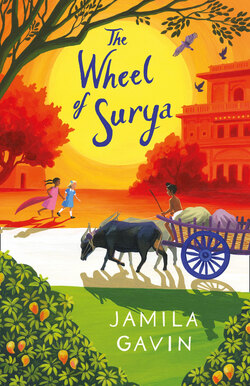

Читать книгу The Wheel of Surya - Jamila Gavin - Страница 14

ОглавлениеSEVEN

The Lake

Beyond the church, through a deeply shaded area of mango trees, crumbling slowly away under monsoon rain and relentless sun, invaded by the predatory embrace of weeds and vines and twisting roots of ivy, was the rajah’s palace. It was Marvinder who had first told Edith about it.

‘Doesn’t look much like a palace to me,’ Edith complained. She thought all palaces would be like the ones in her book of fairy tales; palaces with tall narrow turrets, marble domes and slanting roofs of gold with arrow slitted windows. But when they clambered through the tangle of vegetation and reached the vast sweep of grey stone verandah, she was impressed.

The building rose like a huge mouldering wedding cake, supported on great, fluted stone pillars and rising tier upon tier, terrace upon terrace until finally it culminated in a flat roof, fifty, eighty, a hundred feet up, hemmed in by stone balustrades and fierce parapets.

Edith fell silent. She was overawed, even afraid. It was so wild, so defiant. If silk-turbanned rajahs and bejewelled queens had ever looked out of those blank windows, or stood on the roofs to watch the sun go down, all trace of them had been smothered. Wherever there was a chink, a crack, a space between pillar and roof, step and verandah, wall and ceiling, a plant, a tendril, a cluster of grasses had seeded itself; long trailing weeds and brilliant flowers, cascaded precipitously; saplings reached out like new-born foals on long dangly legs, with twigs and leaves sprouting and spreading out and out into unimpeded space.

By day, pigeons and sparrows and kites and crows flew in and out of the rooms and roofs; bees, hornets and wasps built their own vast palaces of honey which hung like huge nets from the alcoves. But by night, the palace became the domain of bats and owls, stray dogs and roaming hyenas. Snakes slithered out across the cool stone and a myriad of brilliant insects swarmed in and out of their hidden kingdoms.

At first, Edith hadn’t wanted to stay long. It frightened her, and she had turned haughtily, remarking that it wasn’t her idea of a palace. But that was years ago. Now she was older, nearly ten. She had been at boarding school for almost two years and had become hardened.

The absence from home was long. Six months without a break, without seeing her mother and father. She blamed the twins. If it hadn’t been for them, the war wouldn’t have broken out in Europe, then they would have all gone back to England; they would have lived together in a house and gone to day schools. But the day war broke out was the day the snake nearly bit Ralph, and somehow she linked the two events with her despatch to boarding school. The twins required so much attention and hard work. Edith thought of them as leeches, sucking away at their mother. Even now, although they were six years old, she never saw her mother without a twin draped round her legs, or clinging to her neck, making demands, ensuring that there was no time for Edith.

At first she cried every night in her school dorm and wrote letters to her parents begging them to take her home. She thought that she would die of homesickness; thought that the lump of pain would never stop choking her, but then one morning, she woke up. The pain was gone, but it was as if a stone had replaced her heart and she had simply stopped feeling.

It was the same when she came home for the holidays. They met her off the train, her mother and father, each with a twin in hand. She felt hatred and stiffened when they kissed her. How annoying, then, that the twins adored her. Ralph and Grace followed her round everywhere, and called her Edie! And because Jaspal called his elder sister, Didi, as is the custom, the twins also called Marvinder, Didi. They loved the two sounds being so close. ‘Edie and Didi!’ they chanted, until it drove Edith mad.

One day, Edith remembered the palace and she whispered to Marvinder, ‘Let’s run away and hide from the twins. Let’s go to the palace.’

Marvinder was a little troubled at leaving the twins. They had been put partially in her charge, while Jhoti helped Dora Chadwick prepare the house for a party that night, though Jhoti or Dora was always popping out to check that all was well.

‘Do you think we should?’ Marvinder asked. ‘We were supposed to keep an eye on the twins.’

‘We always have to look after the twins,’ wailed Edith. ‘I’m fed up. I want to play my own game. I want to go to the palace and play kings and queens. We can take dressing-up clothes. My mother has some lovely sarees and we can take cushions to sit on.’

‘How will we take it all there?’ asked Marvinder, getting swept away with the idea, despite herself.

‘We’ll take a bike. We’ll take Arjun’s bike. We’ll put the cushions and sarees in the front basket. I’ll cycle. I’ve ridden his bike before, and you can ride to the palace on the back seat.’

‘What palace?’ demanded Ralph, whose sharp ears caught the last part of Edith’s sentence.

‘Mind your own business,’ retorted Edith rudely.

‘Can we play whatever it is you’re playing?’ demanded Grace looking very interested.

‘Yes, you can play, if you can find your own dressing-up things,’ declared Edith, with a sudden cunning flash of inspiration.

‘Come on, Ralph, Edie says we can play too!” squealed Grace, tugging her twin into the bungalow.

‘Quick, Marvi!’ hissed Edith. ‘You get Arjun’s bike, and I’ll get the sarees and cushions. Let’s get away before the twins come back.’

Edith flew into the house.

By the time the twins emerged with armfuls of drapes and dressing-up clothes, Edith and Marvinder were a wobbly speck in the distance.

Their high-pitched voices called out in dismay. ‘Edie! Didi! Wait for us!’ But Edith pedalled away with fierce determination. Only Marvinder, sitting side-saddle on the back seat, turned her head uneasily, to watch Ralph and Grace rushing up to the gate, waving frantically. Then she saw their arms drop to their sides and their bundles of dressing-up clothes tumble to the ground as she and Edith dwindled from sight.

‘Hey! Ralph!’ Jaspal’s head appeared, peering over the wall as if he were a giant. When the twins saw him, they shrieked with amusement and went rushing over.

‘How did you make yourself so tall?’ asked Grace.

Jaspal grinned mysteriously. ‘I ate magic beans and grew in the night.’

Ralph and Grace were already climbing the small tree which grew up against the wall, and soon they were high enough to look over the other side.

‘Jaspal’s standing on his buffalo!’ chortled Ralph, who saw him first.

‘Let me see, let me see!’ urged Grace, pushing herself up the branch.

Jaspal laughed. He was in charge of this buffalo and he loved her. He named her ‘Rani’. He always took her to the fields each morning where she spent the day pulling up water from the well to irrigate the fields; then after school, he would bring her back to let her cool off in the pond near the village.

‘Where’s Didi?’ he asked the twins.

‘They’ve gone without us,’ scowled Ralph. ‘They’ve gone somewhere to dress up.’

‘To a palace, Edith said they were going to a palace!’ insisted Grace.

‘That’s what she said, but she probably made it up. Edith makes up things all the time,’ muttered Ralph. There isn’t a real palace here.’

‘Oh yes there is,’ said Jaspal. ‘I know where there’s a big palace. It is Ranjit Singh’s old palace. He was a famous king of the Punjab, my grandfather told me. No one lives there now – except ghosts, they say!’

‘Where, Jaspal, where?’ they exclaimed with delighted terror. ‘Take us to it.’

‘If you ride on top of the buffalo, I’ll lead you across the fields. It’s quicker that way, and there’s the palace lake there where I can let Rani cool off. It’s full of fish. We could go fishing!’

‘Come on, let’s go!’ yelled Ralph enthusiastically.

‘Can we really ride Rani?’ begged Grace.

Jaspal nodded with delight. ‘Of course! Her back is broad enough for ten children!’ He reached up a hand. ‘Come, you can jump down from there. It’s easy.’

Jaspal helped the twins on to the wall, then bringing his buffalo close, till its great bulging sides leaned into the wall, he helped each twin to slide on to the beast’s back.

‘Eh, Jaspal!’ Jhoti called her son from the verandah. She had just glimpsed the buffalo carrying the two English children on its back. They looked like little golden gods, with their blond sun-bleached hair streaming in the wind, and their honey-coloured arms and legs contrasting starkly against the animal’s thick, dusty black skin.

‘Where are you going?’ she called.

Dora came out to look too. She knew she should order them back, but when she called out their names, and they looked round at her with such joy in their faces, all she could yell was, ‘Be careful, my darlings! And Jaspal, don’t be away too long, will you!’

Jaspal walked to the side, so upright and proud to be in charge, his hair tied up in a topknot, his legs, which emerged from beneath a pair of grubby white shorts, as thin and knobbly as the stick he was carrying to guide the buffalo. He waved and shouted, ‘Back soon!’

Jhoti and Dora stood for a long while gazing after the buffalo with the children plodding across the fields, before finally going back inside to continue laying the dining-table.

The palace looked even wilder than ever. Edith gave a shudder and almost wished they had after all brought the twins with them. It seemed so lonely and so quiet. She would have suggested going to get them, or changing their plan and doing something else, but Marvinder had already pulled out a saree and draped it round herself.

‘Now, I’m a queen!’ she cried strutting up the verandah steps.

She swept the glittering material round her. It was turquoise and gold and when she let it billow out as she ran up and down, she looked like a wonderful peacock. Suddenly, she paused briefly in a great dark doorway. ‘Let’s go inside!’ she said, and without waiting for an answer disappeared into the black chasm.

‘Marvinder!’ Edith rushed up the steps in a panic. ‘Don’t go away.’ She hesitated for a second in the doorway. She could see nothing inside but an impenetrable darkness.

‘Marvinder?’ Her voice had dropped to a whisper. There was no reply. She stepped a half step forward. ‘Marvi! Answer me!’ she demanded, hoarsely. She heard a stiffled giggle. Edith moved forward more boldly. She couldn’t see anything at first, and then slowly, her eyes began to adjust and she saw that trickles of green light revealed a huge empty room.

‘Marvinder!’ she called out loud. Her voice echoed, and there was a rush of wings as a disturbed pigeon flapped past her face and swooped through the door, making her scream.

‘Edith, come up here!’ Marvinder’s voice came from somewhere above her head.

Edith looked slowly round, and then she saw the opening in the far wall and the start of some stone steps. The steps were narrow and twisting with no rail to hold on to, and the treads were worn, as if thousands of feet had climbed up and down and up and down, gradually hollowing out the stone. She put one foot into the first indentation, then the next and the next, as steadily she climbed upwards.

A shock of brilliant daylight greeted her eyes at the top. She had emerged on to the first terrace. It was like stepping out on to the deck of a ship, for the whole palace seemed to be floating in a great green ocean of foliage which trembled and undulated all around.

‘Edith! Look at me!’ Marvi’s voice came from inside the enormous room which extended almost the full length of the terrace. Edith dashed in through the large rectangle of a door.

It was a wonderful room, which must once have been furnished with huge silken cushions, magnificent rugs, embroidered hangings, low, intricately-carved ebony tables on which stood brass lampstands and ivory boxes inlaid with precious stones; a room whose walls must have been hung with the skins of tiger, leopard and cheetah and the antlers of deer decorating the doorways. A room fit for a king, a hunter, a proud ruler, a warrior, where princes and princesses rustled by in fabulous silken clothes and brilliant turbans; a room with space enough for eye-flashing dancers to whirl and stamp, and musicians with sitars and tamboura to hypnotise the night with passionate ragas, while tabla drums beat their audience into a frenzy.

Edith sensed it, though the room was stripped as bare as a rock. It was as though some strange spell had been cast over the palace; the carpets had been turned into dry, dead leaves, which tumbled lazily across the dusty, stone floors; the silken cushions had become lumps of stone; the only trophies on the walls were the lizards which streaked like lightning from one diagonal to another, only to stop suddenly, utterly motionless, as if playing some game of statues. And the kings and queens? The princes and princesses? Where had they gone? Had they turned into the shiny-backed beetles which scuttled in corners? Or the long-legged spiders which spun their own web of curtain across the windows? Or were they the ghosts the people whispered about, who emerged sometimes to reinhabit their chambers and walk the verandahs and terraces?

‘Look at me!’ said Marvinder softly. She sat at the far end of the room on a slightly raised stone dias. She sat cross-legged with her turquoise saree swirled all around her. The sunlight caught the silver and gold threads and made them glisten. She looked like a queen.

They began to play; almost silently, almost as if they, too, were under a spell. They laid out the cushions and draped themselves in sarees and veils; they moved around making royal gestures, and began to wander up and up through the palace, till finally they reached the roof.

At this height they were level with the tops of trees and looked out over the landscape around them. They felt like gods. There was the church and the graveyard; there was the long white road, running like a shimmering thread, on and on, past Marvinder’s village, on and on until it would have reached her mother’s home village, except that it disappeared over the horizon.

‘I can see my house!’ screamed Edith gleefully.

When they crossed the roof to look out over the other side, an avenue of sky ran between the great spreading boughs of eucalyptus and mango and neem trees; it took the eye all the way down to a shining lake which Edith never knew existed.

‘Look! Oh look!’

‘That is the rajah’s lake,’ said Marvinder. ‘It’s where he used to fish. My uncles go there often.’

The lake was surrounded by wild undergrowth, which made the waters look dark green. In the middle of the lake was a small island with a landing stage for mooring a boat, and a cupola, which jutted out like a stone umbrella under which a king might sit and fish through a hot afternoon.

Beyond the lake on the other side, the jungle had been kept at bay by the farmers, whose fields of wheat and mustard came right up to the boundary. Across one of these fields, Jaspal and his buffalo came into view carrying Ralph and Grace on its back.

Edith leapt up and down with excitement, screaming at them. ‘Ralph! Grace! Look! Over here! Oh, please look, you two!’

Marvinder, too, waved and yelled at the top of her voice. ‘Jaspal! Jaspal bhai! ’

But somehow the three of them didn’t seem to hear. Perhaps they were too intent on the boat. Jaspal helped Ralph and Grace to slide off the buffalo’s back and while the children ran their fingers over the battered, wooden sides of the boat, the buffalo ambled down to the water’s edge and immersed its great body in the mud and weeds.

The boat was already very close to the water so when a slight breeze ruffled the surface, the stern bobbed gently as tiny waves lapped around it. All it took was a push and it was afloat.

Edith and Marvinder watched, at first still waving and shouting in their efforts to get the children’s attention; then they fell silent mesmerised by the scene, which slowly unfolded like a piece of mime.

Ralph pointed to the island in the middle of the lake. Grace and Jaspal looked and nodded enthusiastically. Grace climbed into the boat and awkwardly crawled over the centre seats to the stern. She didn’t notice the loose planks or the holes in the sides. Ralph and Jaspal, still on land, put their hands to the prow and began to push. The boat wobbled and they could see Grace laughing. She put her hand to her mouth as if to stiffle anxious squeals.

The boys pushed and heaved, their arms extended to the full, out in front, their legs stretched behind as they put the full weight of their bodies into the push to get the boat away from the shore. At last, with a final heave, the boat slid away with the boys plunging into the water after it.

‘Oh, what fun! what fun!’ cried Edith, clapping her hands despite herself. ‘Look at them trying to get into the boat!’

The boys were both balanced on their tummies tipping and rocking as they pulled themselves aboard.

Marvinder didn’t speak.

Ralph found an oar and wriggled it out from under the seat. There seemed to be only one. He began to plunge it into the water. Meanwhile, Jaspal and Grace were using their hands to paddle the boat along.

Slowly, slowly, the boat began to drift further and further from the shore, whether by the exertions of the children or by a faint wind which caught the craft in its grip and tugged it out towards the centre of the lake.

The same wind suddenly sent a heap of dead leaves scurrying and rattling across the palace roof, and made the girls’ sarees billow out like sails. A flock of green parrots exploded into the sky with a wild screech. If only they could have leapt as easily into space from the parapets and flown down to the lake side. If only their sarees could have turned into wings and given them the power of flight. Instead, they stood, helpless and rooted.

It was like looking through the wrong end of a telescope. They saw the terror of the children as the boat began to fill with water. The children used their hands, frantically trying to scoop out the water. It was all so fast. Suddenly, the three children were up to their waists in the water, then their chests and then . . .

Edith was aware of a whimpering at her side. Marvinder’s fingers were clawing at her saree and she began to run, first away then back to the balustrade, then away, then back. Her whimpers became fierce screams, squeezed out of her body in short gasps. Then suddenly she was gone. Edith was hardly aware of it, for Edith just stood as if she had become one of the hard, grey, immobile palace stones; inactive; doomed, as these stones had been doomed to be a dumb, passive witness; to see but never to forget.

They looked so small, so insignificant, struggling there in the water. Their splashes were no bigger than a dog might make as it swims after a stick. Then suddenly, there was nothing except a blank expanse of water. No boat, no children.

Edith gave a deep sigh as if she were eternally weary. She turned away, and wrapping her saree tightly round her body wandered down like a sleepwalker to the grand chamber. Edith lay down on a cushion, her head on another and closed her eyes.

She slept.