Читать книгу Heaven is a Garden - Jan Johnsen - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

The Power of Place

Consult the genius of the place in all.

– Alexander Pope

A “heavenly” garden stills the world and holds you in its embrace. As you walk beneath leafy canopies or beside colorful flowers, wellbeing’s cloud envelops you and the stress of modern life slowly drops away. This garden has little to do with its size and everything to do with the emotional connection it makes with you. Your garden paradise can be as simple as a sundappled deck overlooking a small cascade or a homey terrace filled with planters and statuary. It can be an expanse of lawn bordered with exuberant flowers or a rustic scene of native plants and rock outcrops. Whatever your vision of a heavenly garden, it should fulfill your desire for a private space where you can enjoy Nature’s glory – where you can breathe and just be. Nowhere else do we feel as uplifted as when we are in a setting designed for relaxation and contemplation. Another way of describing such a place is “an unhurried garden.”

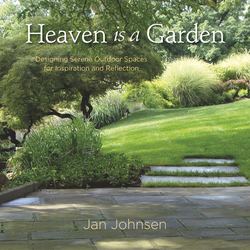

I love to create long, sweeping grass steps as these shown here. They are simple, gracious and relatively easy to install.

A heavenly, unhurried garden should be designed with three basic features in mind: simplicity, sanctuary and delight. Let me start with those three lovely words and show you what I mean.

Simplicity. When you have economy of form and line in a garden, the effect is calming and restful. A good example of this is a gently undulating plant bed. Its sweeping lines are relaxing and – though simple – can be as compelling as a rectilinear formal garden. “Less is more” is the rule here.

Sanctuary. Have you ever noticed that the most desirable place to sit outdoors is with your back to a wall or a tall hedge and looking at a lovely view? The security you feel in such a protected area is what I term “sanctuary.” It is the draw of a shaded walk, the call of a hidden gazebo or quiet niche. It is the lure of the sheltered corner.

A low, semi-circular retaining wall and a rock garden creates a sheltered feeling of sanctuary.

After I created this intimate corner, the property owner placed what we call a “pod” here. A perfect place to enjoy the garden!

Delight. Delight is anything that gladdens your heart: a hollowed out tree trunk, an interesting gate or an elegant stone lion. It is the most personal aspect of a heavenly outdoor space and can be found amidst a patio flush with planters or in a woodland garden dotted with foamflowers and ferns. You may thrill to a fire pit or bubbling fountain. Delight prompts you to savor your surroundings.

Delight in a garden can come in many forms. Multi-colored tulips, a deep blue gate flanked by boxwood, a rustic cascade or a line of the exuberant and hardy ‘Disco Belle Pink’ hibiscus (Hibiscus moscheutos ‘Disco Belle Pink’).

These three underlying ideas can be incorporated into any garden, no matter the style or setting. With the mantra of “simplicity, sanctuary and delight,” you can go ahead and take the first steps in creating a serenely beautiful landscape.

Finding the Power Spot – Drama in a Garden

When I begin a garden design, I always look first for the site’s “power spot.” This is a place that, for some reason, seems a little more interesting than anywhere else. A high section of lawn, a shaded corner or a half hidden rock can become the anointed power spot in your garden. You can strengthen or dilute a site’s character by highlighting its power spot.

In order to determine where it is, I walk around and consider the dominant features of the land. I stand quietly in different areas and feel the mood each one generates. Elevated locations, such as the top of a steep slope or an outlook, can elicit “a sensation, dwarfing yet ennobling,” writes Derek Clifford in The History of Garden Design. But a power spot doesn’t need to be grand; it can be a shaded area in a corner. This is a more subdued and familiar kind; it feels comfortable, like a favorite sweater.

An overlooked, rocky site can become a power spot. Place a statue, sculpture or light here.

If you are wondering where a power spot is on your property, please know that there is no one correct answer. It is your particular translation of the “genius of the place” that is important. The area that appeals to you the most will undoubtedly speak to others as well. You may see treasure in that slight rise or be attracted to a particular rock. My advice is, Go ahead and highlight it! Clear around it, illuminate it or make a small path that leads to it so friends can enjoy it. Once they ascend to the top of a cleared slope or sit on a swing beneath a great tree, they will understand why you call it your power spot.

Seven Ways to Highlight a Power Spot in a Garden

1. Name it! Naming something makes it special. Descriptive monikers are a fun way to mark areas of a garden. For example, you might call a massive tree that stands solitary in a field The Lonesome Oak. A promontory with a vista can become Lookout Point and a Japanese landscape featuring a statue might be referred to as The Buddha Garden.

The presence of a statue can help in naming a garden.

2. Mark the spot. Place a sign, a marker or an art piece here to signify the area. It can be as elemental as an upright stone.

3. Place a bench here. Benches or rustic sitting rocks establish a power spot as a destination. The opportunity to sit on a bench always draws people. A view of a curved stone bench in the corner of a yard catching the morning sun is irresistible.

Inviting bench in a morning garden.

4. Make it easy to get to. A power spot must be accessible. Provide a path to the spot, even if it is only a strip of mowed grass or a small stepping stone walk, six feet long. If you build it, they will follow!

5. Add seasonal interest. The colors of the season add punch to a power spot. A simple splash of Coleus injects excitement in the summer and continues through the fall.

‘Sedona’ coleus adds a spot of seasonal color.

6. Add lighting. Outdoor lights or battery-powered candles in lanterns provide sparkle and add intrigue. They invite visitors to enjoy a garden at day’s end.

7. Maintain it. Fallen branches, litter or brushy overgrowth can take away from the enjoyment of your power spot. A little natural imperfection is fine, but try to keep the area fairly free of debris.

The Draw of a High Point

A lookout is one of the most exciting areas in a landscape. The top of a hill, a rock or any other kind of high point satisfies our instinctive desire for a prospect, where we can view our surroundings. The higher the promontory, the better the view and the more connected we feel to the overall scene. This is what makes a high point so universally appealing. The gazebo shown at left was placed on a high point for that reason.

A lookout in the landscape draws people to it. I placed this custom-designed gazebo on a high point so people could look down on the garden below.

Thomas Jefferson knew about the power of a high vantage point. He purposely built his famous home, Monticello, upon a lofty summit in Virginia and wrote eloquently about enjoying the view. In a 1786 letter to Maria Cosway, he wrote that from his perch he could look down “into the workhouse of nature, to see her clouds, hail, snow, rain, thunder, all fabricated at our feet!” Indeed, given a choice between sitting on a low portion of a lawn or a place farther up, most of us will invariably choose to sit uphill. Perhaps it is an inborn instinct that we all have.

I often enhance an existing high point by creating a “destination” there. A small area at the top of a slope can be leveled and retained with a low wall, as shown in the photo at left, opposite page. Such a cut-and-fill approach can provide a place large enough for a gazebo, a bench or some comfortable chairs. The view of a garden seat on a hill acts as a compelling destination and visitors will look for a way to get there. Their prize, upon arrival, is a comfortable perch from which to enjoy the summit.

I created this enticing place to sit by levelling out a slope. The low wall in front retains the level area. I then chose some wonderful outdoor seats to add a bit of fun.

In the garden shown here, I painted two new benches a dark green to make them less obtrusive and to blend in with the scene.

A Graceful Way Up to a High Point

People often see a climb up a hill to a high point as an obstacle, but you can make it a lovely winding path or a mysterious rustic ascent. Both treatments transform an arduous journey into an enjoyable experience. In the case of very steep inclines, I rely on the illusion of scale and proportion to make it seem less intimidating. My motto is, “The higher the hill, the longer the steps,” because I have found that a long line of steps cutting across a slope reduces its perceived steepness. In the garden shown above, I installed three sets of long grass steps with split cobblestone risers across the face of a slope. The 12-foot-long steps counter the tallness of the hill and make it seem almost ceremonial. In fact, the formality of the grass steps so impressed my clients’ daughter that she chose to have her outdoor wedding ceremony here on these steps a year after they were installed.

Long grassed steps make a slope seem less steep. I used split Belgian Blocks as the risers here. I also made sure to alter the direction of the top run of steps to prevent a monotonous, overwhelming effect.

Curved grass steps create a lovely line in a garden. Here I made the steps exceptionally wide for a gracious effect.

I first saw steps with grassed treads in the Dumbarton Oaks estate in Washington, DC, 35 years ago. This garden is open to the public, and I heartily encourage you to visit there. The steps were designed by Beatrix Farrand in the early part of the 20th century and hark back to the grassed treads of English gardens. Since then, I have used them so often that grass steps have become a signature feature of my garden designs. I have found that they can be used in landscape styles ranging from contemporary to cottage. While the treads are always lawn, the risers of the steps can be fashioned from Belgian blocks, bluestone pavers set upright, thin granite edging or Corten steel.

Beatrix Farrand, Landscape Gardener

Beatrix Farrand, 1872-1959, was America’s first female landscape architect. She was responsible for designing the grounds of Princeton, Yale and many estate gardens, and assisted in plantings at the White House. Her masterpiece was Dumbarton Oaks, in the Georgetown section of Washington, DC.

Farrand grew up when there were no schools of landscape architecture, so she apprenticed herself to Charles Sprague Sargent, founder of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum and made several tours of Europe’s great gardens. She had an intuitive eye for design and this skill, together with her horticultural knowledge, helped her build a thriving practice.

In 1921, Farrand was hired by Mildred and Robert Bliss to design the gardens of Dumbarton Oaks. Mrs. Bliss wanted a romantic garden and requested that all details in the seats, ornaments and gates have literary connections. The tenacre property is a series of separate outdoor areas connected by walkways. Long views are numerous because Farrand believed in offering beautiful vistas on which to gaze.

As a token of their gratitude, the Blisses placed a plaque dedicated to Beatrix in the garden. It is in Latin and reads:

“May kindly stars guide the dreams born beneath The spreading branches of Dumbarton Oaks. Dedicated to the friendship of Beatrix Farrand

And to successive generations of seekers after Truth.”

The elegance and versatility of grass steps enables them to be sweeping arcs or a contemporary rectilinear feature. The type of line you choose for your garden depends on your intent. Long gracious curves allow people to fan out in all directions while straight lines of steps channel visitors toward a desired route. Curving steps look good from all angles, but straight steps are best viewed from the front. The depth of your grass treads can also vary: the minimum depth is 18 inches, but they can be as deep as 42 inches. I sometimes slope the treads so that they become, in effect, a ramped stairway. This aids in drainage for the grass and requires fewer steps to ascend a hill. The important point to remember, however, is that deeper steps require lower risers for a comfortable ascent.

Using “Hide and Reveal” to Lead to a High Point

An ascent to a high point can be made more enticing when you use an ancient Japanese garden design technique known as miegakure or “hide and reveal.” It rests on the idea that hiding a full view of a space can make it seem larger than it is. It can also make an ascent seem less daunting. Thus, if you screen a section of steps, visitors are more likely to venture up to see what is out of sight.

I “hide and reveal” steps by angling sections of them within a long run. A bend in a series of steps makes the ascent seem less steep and heightens the air of mystery. A small landing at each bend is helpful and lets people enjoy a meditative pause. I also obscure the full view up a hill by placing a leafy plant strategically, using shadows to “hide” a portion of the steps or narrowing them near the top.

Of course, outdoor steps that are half hidden should be illuminated at night. You can place lights high up in overhead tree branches to provide a diffuse “moonlight” effect; this creates quite the romantic scene in the evening. Additionally, a decorative light fixture such as a stone lantern next to the steps acts as a striking garden feature as well as a safety beacon.

The ascent to a high point is a significant aspect of its power spot appeal. The walk up may be narrow, rocky steps, a gracious incline or a grand staircase. Whichever it is, it will certainly be a lovely part of the serene garden experience.

The ascent to a high point is a significant aspect of its “power spot” appeal. These are various steps I have created to draw people up to a high point. Each fits the setting.

The Elizabethan “Snail Mount”

If you relish the idea of having a high point in the garden but your land is relatively level, why not follow historic tradition and mold an artificial hill? The first known constructed “mountain” was the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Towering over the sun-baked plains of Mesopotamia, this eight-story-high complex of terraced gardens was sculpted from imported soil and meant to evoke the tree-covered mountains of a far-off country. A more modest idea – and one more suitable for today’s gardens – is a variation on the lovely Elizabethan “snail mount,” which was a popular outdoor feature in the 17th century.

In 1625, English philosopher Francis Bacon wrote in his “Essay of Gardens” about forming a high “mount” in the center of a landscape: “I wish also, in the very middle, a fair mount, with three ascents and alleys enough for four to walk abreast; which I would have to be perfect circles…; and the whole mount to be thirty foot high.”

Visitors would walk up a three-story grassy hill via a path spiraling around to the top. The walk would cut into the mound, making it look like a snail shell, thus the name “snail mount.” The gradual ascent, going round and round, was perfect for ladies in their stiff hoop skirts. Their climb was rewarded at the top with a view of the formal gardens below. A power spot indeed! I suspect that another reason for creating a snail mount may have come from the availability of excess soil that was generated from the creation of the water features and sunken gardens popular during this time.

A Quiet Power Spot

A shady spot and a secret path enhances a power spot.

The lookout reigns over a garden, but the shadowy niche nestles within its heart. This kind of quiet power spot is “a place to dream and linger in of a summer evening, green with perpetual verdure.” So wrote the American poet and author Hildegarde Hawthorne in The Lure of the Garden. Such a place becomes a sweet outdoor sanctuary, as in the seclusion experienced under a wisteria-covered arbor, beneath the canopy of a wide-spreading apple tree or beside a ferny grotto. Interestingly, a garden that contains both a bright open area and a muted, shady spot makes for the most appealing locale, as it blends two distinct atmospheres. Imagine, for example, sitting on a bench under the protective canopy of a tree and looking out onto an open sunny lawn.

This was a shady spot that I enhanced with a stepping stone path, ostrich ferns, and a rock bordered dry stream that serves as a seasonal drainage feature. Sustainable, functional and lovely – a quiet power spot indeed!

A Woodland “Folly”

Shady corners can become power spots if you enhance them in some way. You can do this simply by clearing brush away from around a large tree or placing an art piece in a forgotten corner or niche among plants. I was once asked to draw attention to a shady spot at the edge of a distant wooded hillside. It could be seen from the house and the property owner suggested I design a folly for this neglected area. A folly is a picturesque feature, an eye-catching decorative element. They were common in 18th century European landscapes and were often built in the form of Roman temples or ruins, placed atop a faraway hill on an estate or set in a wooded hollow.

Following this time-honored tradition, I set four cast stone columns in an arc in a leveled area of my client’s garden. I used four columns and four curved grass steps to define the front of the folly. In many traditions, the number 4 represents the Earth, and so groupings of four elements are considered very stable and grounding. I retained the hill behind with large rocks and planted low growing pachysandra around them. This evergreen ground cover plant forms a dark green backdrop behind the light colored columns, evoking a rustic elegance amidst wooded surroundings. A shady corner power spot, indeed!

Four cast stone columns help to “ground” the scene.

A Garden in Tune with the Four Directions

In this age of GPS navigation, the cardinal directions of North, South, East and West may seem nothing more than useful aspects of highway signs. But in ages past, the “Four Winds,” as the directions were called, were an important consideration when laying out buildings, towns and gardens. For example, the main shopping road of ancient Roman towns was called the cardo, or heart, and always ran in a north/south direction. This tenet of town planning can still be seen in New York’s Fifth Avenue and other prominent avenues of older cities.

Using the Qualities of North, South, East and West

Each of the cardinal directions can be thought of as having its own distinct qualities, based on their solar and geomagnetic characteristics. In fact, many cultures saw them as having particular personalities. North is solid and quiet while South is celebratory and expansive. East is fruitful and promotes growth and West is social. If you know the characteristics of each direction you can knowledgeably locate a bench, house or plant bed.

The Four Directions in Brief

| North. | The direction of wisdom and contemplation. A site on the north side is the best location for an artful viewing garden. |

| East. | The direction of growth and rejuvenation. Vegetable gardens prosper here. Thoughtful reveries are best done facing east. |

| South. | Celebratory and vibrant. The south side of a home is the natural place for an open lawn and flower gardens. |

| West. | The direction of expression and sharing. A west-facing patio shaded by trees is best for gatherings with others. |

North – The Direction of Earthy Contemplation

North is the direction of all things that relate to the earth. It is associated with quiet contemplation and meditative sculpture gardens. The north side of a house is the natural place for large stones, specimen trees and any artful item that is to be admired quietly. We look to the north for “grounding.”

Why is this? In the early 1990s, scientists discovered that our brains contained a biomineral called magnetite. This highly magnetic form of iron oxide is similar to the magnetite naturally found in rocks. Sailors and ancient seafarers called it a lodestone; they would rub magnetite-laden rocks on metal needles to magnetize them. This was the genesis of the directional compass where the needles always point north. The magnetite in our brain is like our personal lodestone and may make us respond to the subtle magnetic pull of north. Perhaps this is why some feng shui practitioners advise us to sleep with our head pointing north!

I placed these granite steles in this garden on the north side of a house. They act as a focal point from a large foyer window.

Knowing that stone of any sort befits the north side of a house, I designed a quiet garden of stone and grasses for a contemporary home with a large, north-facing window. The floor to ceiling window offered a long, narrow view and reminded me of a Japanese alcove, where a flower arrangement or art piece is displayed.

I placed five rough steles, or upright stones, amidst soft, ornamental grasses in a plant bed at the far end of a long view (photo at left). The bed is edged by thin bluestone pavers and sits beyond a field of smooth, tawny colored concrete slabs and gray crushed stone. The contrast of the stone, concrete and feathery grasses provides an interesting textural counterpoint. The stones are particularly stunning at night when underground “well lights” dramatically up-light each one. The diffuse light spills over onto the surrounding grasses, forming an ethereal sight.

Several varieties of grasses are planted here. The feathery dwarf fountain grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides ‘Hameln’) and maiden grass (Miscanthus sinensis gracillimus) are wonderful companions to the short but vibrant ‘Elijah Blue’ fescue (Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’).

The soft blades of ‘Elijah Blue’ blue fescue look great next to a native glacial rock outcrop.

An important pointer for North gardens is to remember that shadows fall on the north side of a building. This can cast an unappealing gloom on a scene. Therefore, I located this garden about 20 feet out from the building – beyond the reach of the long shadows of winter. The resulting long view also adds drama and depth to the scene. A wonderful bonus for north-facing gardens is that at midday the sun is always behind you, which ensures that “nature’s spotlight” shines on the object but never gets in your eyes.

A viewing garden for the north side of a house, far out of reach of winter shadows.

A bench catches the gentle morning sun coming from the east. The ‘Neon Lights’ foam-flowers (Tiarella ‘Neon Lights’) that bloom in spring like it too.

East, the Auspicious Direction

East, the home of the early morning sun, is considered by many cultures to be the auspicious cardinal direction. Wise gardeners site their vegetables plots facing east because morning light provides optimal plant growth. Yoga practitioners face east when performing morning Salute to the Sun exercises to bask in the sun’s enlivening eastern rays. Designers of Gothic cathedrals sited them so congregants face east for prayers. And many libraries of old were designed so that the majority of their windows faced east.

We know east is associated with morning sunlight, but why do historic traditions also connect it with intellectual and spiritual pursuits? It may have to do with the effect of direction on our brain. Neuroscientist Dr. Tony Nader asserts that when we face east the firing patterns of the neurons in our brain’s thalamus are more coherent than when we face south or west. Could it be that we think more clearly facing east? Vastu, the ancient Indian system concerned with the design of the physical environment, suggests that students should face east when studying, for better concentration and sharper memory.

A hammock can encourage daydreaming, especially when it faces the east.

Knowledgeable garden designers, aware that an eastern outlook may enhance mental acuity, locate benches so that they face that direction. Ideally, you might encourage better daydreaming by hanging a hammock to catch the rays of the eastern sun. And if the hammock’s eastern orientation is coupled with a stand of trees to the west, then it is also shaded from the hot afternoon sun.

Morning sun streams through this gate, lighting up the dappled willow (Salix integra Hakuro-nishiki) that is planted just beyond it.

Always Follow the Light. There is nothing quite as pleasing as morning light shining through an east-facing garden gate. As we enter we see the brightness beckoning to us beyond the portal. The idea of the sun being in front of us, drawing us in, is similar to the “moth theory” of the 20th-century Miami Beach hotel architect Morris Lapidus, who noted that people, like moths, are attracted to light. This reasoning may be the basis of the “law of orientation” in Indian Vastu (like Chinese feng shui) which recommends that front doors, town entrances and garden gates all face east. In fact, the word orientation means towards the Orient, or towards the east.

An east-facing gate directs the view within.

An east-facing gate directs the morning light to highlight whatever is near the entrance. I used this to great effect when I designed this tall gate and stone columns. The 6-foot high arched gate, flanked on both sides by tall pillars, faces east; in the morning, the sun’s rays travel through it, spotlighting a golden thread leaf False Cypress tree (Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Filifera Aurea’). The lighting effect is enticing.

South - The Direction of Celebration and Flowers

South is the home of the midday sun and, according to feng shui principles, is the direction that resonates with radiance and light. The south part of a property is the natural place for an open field, a large lawn or a flower garden. It is a good spot for celebrations and can feature strong colors such as red and purple in brightly colored banners or foliage. A border of hot colors – yellow, orange, red – also looks wonderful in a south-facing garden.

The south side of a building or property is also well suited for anything to do with light or fire. It is direction of the fire element in feng shui; therefore, a garden torch, light fixture, fire pit or barbeque is at home here. Interestingly, Vastu considers land that is elevated in the south and southwest to be the kind of terrain that bestows prosperity.

An open south-facing area features sun–loving Knock Out® roses, ornamental grasses and Sargent’s juniper (Juniperus chinensis var. sargentii). The south part of a property is the natural place for celebrations and flower gardens.

The South Lawn of the White House uses the qualities of the south perfectly. The expansive lawn is situated south of the President’s Residence and is used for official outdoor events like the state arrival ceremony and the annual egg-rolling contest, as well as informal barbecues. Thomas Jefferson graded the South Lawn and built mounds on either side of it, which direct a visitor’s view down a long south-facing axis.

West is the direction for outdoor gatherings at the end of a day. I designed this west-facing patio to enjoy the view and the late afternoon.

West - The Direction of “Name and Fame”

West is the direction of the setting sun and is associated with the end of the day and fellowship. High-canopied trees that lightly shade the west side of a house create the sweetest place to linger at the end of the day. In Vastu, the west is where “name and fame are made” – in other words, where we share time with friends. A “sunset terrace” basking in the long orange-red rays of the setting sun is the best place for socializing.

Water is also associated with west. The trickling water from a fountain cools the atmosphere on a sunny west-facing patio. The photo at right shows a fountain I designed that features shows a series of dramatic fountainheads along a western stone wall directing streams of water into a raised stone basin.

The colors that look especially vibrant in the west are rich reds and dark orange.

Water features are well suited for west-facing sites.

Follow “The Way of the Sun.” West is the direction of endings, so it makes sense that garden walks proceed in a “sunwise” or clockwise direction. Visitors travel a garden path from east to west, following the sun’s path in the sky. This is akin to the Hindu practice of circumambulation, where they circle special places in a clockwise direction. The reason for this circular walk has been attributed to symbolic causes, but I surmise that it may be due to the flow of geomagnetic forces. Just as an electrical generator works with a rotating coil to create a magnetic field, it may be that people walking in a circular motion intensifies the geomagnetic energy field within that space.

I laid out this stepped garden path so that it curves out of sight and invites you to walk toward the sunlight.

A loop path allows people to walk the perimeter of a garden, looking inward from different viewpoints (photo, left). You can place different garden elements along this encircling path, creating places where people might pause. The stopping points lead people from one destination point to the next, bringing them back to where they began. The walk may be paved, gravel, grassed or mulched – or a combination of all.

“Pooling and Channeling”

In order to encourage people to pause on a loop path or any walk through a landscape, I use a design technique called “pooling and channeling.” It is based on the idea that people move through a space in the same way that water flows: water moves rapidly through a narrow, straight channel but slows down when it enters into a larger, wider pool. Similarly, people tend to pause when they arrive in an open area. So, to encourage people to slow down, make a larger area along a walk or where two narrow paths meet. People will instinctively stop here.

A Focus on Place

Native plants are the highest expression of a place.

The highest expression of “place” comes from honoring the natural environs of a region, taking a cue from natural scenes and using native rocks and plants. This should be the basis of any garden. Wherever you live – in the moist Northwest, the southern high desert, the Mediterranean Pacific coast or the lush South – I encourage you to incorporate native plants in your garden design. For example, if you live in the Northeast of the United States, observe the glory of the eastern woodlands. If you live in hot, dry Southern California, then succulents, agaves and cacti may be your theme. Swaths of native flowers, shrubs and grasses provide an entrancing vision that encompasses the beauty of shifting seasons and feeds and houses the ecosystem’s birds, bees and more. In addition, local stones and plant material “resonate” with their environment, lending a harmonious atmosphere to a garden. For all these reasons, try to use native or local resources whenever you can.

Melding local stones with existing vegetation enriches a garden and its connection to “place”.

Garden Metaphors

This shady dry stream suggests a river and catches stormwater when it rains heavily. Every year we plant annual flowers among the hostas, oakleaf hydrangeas and Japanese painted fern to make it colorfully eye-catching.

A garden metaphor is what I call any landscape feature that recreates a scene of natural beauty in a smaller scale. This can include a dry stone stream to suggest a river, a small earth mound to represent a mountain, or a grouping of trees to evoke a forest.

The ancient Japanese garden makers elevated recreating natural scenes to a high art. Their honored 11th-century manual on garden making, Sakuteiki, says that “you should design each part of the garden tastefully, recalling your memories of how nature presented itself for each feature…Think over the famous places of scenic beauty throughout the land, and design your garden with the mood of harmony, modeling after the general air of such places.”

My favorite garden metaphor is a dry stream. It connotes a babbling brook but, for the most part, contains no water. I was first introduced to dry streams when I lived in Kyoto, the locale of most of Japan’s famous gardens. I fell in love with their versatility and I use them often in my landscapes. I create a dry stream by lining a curving trench with rocks, buried halfway into the earth. The trench is filled with gravel and topped with a thin layer of smooth, rounded stones. Dry streams can be a prominent and beautiful feature in the garden while effectively dealing with seasonal wetness – you can incorporate subsurface pipes and sump pumps beneath their beautiful exterior to help out with surface drainage.

Plantings for a Dry Stream

I created a dry stream in my small backyard. It adds a serene touch and looks great studded with a variety of plants. Because the dry stream forms a primary view from the house, I tried to follow the Japanese garden rule in planting it up: approximately 30 percent of the plants are deciduous and 70 percent are evergreen. The abundance of evergreen plants keeps the stream from looking desolate in the winter.

I chose mostly low maintenance plants that tolerate partial shade. The list includes Japanese garden juniper (Juniperus procumbens ‘nana’), ‘Ice Dance’ sedge (Carex ‘Ice Dance’), Golden Sedge (Carex oshimensis ‘Evergold’), Siberian iris ‘Caesar’s Brother’ (Iris sibirica ‘Caesar’s Brother’), hemlock trees (Tsuga canadensis), arborvitae trees (Thuja occidentalis ‘Emerald’) and dwarf fountain grass (Pennistum alopecuroides ‘Hameln’). For summer color, I plant the wonderful, drought tolerant, purple annual strawflower, Globe Amaranth ‘Buddy’ (Gomphrena globosa ‘Buddy’). By the way, most of these plants are deer resistant!

I love my backyard dry stream. It adds garden interest to a small space and I feel at peace when I look upon it.

Fencing an Outdoor Space: The Inner Sanctum

A fence or screen transforms an ordinary outdoor space into a personal area where you can enjoy the outdoors undisturbed. A beautiful fence can define a garden, add a sense of privacy and make it seem like a “place apart.” The psychological buffer it provides satisfies our instinctive desire for security and, if designed correctly, increases the allure of an outdoor patio or garden.

This distinctive gate was fashioned from a salvaged window grill

Our ancestors would often enclose places of natural beauty such as a gurgling spring or forest clearing with a rudimentary enclosure. This provided needed protection from enemies and created a special place to relax and enjoy shade, refreshment and camaraderie. You can do the same, but make sure to place a fence far enough away from a sitting area so you don’t feel penned in. Soften the fence’s presence and take care to place the gate so that it does not interrupt the flow within the space. And lastly, choose the layout of the fence carefully.

The “Insulation” of a Wall

Walls create the outdoor sanctuary that we crave, offering an extra layer of insulation to a garden. They are the bones of a garden, dividing and defining space and creating sheltered outdoor areas. A tall stone wall framing one side of an outdoor space can act as a magnet. Place a few chairs in front of such a wall and arrange a collection of colorful planters and you have a delightful area to enjoy with friends.

I designed this patio to be partially enclosed by a low wall to afford a feeling of protection.

These two stone walls retain a steep slope and, at the same time, make a great backdrop.

In the photo shown here, I added a lower stone wall in front of an existing stone wall, to retain a high hill. The lower wall is not too high and creates an inviting space more in proportion. I placed three long bluestone steps leading up to this raised terrace. The strong horizontal lines of the steps visually counterbalance the steepness of the hill.

I often partially enclose an outdoor area with a low sitting wall, no higher than 22 inches. It makes a space feel intimate yet is not confining. Both rectangular and curved patios can be partially bordered with a wall. I have found that walls with right angle corners accommodate large furniture arrangements and are well suited to formal or modern gardens. On the other hand, curved walls bordering free form patio spaces create an alluring line and add a more playful tone.

Low walls create interesting lines in a landscape and form inviting niches. This allows people to sit undisturbed and out of the way of people passing by.

In the garden shown below left, I deliberately created a 15-foot-long niche bordered by a 21-inch-high wall in which to place furniture. Niches are the ultimate example of an insulated space, providing a coziness that is often missing in large, expansive landscapes. The stone wall is uncapped because the modern vernacular calls for simple lines and a minimum of ornamental detail.

* * *

The Power of Place lies in the ways that our physical environment affects us so mysteriously. For this reason, the spirit of a place must always be considered first and foremost. But what about the impact of line and shape? This often-overlooked aspect of a garden can radically alter the quality of our experience within it. The next chapter considers the intangible gifts we receive when pathways, terraces, plant beds and more are created with knowing attention to line and shape. You will see that the discussion of lyrical lines, repetition and contrast seem to evoke music. So much so, that I am encouraged to refer to line and shape in a garden as “Music for the Eye.”