve gone and wrecked my comic!’

Marvinder looked pained. Jaspal never used to talk rudely to her. ‘It doesn’t looked wrecked to me,’ she retorted. ‘Here!’ She reached out to straighten it, but he whipped it away.

‘Leave off. It’s mine.’

‘I know it’s yours, silly! I was just going to smooth it out.’

Maeve ran over impatiently and snatched at the comic. ‘For God’s sake, Jaspal, will you stop messing around and come. We’re going to miss the bus, I tell you.’

There was a ripping sound.

Jaspal gave a bellow of fury. ‘Look what you’ve done! You’ve torn it . . . you . . .’ He looked as if he would fly at her, but Marvinder grabbed his arm.

‘Jaspal, no!’ She begged, ‘Just put on your coat and come.’ She picked up his grey worsted coat and firmly held it out for him.

Jaspal snorted angrily and broke into a stream of Punjabi, which he knew infuriated Maeve. ‘Why should I do what that woman wants? She’s not my mother. She’s nothing but a thief and a harlot, stealing away our father. Now she thinks she can lord it over us. Well, she can’t. I don’t have to do anything she says.’

‘Oi, oi! You being rude again, you little devil?’ It was Mrs O’Grady appearing at the door. Her plump face was red with effort. She was panting heavily with having hauled two vast bundles of other people’s laundry up the long flight of stairs. ‘You needn’t think I don’t know what you’re saying, just because you speak in your gibberish.’ She dropped the washing and strode over to Jaspal with her hand raised. ‘You get your coat on immediately or you’ll get a clip round the ear.’ She hovered over him, threateningly. ‘And if I hear you’ve given Maeve any of your lip while out, Mr O’Grady will get his belt to you.’

That was no mean threat. One leg or no, Mr O’Grady was a powerful distributor of punishments, and even his strapping sons, Michael and Patrick, had to watch themselves when their father got mad.

Jaspal sullenly thrust his arms into the sleeves of the coat which Marvinder still held out for him, though when she tried to do up his buttons he pushed her away.

‘I’ll do it,’ he growled. ‘I’m not a baby.’

‘Huh, I’m not so sure about that,’ snapped Mrs O’Grady, lowering her hand. ‘Now get off with you,’ and she herded them to the landing, checking their hats and scarves and gloves and warning them about the chill out there.

If those who make up a family are like the spokes of a wheel, then Mrs O’Grady was both the hub and the outer rim. She held them all together; she fed them, nurtured them, washed and cooked for them and bullied them. She put up with her husband, with his drinking and temper and his fury at losing a leg in the war; she hustled her two boys, Patrick and Michael, making sure they got off to work every day – then taking half their wages at the end of the week, to store in the teapot which stood on the mantelpiece; and when Maeve had got pregnant by Govind – even though the man was a heathen and as brown as the River Thames, she insisted that the couple move into the household, taking the top-floor flat, which meant that the younger sister, Kathy, had to move down and sleep in the hall under the stairs.

In due course, when Beryl was born, it was Mrs O’Grady who coped, for Maeve was a reluctant mother, distraught at finding her freedom curtailed; and only a woman as mighty an Amazon as Mrs O’Grady could have endured the shock of finding out that Govind already had a wife and family back in India; only a woman with shoulders as broad as a continent could then take on his two refugee children, Jaspal and Marvinder, when they turned up out of the blue to find their father – a father who had got mixed up in black-marketeering and who was then sent to prison. She may have raged and grumbled and lashed out with her tongue, but she never complained. But kneeling in the darkness of the confessional, she had whispered to Father Macnally that she had prayed to the sweet Virgin not to send her any more children to look after – and especially, please – no more heathens.

‘Mum!’ Beryl wailed pathetically. She broke away from Kathleen’s arms and reached out for Maeve. ‘I want to see Dadda. Take me too!’

Mrs O’Grady snatched up her grandchild and held her firmly, ‘You stay with your Gran and your Aunty Kathleen, there’s a duck. You can go next time.’

‘We’ll see you later, Beryl,’ Maeve cooed at her child, trying to soften her voice and her face, before following Jaspal and Marvinder downstairs and out of the front door.

A sharp spring wind blew up Wandsworth High Road. It blew the scattered bus tickets into red, blue and yellow spirals and whirled them along the pavements. It made you hold on to your hat and clutch at your coat. It was the sort of wind which found its way into every crevice between neck and scarf, or wrist and glove. Even through the buttonholes. They bent their heads before it as they walked to the bus stop; and turned their backs on it, as they waited and waited for the red double-decker to come.

They were grateful to the wind. At least it gave them an excuse not to talk. Instead, they buried their reddened chins into their scarves and collars and gazed wistfully down the road, as if their very concentration could will the bus to come quicker.

And when it came, roaring to a stop in response to their outstretched hands, they always went clattering up the metal spiral steps onto the top deck. Maeve liked to smoke.

Jaspal and Marvinder would rush for the seats up at the very front above the driver’s head. They enjoyed the clear open view, and the feeling of being on top of the world. They could lean right forward and press their brows up against the glass.

But for all that, it was a gloomy journey which none of them relished. If only they could have got off at the river and spent the day in Battersea Park, or if, instead of changing buses at Hammersmith, they could have walked down to Shepherd’s Bush market and milled around the hustle and bustle of the stalls. Instead, they had to watch it all slide by and listen to the monotonous warnings of the conductor. ‘Hold very tight, please,’ as he tugged on the lower-deck bell string. ‘Ting, ting!’ It was one ting to stop and two tings to go.

At last they reached Ducane Road. The vast open playing fields of Latymer School seemed to gather up the winds and hurl them into their faces.

That final walk always seemed the longest. Maeve walked a little head, as if embarrassed by them, looking fixedly in front, never addressing any remarks to them, as if afraid people might think they were her children.

Two groups of people walked the same pavement, but managed to create a meaningful distance between each other.

There were those whose destination was Hammersmith Hospital, and with whom Maeve tried to merge for most of the walk. They were a generally cheerful lot, clutching bunches of newly-bought flowers from strategically-placed flower-sellers, or brown paper bags full of whatever fruit they could obtain with their ration coupons.

This group pretended not to see the other group, with whom, for a while, they shared the same pavement and the same direction. Their eyes looked through them as though they were ghosts, and there was a certain smugness, when this first group branched off and poured through the gates of the hospital in time for visiting hours.

The second group pretended not to notice or care. Their faces were grimmer, their pace more reluctant. Hardly anyone spoke, but concentrated on coaxing their children along, or simply fixing their focus on the next main gateway, to which they finally came. And when they walked through, they kept their eyes lowered to the ground. They never looked up at the grim fortress towers of His Majesty’s Prison, Wormwood Scrubs.

Here, Maeve, Jaspal and Marvinder joined a sizeable straggle of mostly women and children, gathering outside the large oval gate, waiting for the exact moment when they would be admitted. No matter how awful the weather, the gate was never opened even thirty seconds earlier than ordained.

Unlike hospital visitors, they weren’t allowed to take in flowers or fruit or packages of food. Each was frisked at the gate; handbags were opened and searched. They were made to feel that by visiting a prisoner, the visitor too was somehow guilty.

After further hanging about, they were all finally ushered into a large room, supervised by blank-faced warders, where, waiting for them at a series of tables, were the prisoners, their eyes eagerly scanning the faces as they came in.

Marvinder saw her father.

He was thinner these days. Perhaps it was the way they cropped his hair very close to the head; it seemed to emphasise his gaunt face; it made his cheeks look more hollow. His skin was blanched as if deprived of sunlight.

Lately, he had become withdrawn. Marvinder wondered whether it was to do with the killing of Mahatma Gandhi. When they broke the news to him a couple of months back, he looked as if he were going to faint.

‘Was he a very important man, Pa?’ she had asked, when he had collapsed into his chair and thrust his head down on the table between his arms.

‘Who can forgive me?’ was all her father had been able to choke, as if he had been the assassin.

‘When he was a student your father admired Mahatma Gandhi; worshipped him like a saint,’ Jhoti had explained inside her daughter’s head. ‘He travelled miles to attend his gatherings, and then came back to the village with such stories. He would tell us that the British were going to leave, and that India would become independent; how this little, half-starved man, with only a piece of cloth round his middle, was standing up to the might of the British Empire. The whole village would gather round to listen. Your father was such an important person in those days. But now . . . who would have thought . . .’

Marvinder waved a timid greeting. Her father raised a hand in acknowledgement. He stood up, but looked past her. He looked past Maeve too. It was Jaspal on whom he feasted his eyes. His gaze seemed to plead for understanding and forgiveness. ‘Can’t we be friends?’

But Jaspal lowered his eyes with embarrassment. It had been easy to love his father when he thought he was a hero. When they had lived in India, in their little Punjabi village, Jaspal, who had never known his father, grew up looking at the proud, flower-draped photograph, which had been taken when Govind graduated from Amritsar University. His turbaned head, with sleek moustache and confident eyes, stared out with a faint look of surprise, as though marvelling that he, the son of a simple farmer, could rise to such heights.

Govind had come to England to study, encouraged by Harold Chadwick, his English teacher back in India. He enrolled at London University to do a degree in law. He was urged to be someone; do something for his newly-independent country. But all these plans had been interrupted by the war. He had joined up along with all his fellow students and fought in Europe and North Africa.

So where was that hero now? Where was the soldier-scholar, whose garlanded image Jaspal had grown up with and admired every day? Where was the Sikh warrior, who had gone into the British army to help fight against the Nazis? When the war ended, and Govind didn’t come home, they never for a moment disbelieved his letters, which told them first, that he had been wounded and was undergoing treatment, and then, that he was trying to earn enough money in Britain, so that he could return to India and set up a business.

Jaspal remembered how his mother, Jhoti, had fretted. ‘Why doesn’t he come home? We need him here. We need him as a father to protect his family. Doesn’t he know what is happening here?’

Surely Govind must have heard. The whole world knew that Britain had finally granted India the right to independence. But even before the British left, the troubles began. When part of India split away to become Pakistan, in the vast interchange of populations from one country to another, thousands were slaughtered. And in the Punjab, the Sikhs, who were neither Hindu nor Muslim, fought for their own identity – and some, for their own homeland too. How could Govind not know? Why did he not return to protect his family?

But what did Govind, their father, know of all this? It was ten years since he had left India, and it was as though he had never belonged there, never had a family there, no parents, brothers or sisters, no wife and two young children.

By the time he married Maeve O’Grady, he was another person altogether. He never talked about India to her; never told her about his other wife and children; and the more time went by, the less reason he saw to confess – especially after Beryl was born.

Then Jaspal and Marvinder turned up on his doorstep in England and, like a thrust of the wheel, his whole world revolved and his past life confronted him.

At first, Jaspal couldn’t believe this was his father. He had no beard, no turban. He wasn’t a scholar or a warrior, or anyone he could be proud of. Worst of all, Govind had betrayed them all; Jaspal, Marvinder and their mother, Jhoti.

Then they found out he was part of a criminal gang.

Bitterly, all Jaspal could hear was Mr O’Grady’s words ringing in his ears, ‘He’s nothing but a spiv; a black-marketeer; a petty crook.’

‘But he did save a man from the fire,’ Jaspal had pleaded. ‘The newspapers said he was a hero.’

‘Just as well,’ Mr O’Grady had snorted. ‘Otherwise he would have gone to the gallows for murder.’

For that heroic act, they hoped his other crimes would be overlooked, but it was not to be. The wheels of justice turned, and Govind was convicted for black-marketeering.

‘It’s good that Ma never knew what Pa did in England,’ Marvinder had whispered when their father was taken off to prison.

Govind held out his hands greedily, eager to clasp each one. Jaspal avoided his father’s gaze and pulled away from Govind’s grip as soon as he could. He flopped down in a chair, and turned it sideways on, looking deliberately bored.

Marvinder pulled her chair closer, but sat with lowered eyes. No matter what Govind had done, she couldn’t hate him, and she wished she had magic powers, so that she could free him from his prison. She often imagined how she would help him to escape and they would all run away back to India. Then they would find her mother, Jhoti, and everything would be all right.

‘How are you doing for money?’ Govind asked Maeve. They sat facing each other across the table. They didn’t touch; each kept their hands clasped together in front of them.

‘We’re managing,’ she replied sullenly. ‘I’ve got a job at Franklands Engineering. Gives me about fifteen bob a week; a pound, with overtime. Between Mum, Dad and the boys, we get by. We get Family Allowance too. They’ve agreed to give it for Jaspal and Marvinder, as well as for Beryl, and I’ve got ration books for them now. That friend of yours, Mr Chadwick, he found out about it all for us.’

‘That’s good.’ Govind sighed with relief. ‘How’s Beryl?’

‘She’s fine.’ Maeve fingered her wedding ring so that she didn’t have to look at her husband. ‘The children bring home these American food parcels from school. That helps,’ she murmured.

Govind waited for more news of their child, but Maeve fell silent and went on twisting her ring round and round.

‘I’ve got something for her.’ Govind reached down to a brown paper bag at his feet and pulled out a stuffed elephant.

‘That’s nice!’ Marvinder exclaimed with enthusiasm. It was patchworked together from different bits of material and stuffed. ‘Isn’t it nice, Maeve?’

‘I made it in the workshops,’ Govind said with weary pride. ‘I’m halfway through a camel. It’ll be ready next time you come. But I hope Beryl will like the elephant.’ He stood it on the table for them to admire.

‘It’s lovely, isn’t it, Maeve!’ Marvinder persisted. ‘Course Beryl will like it, won’t she?’

Maeve nodded, giving it a cursory glance, but made no move to examine it. Marvinder picked it up. ‘Look, bhai! ’ She showed the elephant to Jaspal. ‘Isn’t Pa clever to make this?’

‘Why did you make an elephant?’ queried Jaspal in a cold voice. ‘They don’t have elephants here or camels, except in zoos. You should have made a dog or a cat.’

‘Shall I make you a dog or a cat?’ asked Govind, trying to please.

Jaspal almost snorted with derision. ‘Stuffed toys are for babies! Billy’s father makes boats. He sails them in the park. He might let me make one,’ added Jaspal cruelly.

‘Who’s Billy?’ asked Govind quietly.

‘My best friend,’ said Jaspal. ‘His dad might give me a job later in his workshop. He said I had all the makings of a carpenter. I can still remember everything old uncle taught me back in India.’

‘Who was your best friend in India? You used to write to me about him. The son of that Muslim tailor, Khan, wasn’t he?’

‘Nazakhat,’ said Marvinder, when she saw Jaspal purse his lips tightly. ‘Nazakhat and the Khans saved our lives. Without their help we would have been killed . . .’ Her voice trembled as she remembered.

‘Perhaps you should never have left Deri,’ murmured Govind. ‘Perhaps you should have stayed and taken your chances. Your friends, the Khans may have continued to protect you.’

‘They’re all dead,’ stated Jaspal, flatly.

‘Oh, Jaspal, how can you say that?’ protested Marvinder. ‘We don’t know anything for sure.’

‘I’ve read all about it in the papers. Millions have died, especially in the Punjab. Nazakhat must be dead. Ma, too. We would be dead if we’d stayed.’ His voice was cold and emotionless. There was an uncomfortable pause. Then Govind changed the subject. ‘Maeve says you’re going to be sitting the eleven-plus. You could go to grammar school and maybe to university.’ Govind leaned forward earnestly. ‘You could do what I was meant to do, if you study hard.’

‘Huh!’ Jaspal snorted again and turned away, no longer interested in communicating with his father.

‘What do you want to go putting ideas into his head like that for?’ Maeve reproached him in a shrill voice. ‘We’re short enough of money as it is, what with you in here. The sooner he’s out earning, the better – and her!’ She indicated Marvinder. ‘That Dr Silbermann’s giving her ideas too, what with all this violin playing. I don’t think it’s healthy, all the time she spends down there.’

Govind looked at his daughter and sighed. In India, he would have been negotiating her dowry and arranging a marriage for her. She was exactly the same as Jhoti, her mother, when he married her.

‘Perhaps when I get out, I’ll take Marvi back to India and get her marriage arranged. That would be the best.’ He spoke with the sudden enthusiasm of a good idea.

‘No, Pa, no!’ Marvinder stared at her father in horror.

‘I thought you wanted to go back.’ He frowned.

‘I do, I do. But I want to go back with you and Jaspal. I want to go home. I want to find out about Ma. I don’t want to get married. No one here gets married so young.’ Tears welled up in her eyes at the thought.

Maeve shrugged. ‘Come off it, Govind, she’s only thirteen, and she hasn’t even started her monthlies. I was thinking maybe she could do a paper round.’

‘I’d like a horse,’ said Jhoti inside Marvinder’s head. ‘A bridegroom’s horse, all decorated and ribboned.’

‘Could you make a horse?’ Marvinder asked her father, wiping her eyes on her sleeve. ‘I’d like a horse.’

‘Of course,’ replied Govind. ‘I’ll make one for you by the next time you come. It doesn’t take long.’